The Decameron

Giovanni Boccaccio ( 13131375 C.E.)

Begun ca. 1349 and finished by 1353 C.E.

Italy

Boccaccio began writing his Decameron shortly after an outbreak of the plague in Florence, Italy, in 1348 that killed about three quarters of the population. The introduction to this frame tale depicts the horrors of the plague, with vivid descriptions of the dying and laments about the lack of a cure. In his story, seven women and three men leave Florence to take refuge in the countryside. They justify their decision in several ways: the right to self-preservation; the bad morals and lewd behavior of many of their neighbors (who are convinced that they are going to die anyway); and their own feelings of abandonment by their families. They decide to tell stories to pass the time: one story each for ten days (the Greek for “ten” is “deka” and for “day” is “hemera,” from which Boccaccio derives his title). Each day, one of them chooses a theme for the stories. As entertaining as the stories are, the discussions between the stories are what make the collection special; the speakers carry on a battle of the sexes as they debate the meaning and relative value of each story. The same dynamic can be found in two other frame tales in this anthology, one of which was influenced by the Decameron: the Thousand and One Nights (written before the Decameron) with its gripping frame story of Shahrazad; and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, with the conversations (and arguments) among the pilgrims who are telling the tales.

Written by Laura J. Getty

The Decameron

Giovanni Boccaccio, translated by John Payne

License: Public Domain

Introduction

To the Ladies

Giovanni Boccaccio, translated by Léopold Flameng

License: Public Domain

When I reflect how disposed you are by nature to compassion, I cannot help being apprehensive lest what I now offer to your acceptance should seem to have but a harsh and offensive beginning; for it presents at the very outset the mournful remembrance of that most fatal plague, so terrible yet in the memories of us all. But let not this dismay you from reading further, as though every page were to cost you sighs and tears. Rather let this beginning, disagreeable as it is, seem to you but as a rugged and steep mountain placed before a delightful valley, which appears more beautiful and pleasant, as the way to it was more difficult: for as joy usually ends in sorrow, so again the end of sorrow is joy. To this short fatigue (I call it short, because contained in few words,) immediately succeeds the mirth and pleasure I had before promised you; and which, but for that promise, you would scarcely expect to find. And in truth could I have brought you by any other way than this, I would gladly have done it: but as the occasion of the occurrences, of which I am going to treat, could not well be made out without such a relation, I am forced to use this Introduction.

In the year then of our Lord 1348, there happened at Florence, the finest city in all Italy, a most terrible plague; which, whether owing to the influence of the planets, or that it was sent from God as a just punishment for our sins, had broken out some years before in the Levant, and after passing from place to place, and making incredible havoc all the way, had now reached the west. There, spite of all the means that art and human foresight could suggest, such as keeping the city clear from filth, the exclusion of all suspected persons, and the publication of copious instructions for the preservation of health; and notwithstanding manifold humble supplications offered to God in processions and otherwise; it began to show itself in the spring of the aforesaid year, in a sad and wonderful manner. Unlike what had been seen in the east, where bleeding from the nose is the fatal prognostic, here there appeared certain tumours in the groin or under the arm-pits, some as big as a small apple, others as an egg; and afterwards purple spots in most parts of the body; in some cases large and but few in number, in others smaller and more numerous—both sorts the usual messengers of death. To the cure of this malady, neither medical knowledge nor the power of drugs was of any effect; whether because the disease was in its own nature mortal, or that the physicians (the number of whom, taking quacks and women pretenders into the account, was grown very great,) could form no just idea of the cause, nor consequently devise a true method of cure; whichever was the reason, few escaped; but nearly all died the third day from the first appearance of the symptoms, some sooner, some later, without any fever or other accessory symptoms. What gave the more virulence to this plague, was that, by being communicated from the sick to the hale, it spread daily, like fire when it comes in contact with large masses of combustibles. Nor was it caught only by conversing with, or coming near the sick, but even by touching their clothes, or anything that they had before touched. It is wonderful, what I am going to mention; and had I not seen it with my own eyes, and were there not many witnesses to attest it besides myself, I should never venture to relate it, however worthy it were of belief. Such, I say, was the quality of the pestilential matter, as to pass not only from man to man, but, what is more strange, it has been often known, that anything belonging to the infected, if touched by any other creature, would certainly infect, and even kill that creature in a short space of time. One instance of this kind I took particular notice of: the rags of a poor man just dead had been thrown into the street; two hogs came up, and after rooting amongst the rags, and shaking them about in their mouths, in less than an hour they both turned round, and died on the spot.

