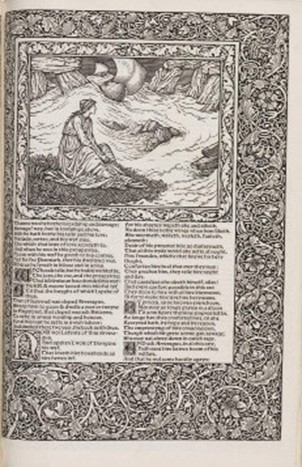

The Parliament of Birds and the Canterbury Tales

Author: Edward Burne-Jones

Source: Archive.org

License: Public Domain

Geoffrey Chaucer’s influence on later British literature is difficult to overstate. The most important English writer before Shakespeare (who re-wrote Chaucer’s version of the Troilus and Criseyde story), Chaucer introduced new words into English (such as “cosmos”), and his stories draw on a wealth of previous authors, especially Ovid and Boccaccio. Unlike Shakespeare, Chaucer’s writing is often translated, since Middle English is substantially different from even the Early Modern English of Shakespeare. The selections in this anthology are focused on a single theme: Chaucer’s revisionist, revolutionary approach to courtly love. Courtly love poetry often focuses on the male perspective exclusively; the female is the object to be obtained, and she usually is not given a voice (or, ultimately, a choice) in the matter. The Parliament of Birds (also called The Parliament of Fowles) gives the female a voice, if not necessarily a choice, while the General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales offers, among many other things, a satirical look at how courtly love can be misused: The Prioress and the Monk are only two examples. The Wife of Bath’s Tale and The Franklin’s Tale both offer fascinating alternatives to the regular courtly love scenario, while The Miller’s Tale is a mocking revision of the genre by the Miller, who is responding to the story of courtly love that had just been told by the Knight.

Written by Laura J. Getty

The Parlement of Fowles [The Parliament of Birds]

Geoffrey Chaucer, translated and edited by Gerard NeCastro

License: © Copyright, 2007, All Rights Reserved

The life so brief, the art so long in the learning, the attempt so hard, the conquest so sharp, the fearful joy that ever slips away so quickly—by all this I mean love, which so sorely astounds my feeling with its wondrous operation, that when I think upon it I scarce know whether I wake or sleep. For albeit I know not love myself; nor how he pays people their wage, yet I have very often chanced to read in books of his miracles and his cruel anger there, surely, I read he will ever be lord and sovereign, and his strokes will be so heavy I dare say nothing but, “God save such a lord!” I can say no more.

Somewhat for pleasure and somewhat for learning I am in the habit of reading books, as I have told you. But why speak I of all this? Not long ago I chanced to look at a book, written in antique letters, and there I read very diligently and eagerly through the long day, to learn a certain thing. For, as men say, out of old fields comes all this new corn from year to year; and, in good faith, out of old books comes all this new knowledge that men learn. But now to my theme in this matter: it so delighted me to read on, that the whole day seemed to me rather short. This book of which I speak was entitled Tully on the Dream of Scipio. It had seven chapters, on heaven and hell and earth, and the souls that live in those places; about which I will tell you the substance of Tully’s opinion, as briefly as I can.

First the book tells how, when Scipio had come to Africa, he met Masinissa, who clasped him in his arms for joy. Then it tells their conversation and all the joy that was between them until the day began to end; and then how Scipio’s beloved ancestor Africanus appeared to him that night in his sleep. Then it tells how Africanus showed him Carthage from a starry place, and disclosed to him all his good fortune to come, and said to him that any man, learned or unlettered, who loves the common profit and is virtuous shall go to a blessed place where is joy without end. Then Scipio asked whether people that die here have life and dwelling elsewhere; and Africanus said, “Yes, without doubt,” and added that our space of life in the present world, whatever way we follow, is just a kind of death, and righteous people, after they die, shall go to heaven.

And he showed him the Milky Way, and the earth here, so little in comparison with the hugeness of the heavens; and after that he showed him the nine spheres. And then he heard the melody that proceeds from those nine spheres, which is the fount of music and melody in this world, and the cause of harmony. Then Africanus instructed him not to take delight in this world, since earth is so little and so full of torment and ill favor. Then he told him how in a certain term of years every star should come into its own place, where it first was; and all that has been done by all mankind in this world shall pass out of memory.

Then he asked Africanus to tell him fully the way to come into that heavenly happiness; and he said, “First know yourself to be immortal; and always see that you labor diligently and teach for the common profit, and you shall not fail to come speedily to that dear place that is full of joy and of bright souls. But breakers of the law, in truth, and lecherous folk, after they die, shall ever be whirled about the earth in torment, until many an age be passed; and then, all their wicked deeds forgiven, they shall come to that blessed region, to which may God send you His grace to come.”

Author: Edward Burne-Jones

Source: Archive.org

License: Public Domain

The day began to end, and dark night, which withdraws beasts from their activity, bereft me of my book for the lack of light; and I set forth to my bed, full of brooding and anxious heaviness. For I both had that which I wished not and what I wished that I had not. But at last, wearied with all the day’s labor, my spirit took rest and heavily slept; and as I lay in my sleep, I dreamed how Africanus, in the very same guise in which Scipio saw him that time before, had come and stood at the very side of my bed. When the weary hunter sleeps, quickly his mind returns to the wood; the judge dreams how his cases fare, and the carter how his carts go; the rich dream of gold, the knight fights his foes; the sick man dreams he drinks of the wine cask, the lover that he has his lady. I cannot say whether my reading of Africanus was the cause that I dreamed that he stood there; but thus he spoke, “You have done so well to look upon my old tattered book, of which Macrobius thought not a little, that I would requite you somewhat for your labor.”

Cytherea, you sweet, blessed lady, who with your fire-brand subdues whomsoever you wish, and sends me this dream, be my helper in this, for you are best able! As surely as I saw you in the north-northwest when I began to write my dream, so surely do you give me power to rhyme it and compose it!

This aforesaid Africanus took me from there and brought me out with him to a gate of a park walled with mossy stone; and over the gate on either side, carved in large letters, were verses of very diverse senses, of which I shall tell you the full meaning:

“Through me men go into that blessed place

Where hearts find health and deadly wounds find cure,

Through me men go unto the fount of Grace,

Where green and lusty May shall ever endure.

I lead men to blithe peace and joy secure.

Reader, be glad; throw off your sorrows past.

Open am I; press in and make haste fast.”

On the other side it said:

“Through me men go where all mischance betides,

Where is the mortal striking of the spear,

To which Disdain and Coldness are the guides,

Where trees no fruit or leaf shall ever bear.

This stream shall lead you to the sorrowful weir

Where fish in baleful prison lie all dry.

To shun it is the only remedy.”

These inscriptions were written, the one in gold, the other in black, and I beheld them for a long while, for at the one my heart grew hardy, and the other ever increased my fear; the first warmed me, the other chilled me. For fear of error my wit could not make its choice, to enter or to flee, to lose myself or save myself. Just as a piece of iron set between two load-stones of equal force has no power to move one way or the other—for as much as one draws the other hinders.

So it fared with me, who knew not which would be better, to enter or not, until Africanus my guide caught and pushed me in at the wide gates, saying, “Your doubt stands written on your face, though you tell it not to me. But fear not to come in, for this writing is not meant for you or for any, unless he would be Love’s servant. For in love, I believe, you have lost your sense of taste, even as a sick man loses his taste of sweet and bitter. Nevertheless, dull though you may be, you can still look upon that which you cannot do; for many a man who cannot complete a bout is nevertheless pleased to be at a wrestling match, and judges whether one or another does better. And if you have skill to set it down, I will show you something to write about.”

With that he took my hand in his, from which I took comfort and quickly went in. But Lord, how glad and at ease I was! For everywhere I cast my eyes were trees clad, each according to its kind, with everlasting leaves in fresh color and green as emerald, a joy to behold: the builder oak, eke the hardy ash, the elm the pillar and the coffin for corpses, the boxwood for horns, the holly for whip-handles, the fir to bear sails, the cypress to mourn death, the yew the bowman, the aspen for smooth shafts, the olive of peace, the drunken vine, the victor palm, and the laurel for divination.

