The Romance of the Three Kingdoms

Luo Guanzhong

Written in the 14th century C.E.

China

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is one of the stories known as the “Four Classic Novels” or “Four Great Masterpieces” of Chinese literature (the other three being Water Margin, Journey to the West, and Dream of the Red Chamber). Although it was written in the 14th century C.E., the story is based on historical events from a thousand years earlier: during the late Han dynasty and the Three Kingdoms Period (starting in 169 C.E. and ending in 280 C.E.). The story depicts the conflicts among the Wu, Wei, and Shu kingdoms. The characters are based on actual people, with the requisite alterations that are expected in fiction (such as the occasional warrior with superhuman strength, and other legendary and mythic elements). The story is 120 chapters long, with literally hundreds of characters to follow. The selections in the anthology begin with the introductory chapter, which includes how one group of heroes meets. The long selection is from the most well-known episode in the story: the Battle of Red Cliffs (208209 C.E.). The Romance of the Three Kingdoms continues to be a popular work, with movies, video games, comics, television series, and card games based on the story.

Written by Laura J. Getty

Romance of the Three Kingdoms

Luo Quanzhong, translated by C. H. Brewitt-Taylor

License: Public Domain

Chapter 1

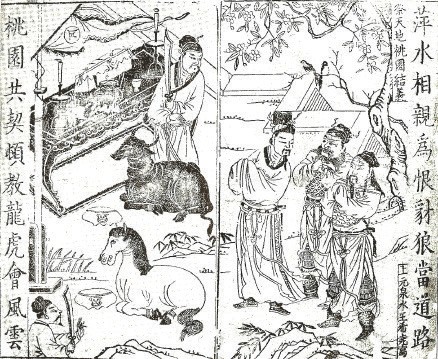

Three Heroes Swear Brotherhood In The Peach Garden; One Victory Shatters The Rebels In Battlegrounds.

The world under heaven, after a long period of division, tends to unite; after a long period of union, tends to divide. This has been so since antiquity. When the rule of the Zhou Dynasty weakened, seven contending kingdoms sprang up, warring one with another until the kingdom of Qin prevailed and possessed the empire. But when Qin’s destiny had been fulfilled, arose two opposing kingdoms, Chu and Han, to fight for the mastery. And Han was the victor.

The rise of the fortunes of Han began when Liu Bang the Supreme Ancestor slew a white serpent to raise the banners of uprising, which only ended when the whole empire belonged to Han (BC 202). This magnificent heritage was handed down in successive Han emperors for two hundred years, till the rebellion of Wang Mang caused a disruption. But soon Liu Xiu the Latter Han Founder restored the empire, and Han emperors continued their rule for another two hundred years till the days of Emperor Xian, which were doomed to see the beginning of the empire’s division into three parts, known to history as The Three Kingdoms.

But the descent into misrule hastened in the reigns of the two predecessors of Emperor Xian—Emperors Huan and Ling—who sat in the dragon throne about the middle of the second century.

Emperor Huan paid no heed to the good people of his court, but gave his confidence to the Palace eunuchs. He lived and died, leaving the scepter to Emperor Ling, whose advisers were Regent Marshal Dou Wu and Imperial Guardian Chen Fan. Dou Wu and Chen Fan, disgusted with the abuses of the eunuchs in the affairs of the state, plotted the destruction for the power-abusing eunuchs. But Chief Eunuch Cao Jie was not to be disposed of easily. The plot leaked out, and the honest Dou Wu and Chen Fan were put to death, leaving the eunuchs stronger than before.

It fell upon the day of full moon of the fourth month, the second year, in the era of Established Calm (AD 168), that Emperor Ling went in state to the Hall of Virtue. As he drew near the throne, a rushing whirlwind arose in the corner of the hall and, lo! from the roof beams floated down a monstrous black serpent that coiled itself up on the very seat of majesty. The Emperor fell in a swoon. Those nearest him hastily raised and bore him to his palace, while the courtiers scattered and fled. The serpent disappeared.

But there followed a terrific tempest, thunder, hail, and torrents of rain, lasting till midnight and working havoc on all sides. Two years later the earth quaked in Capital Luoyang, while along the coast a huge tidal wave rushed in which, in its recoil, swept away all the dwellers by the sea. Another evil omen was recorded ten years later, when the reign title was changed to Radiant Harmony (AD 178): Certain hens suddenly crowed. At the new moon of the sixth month, a long wreath of murky cloud wound its way into the Hall of Virtue, while in the following month a rainbow was seen in the Dragon Chamber. Away from the capital, a part of the Yuan Mountains collapsed, leaving a mighty rift in the flank.

Such were some of various omens. Emperor Ling, greatly moved by these signs of the displeasure of Heaven, issued an edict asking his ministers for an explanation of the calamities and marvels.

Court Counselor Cai Yong replied bluntly: “Falling rainbows and changes of fowls’ sexes are brought about by the interference of empresses and eunuchs in state affairs.”

The Emperor read this memorial with deep sighs, and Chief Eunuch Cao Jie, from his place behind the throne, anxiously noted these signs of grief. An opportunity offering, Cao Jie informed his fellows, and a charge was trumped up against Cai Yong, who was driven from the court and forced to retire to his country house.

With this victory the eunuchs grew bolder. Ten of them, rivals in wickedness and associates in evil deeds, formed a powerful party known as the Ten Regular Attendants—Zhang Rang, Zhao Zhong, Cheng Kuang, Duan Gui, Feng Xu, Guo Sheng, Hou Lan, Jian Shuo, Cao Jie, and Xia Yun.

One of them, Zhang Rang, won such influence that he became the Emperor’s most honored and trusted adviser. The Emperor even called him “Foster Father”. So the corrupt state administration went quickly from bad to worse, till the country was ripe for rebellion and buzzed with brigandage.

At this time in the county of Julu was a certain Zhang family, of whom three brothers bore the name of Zhang Jue, Zhang Ba, and Zhang Lian, respectively. The eldest Zhang Jue was an unclassed graduate, who devoted himself to medicine. One day, while culling simples in the woods, Zhang Jue met a venerable old gentleman with very bright, emerald eyes and fresh complexion, who walked with an oak-wood staff. The old man beckoned Zhang Jue into a cave and there gave him three volumes of The Book of Heaven.

“This book,” said the old gentleman, “is the Essential Arts of Peace. With the aid of these volumes, you can convert the world and rescue humankind. But you must be single-minded, or, rest assured, you will greatly suffer.”

With a humble obeisance, Zhang Jue took the book and asked the name of his benefactor.

“I am Saint Hermit of the Southern Land,” was the reply, as the old gentleman disappeared in thin air.

Zhang Jue studied the wonderful book eagerly and strove day and night to reduce its precepts to practice. Before long, he could summon the winds and command the rain, and he became known as the Mystic of the Way of Peace.

In the first month of the first year of Central Stability (AD 184), there was a terrible pestilence that ran throughout the land, whereupon Zhang Jue distributed charmed remedies to the afflicted. The godly medicines brought big successes, and soon he gained the tittle of the Wise and Worthy Master. He began to have a following of disciples whom he initiated into the mysteries and sent abroad throughout all the land. They, like their master, could write charms and recite formulas, and their fame increased his following.

Zhang Jue began to organize his disciples. He established thirty-six circuits, the larger with ten thousand or more members, the smaller with about half that number. Each circuit had its chief who took the military title of General. They talked wildly of the death of the blue heaven and the setting up of the golden one; they said a new cycle was beginning and would bring universal good fortune to all members; and they persuaded people to chalk the symbols for the first year of the new cycle on the main door of their dwellings.

With the growth of the number of his supporters grew also the ambition of Zhang Jue. The Wise and Worthy Master dreamed of empire. One of his partisans, Ma Yuanyi, was sent bearing gifts to gain the support of the eunuchs within the Palace.

To his brothers Zhang Jue said, “For schemes like ours always the most difficult part is to gain the popular favor. But that is already ours. Such an opportunity must not pass.”

And they began to prepare. Many yellow flags and banners were made, and a day was chosen for the uprising. Then Zhang Jue wrote letters to Feng Xu and sent them by one of his followers, Tang Zhou, who alas! betrayed his trust and reported the plot to the court. The Emperor summoned the trusty Regent Marshal He Jin and bade him look to the issue. Ma Yuanyi was at once taken and beheaded. Feng Xu and many others were cast into prison.

The plot having thus become known, the Zhang brothers were forced at once to take the field. They took up grandiose titles: Zhang Jue the Lord of Heaven, Zhang Ba the Lord of Earth, and Zhang Lian the Lord of Human. And in these names they put forth this manifesto:

“The good fortune of the Han is exhausted, and the Wise and Worthy Man has appeared. Discern the will of Heaven, O ye people, and walk in the way of righteousness, whereby alone ye may attain to peace.”