These facts, and others of the like sort, occasioned various fears and devices amongst those who survived, all tending to the same uncharitable and cruel end; which was, to avoid the sick, and everything that had been near them, expecting by that means to save themselves. And some holding it best to live temperately, and to avoid excesses of all kinds, made parties, and shut themselves up from the rest of the world; eating and drinking moderately of the best, and diverting themselves with music, and such other entertainments as they might have within door; never listening to anything from without, to make them uneasy. Others maintained free living to be a better preservative, and would baulk no passion or appetite they wished to gratify, drinking and reveling incessantly from tavern to tavern, or in private houses (which were frequently found deserted by the owners, and therefore common to every one), yet strenuously avoiding, with all this brutal indulgence, to come near the infected. And such, at that time, was the public distress, that the laws, human and divine, were no more regarded; for the officers, to put them in force, being either dead, sick, or in want of persons to assist them, every one did just as he pleased. A third sort of people chose a method between these two: not confining themselves to rules of diet like the former, and yet avoiding the intemperance of the latter ; but eating and drinking what their appetites required, they walked everywhere with odours and nose gays to smell to ; as holding it best to corroborate the brain: for the whole atmosphere seemed to them tainted with the stench of dead bodies, arising partly from the distemper itself, and partly from the fermenting of the medicines within them. Others with less humanity, but perchance, as they supposed, with more security from danger, decided that the only remedy for the pestilence was to avoid it: persuaded, therefore, of this, and taking care for themselves only, men and women in great numbers left the city, their houses, relations, and effects, and fled into the country: as if the wrath of God had been restrained to visit those only within the walls of the city; or else concluding, that none ought to stay in a place thus doomed to destruction.

Thus divided as they were in their views, neither did all die, nor all escape; but falling sick indifferently, as well those of one as of another opinion; they who first set the example by forsaking others, now languished themselves without pity. I pass over the little regard that citizens and relations showed to each other; for their terror was such, that a brother even fled from his brother, a wife from her husband, and, what is more uncommon, a parent from his own child. Hence numbers that fell sick could have no help but what the charity of friends, who were very few, or the avarice of servants supplied; and even these were scarce and at extravagant wages, and so little used to the business that they were fit only to reach what was called for, and observe when their employer died; and this desire of getting money often cost them their lives. From this desertion of friends, and scarcity of servants, an unheard-of custom prevailed; no lady, however young or handsome, would scruple to be attended by a man-servant, whether young or old it mattered not, and to expose herself naked to him, the necessity of the distemper requiring it, as though it was to a woman; which might make those who recovered, less modest for the time to come. And many lost their lives, who might have escaped, had they been looked after at all. So that, between the scarcity of servants, and the violence of the distemper, such numbers were continually dying, as made it terrible to hear as well as to behold. Whence, from mere necessity, many customs were introduced different from what had been before known in the city.

It had been usual, as it now is, for the women who were friends and neighbours to the deceased, to meet together at his house, and to lament with his relations; at the same time the men would get together at the door, with a number of clergy, according to the person’s circumstances; and the corpse was carried by people of his own rank, with the solemnity of tapers and singing, to that church where the deceased had desired to be buried. This custom was now laid aside, and, so far from having a crowd of women to lament over them, great numbers passed out of the world without a witness. Few were they who had the tears of their friends at their departure; those friends were laughing and making themselves merry the while; for even the women had learned to postpone every other concern to that of their own lives. Nor was a corpse attended by more than ten or a dozen, nor those citizens of credit, but fellows hired for the purpose; who would put themselves under the bier, and carry it with all possible haste to the nearest church; and the corpse was interred, without any great ceremony, where they could find room. With regard to the lower sort, and many of a middling rank, the scene was still more affecting; for they staying at home either through poverty or hopes of succour in distress, fell sick daily by thousands, and, having nobody to attend them, generally died: some breathed their last in the streets, and others shut up in their own houses, where the stench that came from them made the first discovery of their deaths to the neighbourhood. And, indeed, every place was filled with the dead. Hence it became a general practice, as well out of regard for the living as pity for the dead, for the neighbours, assisted by what porters they could meet with, to clear all the houses, and lay the bodies at the doors; and every morning great numbers might be seen brought out in this manner, to be carried away on biers, or tables, two or three at a time; and sometimes it has happened that a wife and her husband, two or three brothers, and a father and son, have been laid on together. It has been observed also, whilst two or three priests have walked before a corpse with their crucifix, that two or three sets of porters have fallen in with them; and where they knew but of one dead body, they have buried six, eight, or more : nor was there any to follow, and shed a few tears over them ; for things were come to that pass, that men’s lives were no more regarded than the lives of so many beasts. Thus it plainly appeared, that what the wisest in the ordinary course of things, and by a common train of calamities, could never be taught, namely, to bear them patiently, this, by the excess of calamity, was now grown a familiar lesson to the most simple and unthinking. The consecrated ground no longer containing the numbers which were continually brought thither, especially as they were desirous of laying every one in the parts allotted to their families, they were forced to dig trenches, and to put them in by hundreds, piling them up in rows, as goods are stowed in a ship, and throwing in a little earth till they were filled to the top.