By a river in a green meadow, where there is at all points so much sweetness, I saw a garden, full of blossomy boughs, with white, blue, yellow and red flowers; and cold fountain-streams, not at all dead, full of small shining fish with red fins and silver-bright scales. On every bough I heard the birds sing with the voice of angels in their melody. Some busied themselves to lead forth their young. The little bunnies hastened to play. Further on I noticed all about the timid roe, the buck, harts and hinds and squirrels and small beasts of gentle nature. I heard stringed instruments playing harmonies of such ravishing sweetness that God, Maker and Lord of all, never heard better, I believe. At the same time a wind, scarce could it have been gentler, made in the green leaves a soft noise which accorded with the song of the birds above. The air of that place was so mild that never was there discomfort for heat or cold. Every wholesome spice and herb grew there, and no person could age or sicken. There was a thousand times more joy than man can tell. And it would never be night there, but ever bright day in every man’s eye.

I saw Cupid our lord forging and filing his arrows under a tree beside a spring, and his bow lay ready at his feet. And meanwhile his daughter well tempered the arrow-heads in the spring, and by her cunning she piled them after as they should serve, some to slay, some to wound and pierce. Just then I was aware of Pleasure and of Fair Array and Courtesy and Joy and of Deception who has wit and power to cause a being to do folly—she was disguised, I deny it not. And under an oak, I believe, I saw Delight, standing apart with Gentle Breeding. I saw Beauty without any raiment; and Youth, full of sportiveness and jollity, Foolhardiness, Flattery, Desire, Message-sending and Bribery; and three others—their names shall not be told by me.

And upon great high pillars of jasper I saw a temple of brass strongly stand. About the temple many women were dancing ceaselessly, of whom some were beautiful themselves and some gay in dress; only in their kirtles they went, with hair unbound—that was forever their business, year by year. And on the temple I saw many hundred pairs of doves sitting, white and beautiful. Before the temple-door sat Lady Peace full gravely, holding back the curtain, and beside her Lady Patience, with pale face and wondrous discretion, sitting upon a mound of sand. Next to her were Promise and Cunning and a crowd of their followers within the temple and without.

Inside I heard a gust of sighs blowing about, hot as fire, engendered of longing, which caused every altar to blaze ever anew. And well I saw then that all the cause of sorrows that lovers endure is through the bitter goddess Jealousy. As I walked about within the temple I saw the god Priapus standing in sovereign station, his scepter in hand, and in such attire as when the ass confounded him to confusion with its outcry by night. People were busily setting upon his head garlands full of fresh, new flowers of various colors.

In a private corner I found Venus, who was noble and stately in her bearing, sporting with her porter Riches. The place was dark, but in time I saw a little light—it could scarcely have been less. Venus reposed upon a golden bed until the hot sun should seek the west. Her golden hair was bound with a golden thread, but all untressed as she lay. And one could see her naked from the breast to the head; the remnant, in truth, was well covered to my pleasure with a filmy kerchief of Valence; there was no thicker cloth that could also be transparent. The place gave forth a thousand sweet odors. Bacchus, god of wine, sat beside her, and next was Ceres, who saves all from hunger, and, as I said, the Cyprian woman lay in the midst; on their knees two young people were crying to her to be their helper.

But thus I left her lying, and further in the temple I saw how, in scorn of Diana the chaste, there hung on the wall many a broken bow of such maidens as had first wasted their time in her service. And everywhere was painted many stories, of which I shall touch on a few, such as Callisto and Atalanta and many maidens whose name I do not know. There was also Semiramis, Candace, Hercules, Byblis, Dido, Thisbe and Pyramus, Tristram and Isolt, Paris, Achilles, Helen, Cleopatra, Troilus, and Scylla, and the mother of Romulus as well—all were portrayed on the other wall, and their love and by what plight they died.

When I had returned to the sweet and green garden that I spoke of, I walked forth to comfort myself. Then I noticed how there sat a queen who was exceeding in fairness over every other creature, as the brilliant summer sun passes the stars in brightness. This noble goddess Nature was set upon a flowery hill in a verdant glade. All her halls and bowers were wrought of branches according to the art and measure of Nature.

And there was not any bird that is created through procreation that was not ready in her presence to hear her and receive her judgment. For this was Saint Valentine’s day, when every bird of every kind that men can imagine comes to this place to choose his mate. And they made an exceedingly great noise; and earth and sea and the trees and all the lakes were so full that there was scarcely room for me to stand, so full was the entire place. And just as Alan, in The Complaint of Nature, describes Nature in her features and attire, so might men find her in reality.

This noble empress, full of grace, bade every bird take his station, as they were accustomed to stand always on Saint Valentine’s day from year to year. That is to say, the birds of prey were set highest, and then the little birds who eat, as nature inclines them, worms or other things of which I speak not; but water-fowls sat the lowest in the dale; and birds that live on seed sat upon the grass, so many that it was a marvel to see.

There one could find the royal eagle, that pierces the sun with his sharp glance; and other eagles of lower race, of which clerks can tell. There was that tyrant with dun gray feathers, I mean the goshawk, that harasses other birds with his fierce ravening. There was the noble falcon, that with his feet grasps the king’s hand; also the bold sparrow-hawk, foe of quails; the merlin, that often greedily pursues the lark. The dove was there, with her meek eyes; the jealous swan, that sings at his death; and the owl also, that forebodes death; the giant crane, with his trumpet voice; thieving chough; the prating magpie; the scornful jay; the heron, foe to eels; the false lapwing, full of trickery; the starling, that can betray secrets; the tame redbreast; the coward kite; the cock, timekeeper of little thorps; the sparrow, son of Venus; the nightingale, which calls forth the fresh new leaves; the swallow, murderer of the little bees which make honey from the fresh-hued flowers; the wedded turtle-dove, with her faithful heart; the peacock, with his shining angel-feathers; the pheasant, that scorns the cock by night; the vigilant goose; the cuckoo, ever unnatural; the popinjay, full of wantonness; the drake, destroyer of his own kind; the stork, that avenges adultery; the greedy, gluttonous cormorant; the wise raven and the crow, with voice of ill-boding; the ancient thrush and the wintry fieldfare.

What more shall I say? One might find assembled in that place before the noble goddess Nature birds of every sort in this world that have feathers and stature. And each by her consent worked diligently to choose or take graciously his lady or his mate.

But to the point: Nature held on her hand a formel eagle, the noblest in shape that she ever found among her works, the gentlest and goodliest; in her every noble trait so had its seat that Nature herself rejoiced to look upon her and to kiss her beak many times. Nature, vicar of the Almighty Lord, who has knit in harmony hot, cold, heavy, light, moist, and dry in exact proportions, began to speak in a gentle voice: “Birds, take heed of what I say; and for your welfare and to further your needs I will hasten as fast as I can speak. You well know how on Saint Valentine’s day, by my statute and through my ordinance, you come to choose your mates, as I prick you with sweet pain, and then fly on your way. But I may not, to win this entire world, depart from my just order, that he who is most worthy shall begin.

“The tercel eagle, the royal bird above you in degree, as you well know, the wise and worthy one, trusty, true as steel, which you may see I have formed in every part as pleased me best—there is no need to describe his shape to you—he shall choose first and speak as he will. And after him you shall choose in order, according to your nature, each as pleases you; and, as your chance is, you shall lose or win. But whichever of you love ensnares most, to him may God send her who sighs for him most sorely.”

And at this she called the tercel and said, “My son, the choice is fallen to you. Nevertheless under this condition must be the choice of each one here, that his chosen mate will agree to his choice, whatsoever he be who would have her. From year to year this is always our custom. And whoever at this time can win grace has come here in blissful time!”

The royal tercel, with bowed head and humble appearance, delayed not and spoke: “As my sovereign lady, not as my spouse, I choose—and choose with will and heart and mind—the formel of so noble shape upon your hand. I am hers wholly and will serve her always. Let her do as she wishes, to let me live or die; I beseech her for mercy and grace, as my sovereign lady, or else let me die here presently. For surely I cannot live long in torment, for in my heart every vein is cut. Having regard only to my faithfulness, dear heart, have some pity upon my woe. And if I am found untrue to her, disobedient or willfully negligent, a boaster, or in time love elsewhere, I pray you this will be my doom: that I will be torn to pieces by these birds, upon that day when she should ever know me untrue to her or in my guilt unkind. And since no other loves her as well as I, though she never promised me love, she ought to be mine by her mercy; for I can fasten no other bond on her. Never for any woe shall I cease to serve her, however far she may roam. Say what you will, my words are done.”