Support was not lacking. On every side people bound their heads with yellow scarves and joined the army of the rebel Zhang Jue, so that soon his strength was nearly half a million strong, and the official troops melted away at a whisper of his coming.

Regent Marshal and Imperial Guardian, He Jin, memorialized for general preparations against the Yellow Scarves, and an edict called upon everyone to fight against the rebels. In the meantime, three Imperial Commanders—Lu Zhi, Huangfu Song, and Zhu Jun—marched against them in three directions with veteran soldiers.

Meanwhile Zhang Jue led his army into Youzhou, the northeastern region of the empire. The Imperial Protector of Youzhou was Liu Yan, a scion of the Imperial House. Learning of the approach of the rebels, Liu Yan called in Commander Zhou Jing to consult over the position.

Zhou Jing said, “They are many and we few. We must enlist more troops to oppose them.”

Liu Yan agreed, and he put out notices calling for volunteers to serve against the rebels. One of these notices was posted up in the county of Zhuo, where lived one man of high spirit.

This man was no mere bookish scholar, nor found he any pleasure in study. But he was liberal and amiable, albeit a man of few words, hiding all feeling under a calm exterior. He had always cherished a yearning for high enterprise and had cultivated the friendship of humans of mark. He was tall of stature. His ears were long, the lobes touching his shoulders, and his hands hung down below his knees. His eyes were very big and prominent so that he could see backward past his ears. His complexion was as clear as jade, and he had rich red lips.

He was a descendant of Prince Sheng of Zhongshan whose father was the Emperor Jing (reigned BC 157-141), the fourth emperor of the Han Dynasty. His name was Liu Bei. Many years before, one of his forbears had been the governor of that very county, but had lost his rank for remissness in ceremonial offerings. However, that branch of the family had remained on in the place, gradually becoming poorer and poorer as the years rolled on. His father Liu Hong had been a scholar and a virtuous official but died young. The widow and orphan were left alone, and Liu Bei as a lad won a reputation for filial piety.

At this time the family had sunk deep in poverty, and Liu Bei gained his living by selling straw sandals and weaving grass mats. The family home was in a village near the chief city of Zhuo. Near the house stood a huge mulberry tree, and seen from afar its curved profile resembled the canopy of a wagon. Noting the luxuriance of its foliage, a soothsayer had predicted that one day a man of distinction would come forth from the family.

As a child, Liu Bei played with the other village children beneath this tree, and he would climb up into it, saying, “I am the Son of Heaven, and this is my chariot!” His uncle, Liu Yuanqi, recognized that Liu Bei was no ordinary boy and saw to it that the family did not come to actual want.

When Liu Bei was fifteen, his mother sent him traveling for his education. For a time he served Zheng Xuan and Lu Zhi as masters. And he became great friends with Gongsun Zan.

Liu Bei was twenty-eight when the outbreak of the Yellow Scarves called for soldiers. The sight of the notice saddened him, and he sighed as he read it.

Suddenly a rasping voice behind him cried, “Sir, why sigh if you do nothing to help your country?”

Turning quickly he saw standing there a man about his own height, with a bullet head like a leopard’s, large eyes, a swallow pointed chin, and whiskers like a tiger’s . He spoke in a loud bass voice and looked as irresistible as a dashing horse. At once Liu Bei saw he was no ordinary man and asked who he was.

“Zhang Fei is my name,” replied the stranger. “I live near here where I have a farm; and I am a wine seller and a butcher as well; and I like to become acquainted with worthy people. Your sighs as you read the notice drew me toward you.”

Liu Bei replied, “I am of the Imperial Family, Liu Bei is my name. And I wish I could destroy these Yellow Scarves and restore peace to the land, but alas! I am helpless.”

“I have the means,” said Zhang Fei. “Suppose you and I raised some troops and tried what we could do.”

This was happy news for Liu Bei, and the two betook themselves to the village inn to talk over the project. As they were drinking, a huge, tall fellow appeared pushing a hand-cart along the road. At the threshold he halted and entered the inn to rest awhile and he called for wine.

“And be quick!” added he. “For I am in haste to get into the town and offer myself for the army.”

Liu Bei looked over the newcomer, item by item, and he noted the man had a huge frame, a long beard, a vivid face like an apple, and deep red lips. He had eyes like a phoenix’s and fine bushy eyebrows like silkworms. His whole appearance was dignified and awe-inspiring. Presently, Liu Bei crossed over, sat down beside him and asked his name.

“I am Guan Yu,” replied he. “I am a native of the east side of the river, but I have been a fugitive on the waters for some five years, because I slew a ruffian who, since he was wealthy and powerful, was a bully. I have come to join the army here.”

Then Liu Bei told Guan Yu his own intentions, and all three went away to Zhang Fei’s farm where they could talk over the grand project.

Said Zhang Fei, “The peach trees in the orchard behind the house are just in full flower. Tomorrow we will institute a sacrifice there and solemnly declare our intention before Heaven and Earth, and we three will swear brotherhood and unity of aims and sentiments: Thus will we enter upon our great task.”

Both Liu Bei and Guan Yu gladly agreed.

All three being of one mind, next day they prepared the sacrifices, a black ox, a white horse, and wine for libation. Beneath the smoke of the incense burning on the altar, they bowed their heads and recited this oath:

“We three—Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei—though of different families, swear brotherhood, and promise mutual help to one end. We will rescue each other in difficulty; we will aid each other in danger. We swear to serve the state and save the people. We ask not the same day of birth, but we seek to die together. May Heaven, the all-ruling, and Earth, the all-producing, read our hearts. If we turn aside from righteousness or forget kindliness, may Heaven and Human smite us!”

They rose from their knees. The two others bowed before Liu Bei as their elder brother, and Zhang Fei was to be the youngest of the trio. This solemn ceremony performed, they slew other oxen and made a feast to which they invited the villagers. Three hundred joined them, and all feasted and drank deep in the Peach Garden.

The next day weapons were mustered. But there were no horses to ride. This was a real grief. But soon they were cheered by the arrival of two horse dealers with a drove of horses.

“Thus does Heaven help us!” said Liu Bei.

And the three brothers went forth to welcome the merchants. They were Zhang Shiping and Su Shuang from Zhongshan. They went northwards every year to buy horses. They were now on their way home because of the Yellow Scarves. The brothers invited them to the farm, where wine was served before them. Then Liu Bei told them of the plan to strive for tranquillity. Zhang Shiping and Su Shuang were glad and at once gave the brothers fifty good steeds, and beside, five hundred ounces of gold and silver and one thousand five hundred pounds of steel fit for the forging of weapons.

The brothers expressed their gratitude, and the merchants took their leave. Then blacksmiths were summoned to forge weapons. For Liu Bei they made a pair of ancient swords; for Guan Yu they fashioned a long-handled, curve blade called Green-Dragon Saber, which weighed a full one hundred pounds; and for Zhang Fei they created a ten-foot spear called Serpent Halberd. Each too had a helmet and full armor.

When weapons were ready, the troop, now five hundred strong, marched to Commander Zhou Jing, who presented them to Imperial Protector Liu Yan. When the ceremony of introduction was over, Liu Bei declared his ancestry, and Liu Yan at once accorded him the esteem due to a relation.

Before many days it was announced that the rebellion had actually broken out, and a Yellow Scarves chieftain, Cheng Yuanzhi, had invaded the region with a body of fifty thousand rebels. Liu Yan bade Zhou Jing and the three brothers to go out to oppose them with the five hundred troops. Liu Bei joyfully undertook to lead the van and marched to the foot of the Daxing Hills where they saw the rebels. The rebels wore their hair flying about their shoulders, and their foreheads were bound with yellow scarves.

When the two armies had been drawn up opposite each other, Liu Bei rode to the front, Guan Yu to his left, Zhang Fei to his right.

Flourishing his whip, Liu Bei began to hurl reproaches at the rebels, crying, “O malcontents! Why not dismount and be bound?”

Their leader Cheng Yuanzhi, full of rage, sent out one general, Deng Mao, to begin the battle. At once rode forward Zhang Fei, his serpent halberd poised to strike. One thrust and Deng Mao rolled off his horse, pierced through the heart. At this Cheng Yuanzhi himself whipped up his steed and rode forth with sword raised ready to slay Zhang Fei. But Guan Yu swung up his ponderous green-dragon saber and rode at Cheng Yuanzhi. At the sight, fear seized upon Cheng Yuanzhi, and before he could defend himself, the great saber fell, cutting him in halves.

Two heroes new to war’s alarms,

Ride boldly forth to try their arms.

Their doughty deeds three kingdoms tell,

And poets sing how these befell.

Their leader fallen, the rebels threw away their weapons and fled. The official soldiers dashed in among them. Many thousands surrendered and the victory was complete. Thus this part of the rebellion was broken up.