Not to dwell upon every particular of our misery, I shall observe, that it fared no better with the adjacent country; for, to omit the different boroughs about us, which presented the same view in miniature with the city, you might see the poor distressed labourers, with their families, without either the aid of physicians, or help of servants, languishing on the highways, in the fields, and in their own houses, and dying rather like cattle than human creatures. The consequence was that, growing dissolute in their manners like the citizens, and careless of everything, as supposing every day to be their last, their thoughts were not so much employed how to improve, as how to use their substance for their present support. The oxen, asses, sheep, goats, swine, and the dogs themselves, ever faithful to their masters, being driven from their own homes, were left to roam at will about the fields, and among the standing corn, which no one cared to gather, or even to reap ; and many times, after they had filled themselves in the day, the animals would return of their own accord like rational creatures at night.

What can I say more, if I return to the city? Unless that such was the cruelty of Heaven, and perhaps of men, that between March and July following, according to authentic reckonings, upwards of a hundred thousand souls perished in the city only; whereas, before that calamity, it was not supposed to have contained so many inhabitants. What magnificent dwellings, what noble palaces were then depopulated to the last inhabitant! What families became extinct! What riches and vast possessions were left, and no known heir to inherit them! What numbers of both sexes, in the prime and vigour of youth, whom in the morning neither Galen, Hippocrates, nor Æsculapius himself, would have denied to be in perfect health, breakfasted in the morning with their living friends, and supped at night with their departed friends in the other world or else to show by our habits the greatness of our distress. And if we go hence, it is either to see multitudes of the dead and sick carried along the streets; or persons who had been outlawed for their villanies, now facing it out publicly, in safe defiance of the laws; or the scum of the city, enriched with the public calamity, and insulting us with ribald ballads. Nor is anything now talked of, but that such a one is dead, or dying; and, were any left to mourn, we should hear nothing but lamentations. Or if we go home — I know not whether it fares with you as with myself—when I find out of a numerous family not one left besides a maidservant, I am frightened out of my senses; and go where I will, the ghosts of the departed seem always before me; not like the persons whilst they were living, but assuming a ghastly and dreadful aspect. Therefore the case is the same, whether we stay here, depart hence, or go home; especially as there are few left but ourselves who are able to go, and have a place to go to. Those few too, I am told, fall into all sorts of debauchery; and even cloistered ladies, supposing themselves entitled to equal liberties with others, are as bad as the worst. Now if this be so (as you see plainly it is), what do we here? What are we dreaming of? Why are we less regardful of our lives than other people of theirs? Are we of less value to ourselves, or are our souls and bodies more firmly united, and so in less danger of dissolution? It is monstrous to think in such a manner; so many of both sexes dying of this distemper in the very prime of their youth afford us an undeniable argument to the contrary. Wherefore, lest through our own willfulness or neglect, this calamity, which might have been prevented, should befall us, I should think it best (and I hope you will join with me,) for us to quit the town, and avoiding, as we would death itself, the bad example of others, to choose some place of retirement, of which every one of us has more than one, where we may make ourselves innocently merry, without offering the least violence to the dictates of reason and our own consciences. There will our ears be entertained with the warbling of the birds, and our eyes with the verdure of the hills and valleys; with the waving of cornfields like the sea itself; with trees of a thousand different kinds, and a more open and serene sky; which, however overcast, yet affords a far more agreeable prospect than these desolate walls. The air also is pleasanter, and there is greater plenty of everything, attended with few inconveniences: for, though people die there as well as here, yet we shall have fewer such objects before us, as the inhabitants are less in number; and on the other part, if I judge right, we desert nobody, but are rather ourselves forsaken. For all our friends, either by death, or endeavouring to avoid it, have left us, as if we in no way belonged to them. As no blame then can ensue from following this advice, and perhaps sickness and death from not doing so, I would have us take our maids, and everything we may be supposed to want, and enjoy all the diversions which the season will permit, to-day in one place, to-morrow in another; and so continue to do, unless death should interpose, until we see what end Providence designs for these things. And of this too let me remind you, that our characters will stand as fair by our going away reputably, as those of others will do who stay at home with discredit.”