Even as the fresh red rose newly blown blushes in the summer sun, so grew the color of this woman when she heard all this; she answered no word good or bad, so sorely was she abashed; until Nature said, “Daughter, fear not, be of good courage.”

Then spoke another tercel of a lower order: “That shall not be. I love her better than you, by Saint John, or at least I love her as well, and have served her longer, according to my station. If she should love for long being to me alone should be the reward; and I also dare to say, if she should find me false, unkind, a prater, or a rebel in any way, or jealous, let me be hanged by the neck. And unless I bear myself in her service as well as my wit allows me, to protect her honor in every point, let her take my life and all the wealth I have.”

Then a third tercel eagle said, “Now, sirs, you see how little time we have here, for every bird clamors to be off with his mate or lady dear, and Nature herself as well, because of the delay, will not hear half of what I would speak. Yet unless I speak I must die of sorrow. I boast not at all of long service; but it is as likely that I shall die of woe today as he who has been languishing these twenty winters. And it may well happen that a man may serve better in half a year, even if it were no longer, than another man who has served many years. I do not say this about myself, for I can do no service to my lady’s pleasure; but I dare say that I am her truest man, I believe, and would be most glad to please her. In short, until death may seize me I will be hers, whether I wake or sleep, and true in all that heart can think.”

In all my life since the day I was born never have I heard any man so noble make a plea in love or any other thing—even if a man had time and wit to rehearse their expression and their words. And this discourse lasted from the morning until the sun drew downward so rapidly. The clamor released by the birds rung so loud— “Make an end of this and let us go!”—that I well thought the forest would be splintered. They cried, “Make haste! Alas, you will ruin us! When shall your cursed pleading come to an end? How should a judge believe either side for yea or nay, without any proof?”

The goose, cuckoo and duck so loudly cried, “Kek, kek!”, “Cuckoo!”, “Quack, quack!” that the noise reverberated in my ears. The goose said, “All this is not worth a fly! But from this I can devise a remedy, and I will speak my verdict fair and soon, on behalf of the waterfowl. Let who will smile or frown.”

“And I for the worm-eating fowl,” said the foolish cuckoo; “of my own authority, for the common welfare, I will take the responsibility now, for it would be great charity to release us.” “By God, you may wait a while yet,” said the turtle-dove. “If you are he to choose who shall speak, it would be as well for him to be silent. I am among the birds that eat seed, one of the most unworthy, and of little wit—that I know well. But a creature’s tongue would be better quiet than meddling with such doings about which he knows neither rhyme nor reason. And whosoever does so, overburdens himself in foul fashion, for often one not entrusted to a duty commits offence.”

Nature, who had always an ear to the murmuring of folly at the back, said with ready tongue, “Hold your peace there! And straightway, I hope, I shall find a counsel to let you go and release you from this noise. My judgment is that you shall choose one from each bird-folk to give the verdict for you all.”

The birds all assented to this conclusion. And first the birds of prey by full election chose the tercel-falcon to define all their judgment, and decide as he wished. And they presented him to Nature and she accepted him gladly. The falcon then spoke in this fashion: “It would be hard to determine by reason which best loves this gentle woman; for each has such ready answers that none may be defeated by reasons. I cannot see of what avail are arguments; so it seems there must be battle.”

“All ready!” then cried these tercel-eagles.

“Nay, sirs,” said he, “if I dare say it, you do me wrong, my tale is not done. For, sirs, take it not amiss, I pray, it cannot go thus as you desire. Ours is the voice that has the charge over this, and you must stand by the judges’ decision. Peace, therefore! I say that it would seem in my mind that the worthiest in knighthood, who has longest followed it, the highest in degree and of gentlest blood, would be most fitting for her, if she wish it. And of these three she knows which he is, I believe, for that is easily seen.”

The waterfowl put their heads together, and after short considering, when each had spoken his tedious gabble, they said truly, by one assent, how “the goose, with her gentle eloquence, who so desires to speak for us, shall say our say,” and prayed God would help her. Then the goose began to speak for these waterfowl, and said in her cackling, “Peace! Now every man take heed and hearken what argument I shall put forth. My wits are sharp, I love no delay; I counsel him, I say, even if he were my brother, leave him if she will not love him.”

“Lo here,” said the sparrow-hawk, “a perfect argument for a goose—bad luck to her! Lo, thus it is to have a wagging tongue! Now, fool, it would be better for you to have held your peace than have shown your folly, by God! But to do thus rests not in her wit or will; for it is truly said, ‘a fool cannot be silent.’“

Laughter arose from all the birds of noble kind; and straightway the seed-eating fowl chose the faithful turtle-dove, and called her to them, and prayed her to speak the sober truth about this matter, and asked her counsel. And she answered that she would fully show her mind. “Nay, God forbid a lover should change!” said the turtle-dove, and grew all red with shame. “Though his lady may be cold for evermore, let him serve her ever until he die. In truth I praise not the goose’s counsel, for even if my lady died I would have no other mate, I would be hers until death take me.”

“By my hat, well jested!” said the duck. “That men should love forever, without cause! Who can find reason or wit there? Does one who is mirthless dance merrily? Who should care for him who is carefree? Yea, quack!” said the duck loud and long, “God knows there are more stars than a pair.”

“Now fie, churl!” said the noble falcon. “That thought came straight from the dunghill. You can not see when a thing is proper. You fare with love as owls with light; the day blinds them, but they see very well in darkness. Your nature is so low and wretched that you can not see or guess what love is.”

Then the cuckoo thrust himself forward in behalf of the worm-eating birds, and said quickly, “So that I may have my mate in peace, I care not how long you contend. Let each be single all his life; that is my counsel, since they cannot agree. This is my instruction, and there an end!”

“Yea,” said the merlin, “as this glutton has well filled his paunch, this should suffice for us all! You murderer of the hedge-sparrow on the branch, the one who brought you up, you ruthless glutton! May you live unmated, you mangler of worms! It matters nothing to you, though your tribe may perish. Go, be a stupid fool, as long as the world lasts!”

“Peace now, I command here,” said Nature, “For I have heard the opinions of all, and yet we are no nearer to our goal. But this is my final decision, that she herself shall have the choice of whom she wishes. Whosoever may be pleased or not, he whom she chooses shall have her straightway. For since it cannot here be debated who loves her best, as the falcon said, then will I grant her this favor, that she shall have him alone on whom her heart is set, and he her that has fixed his heart on her. This judgment I, Nature, make; and I cannot speak falsely, nor look with partial eye on any rank. But if it is reasonable to counsel you in choosing a mate, then surely I would counsel you to take the royal tercel, as the falcon said right wisely; for he is noblest and most worthy whom I created so well for my own pleasure; that ought to suffice you.”

The formel answered with timid voice, “Goddess of nature, my righteous lady, true it is that I am ever under your rod, just as every other creature is, and I must be yours as long as my life may last. Therefore, grant me my first request, and straightway I will speak to you my mind.”

“I grant it to you,” said Nature; and this female eagle spoke immediately in this way: “Almighty queen, until this year comes to an end I ask respite, to take counsel with myself; and after that to have my choice free. This is all that I would say. I can say no more, even if you were to slay me. In truth, as yet I will in no manner serve Venus or Cupid”

“Now since it can happen no other way,” Nature said then, “there is no more to be said here. Then I wish these birds to go their way each with his mate, so that they tarry here no longer.” And she spoke to them thus as you shall hear. “To you I speak, you tercels,” said Nature. “Be of good heart, and continue in service, all three; a year is not so long to wait. And let each of you strive according to his degree to do well. For, God knows, she is departed from you this year; and whatsoever may happen afterwards, this interval is appointed to you all.”

And when this work was all brought to an end, Nature gave every bird his mate by just accord, and they went their way. Ah, Lord! The bliss and joy that they made! For each of them took the other in his wings, and wound their necks about each other, ever thanking the noble goddess of nature. But first were chosen birds to sing, as was always their custom year by year to sing a roundel at their departure, to honor Nature and give her pleasure. The tune, I believe, was made in France. The words were such as you may here find in these verses, as I remember them.

Qui bien aime a tard oublie.

“Welcome, summer, with sunshine soft,

The winter’s tempest you will break,

And drive away the long nights black!