On their return, Liu Yan personally met them and distributed rewards. But the next day, letters came from Imperial Protector Gong Jing of Qingzhou Region saying that the rebels were laying siege to the chief city and it was near falling. Help was needed quickly.

“I will go,” said Liu Bei as soon as he heard the news.

And he set out at once with his own soldiers, reinforced by a body of five thousand under Zhou Jing. The rebels, seeing help coming, at once attacked most fiercely. The relieving force being comparatively small could not prevail and retired some ten miles, where they made a camp.

“They are many and we but few,” said Liu Bei to his brothers. “We can only beat them by superior strategy.”

So they prepared an ambush. Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, each with a goodly party, went behind the hills, right and left, and there hid. When the gongs beat they were to move out to support the main army.

These preparations made, the drums rolled noisily for Liu Bei to advance. The rebels also came forward. But Liu Bei suddenly retired. Thinking this was their chance, the rebels pressed forward and were led over the hills. Then suddenly the gongs sounded for the ambush. Guan Yu and Zhang Fei poured out from right and left as Liu Bei faced around to meet the rebels. Under three-side attack, the rebels lost heavily and fled to the walls of Qingzhou City. But Imperial Protector Gong Jing led out an armed body to attack them, and the rebels were entirely defeated and many slain. Qingzhou was no longer in danger.

Though fierce as tigers soldiers be,

Battles are won by strategy.

A hero comes; he gains renown,

Already destined for a crown.

After the celebrations in honor of victory were over, Commander Zhou Jing proposed to return to Youzhou.

But Liu Bei said, “We are informed that Imperial Commander Lu Zhi has been struggling with a horde of rebels led by Zhang Jue at Guangzong. Lu Zhi was once my teacher, and I want to go help him.”

So Liu Bei and Zhou Jing separated, and the three brothers with their troops made their way to Guangzong. They found Lu Zhi’s camp, were admitted to his presence, and declared the reason of their coming. The Commander received them with great joy, and they remained with him while he made his plans.

At that time Zhang Jue’s one hundred fifty thousand troops and Lu Zhi’s fifty thousand troops were facing each other. Neither had had any success.

Lu Zhi said to Liu Bei, “I am able to surround these rebels here. But the other two brothers, Zhang Ba and Zhang Lian, are strongly entrenched opposite Huangfu Song and Zhu Jun at Yingchuan. I will give you a thousand more troops, and with these you can go to find out what is happening, and we can then settle the moment for concerted attack.”

So Liu Bei set off and marched as quickly as possible to Yingchuan. At that time the imperial troops were attacking with success, and the rebels had retired upon Changshe. They had encamped among the thick grass.

Seeing this, Huangfu Song said to Zhu Jun, “The rebels are camping in the field. We can attack them by fire.”

So the Imperial Commanders bade every man cut a bundle of dry grass and laid an ambush. That night the wind blew a gale, and at the second watch they started a blaze. At the same time Huangfu Song and Zhu Jun’s troops attacked the rebels and set their camp on fire. The flames rose to the very heaven. The rebels were thrown into great confusion. There was no time to saddle horses or don armor: They fled in all directions.

The battle continued until dawn. Zhang Lian and Zhang Ba, with a group of flying rebels, found a way of escape. But suddenly a troop of soldiers with crimson banners appeared to oppose them. Their leader was a man of medium stature with small eyes and a long beard. He was Cao Cao, a Beijuo man, holding the rank of Cavalry Commander. His father was Cao Song, but he was not really a Cao. Cao Song had been born to the Xiahou family, but he had been brought up by Eunuch Cao Teng and had taken this family name.

As a young man Cao Cao had been fond of hunting and delighted in songs and dancing. He was resourceful and full of guile. An uncle, seeing the young fellow so unsteady, used to get angry with him and told his father of his misdeeds. His father remonstrated with him.

But Cao Cao made equal to the occasion. One day, seeing his uncle coming, he fell to the ground in a pretended fit. The uncle alarmed ran to tell his father, who came, and there was the youth in most perfect health.

“But your uncle said you were in a fit. Are you better?” said his father.

“I have never suffered from fits or any such illness,” said Cao Cao. “But I have lost my uncle’s affection, and he has deceived you.”

Thereafter, whatever the uncle might say of his faults, his father paid no heed. So the young man grew up licentious and uncontrolled.

A man of the time named Qiao Xuan said to Cao Cao, “Rebellion is at hand, and only a man of the greatest ability can succeed in restoring tranquillity. That man is yourself.”

And He Yong of Nanyang said of him, “The dynasty of Han is about to fall. He who can restore peace is this man and only he.”

Cao Cao went to inquire his future of a wise man of Runan named Xu Shao.

“What manner of man am I?” asked Cao Cao.

The seer made no reply, and again and again Cao Cao pressed the question.

Then Xu Shao replied, “In peace you are an able subject; in chaos you are a crafty hero!”

Cao Cao greatly rejoiced to hear this.

Cao Cao graduated at twenty and earned a reputation of piety and integrity. He began his career as Commanding Officer in a county within the Capital District. In the four gates of the city he guarded, he hung up clubs of various sorts, and he would punish any breach of the law whatever the rank of the offender. Now an uncle of Eunuch Jian Shuo was found one night in the streets with a sword and was arrested. In due course he was beaten. Thereafter no one dared to offend again, and Cao Cao’s name became heard. Soon he became a magistrate of Dunqiu.

At the outbreak of the Yellow Scarves, Cao Cao held the rank of General and was given command of five thousand horse and foot to help fight at Yingchuan. He just happened to fall in with the newly defeated rebels whom he cut to pieces. Thousands were slain and endless banners and drums and horses were captured, together with huge sums of money. However, Zhang Ba and Zhang Lian got away; and after an interview with Huangfu Song, Cao Cao went in pursuit of them.

Meanwhile Liu Bei and his brothers were hastening toward Yingchuan, when they heard the din of battle and saw flames rising high toward the sky. But they arrived too late for the fighting. They saw Huangfu Song and Zhu Jun to whom they told the intentions of Lu Zhi.

“The rebel power is quite broken here,” said the commanders, “but they will surely make for Guangzong to join Zhang Jue. You can do nothing better than hasten back.”

The three brothers thus retraced their steps. Half way along the road they met a party of soldiers escorting a prisoner in a cage-cart. When they drew near, they saw the prisoner was no other than Lu Zhi, the man they were going to help. Hastily dismounting, Liu Bei asked what had happened.

Lu Zhi explained, “I had surrounded the rebels and was on the point of smashing them, when Zhang Jue employed some of his supernatural powers and prevented my victory. The court sent down Eunuch Zhuo Feng to inquire into my failure, and that official demanded a bribe. I told him how hard pressed we were and asked him where, in the circumstances, I could find a gift for him. He went away in wrath and reported that I was hiding behind my ramparts and would not give battle and that I disheartened my army. So I was superseded by Dong Zhuo, and I have to go to the capital to answer the charge.”

This story put Zhang Fei into a rage. He was for slaying the escort and setting free Lu Zhi. But Liu Bei checked him.

“The government will take the due course,” said Liu Bei. “You must not act hastily!”

And the escort and the three brothers went two ways.

It was useless to continue on that road to Guangzong, so Guan Yu proposed to go back to Zhuo, and they retook the road. Two days later they heard the thunder of battle behind some hills. Hastening to the top, they beheld the government soldiers suffering great loss, and they saw the countryside was full of Yellow Scarves. On the rebels’ banners were the words Zhang Jue the Lord of Heaven written large.

“We will attack this Zhang Jue!” said Liu Bei to his brothers, and they galloped out to join in the battle.

Zhang Jue had worsted Dong Zhuo and was following up his advantage. He was in hot pursuit when the three brothers dashed into his army, threw his ranks into confusion, and drove him back fifteen miles. Then the brothers returned with the rescued general to his camp.

“What offices have you?” asked Dong Zhuo, when he had leisure to speak to the brothers.

“None,” replied they.

And Dong Zhuo treated them with disrespect. Liu Bei retired calmly, but Zhang Fei was furious.

“We have just rescued this menial in a bloody fight,” cried Zhang Fei, “and now he is rude to us! Nothing but his death can slake my anger.”

Zhang Fei stamped toward Dong Zhuo’s tent, holding firmly a sharp sword.

As it was in olden time so it is today,

The simple wight may merit well,

Officialdom holds sway;

Zhang Fei, the blunt and hasty,

Where can you find his peer?

But slaying the ungrateful would

Mean many deaths a year.

Dong Zhuo’s fate will be unrolled in later chapters.

Chapter 41

Liu Bei Leads His People Over The River; Zhao Zilong Rescues The Child Lord At Dangyang.