The ladies having heard what Pampinea had to offer, not only approved of it, but had actually began to concert measures for their instant departure, when Filomena, who was a most discreet person, remarked: “Though Pampinea has spoken well, yet there is no occasion to run headlong into the affair, as you are about to do. We are but women, nor is any of us so ignorant as not to know how little able we shall be to conduct such an affair, without some man to help us. We are naturally fickle, obstinate, suspicious, and fearful; and I doubt much, unless we take somebody into our scheme to manage it for us, lest it soon be at an end; and perhaps, little to our reputation. Let us provide against this, therefore, before we begin.”

Eliza then replied: “It is true, man is our sex’s chief or head, and without his management, it seldom happens that any undertaking of ours succeeds well. But how are these men to be come at? We all know that the greater part of our male acquaintance are dead, and the rest all dispersed abroad, avoiding what we seek to avoid, and without our knowing where to find them. To take strangers with us, would not be altogether so proper: for, whilst we have regard to our health, we should so contrive matters, that, wherever we go to repose and divert ourselves, no scandal may ensue from it.”

Whilst this matter was in debate, behold, three gentlemen came into the church, the youngest not less than twenty-five years of age, and in whom neither the adversity of the times, the loss of relations and friends, nor even fear for themselves, could stifle, or indeed cool, the passion of love. One was called Pamfilo, the second Filostrato, and the third Dioneo, all of them well bred, and pleasant companions; and who, to divert themselves in this time of affliction, were then in pursuit of their mistresses, who as it chanced were three of these seven ladies, the other four being all related to one or other of them. These gentlemen were no sooner within view, than the ladies had immediately their eyes upon them, and Pampinea said, with a smile, “See, fortune is with us, and has thrown in our way three prudent and worthy gentlemen, who will conduct and wait upon us, if we think fit to accept of their service.” Neifile, with a blush, because she was one that had an admirer, answered: “Take care what you say, I know them all indeed to be persons of character, and fit to be trusted, even in affairs of more consequence, and in better company; but, as some of them are enamoured of certain ladies here, I am only concerned lest we be drawn into some scrape or scandal, without either our fault or theirs.” Filomena replied: “Never tell me what other people may think, so long as I know myself to be virtuous; God and the truth will be my defence; and if they be willing to go, we will say with Pampinea, that fortune is with us.”

The rest hearing her speak in this manner, gave consent that the gentlemen should be invited to partake in this expedition. Without more words, Pampinea, who was related to one of the three rose up, and made towards them, as they stood watching at a distance. Then, after a cheerful salutation, she acquainted them with the design in hand, and entreated that they would, out of pure friendship, oblige them with their company. The gentlemen at first took it all for a jest, but, being assured to the contrary, immediately answered that they were ready; and, to lose no time, gave the necessary orders for what they wished to have done. Every thing being thus prepared, and a messenger dispatched before, whither they intended to go, the next morning, which was Wednesday, by break of day, the ladies, with some of their women, and the gentlemen, with every one his servant, set out from the city, and, after they had travelled two short miles, came to the place appointed.

