Aw-Aw-Tam Indian Nights: The Myths and Legends of the Pimas

Compiled by J. William Lloyd (1857-1940 C.E.)

Published in 1911 C.E.

Pima (Native America)

The Pima are North American Indians who traditionally lived along the Gila and Salt rivers in Arizona, U.S., which was the location of the Hohokam culture (200 to 1400 C.E.). Pima Indians call themselves the “River People,” speak a Uto-Aztecan language, and are usually considered to be the descendants of the Hohokam whose settle- ments were abandoned probably because of the Great Drought (1276-99) and the subsequent sparse and unpredict- able rainfall that lasted until 1450. The Pima were traditionally sedentary farmers utilizing the rivers for irrigation and supplementing their diet with some hunting and gathering. The active farming led the Pima to develop larger communities than their neighboring tribes, along with complex political organizations. From the time of their early encounter with European and American colonizers, Pima Indians have been seen as a friendly people. As of the early 21st century, there are about 11,000 Pima descendants. J. William Lloyd, an amateur ethnographer who lived with the Pima people for two months in 1903, collected and transcribed Comalk-hawk-kih (Thin Buckskin)’s tradi- tional Pima stories via the interpretation of Edward Hubert Wood, but these stories can be traced back to the time of or even before the arrival of the Europeans. The stories are organized as Stories of the First Night, the Second Night, the Third Night, and the Fourth Night.

Written by Kyounghye Kwon

Selections from Aw-aw-tam Indian nights: Being the Myths and Legends of the Pimas of Arizona

J. William Lloyd

License: Public Domain

The Story of These Stories

WHEN I was at the Pan-American Fair, at Buffalo, in July, 1901, I one day strolled into the Bazaar and drifted naturally to the section where Indian curios were displayed for sale by J. W. Benham. Behind the counter, as salesman, stood a young Indi- an, whose frank, intelligent, good-natured face at once attracted me. Finding me interested in Indian art, he courteously invited me behind the counter and spent an hour or more in explain- ing the mysteries of baskets and blankets.

How small seeds are! From that interview came everything that is in this book.

Several times I repeated my visits to my Indian friend, and when I had left Buffalo I had earned that his name was Edward Hubert Wood, and that he was a full-blooded Pima, educated at Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Afterward we came into a pleasant correspondence, and so I came to know that one of my Indian friend’s dreams was that he should be the means of the preservation of the ancient tales of his people. He had a grand-uncle, Comalk-Hawk-Kih, or Thin Buckskin, who was a see-nee-yaw-kum, or professional traditionalist, who knew all the ancient stories, but who had no successor, and with whose death the stories would disappear. He did not feel himself equal to putting these traditions into good English, and so did not quite know what to do.

We discussed this matter in letters; and finally it was de- cided that I should visit the Gila River Reservation, in Arizona, where the Pimas were, and get the myths from the old seeneeyawkum in person, and that Mr. Wood should return home from Pyramid Lake, Nevada, where he was teaching carpentry to the Pai-utes, and be my host and interpreter.

So, on the morning of July 31st, 1903, I stepped from a train at Casa Grande, Arizona, and found myself in the desert land of which I had so long dreamed. I had expected Mr. Wood to meet me there, but he was not at the station and therefore I took passage with the Irish mail-carrier whose stage was in daily transit between Casa Grande and Sacaton, the Agency village of the Pima Reservation.

We had driven perhaps half the distance, and my Irish friend was beguiling the tedium by an interminable series of highly spiced yarns, calculated to flabbergast the tenderfoot, when my anxious eyes discerned in the dis- tance the oncoming of a neat little open buggy, drawn by two pretty ponies, one of which was a pinto, and in which sat Mr. Wood. Just imagine: It was the last day of July, a blazing morning in the open desert, with the temperature soaring somewhere between 100 and 120 degrees, yet here was my Indian friend, doubtless to do me honor, arrayed in a “pepper-and-salt” suit, complete with underclothes; vest buttoned up; collar and necktie, goggles and buckskin driving gloves. And this in an open buggy, while the Irishman and I, under our tilt, were stripped to our shirts, with sleeves rolled above elbows, and swigging water, ever and anon, from an enormous canteen swathed in wet flannel to keep it cool. Truly Mr. Wood had not intended that I should take him for an uncivilized Indian, if clothes could give the lie; but the face was the same kindly one of my “Brother Ed,” and it did not take me long to greet him and transfer myself to his care.

We came to Sacaton (which Ed said was a Mexican name meaning “much tall grass”—reminding me that Em- ory, of the “Army of the West,” who found the Pimas in 1846, reported finding fine meadows there—but which the Pimas call Tawt-sit-ka, “the Place of Fear and Flight,” because of some Apache-caused panic) but we did not stop there, but passed around it, to the Northwest, and on and over the Gila, Akee-mull, The River, as the Pimas affectionately call it, for to them it is as the Nile to Egypt. The famous Gila is not a very imposing stream at any time, and now was no stream at all, but a shallow dry channel, choked with desert dust, or paved with curling flakes of baked mud which cracked like bits of broken pottery under our ponies’ feet. But I afterwards many times saw it a turbid torrent of yellow mud, rushing and foaming from the mountain rains; perilous with quicksand and snag, the roaring of its voice heard over the chapparal for miles to windward.

The Pimas live in villages, each with its sub-chief, and we were bound for the village of Lower San-tan. But in these villages the houses are now seldom aggregated, as in old days of Apache and Yuma war, but scatter out for miles in farm homesteads.

Brother Ed had lately sold his neat farmstead, near Sacaton, and when I came to his home I found he was temporarily living under a vachtoe (pronounce first syllable as if German), or arbor-shed, made of mezquite forks, supporting a flat roof of weeds and brush for shade. Near by he was laying the foundations of a neat little adobe cottage, which was finally completed during my stay.

Ed introduced me to his mother, a matronly Indian woman of perhaps fifty-five, who must have been quite a belle in her day, and whose features were still regular and strong, and his step-father, “Mr. Wells,” who deserves more than a passing word from me, for his kindness was unremitting (bless his good-natured, smiling face!) and his solicitude for my comfort constant. These were all the family, for Ed himself was a widower. Fifty yards or so to the northwest were the huts of two old and wretchedly poor Pimas (the man was blind) who had been allowed to settle there temporarily by Mr. Wood, owing to some difficulty about their own location on their adjoining land. One or two hundred yards in the other direction were two old caw-seens, or storehouses, square structures of a sort of wattlework of poles, weeds and brush, plastered over with adobe and roofed with earth. In one of these I placed my trunk, and on its flat roof I slept, rolled in my blankets, most of the nights of the two months of my stay. I came to know it as “my Arizona Bedstead,” and I shall never forget it and its quaint, crooked ladder.

My Indian brother was not slow in shedding his dress-parade garments, and in getting down to the comfort of outing shirt and overalls, neck handkerchief and sombrero. Then I had my first meal with Indians in Arizona. Mrs. Wells, or as I prefer to call her, Sparkling-Soft-Feather (her Indian name) was a good cook of her kind, and gave us a meal of tortillas, frijole beans, peppers (kaw-awl-kull), coffee, and choo-oo-kook or jerked beef. Ed and I were given the dignity of chairs and a table, but the elder Indians squatted on the ground in the good old Pima way, with their dishes on a mat. There were knives and spoons, but no forks, and the usefulness of fingers was not obsolete. A waggish, pale-eyed pup, flabbily deprecative and good-natured, and a big-footed Mexican choo-chool, or chick- en, were obtrusively familiar. Neither of the older Indians could speak a word of English, but chatted and laughed away together in Pima. The hot, soft wind of the desert kissed our faces as we ate, and off in the back ground rose the stately volcanic pile of Cheoff-skaw-mack, the nearest mountain, and all around the horizon other bare volcanic peaks burned into the blue. Sometimes a whirlwind of dust travelled rapidly over the plain, making one ponder what would happen should it gyrate into the vachtoe.

The old woman from the near-by kee slunk by as we ate, going to the well. She wore gah-kai-gey-aht-kum-soosk (literally string-shoes), or sandals, of rawhide, on her feet, and was quite the most wretched-looking hag I ever saw among the Pimas. Her withered body was hung with indescribable rags and her gray hair was a tangled mat. Yet I came to know that that wretched creature had a heart and a good one. She was kind and cheerful, industrious and uncomplaining, and devotion itself to her old blind husband; who did nothing all day long but move out of the travelling sun into the shade, rolling nearly naked in the dust.