Saint Valentine, throned aloft,

Thus little birds sing for your sake:

Welcome, summer, with sunshine soft,

The winter’s tempest you will shake!

Good cause have they to glad them oft,

His own true-love each bird will take;

Blithe may they sing when they awake,

Welcome, summer, with sunshine soft,

The winter’s tempest you will break,

And drive away the long nights black!”

And with the shouting that the birds raised, as they flew away when their song was done, I awoke; and I took up other books to read, and still I read always. In truth I hope so to read that some day I shall meet with something of which I shall fare the better. And so I will not cease to read: Explicit tractatus de Congregacione Volucrum die sancti Valentini tentum, secundum Galfridum Chaucers. Deo gracias.

The Canterbury Tales

License: © Copyright, 2007, All Rights Reserved

Geoffrey Chaucer, translated and edited by Gerard NeCastro

Here begins the Book of the Tales of Canterbury.

The General Prologue

When the sweet showers of April have pierced to the root the dryness of March and bathed every vein in moisture by which strength are the flowers brought forth; when Zephyr also with his sweet breath has given spirit to the tender new shoots in the grove and field, and the young sun has run half his course through Aries the Ram, and little birds make melody and sleep all night with an open eye, so nature pricks them in their hearts; then people long to go on pilgrimages to renowned shrines in various distant lands, and palmers to seek foreign shores. And especially from every shire’s end in England they make their way to Canterbury, to seek the holy blessed martyr who helped them when they were sick.

One day in that season, as I was waiting at the Tabard Inn at Southwark, about to make my pilgrimage with devout heart to Canterbury, it happened that there came at night to that inn a company of twenty-nine various people, who by chance had joined together in fellowship. All were pilgrims, riding to Canterbury. The chambers and the stables were spacious, and we were lodged well. But in brief, when the sun had gone to rest, I had spoken with every one of them and was soon a part of their company, and agreed to rise early to take our way to where I have told you.

Nevertheless, while I have time and space, before this tale goes further, I think it is reasonable to tell you all the qualities of each of them, as they appeared to me, what sort of people they were, of what station and how they were fashioned. I will begin with a knight.

There was a Knight and a worthy man, who, from the time when he first rode abroad, loved chivalry, faithfulness and honor, liberality and courtesy. He was valiant in his lord’s war and had campaigned, no man farther, in both Christian and heathen lands, and ever was honored for his worth. He was at Alexandria when it was won; many times in Prussia he sat in the place of honor above knights from all nations; he had fought in Lithuania and in Russia, and no Christian man of his did so more often; he had been in Granada at the siege of Algeciras and in Belmaria; he was at Lyeys and in Attalia when they were won, and had landed with many noble armies in the Levant. He had been in fifteen mortal battles, and had thrice fought for our faith in the lists at Tremessen and always slain his foe; he had been also, long before, with the lord of Palathia against another heathen host in Turkey; and ever he had great renown. And though he was valorous, he was prudent, and he was as meek as a maiden in his bearing. In all his life he never yet spoke any discourtesy to any living creature, but was truly a perfect gentle knight. To tell you of his equipment, his horses were good but he was not gaily clad. He wore a jerkin of coarse cloth all stained with rust by his coat of mail, for he had just returned from his travels and went to do his pilgrimage.

His son was with him, a young Squire, a lover and a lusty young soldier. His locks were curled as if laid in a press. He may have been twenty years of age, of average height, amazingly nimble and great of strength. He had been, at one time, in a campaign in Flanders, Artois, and Picardy, and had borne himself well, in so little time, in hope to stand in his lady’s grace. His clothes were embroidered, red and white, like a meadow full of fresh flowers. All the day long he was singing or playing upon the flute; he was as fresh as the month of May. His coat was short, with long, wide sleeves. Well could he sit a horse and ride, make songs, joust and dance, draw and write. He loved so ardently that at nighttime he slept no more than a nightingale. He was courteous, modest and helpful, and carved before his father at table.

They had a Yeoman with them; on that journey they would have no other servants. He was clad in a coat and hood of green, and in his hand he bore a mighty bow and under his belt a neat sheaf of arrows, bright and sharp, with peacock feathers. He knew how to handle his gear like a good yeoman; his arrows did not fall short on account of any poorly adjusted feathers. His head was cropped and his face brown. He understood well all the practice of woodcraft. He wore a gay arm-guard of leather and at one side a sword and buckler; at the other a fine dagger, well fashioned and as sharp as a spear-point; on his breast an image of St. Christopher in bright silver, and over his shoulder a horn on a green baldric. He was a woodsman indeed, I believe.

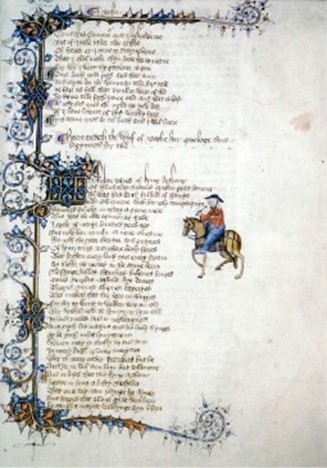

Author: Edward Burne-Jones

Source: Archive.org

License: Public Domain

There was also a nun, a Prioress, quiet and simple in her smiling; her greatest oath was “by Saint Loy.” She was named Madame Eglantine. Well she sang the divine service, intoned in a seemly manner in her nose, and spoke French elegantly, after the manner of Stratfordatte-Bow, for of Parisian French she knew nothing. She had been well taught the art of eating, and let no morsel fall from her lips, and wet but her finger-tips in the sauce. She knew how to lift and how to hold a bit so that not a drop fell upon her breast. Her pleasure was all in courtesy. She wiped her upper lip so well that no spot of grease was to be seen in her cup after she had drunk; and very dainty she was in reaching for her food. And surely she was of fine behavior, pleasant and amiable of bearing. She took pains to imitate court manners, to be stately in her demeanor and to be held worthy of reverence. But to tell you of her character, she was so charitable and so tender-hearted she would weep if she saw a mouse caught in a trap if it were dead or bleeding. She had certain small dogs, which she fed upon roasted meat or milk and finest wheaten bread. She would weep sorely if one of them died or was struck at sharply with a stick. She was all warm feeling and tender heart. Her wimple was pleated neatly. Her nose was slender, her eyes gray as glass, her mouth small and soft and red. Certainly she had a fine forehead, almost a span high; truly she was not undersized. Her cloak was neatly made, I could tell. About her arm was a coral rosary, the larger beads of green, upon which hung a brooch of shining gold; on it was engraved first an A with a crown, and after that Amor vincit omnia.

Another Nun, her chaplain, was with her, and three Priests.

There was a Monk, a very fine and handsome one, a great rider about the country-side and a lover of hunting, a manly man in all things, fit to be an abbot. He had many fine horses in his stable, and when he rode, men could hear his bridle jingling in a whistling wind as clear and loud as the chapel-bell where this lord was prior. Because the rule of St. Maurus or of St. Benedict was old and something austere, this same monk let such old things pass and followed the ways of the newer world. He gave not a plucked hen for the text that hunters are not holy, or that a careless monk (that is to say, one out of his cloister) is like a fish out of water; for that text he would not give a herring. And I said his opinion was right; why should he study and lose his wits ever poring over a book in the cloister, or toil with his hands and labor as St. Augustine bids? How shall the world be served? Let St. Augustine have his work to himself. Therefore he rode hard, followed greyhounds as swift as birds on the wing. All his pleasure was in riding and hunting the hare, and he spared no cost on those. I saw his sleeves edged at the wrist with fine dark fur, the finest in the country, and to fasten his hood under his chin he had a finely-wrought brooch of gold; in the larger end was a love-knot. His bald head shone like glass; so did his face, as if it had been anointed. He was a sleek, fat lord. His bright eyes rolled in his head, glowing like the fire under a cauldron. His boots were of rich soft leather, his horse in excellent condition. Now certainly he was a fine prelate. He was not pale, like a wasted spirit; best of any roast he loved a fat swan. His palfrey was as brown as a berry.