The last chapter closed with the attack made by Zhang Fei as soon as his brother had let loose the waters on the doomed army. He met with Xu Chu and a combat began, but a fight with such a warrior was not to Xu Chu’s taste and he ran away. Zhang Fei followed till he came upon Liu Bei and Zhuge Liang, and the three went upstream till they came to the boats that had been prepared by Liu Feng and Mi Fang, when they all crossed over and marched toward Fancheng. As soon as they disembarked, Zhuge Liang ordered the boats and rafts to be burned.

Cao Ren gathered in the remnants of his army and camped at Xinye, while his colleague Cao Hong went to tell their lord the evil tidings of defeat.

“How dare he, this rustic Zhuge Liang!” exclaimed Cao Cao angrily.

Cao Cao then hastily sent an overwhelming army to camp near the place and gave orders for enormous works against the city, leveling hills and turning rivers to launch a violent assault on Fancheng from every side at once.

Then Liu Ye came in to see his lord and said, “Sir, you are new to this region, and you should win over the people’s hearts. Liu Bei has moved all the people from Xinye to Fancheng. If we march through the country, the people will be ground to powder. It would be well to call upon Liu Bei first to surrender, which will prove to the people that you have a care for them. If he yields, then we get Jingzhou without fighting.”

Cao Cao agreed and asked who would be a suitable messenger. Liu Ye suggested Xu Shu.

“He is a close friend of Liu Bei, and he is here with the army,” said Liu Ye.

“But he will not come back,” objected Cao Cao.

“If he does not return, he will be a laughing stock to the whole world. He will come back.”

Xu Shu was sent for, and Cao Cao said, “My first intention was to level Fancheng with the ground. But out of pity for its people, you may carry an offer to Liu Bei that if he will surrender, he will not only not be punished but he shall be given rank. But if he holds on his present misguided course, the whole of his followers shall be destroyed. Now you are an honest man and so I confide this mission to you, and I trust you will not disappoint me.”

Xu Shu said nothing but accepted his orders and went to the city, where he was received by both Liu Bei and Zhuge Liang. They enjoyed a talk over old times before Xu Shu mentioned the object of his mission.

Then he said, “Cao Cao has sent me to invite you to surrender, thereby making a bid for popularity. But you ought also to know that he intends to attack the city from every point, that he is damming up the White River’s waters to be sent against you, and I fear you will not be able to hold the city. You ought to prepare.”

Liu Bei asked Xu Shu to remain with them, but Xu Shu said, “That is impossible, for all the world would ridicule me if I stayed. My old mother is dead, and I never forget my resentment. My body may be over there, but I swear never to form a plan for Cao Cao. You have the Sleeping Dragon to help you and need have no anxiety about the ultimate achievement of your undertaking. But I must go.”

And Xu Shu took his leave. Liu Bei felt he could not press his friend to stay. Xu Shu returned to Cao Cao’s camp and reported that Liu Bei had no intention of surrender. This angered Cao Cao who gave orders to begin the advance and siege.

When Liu Bei asked what Zhuge Liang meant to do, Zhuge Liang replied, “We shall abandon Fancheng and take Xiangyang.”

“But what of the people who have followed us? They cannot be abandoned.”

“You can tell them to do as they wish. They may come if they like, or remain here.”

They sent Guan Yu to prepare boats and told Sun Qian to proclaim to the people that Cao Cao was coming, that the city could not be defended, and those who wished to do so might cross the river with the army.

All the people cried, “We will follow the Prince even if it be to death!”

They started at once, some lamenting, some weeping, the young helping the aged, parents leading their children, the strong soldiers carrying the women. As the crowds crossed the river, from both banks arose the sound of lamentation.

Liu Bei was much affected as he saw all this from the boat.

“Why was I ever born,” said he, “to be the cause of all this misery to the people?”

He made to leap into the river, but they held him back. All were deeply sympathetic. When the boat reached the southern shore, he looked back at the weeping crowds waiting still on the other bank and was again moved to tears. He bade Guan Yu hasten the boats before he mounted and rode on.

When Xiangyang came in sight, they saw many flags flying on the walls and that the moat was protected by barbed barriers.

Liu Bei checked his horse and called out, “Liu Zong, good nephew! I only wish to save the people and nothing more. I pray you quickly open the gates.”

But Liu Zong was too frightened to appear. Cai Mao and Zhang Yun went up to one of the fighting towers and ordered the soldiers to shoot arrows down on those without the walls. The people gazed up at the towers and wept aloud.

Suddenly there appeared a general, with a small following, who cried out, “Cai Mao and Zhang Yun are two traitors. The princely Liu Bei is a most upright man and has come here to preserve his people. Why do you repulse him?”

All looked at this man. He was of eight-span height, with a face dark brown as a ripe date. He was from Yiyang and named Wei Yan. At that moment he looked very terrible, whirling his sword as if about to slice up the gate guards. They lost no time in throwing open the gate and dropping the bridge.

“Come in, Uncle Liu Bei,” cried Wei Yan, “and bring your army to slay these traitors!”

Zhang Fei plunged forward to take Cai Mao and Zhang Yun, but he was checked by his brother, who said, “Do not frighten the people!”

Thus Wei Yan let in Liu Bei. As soon as he entered, he saw a general galloping up with a few men.

The newcomer yelled, “Wei Yan, you nobody! How dare you create trouble? Do you not know me, General Wen Ping?”

Wei Yan turned angrily, set his spear, and galloped forward to attack the general. The soldiers joined in the fray and the noise of battle rose to the skies.

“I wanted to preserve the people, and I am only causing them injury,” cried Liu Bei distressed. “I do not wish to enter the city.”

“Jiangling is an important point. We will first take that as a place to dwell in,” said Zhuge Liang.

“That pleases me greatly,” said Liu Bei.

So they led the people thither and away from Xiangyang. Many of the inhabitants of that city took advantage of the confusion to escape, and they also joined themselves to Liu Bei.

Meanwhile, within the inhospitable city, Wei Yan and Wen Ping fought. The battle continued for four or five watches, all through the middle of the day, and nearly all the combatants fell. Then Wei Yan got away. As he could not find Liu Bei, he rode off to Changsha and sought an asylum with Governor Han Xuan.

Liu Bei wandered away from the city of Xiangyang that had refused shelter. Soldiers and people, his following numbered more than a hundred thousand. The carts numbered scores of thousands, and the burden bearers were innumerable. Their road led them past the tomb of Liu Biao, and Liu Bei turned aside to bow at the grave.

He lamented, saying, “Shameful is thy brother, lacking both in virtue and in talents. I refused to bear the burden you wished to lay upon me, wherein I was wrong. But the people committed no sin. I pray your glorious spirit descend and rescue these people.”

His prayer was fraught with sorrow, and all those about him wept.

Just then a scout rode up with the news that Fancheng was already taken by Cao Cao and that his army were preparing boats and rafts to cross the river.

The generals of Liu Bei said, “Jiangling is a defensible shelter, but with this crowd we can only advance very slowly, and when can we reach the city? If Cao Cao pursue, we shall be in a parlous state. Our counsel is to leave the people to their fate for a time and press on to Jiangling.”

But Liu Bei wept, saying, “The success of every great enterprise depends upon humanity. How can I abandon these people who have joined me?”

Those who heard him repeat this noble sentiment were greatly affected.

In time of stress his heart was tender toward the people,

And he wept as he went down into the ship,

Moving the hearts of soldiers to sympathy.

Even today, in the countryside,

Fathers and elders recall the Princely One’s kindness.

The progress of Liu Bei, with the crowd of people in his train, was very slow.

“The pursuers will be upon us quickly,” said Zhuge Liang. “Let us send Guan Yu to Jiangxia for succor. Liu Qi should be told to bring soldiers and prepare boats for us at Jiangling.”

Liu Bei agreed to this and wrote a letter which he sent by the hands of Guan Yu and Sun Qian and five hundred troops. Zhang Fei was put in command of the rear guard. Zhao Zilong was told to guard Liu Bei’s family, while the others ordered the march of the people.

They only traveled three or four miles daily and the halts were frequent.

Meanwhile Cao Cao was at Fancheng, whence he sent troops over the river toward Xiangyang. He summoned Liu Zong, but Liu Zong was too afraid to answer the call. No persuasion could get him to go.

Wang Wei said to him privately, “Now you can overcome Cao Cao if you are wise. Since you have announced surrender and Liu Bei has gone away, Cao Cao will relax his precautions, and you can catch him unawares. Send a well-prepared but unexpected force to waylay him in some commanding position, and the thing is done. If you were to take Cao Cao prisoner, your fame would run throughout the empire, and the land would be yours for the taking. This is a sort of opportunity that does not recur, and you should not miss it.”

The young man consulted Cai Mao, who called Wang Wei an evil counselor and spoke to him harshly.

“You are mad! You know nothing and understand nothing of destiny,” said Cai Mao.