After dinner we got our guns and started out to go to the farm of old Thin Buckskin (“William Higgins,” if you please!) the seeneeyawkum I had come so far to see. Incidentally we were to shoot some kah-kai-cheu, or plumed quails, and taw-up-pee, or rabbits, for supper.

We found the old man plowing for corn in his field. The strong, friendly grasp he gave my hand was all that could be desired. Tall, lean, dignified, with a harsh. yet musical voice; keen, intelligent black eyes, and an impressive manner, he was plainly a gentleman and a scholar, even if he could neither read nor write, nor speak a sentence of English.

The next afternoon he came, and under Ed’s vachtoe gave me the first installment of the coveted tales. It was slow work. First he would tell Ed a paragraph of tradition, and Ed would translate it to me. Then I would write it down, and then read it aloud to Ed again, getting his corrections. When all was straight, to his satisfaction, we would go on to another paragraph, and so on, till the old man said enough. As these Indians are all Christianized now, and mostly zealous in the faith, I could get no traditions on Sunday. And indeed, when part way thru, this zeal came near balking me altogether. A movement started to stop the recovery of these old heathen tales; the sub-chief had a word with Comalk, who became suddenly too busy to go on with his narrations, and it took increased shekels and the interposition of the Agent, Mr. J. B. Alexander, who was very kind to me, before I could get the wheels started again.

Sometimes the old man came at night, instead of afternoon, and I find this entry in my journal: “Sept. 6.—We sat up till midnight in the old cawseen getting the traditions. It was a wild, strange scene-the old cawseen interior, the mesquite forks that supported the roof, the poles overhead, and weeds above that, the mud-plastered walls with loop-hole windows; bags, boxes, trunks, ollas, and vahs-hrom granary baskets about. Ed sitting on the ground, against the wall, nodding when I wrote and waking up to interpret; the old man bent forward, both hands out, palms upward, or waving in strange eloquent gestures; his lean, wrinkled features drawn and black eyes gleaming; telling the strange tales in a strange tongue. On an old olla another Indian, Miguel, who came in to listen, and in his hand a gorgeously decorated quee-a-kote, or flute, with which, while I wrote, he would sometimes give us a few wild, plaintive, thrilling bars, weird as an incantation. And finally myself, sitting on a mattress on my trunk, writing, fast as pencil could travel, by the dim light of a lantern hung against a great post at my right. Outside a cold, strong wind, for the first time since I came to Arizona, bright moonlight, and some drifting white clouds telling the last of the storm.”

Again, on Sept. 12th: “Traditions, afternoon and until midnight. I shall never forget how the half-moon looked, rising over Vah-kee-woldt-kee, or the Notched Cliffs, toward midnight, while the coyotes laughed a chorus some- where off toward the Gila, and we sat around, outdoors, in the wind, and heard the old seeneeyawkum tell his weird, incoherent tales of the long ago.”

My interpreter was eager and willing, and well-posted in the meaning of English, and was a man of unusual intelligence and poetry of feeling, but was not well up in grammar, and in the main I had to edit and recast his sentences; yet just as far as possible I have kept his words and the Indian idiom and simplicity of style. Sometimes he would give me a sentence so forceful and poetic, and otherwise faultless, that I have joyfully written it down exactly as received. I admit that in a very few places, where the Indian simplicity and innocence of thought caused an almost Biblical plainness of speech on family matters, I have expurgated and smoothed a little for prudish Cau- casian ears, but these changes are few, and mostly unimportant, leaving the meaning unimpaired. And never once was there anything in the spirit of what was told me that revealed foulness of thought. All was grave and serious, as befitted the scriptures of an ancient people.

Occasionally I have added a word or sentence to make the meaning stand out clearer, but otherwise I have taken no liberties with the original.

As a rule the seeneeyawkum told these tales in his own words, but the parts called speeches were learned by heart and repeated literally. These parts gave us much trouble. They were highly poetic, and manifestly mystic, and therefore very difficult to translate with truthfulness to the involved meanings and startling and obscure metaphors. Besides they contained many archaic words, the meaning of which neither seeneeyawkum nor interpreter now knew, and which they could only translate by guess, or leave out altogether. But we did the best we could.

The stories were also embellished with songs, some of which I had translated. They were chants of from one to four lines each, seldom more than two, many times repeated in varying cadence; weird, somber, thrillingly passion- ate in places, and by no means unmusical, but, of course, monotonous. I obtained phonograph records of a number, and the translations given are as literal as possible.

As to the meaning of the tales I got small satisfaction. The Indians seemed to have no explanations to offer. They seemed to regard them as fairy tales, but admitted they had once been believed as scriptures.

My own theory came to be that they had been invented, from time to time, by various and successive mah- kais to answer the questions concerning history, phenomena, and the origin of things, which they, as the reputed wisest of the tribe, were continually asked. My chief reason for supposing this is because in almost every tale the hero is a mahkai of some sort. The word mah-kai (now translated doctor, or medicine-man) seems to have been applied in old time to every being capable of exerting magical or supernatural and mysterious power, from the Creator down; and it is easy to see how such use of the word would apparently establish the divine relationship and bolster the authority of the medicine men, while the charm of the tale would focus attention upon them. The temp- tation was great and, I think, yielded to.

I doubt if much real history is worked in, or that it is at all reliable.

All over the desert, where irrigation was at all practicable, in the Gila and Salt River valleys, and up to the edge of the mountains, among the beautiful giant cactus and flatbean trees, you will ride your bronco over evidences of a prehistoric race:—old irrigating ditches, lines of stone wall; or low mounds of adobe rising above the grease, wood and cacti, and littered over profusely with bits of broken and painted pottery, broken cornmills and grinders, per- haps showing here and there a stone ax, arrowhead, or other old stone implement. These mounds (vah-ahk-kee is the Pima word for such a ruin) are the heaps caused by the fallen walls of what were once pueblos of stone and clay. In some places there must have been populous cities, and at the famous site of Casa Grande one finds one of the buildings still standing—a really imposing citadel, with walls four or five feet thick, several stories high, and habit- able since the historic period.

Now according to these traditions it was the tribes now known as Pimas, Papagoes, Yumas and Maricopas, that invaded the land, from some mythic underworld, and overthrew the vahahkkees & killed all their inhabitants, and this is the most interesting part of the tales from a historic point of view. Fewkes, and other ethnologists, think the ancestors of the Pimas built the Casa Grande & other vahahkkees, but I doubt this. Is it reasonable to suppose that if a people as intelligent & settled as the Pimas had once evoluted far enough in architecture & fortification to erect such noble citadels and extensive cities as those of Casa Grande & Casa Blanca, that they, while still surrounded by the harassing Apaches, would have descended to contentment with such miserable & indefensible hovels as their present kees and cawseens? To me it is not. They are as industrious as any of the pueblo-building Indians, not otherwise degenerate, and had they once ever builded pueblos I do not think would have abandoned the art. But it is easy to understand that a horde of desert campers, overthrowing a more civilized nation, might never rebuild or copy after its edifices. So far, then, I am inclined to agree with the traditions and disagree with the ethnologists.

But these traditions are evidently very ancient. They appear to me to have originated from the aborigines of this country; people who knew no other. land. Every story is saturated with local color. From the top of Cheoffskaw- mack, I believe I could have seen almost every place mentioned in the traditions, except the Rio Colorado & the ocean, and the ocean was to them, I believe, little more than a name. They never speak of it with their usual sketchy & graphic detail, and the fact that in the ceremony of purification it is spoken of as a source of drinking water shows they really knew nothing of it. The Indian is too exact in his natural science to speak of salt water as potable. And these stories certainly say that the dwellers in the vahahkkees were the children of Ee-ee-toy, created right here. And that the army that carried out Ee-ee-toy’s revenge upon his rebellious people were the children of Juhwerta Mahkai, who had been somewhere else since the flood, but who were also originally created here.