There was a begging Friar, lively and jolly, a very dignified fellow. In all the four orders there is not one so skilled in gay and flattering talk. He had, at his own expense, married off many young women; he was a noble pillar of his order! He was well beloved and familiar among franklins everywhere in his countryside, and also with worthy town women, for he had, as he said himself, more virtue as confessor than a parson, for he held a papal license. Very sweetly he heard confession, and his absolution was pleasant; he was an easy man to give penance, when he looked to have a good dinner. Gifts to a poor order are a sign that a man has been well confessed, he maintained; if a man gave, he knew he was contrite. For many people are so stern of heart that they cannot weep, though they suffer sorely; therefore, instead of weeping and praying, men may give silver to the poor friars. The tip of his hood was stuffed full of knives and pins as presents to fine women. And certainly he had a pleasant voice in singing, and well could play the fiddle; in singing ballads he bore off the prize. His neck was as white as the fleur-de-lis, and he was as strong as a champion. He knew all the town taverns, and every inn-keeper and bar-maid, better than the lepers and beggar-women. For it accorded not with a man of his importance to have acquaintance with sick lepers; it was not seemly, it profited not, to deal with any such poor trash, but all with rich folk and sellers of victual. But everywhere that advantage might follow he was courteous, lowly and serviceable. Nowhere was any so capable; he was the best beggar in his house, and gave a certain yearly payment so that none of his brethren might trespass on his routes. Though a widow might not have an old shoe to give, so pleasant was his “In principio,” he would have his farthing before he went. He gained more from his begging than he ever needed, I believe! He would romp about like a puppy-dog. On days of reconciliation, or love-days, he was very helpful, for he was not like a cloister-monk or a poor scholar with a threadbare cope, but like a Master of Arts or a cardinal. His half-cope was of double worsted and came from the clothes-press rounding out like a bell. He pleased his whim by lisping a little, to make his English sound sweet upon his tongue, and in his harping and singing his eyes twinkled in his head like the stars on a frosty night. This worthy friar was named Hubert.

There was a Merchant with a forked beard, in parti-colored garb. High he sat upon his horse, a Flanders beaver-hat on his head, and boots fastened neatly with rich clasps. He uttered his opinions pompously, ever tending to the increase of his own profit; at any cost he wished the sea were safeguarded between Middleburg and Orwell. In selling crown-pieces he knew how to profit by the exchange. This worthy man employed his wit cunningly; no creature knew that he was in debt, so stately he was of demeanor in bargaining and borrowing. He was a worthy man indeed, but, to tell the truth, I know not his name.

There was also a Clerk from Oxford who had long gone to lectures on logic. His horse was as lean as a rake, and he was not at all fat, I think, but looked hollow-cheeked, and grave likewise. His little outer cloak was threadbare, for he had no worldly skill to beg for his needs, and as yet had gained himself no benefice. He would rather have had at his bed’s head twenty volumes of Aristotle and his philosophy, bound in red or black, than rich robes or a fiddle or gay psaltery. Even though he was a philosopher, he had little gold in his money-box! But all that he could get from his friends he spent on books and learning, and would pray diligently for the souls of who gave it to him to stay at the schools. Of study he took most heed and care. Not a word did he speak more than was needed, and the little he spoke was formal and modest, short and quick, and full of high matter. All that he said tended toward moral virtue. Gladly would he learn and gladly teach.

There was also a Sergeant of the Law, an excellent man, wary and wise, a frequenter of the porch of Paul’s Church. He was discreet and of great distinction; or seemed such, his words were so sage. He had been judge at court, by patent and full commission; with his learning and great reputation he had earned many fees and robes. Such a man as he for acquiring goods there never was; anything that he desired could be shown to be held in unrestricted possession, and none could find a flaw in his deeds. Nowhere was there so busy a man, and yet he seemed busier than he was. He knew in precise terms every case and judgment since King William the Conqueror, and every statute fully, word for word, and none could chide at his writing. He rode in simple style in a parti-colored coat and a belt of silk with small cross-bars. Of his appearance I will not make a longer story.

Traveling with him was a Franklin, with a beard as white as a daisy, a ruddy face and a sanguine temper. Well he loved a sop of wine of a morning. He was accustomed to live in pleasure, for he was a very son of Epicurus, who held the opinion that perfect felicity stands in pleasure alone. He ever kept an open house, like a true St. Julian in his own country-side. His bread and his wine both were always of the best; never were a man’s wine-vaults better stored. His house was never without a huge supply of fish or meat; in his house it snowed meat and drink, and every fine pleasure that a man could dream of. According to the season of the year he varied his meats and his suppers. Many fat partridges were in his cage and many bream and pike in his fishpond. Woe to his cook unless his sauces were pungent and sharp, and his gear ever in order! All the long day stood a great table in his hall fully prepared. When the justices met at sessions of court, there he lorded it full grandly, and many times he sat as knight of the shire in parliament. A dagger hung at his girdle, and a pouch of taffeta, white as morning’s milk. He had been sheriff and auditor; nowhere was so worthy a vassal.

A Haberdasher, a Carpenter, a Weaver, a Dyer, and an Upholsterer were with us also, all in the same dress of a great and splendid guild. All fresh and new was their gear. Their knives were not tipped with brass but all with fine-wrought silver, like their girdles and their pouches. Each of them seemed a fair burgess to sit in a guildhall on a dais. Each for his discretion was fit to be alderman of his guild, and had goods and income sufficient for that. Their wives would have consented, I should think; otherwise, they would be at fault. It is a fair thing to be called madame, and to walk ahead of other folks to vigils, and to have a mantle carried royally before them.

They had a Cook with them for that journey, to boil chickens with the marrow-bones and tart powder-merchant and cyprus-root. Well he knew a draught of London ale! He could roast and fry and broil and stew, make dainty pottage and bake pies well. It was a great pity, it seemed to me, that he had a great ulcer on his shin, for he made capon-in-cream with the best of them.

There was a Shipman, from far in the West; for anything I know, he was from Dartmouth. He rode a nag, as well as he knew how, in a gown of coarse wool to the knee. He had a dagger hanging on a lace around his neck and under his arm. The hot summer had made his hue brown. In truth he was a good fellow: many draughts of wine had he drawn at Bordeaux while the merchant slept. He paid no heed to nice conscience; on the high seas, if he fought and had the upper hand, he made his victims walk the plank. But in skill to reckon his moon, his tides, his currents and dangers at hand, his harbors and navigation, there was none like him from Hull to Carthage. In his undertakings he was bold and shrewd. His beard had been shaken by many tempests. He knew the harbors well from Gothland to Cape Finisterre, and every creek in Spain and in Brittany. His ship was called the Maudelayne.

With us was a Doctor, a Physician; for skill in medicine and in surgery there was no peer in this entire world. He watched sharply for favorable hours and an auspicious ascendant for his patients’ treatment, for he was well grounded in astrology. He knew the cause of each malady, if it was hot, cold, dry or moist, from where it had sprung and of what humor. He was a thorough and a perfect practitioner. Having found the cause and source of his trouble, quickly he had ready the sick man’s cure. He had his apothecaries all prepared to send him electuaries and drugs, for each helped the other’s gain; their friendship was not formed of late! He knew well the old Aesculapius, Dioscorides and Rufus, Hippocrates, Haly and Galen, Serapion, Rhasis and Avicenna, Averroes, Damascene and Constantine, Bernard, Gatisden and Gilbertine. His own diet was moderate, with no excess, but nourishing and simple to digest. His study was only a little on Scripture. He was clad in red and blue-gray cloth, lined with taffeta and sendal silk. Yet he was but moderate in spending, and kept what he gained during the pestilence. Gold is a medicine from the heart in physicians’ terms; doubtless that was why he loved gold above all else.

There was a Good Wife from near Bath, but she was somewhat deaf, and that was pity. She was so skilled in making cloth that she surpassed those of Ypres and Ghent. In all the parish there was no wife who should march up to make an offering before her, and if any did, so angered she was that truly she was out of all charity. Her kerchiefs were very fine in texture; and I dare swear those that were on her head for Sunday weighed ten pounds. Her hose were of a fine scarlet and tightly fastened, and her shoes were soft and new. Her face was bold and fair and red. All her life she was a worthy woman; she had had five husbands at the church-door, besides other company in her youth, but of that there is no need to speak now. She had thrice been at Jerusalem; many distant streams had she crossed; she had been on pilgrimages to Boulogne and to Rome, to Santiago in Galicia and to Cologne. This wandering by the way had taught her various things. To tell the truth, she was gap-toothed; she sat easily on an ambling horse, wearing a fair wimple and on her head a hat as broad as a buckler or target. About her broad hips was a short riding skirt and on her feet a pair of sharp spurs. Well could she laugh and prattle in company. Love and its remedies she knew all about, I dare give my word, for she had been through the old dance.