Wang Wei angrily retorted, saying, “Cai Mao is the betrayer of the country, and I wish I could eat him alive!”

The quarrel waxed deadly, and Cai Mao wanted to slay Wang Wei. But eventually peace was restored by Kuai Yue.

Then Cai Mao and Zhang Yun went to Fancheng to see Cao Cao.

Cai Mao was by instinct specious and flattering, and when his host asked concerning the resources of Jingzhou, he replied, “There are fifty thousand of horse, one hundred fifty thousand of foot, and eighty thousand of marines. Most of the money and grain are at Jiangling. The rest is stored at various places. There are ample supplies for a year.”

“How many war vessels are there? Who is in command?” said Cao Cao.

“The ships, of all sizes, number seven thousands, and we two are the commanders.”

Upon this Cao Cao conferred upon Cai Mao the title of the Lord Who Controls the South, and Supreme Admiral of the Naval Force; and Zhang Yun was his Vice-Admiral with the title of the Lord Who Brings Obedience.

When they went to thank Cao Cao for these honors, he told them, saying, “I am about to propose to the Throne that Liu Biao’s son should be perpetual Imperial Protector of Jingzhou in succession to his late father.”

With this promise for their young master and the honors for themselves, they retired.

Then Xun You asked Cao Cao, “Why these two evident self-seekers and flatterers have been treated so generously?”

Cao Cao replied, “Do I not know all about them? Only in the north, where we have been, we know very little of war by water, and these two men do. I want their help for the present. When my end is achieved, I can do as I like with them.”

Liu Zong was highly delighted when his two chief supporters returned with the promise Cao Cao had given them. Soon after he gave up his seal and military commission and proceeded to welcome Cao Cao, who received him very graciously.

Cao Cao next proceeded to camp near Xiangyang. The populace, led by Cai Mao and Zhang Yun, welcomed him with burning incense, and he on his part put forth proclamations couched in comforting terms.

Cao Cao presently entered the city and took his seat in the residence in state. Then he summoned Kuai Yue and said to him graciously, “I do not rejoice so much at gaining Jingzhou as at meeting you, friend Kuai Yue.”

Cao Cao made Kuai Yue Governor of Jiangling and Lord of Fancheng; Wang Can, Fu Xuan, and Kuai Yue’s other adherents were all ennobled. Liu Zong became Imperial Protector of Qingzhou in the north and was ordered to proceed to his region forthwith.

Liu Zong was greatly frightened and said, “I have no wish to become an actual official. I wish to remain in the place where my father and mother live.”

Said Cao Cao, “Your protectorship is quite near the capital, and I have sent you there as a full official to remove you from the intrigues of this place.”

In vain Liu Zong declined the honors thus thrust upon him: He was compelled to go and he departed, taking his mother with him. Of his friends, only Wang Wei accompanied him. Some of his late officers escorted him as far as the river and then took their leave.

Then Cao Cao called his trusty officer Yu Jin and said, “Follow Liu Zong and put him and his mother to death. Our worries are thus removed.”

Yu Jin followed the small party.

When he drew near he shouted, “I have an order from the great Prime Minister to put you both to death, mother and son! You may as well submit quietly.”

Lady Cai threw her arms about her son, lifted up her voice and wept. Yu Jin bade his soldiers get on with their bloody work. Only Wang Wei made any attempt to save his mistress, and he was soon killed. The two, mother and son, were soon finished, and Yu Jin returned to report his success. He was richly rewarded.

Next Cao Cao sent to discover and seize the family of Zhuge Liang, but they had already disappeared. Zhuge Liang had moved them to the Three Gorges. It was much to Cao Cao’s disgust that the search was fruitless.

So Xiangyang was settled. Then Xun You proposed a further advance.

He said, “Jiangling is an important place, and very rich. If Liu Bei gets it, it will be difficult to dislodge him.”

“How could I have overlooked that?” said Cao Cao.

Then he called upon the officers of Xiangyang for one who could lead the way. They all came except Wen Ping.

Cao Cao sent for him and soon he came also.

“Why are you late?” asked Cao Cao.

Wen Ping said, “To be a minister and see one’s master lose his own boundaries is most shameful. Such a person has no face to show to anyone else, and I was too ashamed to come.”

His tears fell fast as he finished this speech. Cao Cao admired his loyal conduct and rewarded him with office of Governorship of Jiangxia and a title of Lordship, and also bade him open the way.

The spies returned and said, “Liu Bei is hampered by the crowds of people who have followed him. He can proceed only three or four miles daily, and he is only one hundred miles away.”

Cao Cao decided to take advantage of Liu Bei’s plight, so he chose out five thousand of tried horsemen and sent them after the cavalcade, giving them a limit of a day and a night to come up therewith. The main army would follow.

As has been said Liu Bei was traveling with a huge multitude of followers, to guard whom he had taken what precautions were possible. Zhang Fei was in charge of the rear guard, and Zhao Zilong was to protect his lord’s family. Guan Yu had been sent to Jiangxia.

One day Zhuge Liang came in and said, “There is as yet no news from Jiangxia. There must be some difficulties.”

“I wish that you yourself would go there,” said Liu Bei. “Liu Qi would remember your former kindness to him and consent to anything you proposed.”

Zhuge Liang said he would go and set out with Liu Feng, the adopted son of Liu Bei, taking an escort of five hundred troops.

A few days after, while on the march in company with three of his commanders—Jian Yong, Mi Zhu, and Mi Fang—a sudden whirlwind rose just in front of Liu Bei, and a huge column of dust shot up into the air hiding the face of the sun.

Liu Bei was frightened and asked, “What might that portend?”

Jian Yong, who knew something of the mysteries of nature, took the auspices by counting secretly on his fingers.

Pale and trembling, he announced, “A calamity is threatening this very night. My lord must leave the people to their fate and flee quickly.”

“I cannot do that,” said Liu Bei.

“If you allow your pity to overcome your judgment, then misfortune is very near,” said Jian Yong.

Thus spoke Jian Yong to his lord, who then asked what place was near.

His people replied, “Dangyang is quite close, and there is a very famous mountain near it called Prospect Mountain.”

Then Liu Bei bade them lead the way thither.

The season was late autumn, just changing to winter, and the icy wind penetrated to the very bones. As evening fell, long-drawn howls of misery were heard on every side. At the middle of the fourth watch, two hours after midnight, they heard a rumbling sound in the northwest. Liu Bei halted and placed himself at the head of his own guard of two thousand soldiers to meet whatever might come.

Presently Cao Cao’s men appeared and made fierce onslaught. Defense was impossible, though Liu Bei fought desperately. By good fortune just at the crisis Zhang Fei came up, cut an alley through, rescued his brother, and got him away to the east. Presently they were stopped by Wen Ping.

“Turncoat! Can you still look humans in the face?” cried Liu Bei.

Wen Ping was overwhelmed with shame and led his troops away. Zhang Fei, now fighting, protected his brother till dawn.

By that time Liu Bei had got beyond the sound of battle, and there was time to rest. Only a few of his followers had been able to keep near him. He knew nothing of the fate of his officers or the people.

He lifted up his voice in lamentation, saying, “Myriads of living souls are suffering from love of me, and my officers and my loved ones are lost. One would be a graven image not to weep at such loss!”

Still plunged in sadness, presently he saw hurrying toward him Mi Fang, with an enemy’s arrow still sticking in his face.

Mi Fang exclaimed, “Zhao Zilong has gone over to Cao Cao!”

Liu Bei angrily bade him be silent, crying, “Do you think I can believe that of my old friend?”

“Perhaps he has gone over,” said Zhang Fei. “He must see that we are nearly lost and there are riches and honors on the other side.”

“He has followed me faithfully through all my misfortunes. His heart is firm as a rock. No riches or honors would move him,” said Liu Bei.

“I saw him go away northwest,” said Mi Fang.

“Wait till I meet him,” said Zhang Fei. “If I run against him, I will kill him!”

“Beware how you doubt him,” said Liu Bei. “Have you forgotten the circumstances under which your brother Guan Yu had to slay Cai Yang to ease your doubts of him? Zhao Zilong’s absence is due to good reason wherever he has gone, and he would never abandon me.”

But Zhang Fei was not convinced. Then he, with a score of his men, rode to the Long Slope Bridge. Seeing a wood near the bridge, an idea suddenly struck him. He bade his followers cut branches from the trees, tie them to the tails of the horses, and ride to and fro so as to raise a great dust as though an army were concealed in the wood. He himself took up his station on the bridge facing the west with spear set ready for action. So he kept watch.

Now Zhao Zilong, after fighting with the enemy from the fourth watch till daylight, could see no sign of his lord and, moreover, had lost his lord’s family.