Now, for what it is worth, I will give a theory to reconcile these differences. I assume that their flood was a real event, but a local one, and the greater part of the people destroyed by it. A minority escaped by flight into the desert, and neither they nor their descendants, for many generations, returned to the place where the catastrophe occurred. Another remnant escaped by floating on various objects & climbing mountains. The first were those of whom it is fabled that Juhwerta Mahkai let them escape thru a hole in the earth. These became nomadic, desert dwellers. The second remained in the Gila country, became agricultural & settled in habit, irrigating their land & building pueblos, growing rich, effeminate & inapt at war. At length the desert fugitives, also grown numerous, and warlike & fierce with the wild, wolf-like existence they had led, and moved by we know not what motives of revenge or greed, returned & swept over the land, in a sudden invasion, like a swarm of locusts; ruthlessly destroying the vahahkees and all who dwelt therein; breaking even the ma-ta-tes & every utensil in their vandal fury; dividing the region thus taken among themselves. According to these traditions the Apaches were already dwellers in the outly- ing deserts & mountains, and were not affected especially by this invasion.

Is it now unreasonable to suppose that some of the invaders kept up, to a great extent, their old habits of desert wandering (Papagoes for instance), and that others adopted to some extent the agricultural habits of those they had conquered, and yet retained, with slight change, the little brush & mud houses & arbors they had grown accus- tomed to in their wanderings? These last would be our present Pimas.

If it is considered strange that these adopted the habits, to any extent, of those they supplanted it may be urged that they almost certainly, in conquering the vahahkkee people, spared and married many of the women, and adopted many of the children; this being in accordance with their custom in historic times. And this infusion of the gentler blood may have been very large. And these women would naturally go on, and would be required by their new husbands to go on, with the agricultural methods to which they were accustomed & would teach them to their new masters. And their children, being wholly or partly of the old stock, would have a natural tendency to the same work, to some extent.

This theory not only explains & agrees with the main parts of the old traditions, but seems confirmed by other things. Thus the Pimas, Papagoes, Quojatas, and the “Rabbit-Eaters” of Mexico, speak about the same language, which would seem to prove them originally the same people. But some have kept the old ways, some have become agricul- tural, and some are in manners between, and thus have become classed as different tribes. And, judging from the remains, the life of the old vahahkkee dwellers was in many ways like that of the modern Pima, only less primitive.

But the real value of these stories is as folklore, and in their literary merit. They throw a wonderful side-light on the old customs, beliefs and feelings. I consider them ancient, in the main, but do not doubt that in coming down thru many seeneeyawkums they have been much modified by the addition of embellishment, the subtraction of forgetfulness. As proof I adduce the accounting for the origin of the white people, who use pens & ink, in the story of Van-daih. The ancient Pimas knew neither white men, nor pens, nor ink, therefore this passage is clearly an interpolation by some later narrator, if the story is really ancient, as I suppose it is. In the story of Noo-ee’s meeting the sun, the word used by old Comalk, for the sun’s weapon, was vai-no-ma-gaht (literally iron-bow) which is the modern Pima’s name for the white man’s gun, and it was translated as gun by my interpreter. But iron and guns were both unknown to ancient Pimas, therefore this term must have been first used by some seeneeyawkum after the white man came, who thought a gun more appropriate than a bow for the sun’s shooting.

How much has been lost by forgetfulness we can never know; but at least I found that the meaning of many ancient words had disappeared, that the mystic meaning of the highly symbolic speeches seemed all gone, and I felt certain that the last part of the Story of the Gambler’s War had been lost by forgetting; for it stops short with the pre- liminary speeches, instead of going on with a detailed account of the battles as does the Story of Paht-ahn-kum’s war.

Another proof that these tales were changed by different narrators is afforded by the variants of some of them published by Emory, Grossman, Cook, and other writers about the Pimas.

As to the mystic meaning I can only guess. The mystic number four, so constantly used, probably refers to the four cardinal points, but my Indians seemed not aware of this. In the stories, West is black, East is white or light, South is blue, North is yellow, and Above is green. Of course the west is black because there night swallows up the sun, and the east is light because it gives the sun, but why south is blue and north is yellow I do not know. But south is the nearest way to the ocean, and as in one story the word ocean seems used in place of south, I infer the blue color was derived from that. And the desert lying north of the ocean may suggest the desert tint, yellow, as the color of the north. As to the sky being green, I find this in my journal: “August 29-Last evening, after sunset, there were the most wonderful sky effects-there was a line of light clouds across the sky, in the west, about half way up to the zenith, and suddenly the white part of these was washed over, as tho by a paint brush, with a strong but delicate pea-green, while under this spread a mist or haze of dainty pink, changing to a rich, delicate mauve. Lasted quar- ter of an hour or more. Never saw anything like it in nature before.” Again, on September 6, I saw nearly the same phenomenon. The green was very strong and vivid, and could not fail to attract an Indian’s eye, and something of the sort, I fancy, made him make the strange choice of green for the sky color.

Those who like to compare myths and folktales and ancient scriptures will find a rich field here. And the in- teresting thing is that these tales come straight from a line of Indians who could neither read nor write nor speak English, therefore adulteration by white man’s literature seems improbable.

As to the literary merit of these tales, after all that is lost by a double interpretation, I consider it still very high. You must come to them as a little child, for they are intensely child-like, and to expect them to be like a white man’s narrative is absurd. But they are sketched in such clear, bold lines, with such a sure touch and delicate expressive- ness of salient points; there are such close-fitting, shrewd bits of human nature; such real yet startling touches of poetry in metaphor; such fertile and altogether Indian imagination in plot and incident, that the interest never fails. No two stories are alike, and if surprise is a literary charm of high value, and I think it is, then these tales are certainly charming, for they constantly bring surprise.

And the, poetry, in Eeeetoy’s speech for example, is so rich and strong; and in such parts as the story of the Nah-vah-choo the mysticism seems to challenge one like a riddle.

When these old tales were told with all proper ceremony and respect, they were told on four successive nights. This could not be in the giving of them to me, for many practical reasons, but I have endeavored to give them that form for my reader and hence the title of my book. But I did not discover how many or what ones were told on any one night, so my division is arbitrary, and only aims at reasonable equality. The naming, too, of the different stories is try own, for the old man did not appear to have any set names for them. I fancy the old man was rusty and out of practice, and forgot some of the tales in their proper sequence, and brought them in afterward as they recurred to him.. For instance, the story of Tcheu-nas-set Seeven’s singing away another chief ’s wives evidently belongs among the early stories of the vahahkkee people, and before the account of his death, when the vahahkkees were destroyed. But I have given the stories in the order in which they were told to me, leaving all responsibility on the old see- neeyawkum’s shoulders.

I lived a little more than two months with these Indians, collecting these stories, enjoying their kindly hospitality, living as they lived, eating their food, riding their ponies, sleeping on their roofs under the splendid Arizona stars.

I shall never forget that day, before I left, when Ed and I saddled our ponies in the early morning and rode twenty milts to the Casa Grande ruins. On the way we crossed the dry bed of the Gila; and passed thru the Agen- cy village of Sacaton and the village of Blackwater; skirting the Maricopa Slaughter mountains, where once some unfortunate Maricopias were waylaid and massacred by a band of Apaches, almost in sight of Sacaton. The Casa Grande ruins are imposing enough, but sadly belittled in effect by the well-meant roof which the government has erected over them to preserve them. This kills all the poetry and gives them the ludicrous aspect of a museum spec- imen. Had the old walls been skillfully capped with a waterproof cement and the walls coated with some weath- erproof and transparent wash, all necessary security could have been effected with perhaps less expense than this absurd roof, and all the romance of impression preserved. Let us hope the genial and manly young custodian, Mr. Frank Pinckly, to whose warm-hearted hospitality and that of his parents I owe grateful thanks, will consider this suggestion favorably and earn the blessing of future travellers. A storm broke on us while we were at the ruins, and riding home that evening we found the Gila flooded. I shall always remember how its muddy torrent looked to me, plunging along at my feet, where that morning I had crossed dry shod; its yellow waves shot with blood-red reflec- tions from the last colors of sunset.

“You better see that Pinto’s cinch is tight, or she may try to get you off in the river,” warned Ed, in my ear, as he jumped off to cinch. up “Georgie.”

It was always exciting to me to ford the treacherous Gila, the tawny waters were so sweeping, and the ponies plunged so when their feet felt the quicksands, but we got across all right, and galloped home on the slippery, mud- dy roads.