There was a good man of religion, a poor Parson, but rich in holy thought and deed. He was also a learned man, a clerk, and would faithfully preach Christ’s gospel and devoutly instruct his parishioners. He was benign, wonderfully diligent, and patient in adversity, as he was often tested. He was loath to excommunicate for unpaid tithes, but rather would give to his poor parishioners out of the church alms and also of his own substance; in little he found sufficiency. His parish was wide and the houses far apart, but not even for thunder or rain did he neglect to visit the farthest, great or small, in sickness or misfortune, going on foot, a staff in his hand. To his sheep did he give this noble example, which he first set into action and afterward taught; these words he took out of the gospel, and this similitude he added also, that if gold will rust, what shall iron do? For if a priest upon whom we trust were to be foul, it is no wonder that an ignorant layman would be corrupt; and it is a shame (if a priest will but pay attention to it) that a shepherd should be defiled and the sheep clean. A priest should give good example by his cleanness how his sheep should live. He would not farm out his benefice, nor leave his sheep stuck fast in the mire, while he ran to London to St. Paul’s, to get an easy appointment as a chantry-priest, or to be retained by some guild, but dwelled at home and guarded his fold well, so that the wolf would not make it miscarry. He was no hireling, but a shepherd. And though he was holy and virtuous, he was not pitiless to sinful men, nor cold or haughty of speech, but both discreet and benign in his teaching; to draw folk up to heaven by his fair life and good example, this was his care. But when a man was stubborn, whether of high or low estate, he would scold him sharply. There was nowhere a better priest than he. He looked for no pomp and reverence, nor yet was his conscience too particular; but the teaching of Christ and his apostles he taught, and first he followed it himself.

With him was his brother, a Ploughman, who had drawn many cartloads of dung. He was a faithful and good toiler, living in peace and perfect charity. He loved God best at all times with all his whole heart, in good and ill fortune, and then his neighbor even as himself. He would thresh and ditch and delve for every poor person without pay, but for Christ’s sake, if he were able. He paid his tithes fairly and well on both his produce and his goods. He wore a ploughman’s frock and rode upon a mare.

There was a Reeve also and a Miller, a Summoner and a Pardoner, a Manciple and myself. There were no more.

The Miller was a stout fellow, big of bones and brawn; and well he showed them, for everywhere he went to a wrestling match he would always carry off the prize ram. He was short-shouldered and broad, a thick, knotty fellow. There was no door that he could not heave off its hinges, or break with his head at a running. His beard was as red as any sow or fox, and broad like a spade as well. Upon the very tip of his nose he had a wart, and on it stood a tuft of red hair like the bristles on a sow’s ears, and his nostrils were black and wide. At his thigh hung a sword and buckler. His mouth was as great as a great furnace. He was a teller of dirty stories and a buffoon, and it was mostly of sin and obscenity. He knew well how to steal corn and take his toll of meal three times over; and yet he had a golden thumb, by God! He wore a white coat and a blue hood. He could blow and play the bagpipe well, and with its noise he led us out of town.

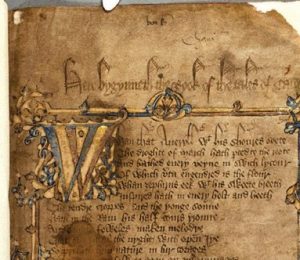

General Prologue for the Canterbury Tales from the Hengwrt manuscript.

Author: Unknown

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: Public Domain

There was a gentle Manciple of an Inn of Court, of whom other stewards might take example for craftiness in buying victuals. Whether he paid in cash or took on credit, he was so watchful in his buying that he was always ahead and in good standing. Now is it not a full fair gift of God that the wit of such an unlettered man shall surpass the wisdom of a great body of learned men? He had more than a score of masters, expert and diligent in law, of whom in that house there were a dozen worthy to be stewards of lands and revenues of any lord in England, to let him live upon his income, honorably, free from debt, unless he were mad, or live as plainly as he would; or able to help a whole shire in any case that might occur. And yet this Manciple hoodwinked all of them.

The Reeve was a slender, bilious man. His beard was shaven as close as could be, and his hair was cut short around his ears and docked in front like a priest’s. His legs were full and lean like a stick; I could see no calf. He could well keep a bin and a garner and no inspector could get the best of him. In the drought or in the wet he could foretell the yield of his grain and seed. His lord’s sheep, poultry and cattle, his dairy and swine and horses and all his stock, this Reeve had wholly under his governance, and submitted his accounts thereon ever since his lord was twenty years of age; and none could ever find him out in arrears. There was no bailiff nor herdsman nor other churl whose tricks and craftiness he didn’t know. They were as afraid of him as of the plague. His dwelling-place was a pleasant one on a heath, all shaded with green trees. Better than his lord he knew how to pick up wealth, and had a rich private hoard; he knew how to please his master cunningly by giving and lending him out of what was his master’s by right, and to win thanks for that, and a coat and hood as a reward too. In his youth he had learned a good trade and was a fine carpenter and workman. This Reeve sat upon a fine dapple gray cob named Scot. He wore a long surcoat of blue and at his side a rusty blade. He was from Norfolk, near a town they call Baldeswell. His coat was tucked up around him like a friar’s, and he always rode last of us all.

A Summoner was with us there, a fire-red cherubim-faced fellow, salt-phlegmed and pimply, with slits for eyes, scabby black eyebrows and thin ragged beard, and as hot and lecherous as a sparrow. Children were terrified at his visage. No quicksilver, white-lead, brimstone, borax nor ceruse, no cream of tartar nor any ointment that would clean and burn, could help his white blotches or the knobs on his chaps. He loved garlic, onions and leeks too well, and to drink strong wine as red as blood, and then he would talk and cry out like mad. And after drinking deep of wine he would speak no word but Latin, in which he had a few terms, two or three, learned out of some canon. No wonder was that, for he heard it all day long, and you know well how a jay can call “Walter” after hearing it a long time, as well as the pope could. But if he were tested in any other point, his learning was found to be all spent. Questio quid juris, he was always crying. He was a kind and gentle rogue; a better fellow I never knew; for a quart of wine he would allow a good fellow to have his concubine for a year and completely excuse him. Secretly he knew how to swindle anyone. And if anywhere he found a good fellow, he would teach him in such case to have no fear of the archdeacon’s excommunication, unless a man’s soul is in his purse, for it was in his purse he should be punished. “The Archdeacon’s hell is your purse,” he said. (But well I know he lied in his teeth; every guilty man should fear the church’s curse, for it will slay, just as absolution saves, and also let him beware of a significavit.) Within his jurisdiction on his own terms he held all the young people of the diocese, knew their guilty secrets, and was their chief adviser. He had a garland on his head large enough for an ale-house sign, and carried a round loaf of bread as big as a buckler.

With him rode a gentle Pardoner, of Roncesvalles, his friend and companion, who had come straight from the court of Rome. He sang loudly, “Come here, love, to me,” while the Summoner joined him with a stiff bass; never was there a trumpet of half such a sound. This Pardoner had waxy-yellow hair, hanging smooth, like a hank of flax, spread over his shoulders in thin strands. For sport he wore no hood, which was trussed up in his wallet; riding with his hair disheveled, bareheaded except for his cap, he thought he was all in the latest fashion. His eyes were glaring like a hare’s. He had a veronica sewed on his cap, and his wallet, brimful of pardons hot from Rome, lay before him on his saddle. His voice was as small as a goat’s. He had no beard nor ever would have, his face was as smooth as if lately shaven; I believe he was a mare or a gelding. But as for his trade, from Berwick to Dover there was not such another pardoner. In his bag he had a pillow-case which he said was our Lady’s kerchief, and a small piece of the sail which he said St. Peter had when he walked upon the sea and Jesus Christ caught him. He had a cross of latoun, set full of false gems, and pigs’ bones in a glass. But with these relics, when he found a poor parson dwelling in the country, in one day he gained himself more money than the parson gained in two months. And thus, with flattering deceit and tricks, he made the parson and the people his dupes. But to give him his due, after all he was a noble ecclesiastic in church; he could read well a lesson or legend and best of all sing an offertory. For he knew well that when that was done he must preach and file his tongue smooth, to win silver as he well knew how. Therefore he sang merrily and loud.