He thought bitterly within himself, “My master confided to me his family and the child lord Liu Shan; and I have lost them. How can I look him in the face? I can only go now and fight to the death. Whatever happen, I must go to seek the women and my lord’s son.”

Turning about he found he had but some forty followers left. He rode quickly to and fro among the scattered soldiers seeking the lost women. The lamentations of the people about him were enough to make heaven and earth weep. Some had been wounded by arrows, others by spears; they had thrown away their children, abandoned their wives, and were flying they knew not whither in crowds.

Presently Zhao Zilong saw a man lying in the grass and recognized him as Jian Yong.

“Have you seen the two mothers?” cried he.

Jian Yong replied, “They left their carriage and ran away taking the child lord Liu Shan in their arms. I followed but on the slope of the hill I was wounded and fell from my horse. The horse was stolen. I could fight no longer, and I lay down here.”

Zhao Zilong put his colleague on the horse of one of his followers, told off two soldiers to support Jian Yong, and bade Jian Yong ride to their lord and tell him of the loss.

“Say,” said Zhao Zilong, “that I will seek the lost ones in heaven or hell, through good or evil. And if I find them not, I will die in the battlefield.”

Then Zhao Zilong rode off toward the Long Slope Bridge.

As he went, a voice called out, “General Zhao Zilong, where are you going?”

“Who are you?” said Zhao Zilong, pulling up.

“One of the Princely One’s carriage guards. I am wounded.”

“Do you know anything of the two ladies?”

“Not very long ago I saw Lady Gan go south with a party of other women. Her hair was down, and she was barefooted”

Hearing this, without even another glance at the speaker, Zhao Zilong put his horse at full gallop toward the south. Soon he saw a small crowd of people, male and female, walking hand in hand.

“Is Lady Gan among you!” he called out.

A woman in the rear of the party looked up at him and uttered a loud cry.

He slipped off his steed, stuck his spear in the sand, and wept, “It was my fault that you were lost. But where are Lady Mi and our child lord?”

Lady Gan replied, “She and I were forced to abandon our carriage and mingle with the crowd on foot. Then a band of soldiers came up, and we were separated. I do not know where they are. I ran for my life.”

As she spoke, a howl of distress rose from the crowd of fugitives, for a thousand of soldiers appeared. Zhao Zilong recovered his spear and mounted ready for action. Presently he saw among the soldiers a prisoner bound upon a horse, and the prisoner was Mi Zhu. Behind Mi Zhu followed a general gripping a huge sword. The troops belonged to the army of Cao Ren, and the general was Chunyu Dao. Having captured Mi Zhu, he was just taking him to his chief as a proof of his prowess.

Zhao Zilong shouted and rode at the captor who was speedily slain by a spear thrust and his captive was set free. Then taking two of the horses, Zhao Zilong set Lady Gan on one and Mi Zhu took the other. They rode away toward Long Slope Bridge.

But there, standing grim on the bridge, was Zhang Fei.

As soon as he saw Zhao Zilong, he called out, “Zhao Zilong, why have you betrayed our lord?”

“I fell behind because I was seeking the ladies and our child lord,” said Zhao Zilong. “What do you mean by talking of betrayal?”

“If it had not been that Jian Yong arrived before you and told me the story, I should hardly have spared you.”

“Where is the master?” said Zhao Zilong.

“Not far away, in front there,” said Zhang Fei.

“Conduct Lady Gan to him. I am going to look for Lady Mi,” said Zhao Zilong to his companion, and he turned back along the road by which he had come.

Before long he met a leader armed with an iron spear and carrying a sword slung across his back, riding a curvetting steed, and leading ten other horsemen. Without uttering a word Zhao Zilong rode straight toward him and engaged. At the first pass Zhao Zilong disarmed his opponent and brought him to earth. His followers galloped away.

This fallen officer was no other than Xiahou En, Cao Cao’s sword-bearer. And the sword on Xiahou En’s back was his master’s . Cao Cao had two swords, one called “Trust of God” and the other “Blue Blade”. Trust of God was the weapon Cao Cao usually wore at his side, the other being carried by his sword-bearer. The Blue Blade would cut clean through iron as though it were mud, and no sword had so keen an edge.

Before Zhao Zilong thus fell in with Xiahou En, the latter was simply plundering, depending upon the authority implied by his office. Least of all thought he of such sudden death as met he at Zhao Zilong’s hands.

So Zhao Zilong got possession of a famous sword. The name Blue Blade was chased in gold characters so that he recognized its value at once. He stuck it in his belt and again plunged into the press. Just as he did so, he turned his head and saw he had not a single follower left. He was quite alone.

Nevertheless not for a single instant thought he of turning back. He was too intent upon his quest. To and fro, back and forth, he rode questioning this person and that.

At length a man said, “A woman with a child in her arms, and wounded in the thigh so that she cannot walk, is lying over there through that hole in the wall.”

Zhao Zilong rode to look and there, beside an old well behind the broken wall of a burned house, sat the mother clasping the child to her breast and weeping.

Zhao Zilong was on his knees before her in a moment.

“My child will live then since you are here,” cried Lady Mi. “Pity him, O General! Protect him, for he is the only son of his father’s flesh and blood. Take him to his father, and I can die content.”

“It is my fault that you have suffered,” replied Zhao Zilong. “But it is useless to say more. I pray you take my horse, while I will walk beside and protect you till we get clear.”

She replied, “I may not do that. What would you do without a steed? But the boy here I confide to your care. I am badly wounded and cannot hope to live. Pray take him and go your way. Do not trouble more about me.”

“I hear shouting,” said Zhao Zilong. “The soldiers will be upon us again in a moment. Pray mount quickly!”

“But really I cannot move,” she said. “Do not let there be a double loss!”

And she held out the child toward him as she spoke.

“Take the child!” cried Lady Mi. “His life and safety are in your hands.”

Again and again Zhao Zilong besought her to get on his horse, but she would not.

The shouting drew nearer and nearer, Zhao Zilong spoke harshly, saying, “If you will not do what I say, what will happen when the soldiers come up?”

She said no more. Throwing the child on the ground, she turned over and threw herself into the old well. And there she perished.

The warrior relies upon the strength of his charger,

Afoot, how could he bear to safety his young prince?

Brave mother! Who died to preserve the son of her husband’s line;

Heroine was she, bold and decisive!

Seeing that Lady Mi had resolved the question by dying, there was nothing more to be done. Zhao Zilong pushed over the wall to fill the well, and thus making a grave for the lady. Then he loosened his armor, let down the heart-protecting mirror, and placed the child in his breast. This done he slung his spear and remounted.

Zhao Zilong had gone but a short distance, when he saw a horde of enemy led by Yan Ming, one of Cao Hong’s generals. This warrior used a double edged, three pointed weapon and he offered battle. However, Zhao Zilong disposed of him after a very few bouts and dispersed his troops.

As the road cleared before him, Zhao Zilong saw another detachment barring his way. At the head of this was a general exalted enough to display a banner with his name Zhang He of Hejian. Zhao Zilong never waited to parley but attacked. However, this was a more formidable antagonist, and half a score bouts found neither any nearer defeat. But Zhao Zilong, with the child in his bosom, could only fight with the greatest caution, and so he decided to flee.

Zhang He pursued, and as Zhao Zilong thought only of thrashing his steed to get away, and little of the road, suddenly he went crashing into a pit. On came his pursuer, spear at poise. Suddenly a brilliant flash of light seemed to shoot out of the pit, and the fallen horse leapt with it into the air and was again on firm earth.

A bright glory surrounds the child of the imperial line, now in danger,

The powerful charger forces his way through the press of battle,

Bearing to safety him who was destined to the throne two score years and two;

And the general thus manifested his godlike courage.

This apparition frightened Zhang He, who abandoned the pursuit forthwith, and Zhao Zilong rode off.

Presently he heard shouts behind, “Zhao Zilong, Zhao Zilong, stop!” and at the same time he saw ahead of him two generals who seemed disposed to dispute his way.

Ma Yan and Zhang Zi following and Jiao Chu and Zhang Neng in front, his state seemed desperate, but Zhao Zilong quailed not.

As the men of Cao Cao came pressing on, Zhao Zilong drew Cao Cao’s own sword to beat them off. Nothing could resist the blue blade sword. Armor, clothing, it went through without effort and blood gushed forth in fountains wherever it struck. So the four generals were soon beaten off, and Zhao Zilong was once again free.

Now Cao Cao from a hilltop of the Prospect Mountain saw these deeds of derring-do and a general showing such valor that none could withstand him, so Cao Cao asked of his followers whether any knew the man. No one recognized him.

So Cao Hong galloped down into the plain and shouted out, “We should hear the name of the warrior!”

“I am Zhao Zilong of Changshan!” replied Zhao Zilong.

Cao Hong returned and told his lord, who said, “A very tiger of a leader! I must get him alive.”