When I left these people it was with a genuine regard for their virtues. I found them in the main kind, honest, simple-minded, industrious, surprisingly clean, considering their obstacles of scant water and ever-present dust., and the calmest tempered people I have ever known.

I remember the second day of my stay we were going to ride to the Casa Blanca ruins. In watering the ponies at the well, “Georgie’s” loosened saddle turned and swung under his belly. Such bucking and frantic kicking as that half-broken colt indulged in for a few moments would have made a congress of cow-boys applaud, and when it was over the beautiful colt stood exhausted on the far side of a twenty acre field, with the saddle fragments somewhere between. Now to poor Indians the loss of a saddle is not small, and I fancy most frontiersmen, under the provo- cation, would have made the air blue with oaths, but Ed only sadly said: “I’m afraid that spoils Georgie,” and the stepfather laughed and started patiently out on the trail of the colt “to save the pieces,” while the mother took one of her bowl-shaped Pima baskets, with beans in it, and coaxed the colt till she caught him. Then he was patted and soothed and fed with sugar, the saddle patched up and replaced, and we rode eighteen miles that day and never another mishap. And from first to last never a harsh or complaining word.

I at no time encountered a beggar among the Pimas, and tho they were mostly very poor I had not a pin’s worth stolen. I never heard an oath, or saw a brutal or violent act, or a child slapped or scolded, or a woman treated with disrespect or tyranny, nor any drunkenness or cruelty to animals. Perhaps I was especially fortunate, but I can only speak of what I saw. Their self-respect and serenity continually aroused my admiration.

I must say that they appeared to me to excel any average white neighborhood in good behavior.

It is a strange land, that in which the Pimas dwell; a desert overgrown with strange soft-tinted weeds, “salt weeds,” pink, red, green, gray, blue, purple; the rich-green yellow-flowering greasewood; odd cacti, and all manner of thornbearing bushes. The soil is inexhaustibly rich, were there water enough, but the white people, settling above the Indians, on the Gila, have so withdrawn the water that crop failures from lack of sufficient irrigation are the rule, now, instead of the exception, and the once ever-flowing Gila is more often a dry channel, as sun-baked as the desert around it.

All around their valley, and rising here and there from the plain, are low volcanic peaks, mere dead masses of rock except where in places a giant cactus stands candelabra-like among the slopes of stone. About the feet of these mountains, and along the channels where the torrents rush down in times of rain, are weird forests of desert growths, mesquite, cat-claw, flat-beans, screw-beans, greasewood, giant-cactus, cane-cactus, white-cactus, chol- la-cactus, and a host of others, almost everything bristling with innumerable thorns.

On this strange pasture of weed and thorn the Indian’s ponies & his few cattle graze.

Here in summer the sun beats down till the mercury registers 118 to 120 degrees in the shade, and dust storms & dust whirlwinds travel over the burning plain.

Stories of the First night

The Traditions of the Pimas

The old man, Comalk Hawk-Kih, (Thin Buckskin) began by saying that these were stories which he used to hear his father tell, they being handed down from father to son, and that when he was little he did not pay much attention, but when he grew older he determined to learn them, and asked his father to teach him, which his father did, and now he knew them all.

The Story of Creation

In the beginning there was no earth, no water—nothing. There was only a Person, Juh-wert-a-Mah-kai (The Doctor of the Earth).

He just floated, for there was no place for him to stand upon. There was no sun, no light, and he just floated about in the darkness, which was Darkness itself.

He wandered around in the nowhere till he thought he had wandered enough. Then he rubbed on his breast and rubbed out moah-haht-tack, that is perspiration, or greasy earth. This he rubbed out on the palm of his hand and held out. It tipped over three times, but the fourth, time it staid straight in the middle of the air and there it remains now as the world.

The first bush he created was the greasewood bush.

And he made ants, little tiny ants, to live on that bush, on its gum which comes out of its stem.

But these little ants did not do any good, so be created white ants, and these worked and enlarged the earth; and they kept on increasing it, larger and larger, until at last it was big enough for himself to rest on.

Then he created a Person. He made him out of his eye, out of the shadow of his eyes, to assist him, to be like him, and to help him in creating trees and human beings and everything that was to be on the earth.

The name of this being was Noo-ee (the Buzzard).

Nooee was given all power, but he did not do the work he was created for. He did not care to help Juhwerta- mahkai, but let him go by himself.

And so the Doctor of the Earth himself created the mountains and everything that has seed and is good to eat. For if he had created human beings first they would have had nothing to live on.

But after making Nooee and before making the mountains and seed for food, Juhwertamahkai made the sun. In order to make the sun he first made water, and this he placed in a hollow vessel, like an earthen dish (hwas-hah-ah) to harden into something like ice. And this hardened ball he placed in the sky. First he placed it in the North, but it did not work; then he placed it in the West, but it did not work; then he placed it in the South, but it did not work; then he placed it in the East and there it worked as he wanted it to.

And the moon he made in the same way and tried in the same places, with the same results.

But when he made the stars he took the water in his mouth and spurted it up into the sky. But the first night his stars did not give light enough. So he took the Doctor-stone (diamond), the tone-dum-haw-teh, and smashed it up, and took the pieces and threw them into the sky to mix with the water in the stars, and then there was light enough.

And now Juhwertamahkai, rubbed again on his breast, and from the substance he obtained there made two little dolls, and these he laid on the earth. And they were human beings, man and woman.

And now for a time the people increased till they filled the earth. For the first parents were perfect, and there was no sickness and no death. But when the earth was full, then there was nothing to eat, so they killed and ate each other.

But Juhwertamahkai did not like the way his people acted, to kill and eat each other, and so he let the sky fail to kill them. But when the sky dropped he, himself, took a staff and broke a hole thru, thru which he and Nooee emerged and escaped, leaving behind them all the people dead.

And Juhwertamahkai, being now on the top of this fallen sky, again made a man and a woman, in the same way as before. But this man and woman became grey when old, and their children became grey still younger, and their children became grey younger still, and so on till the babies were gray in their cradles.

And Juhwertamahkai, who had made a new earth and sky, just as there had been before, did not like his people becoming grey in their cradles, so he let the sky fall on them again, and again made a hole and escaped, with Nooee, as before.

And Juhwertamahkai, on top of this second sky, again made a new heaven and a new earth, just as he had done before, and new people.

But these new people made a vice of smoking. Before human beings had never smoked till they were old, but now they smoked younger, and each generation still younger, till the infants wanted to smoke in their cradles.

And Juhwertamahkai did not like this, and let the sky fall again, and created everything new again in the same way, and this time he created the earth as it is now.

But at first the whole slope of the world was westward, and tho there were peaks rising from this slope there were no true valleys, and all the water that fell ran away and there was no water for the people to drink. So Juhwer- tamahkai sent Nooee to fly around among the mountains, and over the earth, to cut valleys with his wings, so that the water could be caught and distributed and there might be enough for the people to drink.

Now the sun was male and the moon was female and they met once a month. And the moon became a mother and went to a mountain called Tahs-my-et-tahn Toe-ahk (sun striking mountain) and there was born her baby. But she had duties to attend to, to turn around and give light, so she made a place for the child by tramping down the weedy bushes and there left it. And the child, having no milk, was nourished on the earth.

And this child was the coyote, and as he grew he went out to walk and in his walk came to the house of Juhwer- tamahkai and Nooee, where they lived.

And when he came there Juhwertamahkai knew him and called him Toe-hahvs, because he was laid on the weedy bushes of that name.

But now out of the North came another powerful personage, who has two names, See-ur-huh and Ee-ee-toy.

Now Seeurhuh means older brother, and when this personage came to Juhwertamahkai, Nooee and Toehahvs he called them his younger brothers. But they claimed to have been here first, and to be older than he, and there was a dispute between them. But finally, because he insisted so strongly, and just to please him, they let him be called older brother.

Juhwerta Mahkai’s Song Of Creation

Juhwerta mahkai made the world—

Come and see it and make it useful!

He made it round—

Come and see it and make it useful!

Notes on “The Story of Creation”

The idea of creating the earth from the perspiration and waste cuticle of the Creator is, I believe, original. The local touch in making the greasewood bush the first vegetation is very strong.