Now I have told you in few words the station, the array, the number of this company and why they were assembled in Southwark as well, at this noble inn, the Tabard, close to the Bell tavern. But now it is time to say how we behaved that same evening, when we had arrived at that inn; and afterward I will tell you of our journey and the rest of our pilgrimage.

But first I pray that by your courtesy you ascribe it not to my ill manners if I speak plainly in this matter, telling you their words and cheer, and if I speak their very words as they were. For this you know as well as I, that whoever tells a tale that another has told, he must repeat every word, as nearly as he can, although he may speak ever so rudely and freely. Otherwise, he must tell his tale falsely, or pretend, or find new words. He may not spare any, even if it were his own brother; he is bound to say one word as well as the next. Christ himself spoke plainly in Holy Scriptures and you know well there is no baseness in that. And Plato, whoever can read him, says that the word must be cousin to the deed.

I also pray you to forgive me though I have not set folk here in this tale according to their station, as they should be. My wit is short, you can well understand.

Our host put us all in good spirits, and soon brought us to supper and served us with the best of provisions. The wine was strong and very glad we were to drink. Our Host was a seemly man, fit to be marshal in a banquet-hall, a large man with bright eyes, bold in speech, wise and discreet, lacking nothing of manhood: there is not a fairer burgess in Cheapside. He was in all things a very merry fellow, and after supper, when we had paid our bills, he began to jest and speak of mirth among other things.

“Now gentle people,” he said, “truly you are heartily welcome to me, for, by my word, if I shall tell the truth, I have not seen this year so merry a company at this inn at once. I would gladly make mirth if I only knew how. And I have just now thought of a mirthful thing to give you pleasure, which shall cost nothing. You go to Canterbury, God speed you, and may the blessed martyr duly reward you! I know full well, along the way you mean to tell tales and amuse yourselves, for in truth it is no comfort or mirth to ride along dumb as a stone.

“And therefore, as I said, I will make you a game. If it please you all by common consent to stand by my words and to do as I shall tell you, now, by my father’s soul (and he is in heaven), tomorrow as you ride along, if you are not merry, I will give you my head. Hold up your hands, without more words!”

Our mind was not long to decide. We thought it not worth debating, and agreed with him without more thought, and told him to say his verdict as he wished.

“Gentle people,” said he, “please listen now, but take it not, I pray you, disdainfully. To speak briefly and plainly, this is the point, that each of you for pastime shall tell two tales in this journey to Canterbury, and two others on the way home, of things that have happened in the past. And whichever of you bears himself best, that is to say, that tells now tales most instructive and delighting, shall have a supper at the expense of us all, sitting here in this place, beside this post, when we come back from Canterbury. And to add to your sport I will gladly go with you at my own cost, and be your guide. And whoever opposes my judgment shall pay all that we spend on the way. If you agree that this will be so, tell me now, without more words, and without delay I will plan for that.”

We agreed to this thing and pledged our word with glad hearts, and prayed him to do so, and to be our ruler and to remember and judge our tales, and to appoint a supper at a certain price. We would be ruled at his will in great and small, and thus with one voice we agreed to his judgment. At this the wine was fetched, and we drank and then each went to rest without a longer stay.

In the morning, when the day began to spring, our host arose and played rooster to us all, and gathered us in a flock. Forth we rode, a little faster than a walk, to St. Thomas-a-Watering. There our Host drew up his horse and said, “Listen, gentle people, if you will. You know your agreement; I remind you of it. If what you said at the hour of evensong last night is still what you agree to this morning at the time of matins, let us see who shall tell the first tale. So may I ever drink beer or wine, whoever rebels against my judgment shall pay all that is spent on the journey. Now draw cuts, before we depart further; he who has the shortest shall begin the tales. Sir Knight, my master and my lord,” said he, “now draw your lot, for this is my will, Come nearer, my lady Prioress, and you, sir Clerk, be not shy, study not; set your hands to them, every one of you.”

Without delay every one began to draw, and in short, whether it were by chance or not, the truth is, the lot fell to the Knight, at which every one was merry and glad. He was to tell his tale, as was reasonable, according to the agreement that you have heard. What need is there for more words?

When this good man saw it was so, as one discreet and obedient to his free promise he said, “Since I begin the game, what, in God’s name, welcome be the cut! Now let us ride on, and listen to what I say.” And at that word we rode forth on our journey. And he soon began his tale with a cheerful spirit, and spoke in this way.

Here ends the Prologue of this book.

The Miller’s Tale

Here follow the words between the Host and the Miller.

The Prologue of the Miller’s Tale

When the Knight had ended his tale, in the entire crowd was there nobody, young or old, who did not say it was a noble history and worthy to be called to mind; and especially each of the gentle people. Our Host laughed and swore, “So may I thrive, this goes well! The bag is unbuckled, let see now who shall tell another tale, for truly the sport has begun well. Now you, Sir Monk, if you can, tell something to repay the Knight’s story with.”

The Miller, who had drunk himself so completely pale that he could scarcely sit on his horse, would not take off his hood or hat, or wait and mind his manners for no one, but began to cry aloud in Pilate’s voice, and swore by arms and blood and head, “I know a noble tale for the occasion, to repay the Knight’s story with.”

Our Host saw that he was all drunk with ale and said, “Wait, Robin, dear brother, some better man shall speak first; wait, and let us work thriftily.”

“By God’s soul!” he said, “I will not do that! I will speak, or else go my way!”

“Tell on, in the Devil’s name!” answered our Host. “You are a fool; your wits have been overcome.”

“Now listen, one and all! But first,” said the Miller, “I make a protestation that I am drunk; I know it by my voice. And therefore if I speak as I should not, blame it on the ale of Southwark, I pray you; for I will tell a legend and a life of a carpenter and his wife, and how a clerk made a fool of the carpenter.”

“Shut your trap!” the Reeve answered and said, “Set aside your rude drunken ribaldry. It is a great folly and sin to injure or defame any man, and to bring woman into such bad reputation. You can say plenty about other matters.

This drunken Miller answered back immediately and said, “Oswald, dear brother, he is no cuckold who has no wife. But I do not say, therefore, that you are one. There are many good wives, and always a thousand good to one bad. That you know well yourself, if you have not gone mad. Why are you angry now with my tale? I have a wife as well as you, by God, yet for all the oxen in my plough I would not presume to be able to judge myself if I may be a cuckold; I will believe well I am not one. A husband should not be too inquisitive about God’s private matters, nor of his wife’s. He can find God’s plenty there; he need not inquire about the remainder.”

What more can I say, but this Miller would withhold his word for nobody, and told his churl’s tale in his own fashion. I think that I shall retell it here. And therefore I beg every gentle creature, for the love of God, not to judge that I tell it thus out of evil intent, but only because I must truly repeat all their tales, whether they are better or worse, or else tell some of my matter falsely. And therefore whoever wishes not to hear it, let them turn the leaf over and choose another tale; for they shall find plenty of historical matters, great and small, concerning noble deeds, and morality and holiness as well. Do not blame me if you choose incorrectly. The Miller is a churl, you know well, and so was the Reeve (and many others), and the two of them spoke of ribaldry. Think well, and do not blame me, and people should not take a game seriously as well.

Here ends the Prologue.

Here begins the Miller’s Tale.

A while ago there dwelt at Oxford a rich churl fellow, who took guests as boarders. He was a carpenter by trade. With him dwelt a poor scholar who had studied the liberal arts, but all his delight was turned to learning astrology. He knew how to work out certain problems; for instance, if men asked him at certain celestial hours when there should be drought or rain, or what should happen in any matter; I cannot count every one.

This clerk was named gentle Nicholas. He was well skilled in secret love and consolation; and he was also sly and secretive about it; and as meek as a maiden to look upon. He had a chamber to himself in that lodging-house, without any company, and handsomely decked with sweet herbs; and he himself was as sweet as the root of licorice or any setwall. His Almagest, and other books great and small, his astrolabe, which he used in his art, and his counting-stones for calculating, all lay neatly by themselves on shelves at the head of his bed.