Whereupon he sent horsemen to all detachments with orders that no arrows were to be fired from an ambush at any point Zhao Zilong should pass: He was to be taken alive.

And so Zhao Zilong escaped most imminent danger, and Liu Shan’s safety, bound up with his savior’s, was also secured. On this career of slaughter which ended in safety, Zhao Zilong, bearing in his bosom the child lord Liu Shan, cut down two main banners, took three spears, and slew or wounded of Cao Cao’s generals half a hundred, all men of renown.

Blood dyed the fighting robe and crimsoned his buff coat;

None dared engage the terrible warrior at Dangyang;

In the days of old lived the brave Zhao Zilong,

Who fought in the battlefield for his lord in danger.

Having thus fought his way out of the press, Zhao Zilong lost no time in getting away from the battle field. His white battle robe had turned red, soaking in blood.

On his way, near the rise of the hills, he met with two other bodies of troops under two brothers, Zhong Jin and Zhong Shen. One of these was armed with a massive ax, the other a halberd.

As soon as they saw Zhao Zilong, they knew him and shouted, “Quickly dismount and be bound!”

He has only escaped from the tiger cave,

To risk the dragon pool’s sounding wave.

How Zhao Zilong escaped will be next related.

Chapter 42

Screaming Zhang Fei Triumphs At Long Slope Bridge; Defeated Liu Bei Marches To Hanjin.

As related in the last chapter two generals appeared in front of Zhao Zilong, who rode at them with his spear ready for a thrust. Zhong Jin was leading, flourishing his battle-ax. Zhao Zilong engaged and very soon unhorsed him. Then Zhao Zilong galloped away. Zhong Shen rode up behind ready with his halberd, and his horse’s nose got so close to the other’s tail that Zhao Zilong could see in his armor the reflection of the play of Zhong Shen’s weapon. Then suddenly, and without warning, Zhao Zilong wheeled round his horse so that he faced his pursuer, and their two steeds struck breast to breast. With his spear in his left hand, Zhao Zilong warded off the halberd strokes, and in his right he swung the blue blade sword. One slash and he had cut through both helmet and head. Zhong Shen fell to the ground, a corpse with only half a head on his body. His followers fled, and Zhao Zilong retook the road toward Long Slope Bridge.

But in his rear arose another tumultuous shouting, seeming to rend the very sky, and Wen Ping came up behind. However, although the man was weary and his steed spent, Zhao Zilong got close to the bridge where he saw standing, all ready for any fray, Zhang Fei.

“Help me, Zhang Fei!” he cried and crossed the bridge.

“Hasten!” cried Zhang Fei, “I will keep back the pursuers!”

About seven miles from the bridge, Zhao Zilong saw Liu Bei with his followers reposing in the shade of some trees. He dismounted and drew near, weeping. The tears also started to Liu Bei’s eyes when he saw his commander.

Still panting from his exertions, Zhao Zilong gasped out, “My fault—death is too light a punishment. Lady Mi was severely wounded. She refused my horse and threw herself into a well. She is dead, and all I could do was to fill in the well with the rubbish that lay around. But I placed the babe in the breast of my fighting robe and have won my way out of the press of battle. Thanks to the little lord’s grand luck I have escaped. At first he cried a good deal, but for some time now he has not stirred or made a sound. I fear I may not have saved his life after all.”

Then Zhao Zilong opened his robe and looked: The child was fast asleep.

“Happily, Sir, your son is unhurt,” said Zhao Zilong as he drew him forth and presented him in both hands.

Liu Bei took the child but threw it aside angrily, saying, “To preserve that suckling I very nearly lost a great general!”

Zhao Zilong picked up the child again and, weeping, said, “Were I ground to powder, I could not prove my gratitude.”

From out Cao Cao’s host a tiger rushed,

His wish but to destroy;

Though Liu Bei’s consort lost her life,

Zhao Zilong preserved her boy.

“Too great the risk you ran to save

This child,” the father cried.

To show he rated Zhao Zilong high,

He threw his son aside.

Wen Ping and his company pursued Zhao Zilong till they saw Zhang Fei’s bristling mustache and fiercely glaring eyes before them. There he was seated on his battle steed, his hand grasping his terrible serpent spear, guarding the bridge. They also saw great clouds of dust rising above the trees and concluded they would fall into an ambush if they ventured across the bridge. So they stopped the pursuit, not daring to advance further.

In a little time Cao Ren, Xiahou Dun, Xiahou Yuan, Li Dian, Yue Jing, Zhang Liao, Xu Chu, Zhang He, and other generals of Cao Cao came up, but none dared advance, frightened not only by Zhang Fei’s fierce look, but lest they should become victims of a ruse of Zhuge Liang. As they came up, they formed a line on the west side, halting till they could inform their lord of the position.

As soon as the messengers arrived and Cao Cao heard about it, he mounted and rode to the bridge to see for himself. Zhang Fei’s fierce eye scanning the hinder position of the army opposite him saw the silken umbrella, the axes and banners coming along, and concluded that Cao Cao came to see for himself how matters stood.

So in a mighty voice he shouted: “I am Zhang Fei of Yan. Who dares fight with me?”

At the sound of this thunderous voice, a terrible quaking fear seized upon Cao Cao, and he bade them take the umbrella away.

Turning to his followers, he said, “Guan Yu had said that his brother Zhang Fei was the sort of man to go through an army of a hundred legions and take the head of its commander-in-chief, and do it easily. Now here is this terror in front of us, and we must be careful.”

As he finished speaking, again that terrible voice was heard, “I am Zhang Fei of Yan.Who dares fight with me?”

Cao Cao, seeing his enemy so fierce and resolute, was too frightened to think of anything but retreat.

Zhang Fei, seeing a movement going on in the rear, once again shook his spear and roared, “What mean you? You will not fight nor do you run away!”

This roar had scarcely begun when one of Cao Cao’s staff, Xiahou Jie, reeled and fell from his horse terror-stricken, paralyzed with fear. The panic touched Cao Cao and spread to his whole surroundings, and he and his staff galloped for their lives. They were as frightened as a suckling babe at a clap of thunder or a weak woodcutter at the roar of a tiger. Many threw away their spears, dropped their casques and fled, a wave of panic-stricken humanity, a tumbling mass of terrified horses. None thought of ought but flight, and those who ran trampled the bodies of fallen comrades under foot.

Zhang Fei was wrathful; and who dared

To accept his challenge? Fierce he glared;

His thunderous voice rolled out, and then

In terror fled Cao Cao’s armed soldiers.

Panic-stricken Cao Cao galloped westward with the rest, thinking of nothing but getting away. He lost his headdress, and his loosened hair streamed behind him. Presently Zhang Liao and Xu Chu came up with him and seized his bridle; fear had deprived him of all self-control.

“Do not be frightened,” said Zhang Liao. “After all Zhang Fei is but one man and not worthy of extravagant fear. If you will only return and attack, you will capture your enemy.”

That time Cao Cao had somewhat overcome his panic and become reasonable. Two generals were ordered back to the bridge to reconnoiter.

Zhang Fei saw the disorderly rout of the enemy but he dared not pursue. However, he bade his score or so of dust-raising followers to cut loose the branches from their horses’ tails and come to help destroy the bridge. This done he went to report to his brother and told him of the destruction of the bridge.

“Brave as you are, brother, and no one is braver, but you are no strategist,” said Liu Bei.

“What mean you, brother?”

“Cao Cao is very deep. You are no match for him. The destruction of the bridge will bring him in pursuit.”

“If he ran away at a yell of mine, think you he will dare return?”

“If you had left the bridge, he would have thought there was an ambush and would not have dared to pass it. Now the destruction of the bridge tells him we are weak and fearful, and he will pursue. He does not mind a broken bridge. His legions could fill up the biggest rivers that we could get across.”

So orders were given to march, and they went by a bye-road which led diagonally to Hanjin by the road of Minyang.

The two generals sent by Cao Cao to reconnoiter near Long Slope Bridge returned, saying, “The bridge has been destroyed. Zhang Fei has left.”

“Then he is afraid,” said Cao Cao.

Cao Cao at once gave orders to set ten thousand men at work on three floating bridges to be finished that night.

Li Dian said, “I fear this is one of the wiles of Zhuge Liang. So be careful.”

“Zhang Fei is just a bold warrior, but there is no guile about him,” said Cao Cao.

He gave orders for immediate advance.

Liu Bei was making all speed to Hanjin. Suddenly there appeared in his track a great cloud of dust whence came loud rolls of drums and shoutings.

Liu Bei was dismayed and said, “Before us rolls the Great River; behind is the pursuer. What hope is there for us?”

But he bade Zhao Zilong organize a defense.