In the tipping over of the earth three times, and its standing right the fourth time, we are introduced to the first of the mystic fours in which the whole scheme of the stories is cast. Almost everything is done four times before finished.

The peculiar Indian idea of type-animals, the immortal and supernatural representatives of their respective an- imal tribes, appears in Nooee and Toehahvs, and here again the local color is rich and strong in making the buzzard and the coyote, the most common and striking animals of the desert, the particular aides on the staff of the Creator.

Might not the creation of Nooee out of the shadow of the eyes of the Doctor of the Earth be a poetical allusion to the flying shadow of the buzzard on the sun-bright desert?

In the creation of sun and moon we find the mystic four referred to the four corners of the universe, North, South, East and West, and this, I am persuaded, is really the origin of its sacred significance, for most religions find root and source in astronomy.

In the dropping of the sky appears the old idea of its solid character.

In the “slope of the world to the Westward” there is something curiously significant when we remember that both the Gila and Salt Rivers flow generally westward.

Nooee cuts the valleys with his wings. It would almost appear that Nooee was Juhwertamahkai’s agent in the air and sky, Toehahvs on earth.

The night-prowling coyote is appropriately and poetically mothered by the moon.

And here appears Eeeetoy, the most active and mysterious personality in Piman mythology. Out of the North, apparently self-existent, but little inferior in power to Juhwertamahkai, and claiming greater age, he appears, by pure “bluff ” and persistent push and wheedling, to have induced the really more powerful, but good-natured and rather lazy Juhwertamahkai to give over most of the real work and government of the world to him. In convers- ing with Harry Azul, the head chief ’s son, at Sacaton, I found he regarded Eeeetoy and Juhwertamahki as but two names for the same. And indeed it is hard to fix Eeeetoy’s place or power.

The Story of the Flood

Now Seeurhuh was very powerful, like Juhwerta Mahkai, and as he took up his residence with them, as one of them, he did many wonderful things which pleased Juhwerta Mahkai, who liked to watch him.

And after doing many marvelous things he, too, made a man.

And to this man whom he had made, Seeurhuh (whose other name was Ee-ee-toy) gave a bow & arrows, and guarded his arm against the bow string by a piece of wild-cat skin, and pierced his ears & made ear-rings for him, like turquoises to look at, from the leaves of the weed called quah-wool. And this man was the most beautiful man yet made.

And Ee-ee-toy told this young man, who was just of marriageable age, to look around and see if he could find any young girl in the villages that would suit him and, if he found her, to see her relatives and see if they were will- ing he should marry her.

And the beautiful young man did this, and found a girl that pleased him, and told her family of his wish, and they accepted him, and he married her.

And the names of both these are now forgotten and unknown.

And when they were married Ee-ee-toy, foreseeing what would happen, went & gathered the gum of the grease- wood tree.

Here the narrative states, with far too much plainness of circumstantial detail for popular reading, that this young man married a great many wives in rapid succession, abandoning the last one with each new one wedded, and had children with abnormal, even uncanny swiftness, for which the wives were blamed and for which suspicion they were thus heartlessly divorced. Because of this, Juhwerta Mahkai and Ee-ee-toy foresaw that nature would be convulsed and a great flood would come to cover the world. And then the narrative goes on to say:

Now there was a doctor who lived down toward the sunset whose name was Vahk-lohv Mahkai, or South Doctor, who had a beautiful daughter. And when his daughter heard of this young man and what had happened to his wives she was afraid and cried every day. And when her fattier saw her crying he asked her what was the matter? was she sick? And when she had told him what she was afraid of, for every one knew and was talking of this thing, he said yes, he knew it was true, but she ought not to be afraid, for there was happiness for a woman in marriage and the mothering of children.

And it took many years for the young man to marry all these wives, and have all these children, and all this time Ee-ee-toy was busy making a great vessel of the gum he had gathered from the grease bushes, a sort of olla which could be closed up, which would keep back water. And while he was making this he talked over the reasons for it with Juhwerta Mahkai, Nooee, and Toehahvs, that it was because there was a great flood coming.

And several birds heard them talking thus—the woodpecker, Hick-o-vick; the humming-bird, Vee-pis-mahl; a little bird named Gee-ee-sop, and another called Quota-veech.

Eeeetoy said he would escape the flood by getting into the vessel he was making from the gum of the grease bushes or ser-quoy.

And Juhwerta Mahkai said he would get into his staff, or walking stick, and float about. And Toehahvs said he would get into a cane-tube.

And the little birds said the water would not reach the sky, so they would fly up there and hang on by their bills till it was over.

And Nooee, the buzzard, the powerful, said he did not care if the flood did reach the sky, for he could find a way to break thru.

Now Ee-ee-toy was envious, and anxious to get ahead of Juhwerta Mahkai and get more fame for his wonderful deeds, but Juhwerta Mahkai, though really the strongest, was generous and from kindness and for relationship sake let Ee-ee-toy have the best of it.

And the young girl, the doctor’s daughter, kept on crying, fearing the young man, feeling him ever coming nearer, and her father kept on reassuring her, telling her it would be all right, but at last, out of pity for her fears & tears, he told her to go and get him the little tuft of the finest thorns on the top of the white cactus, the haht-sahn- kahm, and bring to him.

And her father took the cactus-tuft which she had brought him, and took hair from her head and wound about one end of it, and told her if she would wear this it would protect her. And she consented and wore the cactus-tuft. And he told her to treat the young man right, when he came, & make him broth of corn. And if the young man should eat all the broth, then their plan would fail, but if he left any broth she was to eat that up and then their plan would succeed.

And he told her to be sure and have a bow and arrows above the door of the kee, so that he could take care of the young man.

And after her father had told her this, on that very evening the young man came, and the girl received him kindly, and took his bows & arrows, and put them over the door of the kee, as her father had told her, and made the young man broth of corn and gave it to him to eat.

And he ate only part of it and what was left she ate herself.

And before this her father had told her: “if the young man is wounded by the thorns you wear, in that moment he will become a woman and a mother and you will become a young man.”

And in the night all this came to be, even so, and by day-break the child was crying.

And the old woman ran in and said: “Mossay!” which means an old woman’s grandchild from a daughter.

And the daughter, that had been, said: “It is not your moss, it is your cah-um-maht,” that is an old woman’s grandchild from a son.

And then the old man ran in and said: “Bah-ahm-ah-dah!” that is an old man’s grandchild from a daughter, but his daughter said: “It is not your bah-ahm-maht, but it is your voss-ahm-maht,” which is an old man’s grandchild from a son.

And early in the morning this young man (that had been, but who was now a woman & a mother) made a wawl-kote, a carrier, or cradle, for the baby and took the trail back home.

And Juhwerta Mahkai told his neighbors of what was coming, this young man who had changed into a woman and a mother and was bringing a baby born from himself, and that when he arrived wonderful things would hap- pen & springs would gush forth from under every tree and on every mountain.

And the young man-woman came back and by the time of his return Ee-ee-toy had finished his vessel and had placed therein seeds & everything that is in the world.

And the young man-woman, when he came to his old home, placed his baby in the bushes and left it, going in without it, but Ee-ee-toy turned around and looked at him and knew him, for he did not wear a woman’s dress, and said to him: “Where is my Bahahmmaht? Bring it to me. I want to see it. It is a joy for an old man to see his grandchild.

I have sat here in my house and watched your going, and all that has happened you, and foreseen some one would send you back in shame, although I did not like to think there was anyone more powerful than I. But never mind, he who has beaten us will see what will happen.”

And when the young man-woman went to get his baby, Ee-ee-toy got into his vessel, and built a fire on the hearth he had placed therein, and sealed it up.

And the young man-woman found his baby crying, and the tears from it were all over the ground, around. And when he stooped over to pick up his child he turned into a sand-snipe, and the baby turned into a little teeter-snipe. And then that came true which Juhwerta Mahkai had said, that water would gush out from under every tree & on every mountain; and the people when they saw it, and knew that a flood was coming, ram to Juhwerta Mahkai; and he took his staff and made a hole in the earth and let all those thru who had come to him, but the rest were drowned.

Then Juhwerta Mahkai got into his walking stick & floated, and Toehahvs got into his tube of cane and floated, but Ee-ee-toy’s vessel was heavy & big and remained until the flood was much deeper before it could float.