His clothes-press was covered with a red woolen cloth, and above it was set a pleasant psaltery, on which he made melody at night so sweetly that the entire chamber was full of it. He would sing the hymn Angelus ad Virginem, and after that the King’s Note. Often was his merry throat blessed. And so this sweet clerk passed his time by help of what income he had and his friends provided.

This carpenter had newly wedded a wife, eighteen years of age, whom he loved more than his own soul. He was jealous, and held her closely caged, for she was young, and he was much older and judged himself likely to be made a cuckold.

His wit was rude, and he didn’t know Cato’s teaching that instructed that men should wed their equal. Men should wed according to their own station in life, for youth and age are often at odds. But since he had fallen into the snare, he must endure his pain, like other people.

This young wife was fair, and her body moreover was as graceful and slim as any weasel. She wore a striped silken belt, and over her loins an apron white as morning’s milk, all flounced out. Her smock was white and embroidered on the collar, inside and outside, in front and in back, with coal-black silk; and of the same black silk were the strings of her white hood, and she wore a broad band of silk, wrapped high about her hair.

And surely she had a lecherous eye; her eyebrows were arched and black as a sloe berry, and partly plucked out to make them narrow. She was more delicious to look on than the young pear-tree in bloom, and softer than a lamb’s wool. From her belt hung a leather purse, tasseled with silk and with beads of brass.

In all this world there is no man so wise who could imagine such a wench, or so lively a little doll. Her hue shone more brightly than the noble newly forged in the Tower. And as for her singing, it was as loud and lively as a swallow’s sitting on a barn. And she could skip and make merry as any kid or calf following its mother. Her mouth was sweet as honeyed ale or mead, or a hoard of apples laid in the hay or heather. She was skittish as a jolly colt, tall as a mast, and upright as a bolt. She wore a brooch on her low collar as broad as the embossed center of a shield, and her shoes were laced high on her legs. She was a primrose, a pig’s-eye, for a lord to lie in his bed or even a yeoman to wed.

Now sir, and again sir, it so chanced that this gentle Nicholas fell to play and romp with this young wife, as clerks are very artful and sly, on a day when her husband was at Osney. And secretly he caught hold of her genitalia and said: “Surely, unless you will love me, sweetheart, I shall die for my secret love of you. And he held her hard by the thighs and said, “Sweetheart, love me now, or I will die, may God save me!”

She sprang back like a colt in the halter, and wriggled away with her head. “I will not kiss you, in faith,” she said. Why, let me be, let me be, Nicholas, or I will cry out, ‘Alas! Help!’ Take away your hands, by your courtesy!”

But this Nicholas began to beg for her grace, and spoke so fairly and made such offers that at last she granted him her love and swore by Saint Thomas of Kent that she would do his will when she should see her chance.

“My husband is so jealous that unless you are secretive and watch your time, I know very well I am no better than dead. You must be very sly in this thing.”

“No, have no fear about that,” said Nicholas. “A clerk has spent his time poorly if he can not beguile a carpenter!”

And thus they were agreed and pledged to watch for a time, as I have told. When Nicholas had done so, petted her well on her limbs, and kissed her sweetly, he took his psaltery and made melody and played fervently.

Then it happened on a holy day that this wife went to the parish church to work Christ’s own works. Her forehead shone as bright as day, since she had scrubbed it when she had finished her tasks.

Now at that church there was a parish clerk named Absolom. His hair was curly and shone like gold, and spread out like a large broad fan; its neat part ran straight and even. His complexion was rosy, and his eyes as gray as goose-quills. His leather shoes were carved in such a way that they resembled a window in Paul’s Church. He went clad precisely and neatly all in red hose and a kirtle of a light watchet-blue; the laces were set in it fair and thick, and over it he had a lively surplice, as white as a blossom on a twig. God bless me, but he was a sweet lad!

He knew well how to clip and shave and let blood, and make a quittance or a charter for land. He could trip and dance in twenty ways in the manner of Oxford in that day, and cast with his legs back and forth, and play songs on a small fiddle. He could play on his cittern as well, and sometimes sang in a loud treble. In the whole town there was no brew-house or tavern where any tapster might be that he did not visit in his merrymaking. But to tell the truth he was some-what squeamish about farting and rough speech.

This Absalom, so pretty and fine, went on this holy day with a censer, diligently incensing the wives of the parish, and he cast many longing looks on them, and especially on this carpenter’s wife. To look at her seemed to him a sweet employment, as she was so sweet and proper and lusty; I dare say, if she had been a mouse and he a cat, he would have pounced on her immediately. And this sweet parish-clerk had such a love-longing in his heart that at the offertory he would take nothing from any wife; for courtesy, he said, he would take none.

When at night the moon shone very beautifully and Absalom intended to remain awake all night for love’s sake, he took his cittern and went forth, amorous and jolly, until he came to the carpenter’s house a little after the cocks had crowed, and pulled himself up by a casement-window.

Dear lady, if your will so be,

I pray you that you pity me

He sang in his sweet small voice, in nice harmony with his cittern.

This carpenter woke, heard his song and said without hesitation to his wife, “What, Alison! Don’t you hear Absalom chanting this way under our own bedroom-wall?”

“Yes, God knows, John,” she answered him, “I hear every bit of it.”

Thus it went on; what would you have better than well-enough? From day to day this jolly Absalom wooed her until he was all woe-begone. He remained awake all night and all day, he combed his spreading locks and preened himself, he wooed her by go-betweens and agents, and swore he would be her own page; he sang quavering like a nightingale; he sent her mead, and wines sweetened and spiced, and wafers piping hot from the coals, and because she was from the town he proffered her money. For some people will be won by rich gifts and some by blows and some by courtesy. Sometimes, to show his cheerfulness and skill, he would play Herod on a high scaffold.

But in such a case what could help him? She so loved gentle Nicholas that Absalom may as well go blow the buck’s-horn. For all his labor he had nothing but scorn, and thus she made Absalom her ape and turned all his earnest to a joke. This proverb is true—it is no lie. Men say it is just so: “The sly nearby one makes the far dear one loathed.” For though Absalom may go mad for it, because he was far from her eye, this nearby Nicholas stood in his light. Now bear yourself well, gentle Nicholas, for Absalom may wail and sing “Alack!”

And so it happened one Saturday that the carpenter had gone to Oseney, and gentle Nicholas and Alison had agreed upon this, that Nicholas would create a ruse to beguile this poor jealous husband; and if the game went as planned, she should be his, for this was his desire and hers also. And immediately, without more words, Nicholas would delay no longer, but had food and drink for a day or two carried softly into his chamber, and instructed her say to her husband, if he asked about him, that she did not know where he was; that she had not set eyes upon him all that day and she believed he was in some malady, for not by any crying out could her maid rouse him; he would not answer at all, for nothing.

Thus passed forth all that Saturday; Nicholas lay still in his chamber, and ate and slept or did what he wished, until Sunday toward sundown. This simple carpenter had great wonder about Nicholas, what could ail him. “By Saint Thomas,” he said, “I am afraid all is not well with Nicholas. God forbid that he has died suddenly! This world nowadays is so ticklish, surely; to-day I saw carried to church a corpse that I saw at work last Monday. Go up, call at his door,” he said to his boy, “or knock with a stone; see how it is, and tell me straight.”

This boy went up sturdily, stood at the chamber-door, and cried and knocked like mad: “What! How! What are you doing, master Nicholas? How can you sleep all day long?”

But all was for nothing; he heard not a word. Then he found a hole, low down in the wall, where the cat would usually creep in; and through that he looked far into it and at last caught sight of him.

Nicholas sat ever gaping upward as if he were peering at the new moon. Down went the boy, and told his master in what plight he saw this man.

The carpenter began to cross himself and said, “Help us, Saint Frideswide! People know little what shall happen to them. This man with his astronomy is fallen into some madness or some fit; I always thought how it would end this way. Men were not intended to know God’s secrets. Yes, happy is an unlearned man that never had schooling and knows nothing but his beliefs!

“So fared another clerk with his astronomy; he walked in the fields to look upon the stars, to see what was to happen, until he fell into a clay-pit that he did not see! But yet, by Saint Thomas, I am very sorry about gentle Nicholas. By Jesus, King of Heaven, he shall be scolded for his studying if I may. Get me a staff, Robin, so that I can pry under the door while you heave it up. I believe we shall rouse him from his studying!”