It was a little eminence, remote from any great road, covered with trees and shrubs of an agreeable verdure; and on the top was a stately palace, with a grand and beautiful court in the middle: within were galleries, and fine apartments elegantly fitted up, and adorned with most curious paintings; around it were fine meadows, and most delightful gardens, with fountains of the purest and best water. The vaults also were stored with the richest wines, suited rather to the taste of copious topers, than of modest and virtuous ladies. This palace they found cleared out, and everything set in order for their reception, with the rooms all graced with the flowers of the season, to their great satisfaction. The party being seated, Dioneo, who was the pleasantest of them all, and full of words, began “Your wisdom it is, ladies, rather than any foresight of ours, which has brought us hither. I know not how you have disposed of your cares; as for mine, I left them all behind me when I came from home. Either prepare, then, to be as merry as myself (I mean with decency), or give me leave to go back again, and resume my cares where I left them.” Pampinea made answer, as if she had disposed of hers in like manner: “You say right, sir, we will be merry; we fled from our troubles for no other reason. But, as extremes are never likely to last, I, who first proposed the means by which such an agreeable company is now met together, being desirous to make our mirth of some continuance, do find there is a necessity for our appointing a principal, whom we shall honour and obey in all things as our head; and whose province it shall be to regulate our diversions. And that every one may make trial of the burthen which attends care, as well as the pleasure which there is in superiority, nor therefore envy what he has not yet tried, I hold it best that every one should experience both the trouble and the honour for one day. The first, I propose, shall be elected by us all, and, on the approach of evening, hall name a person to succeed for the following day: and each one, during the time of his or her government, shall give orders concerning the place where, and the manner how, we are to live.”

These words were received with the highest satisfaction, and the speaker was, with one consent, appointed president for the first day: whilst Filomena, running to a laurel-tree, (for she had often heard how much that tree has always been esteemed, and what honour was conferred on those who were deservedly crowned with it,) made a garland, and put it upon Pampinea’s head. That garland, whilst the company continued together, was ever after to be the ensign of sovereignty.

Pampinea, being thus elected queen, enjoined silence, and having summoned to her presence the gentlemen’s servants, and their own women, who were four in number: “To give you the first example,” said she, “how, by proceeding from good to better, we may live orderly and pleasantly, and continue together, without the least reproach, as long as we please, in the first place I declare Parmeno, Dioneo’s servant, master of my household, and to him I commit the care of my family, and everything relating to my hall. Sirisco, Pamfilo’s servant, I appoint my treasurer, and to be under the direction of Parmeno; and Tindaro I command to wait on Filostrato and the other two gentlemen, whilst their servants are thus employed. Mysia, my woman, and Licisca, Filomena’s, I order into the kitchen, there to get ready what shall be provided by Parmeno. To Lauretta’s Chimera, and Fiammetta’s Stratilia, I give the care of the ladies’ chambers, and to keep the room clean where we sit. And I will and command you all, on pain of my displeasure, that wherever you go, or whatever you hear and see, you bring no news here but what is good.” These orders were approved by all; and the queen, rising from her seat, with a good deal of gaiety, added: “Here are gardens and meadows, where you may divert yourselves till nine o’clock, when I shall expect you back, that we may dine in the cool of the day.”

The company were now at liberty, and the gentlemen and ladies took a pleasant walk in the garden, talking over a thousand merry things by the way, and diverting themselves by singing love songs, and weaving garlands of flowers. Returning at the time appointed, they found Parmeno busy in the execution of his office: for in a saloon below was the table set forth, covered with the neatest linen, with glasses reflecting a lustre like silver: and water having been presented to them to wash their hands, by the queen’s order, Parmeno desired them to sit down. The dishes were now served up in the most elegant manner, and the best wines brought in, the servants waiting all the time with the most profound silence; and being well pleased with their entertainment, they dined with all the facetiousness and mirth imaginable. When dinner was over, as they could all dance, and some both play and sing well, the queen ordered in the musical instruments. Dioneo took a lute, and Fiammetta a viol, in obedience to the royal command; a dance was struck up, and the queen, with the rest of the company, took an agreeable turn or two, whilst the servants were sent to dinner; and when the dance was ended, they began to sing, and continued till the queen thought it time to break up. Her permission being given, the gentlemen retired to their chambers, remote from the ladies’ lodging rooms, and the ladies did the same, and undressed themselves for bed.

It was little more than three, when the queen rose, and ordered all to be called, alleging that much sleep in the daytime was unwholesome. Then they went into a meadow of deep grass, where the sun had little power; and having the benefit of a pleasant breeze, they sat down in a circle, as the queen had commanded, and she addressed them in this manner:—“As the sun is high, and the heat excessive, and nothing is to be heard but the chirping of the cicalas among the olives, it would be madness for us to think of moving yet: this is an airy place, and here are chess-boards and backgammon tables to divert yourselves with; but if you will be ruled by me, you will not play at all, since it often makes the one party uneasy, without any great pleasure to the other, or to the lookers-on; but let us begin and tell stories, and in this manner one person will entertain the whole company ; and by the time it has gone round, the worst part of the day will be over, and then we can divert ourselves as we like best. If this be agreeable to you, then (for I wait to know your pleasure) let us begin; if not, you are at your own disposal till the evening.” This motion being approved by all, the queen continued, “Let every one for this first day take what subject he fancies most:” and turning to Pamfilo, who sat on her right hand, she bade him begin. He readily obeyed, and spoke to this effect, so as to be distinctly heard by the whole company.