And the people who were left out fled to the mountains; to the mountains called Gah-kote-kih (Superstition Mts.) for they were living in the plains between Gahkotekih and Cheoffskawmack (Tall Gray Mountain.)

And there was a powerful man among these people, a doctor (mahkai), who set a mark on the mountain side and said the water would not rise above it.

And the people believed him and camped just beyond the mark; but the water came on and they had to go higher. And this happened four times.

And the mahkai did this to help his people, and also used power to raise the mountain, but at last he saw all was to be a failure. And he called the people and asked them all to come close together, and he took his doctor-stone (mahkai-haw-teh) which is called Tonedumhawteh or Stone-of-Light, and held it in the palm of his hand and struck it hard with his other hand, and it thundered so loud that all the people were frightened and they were all turned into stone.

And the little birds, the woodpecker, Hickovick; the humming-bird, Veepismahl; the little bird named Ge-ee- sop, and the other called Quotaveech, all flew up to the sky and hung on by their bills, but Nooee still floated in the air and intended to keep on the wing unless the floods reached the heavens.

But Juhwerta Mahkai, Ee-ee-toy and Toehahvs floated around on the water and drifted to the west and did not know where they were.

And the flood rose higher until it reached the woodpecker’s tail, and you can see the marks to this day.

And Quotaveech was cold and cried so loud that the other birds pulled off their feathers and built him a nest up there so he could keep warm. And when Quotaveech was warm he quit crying.

And then the little birds sang, for they had power to make the water go down by singing, and as they sang the waters gradually receded.

But the others still floated around.

When the land began to appear Juhwerta Mahkai and Toehahvs got out, but Ee-ee-toy had to wait for his house to warm up, for he had built a fire to warm his vessel enough for him to unseal it.

When it was warm enough he unsealed it, but when he looked out he saw the water still running & he got back and sealed himself in again.

And after waiting a while he unsealed his vessel again, and seeing dry land enough he got out.

And Juhwerta Mahkai went south and Toehahvs went west, and Ee-ee-toy went northward. And as they did not know where they were they missed each other, and passed each other unseen, but afterward saw each other’s tracks, and then turned back and shouted, but wandered from the track, and again passed unseen. And this happened four times.

And the fourth time Juhwerta Mahkai and Ee-ee-toy met, but Toehahvs had passed already.

And when they met, Ee-ee-toy said to Juhwerta Mahkai “My younger brother!” but Juhwerta Mahkai greeted him as younger brother & claimed to have come out first. Then Ee-ee-toy said again: “I came out first and you can see the water marks on my body.” But Juhwerta Mahkai replied: “I came out first and also have the water marks on my person to prove it.”

But Ee-ee-toy so insisted that he was the eldest that Juhwerta Mahkai, just to please him, gave him his way and let him be considered the elder.

And then they turned westward and yelled to find Toehahvs, for they remembered to have seen his tracks, and they kept on yelling till he heard them. And when Toehahvs saw them he called them his younger brothers, and they called him younger brother. And this dispute continued till Ee-ee-toy again got the best of it, and although really the younger brother was admitted by the others to be Seeurhuh, or the elder.

And the birds came down from the sky and again there was a dispute about the relationship, but Ee-ee-toy again got the best of them all.

But Quotaveech staid up in the sky because he had a comfortable nest there, and they called him Vee-ick-koss- kum Mahkai, the Feather-Nest Doctor.

And they wanted to find the middle, the navel of the earth, and they sent Veeppismahl, the humming bird, to the west, and Hickovick, the woodpecker, to the east, and all the others stood and waited for them at the starting place. And Veepismahl & Hickovick were to go as far as they could, to the edge of the world, and then return to find the middle of the earth by their meeting. But Hickovick flew a little faster and got there first, and so when they met they found it was not the middle, and they parted & started again, but this time they changed places and Hickovick went westward and Veepismahl went east.

And this time Veepismahl was the faster, and Hickovick was late, and the judges thought their place of meeting was a little east of the center so they all went a little way west. Ee-ee-toy, Juhwerta Mahkai and Toehahvs stood there and sent the birds out once more, and this time Hickovick went eastward again, and Veepismahl went west. And Hickovick flew faster and arrived there first. And they said : “This is not the middle. It is a little way west yet.”

And so they moved a little way, and again the birds were sent forth, and this time Hickovick went west and Veepismahl went east. And when the birds returned they met where the others stood and all cried “This is the Hick, the Navel of the World!”

And they stood there because there was no dry place yet for them to sit down upon; and Ee-eetoy rubbed upon his breast and took from his bosom the smallest ants, the O-auf-taw-ton, and threw them upon the ground, and they worked there and threw up little hills; and this earth was dry. And so they sat down.

But the: water was still running in the valleys, and Ee-ee-toy took a hair from his head & made it into a snake— Vuck-vahmuht. And with this snake he pushed the waters south, but the head of the snake was left lying to the west and his tail to the east.

But there was more water, and Ee-ee-toy took another hair from his head and made another snake, and with this snake pushed the rest of the water north. And the head of this snake was left to the east and his tail to the west. So the head of each snake was left lying with the tail of the other.

And the snake that has his tail to the east, in the morning will shake up his tail to start the morning wind to wake the people and tell them to think of their dreams.

And the snake that has his tail to the west, in the evening will shake up his tail to start the cool wind to tell the people it is time to go in and make the fires & be comfortable.

And they said: “We will make dolls, but we will not let each other see them until they are finished.”

And Ee-ee-toy sat facing the west, and Toehahvs facing the south, and Juhwerta Mahkai facing the east.

And the earth was still damp and they took clay and began to make dolls. And Ee-ee-toy made the best. But Juhwerta Mahkai did not make good ones, because he remembered some of his people had escaped the flood thru a hole in the earth, and he intended to visit them and he did not want to make anything better than they were to take the place of them. And Toehahvs made the poorest of all.

Then Ee-ee-toy asked them if they were ready, and they all said yes, and then they turned about and showed each other the dolls they had made.

And Ee-ee-toy asked Juhwerta Mahkai why he had made such queer dolls. “This one,” he said, “is not right, for you have made him without any sitting-down parts, and how can he get rid of the waste of what he eats?”

But Juhwerta Mahkai said: “He will not need to eat, he can just smell the smell of what is cooked.”

Then Ee-ee-toy asked again: “Why did you make this doll with only one leg—how can he run?” But Juh- werta Mahkai replied: “He will not need to run; he can just hop around.”

Then Ee-ee-toy asked Toehahvs why he had made a doll with webs between his fingers and toes—”How can he point directions?” But Toehahvs said he had made these dolls so for good purpose, for if anybody gave them small seeds they would not slip between their fingers, and they could use the webs for dippers to drink with.

And Ee-ee-toy held up his dolls and said: “These are the best of all, and I want you to make more like them.” And he took Toehahv’s dolls and threw them into the water and they became ducks & beavers. And he took Juhwer- ta Mahkai’s dolls and threw them away and they all broke to pieces and were nothing.

And Juhwerta Mahkai was angry at this and began to sink into the ground; and took his stick and hooked it into the sky and pulled the sky down while he was sinking. But Ee-ee-toy spread his hand over his dolls, and held up the sky, and seeing that Juhwerta Mahkai was sinking into the earth he sprang and tried to hold him & cried, “Man, what are you doing? Are you going to leave me and my people here alone?”

But Juhwerta Mahkai slipped through his hands, leaving in them only the waste & excretion of his skin. And that is how there is sickness & death among us.

And Ee-ee-toy, when Juhwerta Mahkai escaped him, went around swinging his hands & saying: “I never thought all this impurity would come upon my people!” and the swinging of his hands scattered disease over all the earth. And he washed himself in a pool or pond and the impurities remaining in the water are the source of the malarias and all the diseases of dampness.

And Ee-ee-toy and Toehahvs built a house for their dolls a little way off, and Ee-ee-toy sent Toehahvs to listen if they were yet talking. And the Aw-up, (the Apaches) were the first ones that talked. And Ee-ee-toy said: “I never meant to have those Apaches talk first, I would rather have had the Aw-aw-tam, the Good People, speak first. “

But he said: “It is all right. I will give them strength, that they stand the cold & all hardships.” And all the differ- ent people that they had made talked, one after the other, but the Awawtam talked last.