Now Cao Cao in an order to his army had said, “Liu Bei is a fish in the fish kettle, a tiger in the pit. Catch him this time, or the fish will get back to the sea and the tiger escape to the mountains. Therefore every general must use his best efforts to press on.”

In consequence every leader bade those under him hasten forward. And they were pressing on at great speed, when suddenly a body of soldiers appeared from the hills and a voice cried, “I have waited here a long time!”

The leader who had shouted this bore in his hand the green-dragon saber and rode Red Hare, for indeed it was no other than Guan Yu. He had gone to Jiangxia for help and had returned with a whole legion of ten thousand. Having heard of the battle, he had taken this very road to intercept pursuit.

As soon as Guan Yu appeared, Cao Cao stopped and said to his officers, “Here we are, tricked again by that Zhuge Liang!”

Without more ado he ordered a retreat. Guan Yu followed him some three miles and then drew off to act as guard to his elder brother on his way to the river. There boats were ready, and Liu Bei and family went on board. When all were settled comfortably in the boat, Guan Yu asked where was his sister, the second wife of his brother, Lady Mi. Then Liu Bei told him the story of Dangyang.

“Alas!” said Guan Yu. “Had you taken my advice that day of the hunting in Xutian, we should have escaped the misery of this day.”

“But,” said Liu Bei, “on that day it was ‘Ware damaged when pelting rats.’”

Just as Liu Bei spoke, he heard war drums on the south bank. A fleet of boats, thick as a flight of ants, came running up with swelling sails before the fair wind. He was alarmed.

The boats came nearer. There Liu Bei saw the white clad figure of a man wearing a silver helmet who stood in the prow of the foremost ship.

The leader cried, “Are you all right, my uncle? I am very guilty.”

It was Liu Qi. He bowed low as the ship passed, saying, “I heard you were in danger from Cao Cao, and I have come to aid you.”

Liu Bei welcomed Liu Qi with joy, and his soldiers joined in with the main body, and the whole fleet sailed on, while they told each other their adventures.

Unexpectedly in the southwest there appeared a line of fighting ships swishing up before a fair wind.

Liu Qi said, “All my troops are here, and now there is an enemy barring the way. If they are not Cao Cao’s ships, they must be from the South Land. We have a poor chance. What now?”

Liu Bei went to the prow and gazed at them. Presently he made out a figure in a turban and Daoist robe sitting in the bows of one of the boats and knew it to be Zhuge Liang. Behind him stood Sun Qian.

When they were quite near, Liu Bei asked Zhuge Liang how he came to be there.

And Zhuge Liang reported what he had done, saying, “When I reached Jiangxia, I sent Guan Yu to land at Hanjin with reinforcements, for I feared pursuit from Cao Cao and knew that road you would take instead of Jiangling. So I prayed your nephew to go to meet you, while I went to Xiakou to muster as many soldiers as possible.”

The new-comers added to their strength, and they began once more to consider how their powerful enemy might be overcome.

Said Zhuge Liang, “Xiakou is strong and a good strategic point. It is also rich and suited for a lengthy stay. I would ask you, my lord, to make it a permanent camp. Your nephew can go to Jiangxia to get the fleet in order and prepare weapons. Thus we can create two threatening angles for our position. If we all return to Jiangxia, the position will be weakened.”

Liu Qi replied, “The Directing Instructor’s words are excellent, but I wish rather my uncle stayed awhile in Jiangxia till the army was in thorough order. Then he could go to Xiakou.”

“You speak to the point, nephew,” replied Liu Bei.

Then leaving Guan Yu with five thousand troops at Xiakou he, with Zhuge Liang and his nephew, went to Jiangxia.

When Cao Cao saw Guan Yu with a force ready to attack, he feared lest a greater number were hidden away behind, so he stopped the pursuit. He also feared lest Liu Bei should take Jiangling, so he marched thither with all haste.

The two officers in command at Jingzhou City, Deng Yi and Liu Xin, had heard of the death of their lord Liu Zong at Xiangyang and, knowing that there was no chance of successful defense against Cao Cao’s armies, they led out the people of Jingzhou to the outskirts and offered submission. Cao Cao entered the city and, after restoring order and confidence, he released Han Song and gave him the dignified office of Director of Ambassadorial Receptions. He rewarded the others.

Then said Cao Cao, “Liu Bei has gone to Jiangxia and may ally himself with the South Land, and the opposition to me will be greater. Can he be destroyed?”

Xun You said, “The splendor of your achievements has spread wide. Therefore you might send a messenger to invite Sun Quan to a grand hunting party at Jiangxia, and you two could seize Liu Bei, share Jingzhou with Sun Quan, and make a solemn treaty. Sun Quan will be too frightened not to come over to you, and your end will be gained.”

Cao Cao agreed. He sent the letters by a messenger, and he prepared his army—horse and foot and marines. He had in all eight hundred thirty thousand troops, but he called them a million. The attack was to be by land and water at the same time.

The fleet advanced up the river in two lines. On the west it extended to Jingxia, on the east to Qichun. The stockades stretched one hundred miles.

The story of Cao Cao’s movements and successes reached Sun Quan, then in camp at Chaisang. He assembled his strategists to decide on a scheme of defense.

Lu Su said, “Jingzhou is contiguous to our borders. It is strong and defensive, its people are rich. It is the sort of country that an emperor or a king should have. Liu Biao’s recent death gives an excuse for me to be sent to convey condolence and, once there, I shall be able to talk over Liu Bei and the officers of the late Imperial Protector to combine with you against Cao Cao. If Liu Bei does as I wish, then success is yours.”

Sun Quan thought this a good plan, so he had the necessary letters prepared, and the gifts, and sent Lu Su with them.

All this time Liu Bei was at Jiangxia where, with Zhuge Liang and Liu Qi, he was endeavoring to evolve a good plan of campaign.

Zhuge Liang said, “Cao Cao’s power is too great for us to cope with. Let us go over to the South Land and ask help from Sun Quan. If we can set north and south at grips, we ought to be able to get some advantage from our intermediate position between them.”

“But will they be willing to have anything to do with us?” said Liu Bei. “The South Land is a large and populous country, and Sun Quan has ambitions of his own.”

Zhuge Liang replied, “Cao Cao with his army of a million holds the Han River and a half of the Great River. The South Land will certainly send to find out all possible about the position. Should any messenger come, I shall borrow a little boat and make a little trip over the river and trust to my little lithe tongue to set north and south at each other’s throats. If the south wins, we will assist in destroying Cao Cao in order to get Jingzhou. If the north wins, we shall profit by the victory to get the South Land. So we shall get some advantage either way.”

“That is a very fine view to take,” said Liu Bei. “But how are you going to get hold of anyone from the South Land to talk to?”

Liu Bei’s question was answered by the arrival of Lu Su, and as the ship touched the bank and the envoy came ashore, Zhuge Liang laughed, saying, “It is done!”

Turning to Liu Qi he asked, “When Sun Ce died, did your country send any condolences?”

“It is impossible there would be any mourning courtesies between them and us. We had caused the death of his father, Sun Jian.”

“Then it is certain that this envoy does not come to present condolences but to spy out the land.”

So he said to Liu Bei, “When Lu Su asks about the movements of Cao Cao, you will know nothing. If he presses the matter, say he can ask me.”

Having thus prepared their scheme, they sent to welcome the envoy, who entered the city in mourning garb. The gifts having been accepted, Liu Qi asked Lu Su to meet Liu Bei. When the introductory ceremonies were over, the three men went to one of the inner chambers to drink a cup of wine.

Presently Lu Su said to Liu Bei, “By reputation I have known you a long time, Uncle Liu Bei, but till today I have not met you. I am very gratified at seeing you. You have been fighting Cao Cao, though, lately, so I suppose you know all about him. Has he really so great an army? How many, do you think, he has?”

“My army was so small that we fled whenever we heard of his approach. So I do not know how many he had.”

“You had the advice of Zhuge Liang, and you used fire on Cao Cao twice. You burned him almost to death so that you can hardly say you know nothing about his soldiers,” said Lu Su.

“Without asking my adviser, I really do not know the details.”

“Where is Zhuge Liang? I should like to see him,” said Lu Su.

So they sent for him, and he was introduced.

When the ceremonies were over, Lu Su said, “I have long admired your genius but have never been fortunate enough to meet you. Now that I have met you, I hope I may speak of present politics.”

Replied Zhuge Liang, “I know all Cao Cao’s infamies and wickednesses, but to my regret we were not strong enough to withstand him. That is why we avoided him.”

“Is the Imperial Uncle going to stay here?”

“The Princely One is an old friend of Wu Ju, Governor of Changwu, and intends to go to him.”

“Wu Ju has few troops and insufficient supplies. He cannot ensure safety for himself. How can he receive the Uncle?” said Lu Su.

“Changwu is not one to remain in long, but it is good enough for the present. We can make other plans for the future.”