Romanticism

Although the publication of Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads in 1798 is often heralded as the formal start of Romanticism, the roots of the movement began earlier. The Enlightenment, or Age of Reason, had embraced the power of rational thought and the scientific method to advance society in an orderly fashion. Romanticism, however, heralded a more individual approach, often guided by strong emotions and some type of spiritual insight. According to Romantics, deeper understanding of the world was achieved through intuition and emotional connections, rather than reason. In literature, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was one of the early proponents of the Storm and Stress (Sturm und Drang ) period, which rejected the Enlightenment’s focus on reason in favor of strong emotions and the value of the individual. Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) is a classic Storm and Stress novel, with a protagonist driven by his extreme emotions. In politics, the revolutions of the time were driven by certain Enlightenment concepts that would be important to later Romanticism: in particular, the idea of natural rights, which was discussed by politicians, philosophers, and writers alike. John Locke asserted that human beings have the right to life, liberty, and property, and Francis Hutcheson posited the difference between alienable and unalienable rights. Thomas Jefferson used these ideas more or less directly in his writings. Rather than owing loyalty to a monarch, the Declaration of Independence (1776) asserts that human beings have rights from God and the laws of nature that cannot be taken away by an earthly ruler. The French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte (a fan of The Sorrows of Young Werther who claimed to have read the novel many times) also challenged established authority.

Romanticism, as practiced by Wordsworth, is a natural outgrowth of those revolutionary ways of thinking. If human rights are derived from “the laws of nature and of nature’s God” (Jefferson), then it makes sense that Wordsworth sees God’s presence in nature. In his poetry, nature represents truth, purity, and innocence, so the poet praises children and women as closer to God, because he sees them as closer to innocence. Wordsworth also highlights how the “other” revolution—namely, the industrial revolution—had begun to affect society in increasingly negative ways. Wordsworth contrasts the pollution of urban areas with pristine nature, characterizing modern urban life as a loss of connection to spiritual values.

Wordsworth, however, is only one of many voices in Romanticism. If Wordsworth saw women as childlike in their innocence, other writers disputed whether that was, in fact, accurate (or desirable). Women responded to the debate about the rights of man by discussing the rights of women, leading to works such as The Declaration of the Rights of Women (1791), by Olympe de Gouges, and A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), by Mary Wollstonecraft. If nature could be a source for inspired reflection in Wordsworth, it could also be dangerous. Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” which touches on the Romantic idea of poet as genius at the end, notes the thin line between genius and madness. Exceptional individuals as protagonists are the norm in Romanticism, in part from the (early) admiration for Napoleon Bonaparte. The admiration for Bonaparte, however, began to fade among many Romantic poets as he became a part of the monarchy and a more traditional figure of authority. One type of exceptional individual, the Romantic hero, has either rejected society or been rejected, and therefore is no longer constrained by society’s rules (with the reminder that a Romantic hero is not necessarily romantic, but rather a product of Romanticism). Romantic heroes tend to be self-centered and arrogant, but are capable of compassion and even self-sacrifice, in some cases. A Byronic hero is a subset of Romantic hero, named for the poet Byron, who was described as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” The distinction between the two types can get murky, since the Byronic hero is in some ways simply a bit more dangerous and alienated than the Romantic hero (in fact, characters such as Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Faust in Goethe’s Faust have been called both by various literary scholars). Byronic heroes are more likely to have some guilty secret in the past, or some unnamed crime that is never revealed, which drives the characters’ actions, and they are more likely to end tragically.

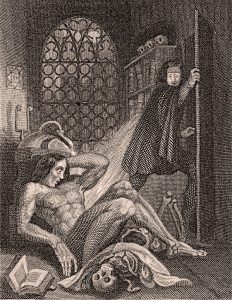

There were critiques of Romanticism even during the movement. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, she questions both Enlightenment views of science and Romanticism’s view of the hero. The first narrator, Robert Walton, fails miserably to advance scientific exploration in the Arctic, while risking the lives of others. Similarly, Victor Frankenstein’s self-absorbed behavior slowly destroys everyone around him. Victor’s passivity and silence become more and more criminal as the novel progresses. Mary Shelley began the novel while she and her future husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, were spending time with Byron, which makes her critical analysis even more intriguing.

The pinnacle of European Romanticism is Goethe’s Faust (Part One, 1806; Part Two 1832). Its title character embodies many, if not most, of Romanticism’s ideals: love of nature, emotional insights, individuality, and a never-ending search for knowledge and higher truth. Unlike Victor Frankenstein, Faust ultimately is successful in his search, although it comes at a cost. Romantics did not see a world without pain; they saw emotions, including pain, as a conduit to greater understanding. Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831) and Les Misérables (1862) address social injustice through the lens of Romanticism. The poetry of Mikhail Lermontov includes Byronic heroes and other outcasts from society, which also describes Aleksandr Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin (1832).

Literary movements are, of course, fluid and overlapping. Some scholars date the end of Romanticism to the early 1830s, while others extend Romanticism to as late as 1870. In British literature, Victorianism (1837-1901), which coincides with the reign of Queen Victoria, covers the transition from Romanticism to Realism; while poets such as Tennyson and Robert Browning are clearly descendants of Romanticism, their work contains realistic elements that do not technically fit into Romanticism. American Romanticism as a movement spanned roughly 1840-1865, and while it owed its initial existence to British Romanticism, it developed its own vision of the movement. American Transcendentalism was an early version of Romanticism in America. Influenced by Unitarianism and Hindu texts, Transcendentalism posited that human beings are fundamentally good; as such, they need no authority, but can be trusted to use their intuition and imagination to understand the world around them. In fact, Transcendentalists believed that many aspects of society served only to corrupt human beings, so nature offered an escape from society: both a temporary respite and an alternative way of living. Nature’s purity, it was thought, would restore mankind’s purity. Over time, American Romanticism took on a character quite different from English Romanticism. With writers like Walt Whitman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Emily Dickinson, and Herman Melville, American literature started coming into its own, inspired not only by its own revolutionary past, but also by a different version of nature found in the American wilderness. As both Transcendentalism and Romanticism were slowly replaced by Realism, ideas such as rugged individualism continued in the American consciousness. In many ways, Romanticism lives on in popular culture; elements of Romanticism continue into the present day in literature, film, and television.

Written by Laura Getty