And they all took to playing together, and in their play they kicked each other as the Maricopas do in sport to this day; but the Apaches got angry and said: “We will leave you and go into the mountains and eat what we can get, but we will dream good dreams and be just as happy as you with all your good things to eat.”

And some of the people took up their residence on the Gila, and some went west to the Rio Colorado. And those who builded vahahkkees, or houses out of adobe and stones, lived in the valley of the Gila, between the mountains which are there now.

Juhwerta Mahkai’s Song Before The Flood

My poor people,

Who will see,

Who will see

This water which will moisten the earth!

The Song Of Superstition Mountains

We are destroyed!

By my stone we are destroyed!

We are rightly turned into stone.

Ee-Ee-Toy’s Song When He Made The World Serpents

I know what to do;

I am going to move the water both ways.

Notes on “The Story of the Flood”

In the Story of the Flood we are introduced to Indian marriage. Among the Pimas it was a very simple affair. There was no ceremony whatever. The lover usually selected a relative, who went with him to the parents of the girl and asked the father to permit the lover to marry her. Presents were seldom given unless a very old man desired a young bride. The girl was consulted and her consent was essential, her refusal final. If, however, all parties were satisfied, she went at once with her husband as his wife. If either party became dissatisfied, separation at once constituted divorce and either could leave the other. A widow or divorced woman, if courted by another suitor, was approached directly, with no intervention of relatives. Of course, on these terms there were many separations, yet all accounts agree that there was a good deal of fidelity and many life-long unions and cases of strong affection.

Polygamy was not unknown.

Grossman says that the wife was the slave of the husband, but it is difficult to see how a woman, free at any moment to divorce herself without disgrace or coercion, could be properly regarded as a slave. Certainly the men appear always to have done a large part of the hard work, and as far as I could see the women were remarkably equal and independent and respectfully treated, as such a system would naturally bring about. A man would be a fool to ill-treat a woman, whose love or services were valuable to him, if at any moment of discontent she could leave him, perhaps for a rival. The chances are that he would constantly endeavor to hold her allegiance by special kindness and favors.

But today legal marriage is replacing the old system.

So far as I saw the Pimas were very harmonious and kindly in family life.

The birds, gee-ee-sop and quotaveech, were pointed out to me by the Pimas, and as near as I could tell quotaveech was Bendire’s thrasher, or perhaps the curve-bill thrasher. It has a very sweet but timid song. I did not succeed in identifying gee-ee-sop, but find these entries about him in my journal: “Aug. 5—I saw a little bird which I suppose to be a gee-ee-sop in a mezquite today, smaller and more slender than a vireo, but like one in action, but the tail longer and carried more like a brown thrasher, nearly white below, dark, leaden gray above, top of head and tail black.” Again on Sept. 1: “What a dear little bird the gee-ee-sop is! Two of them in the oas-juh-wert-pot tree were looking at me a few minutes back. Dark slate-blue above and nearly white below, with beady black eyes and black, lively tails, tipped with white, they are very pretty, tame and confiding.”

The faith of the Aw-aw-tam in witchcraft appears first in this story and afterwards is conspicuous in nearly all. Almost all diseases they supposed were caused by bewitching, and it was the chief business of the medicine-men to find out who or what had caused the bewitching. Sometimes people were accused and murders followed. This was the darkest spot in Piman life. Generally, however, some animal or inanimate object was identified. Grossman’s account in the Smithsonian Report for 1871 is interesting. In the stories, however, witchcraft appears usually as the ability of the mahkai to work transformations in himself or others, in true old fairy-tale style.

Superstition Mountain derives its name from this story, It is a very beautiful and impressive mountain, with terraces of cliffs, marking perhaps the successive pausing places of the fugitives, and the huddled rocks on the top represent their petrified forms. Some of the older Indians still fear to go up into this mountain, lest a like fate befall them.

What beautiful poetic touches are the wetting of the woodpecker’s tail, and the singing of the little birds to subdue the angry waters.

The resemblances to Genesis will of course be noted by all in these two first stories. Yet after all they are few and slight in any matter of detail.

In Ee-ee-toy’s serpents, that pushed back the waters, there is a strong reminder of the Norse Midgard Serpent.

The making of the dolls in this story is one of the prettiest and most amusing spots in the traditions.

The waste and perspiration of Juhwerta Mahkai’s skin again comes into play, but this time as a malign force instead of a beneficent one. It would also appear from this that the more intelligent Pimas had a glimmering of the fact that there were other causes than witchcraft for disease.

I have generally used the word Aw-aw-tam (Good People, or People of Peace) as synonymous with Pima, but it is sometimes used to embrace all Indians of the Piman stock and may be so understood in this story.

And perhaps this is as good a place as any to say a few descriptive words about these Pimas of Arizona, and their allies, who have from prehistoric times inhabited what the old Spanish historian, Clavigero, called “Pimeria,” that is, the valleys of the Gila and Salt Rivers.

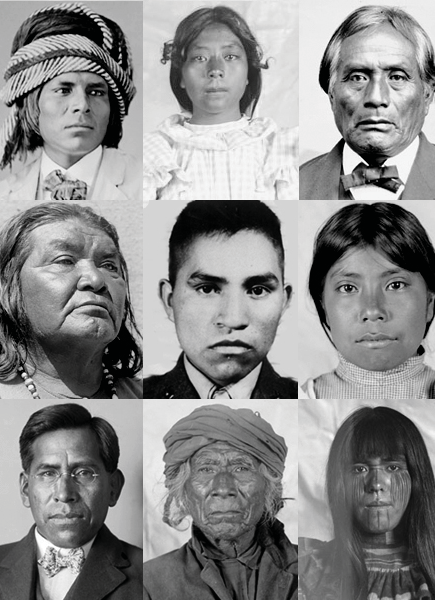

Their faces seemed to me to be of almost Caucasian regularity and rather of an English or Dutch cast, that is rather heavily moulded. The forehead is vertical and inclined to be square; and the chin, broad, heavy and full, comes out well to its line. The nose is straight, or a little irregular, or rounded, at the end, but not often very aq- uiline, never flat or wide-nostriled. The mouth is large but well shaped, with short, white, remarkably even teeth, seldom showing any canine projection. The whole face is a little heavy and square, but the cheek bones are not especially prominent. The eyes are level, frank and direct in glance, with long lashes and strong black brows. In the babies a slight uptilt to the eye is sometimes’ seen, like a Japanese, which indeed the babies suggest. The head of almost all adults is well-balanced and finely poised on a good neck.

Another type possesses more of what we call the Indian feature. The forehead retreats somewhat, so does the chin, while the upper lip is larger, longer, more convex and the nose, above is more aquiline, with wider nostrils. Consequently this face in profile is more convex thru out. The cheek-bones are much more prominent, too, and the head not generally so well-balanced and proportional.

While I have seen no striking beauty I believe the average good looks is greater than among white men, taken as they come.

The women as a rule, however, do not carry themselves gracefully, are apt to be too broad, fat and dumpy in figure, with too large waists, and often loose, ungracefully-moving hips. This deformity of the hips, for it almost amounts to that, I observe among Italian peasant women, too, and some negresses, and, I take it, is caused by car- rying too heavy loads on the head at too early an age. There seems to be a settling down of the body into the pelvis, with a loose alternate motion of the hips. There are exceptions, of course, and I have seen those of stately figure and fine carriage Sometimes the loose-hip motion appears in a man.

A slight tattooing appears on almost all Pima faces not of the last generation. In the women this consists of two blue lines running down from each corner of the mouth, under the chin, crossing, at the start, the lower lip, and a single blue line running back from the outer angle of each eye to the hair.

In the men it is usually a single zigzag blue line across the forehead.

The pigment used is charcoal.

The men are generally erect and of good figure, with good chests and rather heavy shoulders, the legs often a little bowed. Strange to say I never saw one who walked “Pigeon-toed.” All turned the toes out like white men. The hands are often small and almost always well-shaped; and the feet of good shape, too, not over large, with a well- arched instep.

Emory and his comrades found the Pimas wearing a kind of breech-cloth and a cotton serape only for gar- ments; the women wearing only a serape tied around the waist and falling to the knee, being otherwise nude. Today the average male Pima dresses like a white workman, in hat, shirt, trousers and perhaps shoes, and his wife or daughter wears a single print gown, rather loose at the waist and ruffled at the bottom, which reaches only to the ankles. Both sexes are commonly barefooted, but the old sandals, once universal, are still often seen. These gah-kai- gey-aht-kum-soosk, or string-shoes, as the word means, were made in several different ways, and often projected somewhat around the foot as a protection against the frequent and formidable thorns of the country.

Sometimes a wilder or older Indian will be seen, even now, with only a breech-cloth on, and some apology for a garment on his shoulders.

The skin is often of a very beautiful rich red-bronze tint, or perhaps more like old mahogany.

Except the tattooing both sexes are remarkable for their almost entire absence of any marked adornment or ornament of person. Even a finger-ring, or a ribbon on the hair, is not common, and the profuse bead-work and embroidery of the other tribes is never seen.

The exceedingly thick and intensely black hair was formerly worn very long, even to the waist, being banged off just over the eyes of the women and over the eyes and ears of the men and allowed to hang perfectly loose. But the women seldom wore: as long hair as the men. This long hair is still sometimes seen and is exceedingly pictur- esque, especially on horseback, and it is a great pity so sightly a fashion should ever die out. I have seen Maricopas roll theirs in ringlets. Sometimes the men braided the hair into a cue, or looped up the ends with a fillet. But the Government discourages long and loose hair, and now most men cut it short, and women part theirs and braid it. Like all Indians, the men have scant beards, and the few whiskers that grow are shaved clean or resolutely pinched off with an old knife or pulled out by tweezers.

Their hair appears to turn gray as early as ours, tho I saw no baldness except on one individual. In old times (and even now to some extent) the hair was dressed with a mixture of mud and mezquite gum, at times, which was left on long enough for the desired effect and then thoroly washed off. This cleansed it and made it glossy and the gum dyed the gray hair quite a lasting, jet black, tho several applications might be needed.

Women still carry their ollas and other burdens on their heads and are exceedingly strong and expert in the art, balancing great and awkward weights with admirable dexterity.

The convenient and even beautiful gyih-haw (a word very difficult to pronounce correctly), or burden basket, of the old time Pima woman, seems to have entirely disappeared. It was not only picturesque, but an exceedingly useful utensil.

The wawl-kote, or carrying-cradle for the baby, is obsolete, too, now. Strange to say, tho in shape like most pap- poose-cradles, it was carried poised on the head, instead of slung on the back in the usual way.

The Pimas are fond of conversation and often come together in the evening and have long talks. Their voices are low, rapid, soft and very pleasant and they laugh, smile and joke a great deal. They are remarkable for calmness and evenness of temper and the expression of the face is nearly always intelligent, frank, and good-natured.

They are noticeably devoid of hurry, worry, irritability or nervousness.

Unlike most Indians these have not been removed from the soil of their fathers and, indeed, such an act would have been cruelly unjust, for, true to their name, the Pimas have maintained an unbroken peace with the whites.

Lieutenant Colonel W. H. Emory, of “The Army of the West,” who visited them in 1846, was perhaps the first American to observe and describe these people. He says: “Both nations (Pimas and Maricopas) cherished an aver- sion to war and a profound attachment to all the peaceful pursuits of life. This predilection arose from no incapacity for war, for they were at all times able and willing to keep the Apaches, whose hands are raised against all other people, at a respectful distance, and prevent depredations by those mountain robbers who held Chihuahua, Sonora and a part of Durango in a condition approaching almost to tributary provinces.”

As observed by Emory and the other officers of the “Army of the West” they were an agricultural people rais- ing at that time “cotton, wheat, maize, beans, pumpkins and water melons.” I found them raising all these in 1903, except cotton, and I think he might have added to his list, peppers, gourds, tobacco and the pea called cah-lay-vahs.

Emory says: “We were at once impressed with the beauty, order, and disposition of the arrangements made for irrigating the land . . . the fields are subdivided by ridges of earth into rectangles of about 200×100 feet, for the con- venience of irrigating. The fences are of sticks, matted with willow and mezquite.” I found this still comparatively correct. The fields are still irrigated by acequias or ditches from the Gila, and still fenced by forks of trees set closely in the ground and reinforced with branches of thorn or barbed wire. Some of these fences with their antler-like effect of tops are very picturesque.

From the description given by Emory, and Captain A. R. Johnson of the same army, of their kees or winter lodges, they were essentially the same as I found some of them still inhabiting. There is the following entry in my journal: “I have been examining the old kee next door, since the old couple left it. It is quite neatly and systematical- ly made. Four large forks are set in the ground, and these support a square of large poles, covered with other poles, arrow-weeds, chaff and earth, for the roof. The walls are a neat arrangement of small saplings, about 10 inches apart curving up from the ground on a bending slant to the roof, so that the whole structure comes to resemble a turtle-shell or rather an inverted bowl. These side sticks arc connected by three lines of smaller sticks tied across them with withes, all the way around the kee. Against these arrow-weeds are stood, closely and neatly, tops down (perhaps thatched on) and kept in place by three more lines of small sticks, bound on and corresponding to those within. Then the whole structure is plastered over with adobe mud till rain-proof. No window, and only one small door, about 2½ feet square, closed by a slat-work.”

This kee of the Pima was not to his credit. The most friendly must admit it dirty, uncomfortable and unpictur- esque. It was too low to stand erect in, the little fire was made in the center, the smoke escaping at last from the low doorway after trying everywhere else and festooning the ceiling with soot.

The establishment of the Pima was most simple. He sat, ate and slept on the earth, consequently a few mats and blankets, baskets, bowls and pots included his furniture. A large earthen olla, called by the Pimas hah-ah, stood in a triple fork under the shade of the vachtoe and being porous enough to permit a slight evaporation kept the drinking water cool.

The arbor-shed or vachtoe pertains to almost every Piman home and consists of a flat roof of poles and ar- row-weeds supported by stout forks. Sometimes earth is added to the roof to keep off rain. Sometimes the sides are enclosed with a rude wattle work of weeds and bushes, making a grateful shade, admitting air freely; screening those within from view, while permitting vision from within outward in any direction. Sometimes this screen of weeds and bushes, in a circular form, was made without any roof and was then called an o-num. Sometimes after the vachtoe had been inclosed with wattle work the whole structure was plastered over with adobe mud and then became a caws-seen, or storehouse. All these structures were used at times as habitations, but now the Pima is com- ing more and more to the white man’s adobe cottage as a house and home. But the vachtoe, attached or detached, is still a feature of almost every homestead.

Under the vachtoe usually stood the matate, or mill (called by the Pimas mah-choot) which was a large flat or concave stone, below, across which was rubbed an oblong, narrow stone (vee-it-kote), above, to grind the corn or wheat. Other important utensils were a vatcheeho, or wooden trough, for mixing, and a chee-o-pah, or mortar, of wood or stone, for crushing things with a pestle. The nah-dah-kote, or fire-place, was an affair of stones and adobe mud to support the earthern pots for cooking or to support the earthern plates on which the thin cakes of corn or wheat meal were baked. These were what the Mexicans call tortillas. Perhaps the staple food of the Pima even more than corn (hohn) or wheat (payl-koon) is frijole beans—these of two kinds, the white (bah-fih) the brown (mohn). A sort of meal made of parched corn or wheat; ground on the mahchoot and eaten, or perhaps one might say drank, with water and brown sugar (panoche) was the famous pinole, the food carried on war trips when nutrition, light- ness of weight and smallness of bulk were all desired. It has a remarkable power to cool and quench thirst. Taw- mahls, or corn-cakes of ground green corn, wrapped in husks and roasted in the ashes, or boiled, were also favor- ites. Peppers (kaw-aw-kull) were a good deal used for seasoning and relishes.

Today the country of the Pima is very destitute of large game but he adds to the above bill of fare all the small game, especially rabbits, quail and doves, that he can kill. In the old days when the Gila always had water it held fine fish and the Indians caught them with their hands or swept them up on the banks by long chains of willow hurdles or faggots, carried around the fish by waders. I could not learn that they ever had any true fish-nets or fish-hooks; nor any rafts, canoes or other boats. But owing to the frequent necessity of crossing the treacherous Gila the men, and many of the women, were good swimmers.