Day the Third

The Ninth Story

Gillette de narbonne recovereth the king of france of a fistula and demandeth for her husband bertrand de roussillon, who marrieth her against his will and betaketh him for despite to florence, where, he paying court to a young lady, gillette, in the person of the latter, lieth with him and hath by him two sons; wherefore after, holding her dear, he entertaineth her for his wife.

Lauretta’s story being now ended, it rested but with the queen to tell, an she would not infringe upon Dioneo’s privilege; wherefore, without waiting to be solicited by her companions, she began all blithesomely to speak thus: “Who shall tell a story that may appear goodly, now we have heard that of Lauretta? Certes, it was well for us that hers was not the first, for that few of the others would have pleased after it, as I misdoubt me will betide of those which are yet to tell this day. Natheless, be that as it may, I will e’en recount to you that which occurreth to me upon the proposed theme.

There was in the kingdom of France a gentleman called Isnard, Count of Roussillon, who, for that he was scant of health, still entertained about his person a physician, by name Master Gerard de Narbonne. The said count had one little son, and no more, hight Bertrand, who was exceeding handsome and agreeable, and with him other children of his own age were brought up. Among these latter was a daughter of the aforesaid physician, by name Gillette, who vowed to the said Bertrand an infinite love and fervent more than pertained unto her tender years. The count dying and leaving his son in the hands of the king, it behoved him betake himself to Paris, whereof the damsel abode sore disconsolate, and her own father dying no great while after, she would fain, an she might have had a seemly occasion, have gone to Paris to see Bertrand: but, being straitly guarded, for that she was left rich and alone, she saw no honourable way thereto; and being now of age for a husband and having never been able to forget Bertrand, she had, without reason assigned, refused many to whom her kinsfolk would have married her.

Now it befell that, what while she burned more than ever for love of Bertrand, for that she heard he was grown a very goodly gentleman, news came to her how the King of France, by an imposthume which he had had in his breast and which had been ill tended, had gotten a fistula, which occasioned him the utmost anguish and annoy, nor had he yet been able to find a physician who might avail to recover him thereof, albeit many had essayed it, but all had aggravated the ill; wherefore the king, despairing of cure, would have no more counsel nor aid of any. Hereof the young lady was beyond measure content and bethought herself that not only would this furnish her with a legitimate occasion of going to Paris, but that, should the king’s ailment be such as she believed, she might lightly avail to have Bertrand to husband. Accordingly, having aforetime learned many things of her father, she made a powder of certain simples useful for such an infirmity as she conceived the king’s to be and taking horse, repaired to Paris.

Before aught else she studied to see Bertrand and next, presenting herself before the king, she prayed him of his favour to show her his ailment. The king, seeing her a fair and engaging damsel, knew not how to deny her and showed her that which ailed him. Whenas she saw it, she was certified incontinent that she could heal it and accordingly said, ‘My lord, an it please you, I hope in God to make you whole of this your infirmity in eight days’ time, without annoy or fatigue on your part.’ The king scoffed in himself at her words, saying, ‘That which the best physicians in the world have availed not neither known to do, how shall a young woman know?’ Accordingly, he thanked her for her good will and answered that he was resolved no more to follow the counsel of physicians. Whereupon quoth the damsel, ‘My lord, you make light of my skill, for that I am young and a woman; but I would have you bear in mind that I medicine not of mine own science, but with the aid of God and the science of Master Gerard de Narbonne, who was my father and a famous physician whilst he lived.’

The king, hearing this, said in himself, ‘It may be this woman is sent me of God; why should I not make proof of her knowledge, since she saith she will, without annoy of mine, cure me in little time?’ Accordingly, being resolved to essay her, he said, ‘Damsel, and if you cure us not, after causing us break our resolution, what will you have ensue to you therefor?’ ‘My lord,’ answered she, ‘set a guard upon me and if I cure you not within eight days, let burn me alive; but, if I cure you, what reward shall I have?’ Quoth the king, ‘You seem as yet unhusbanded; if you do this, we will marry you well and worshipfully.’ ‘My lord,’ replied the young lady, ‘I am well pleased that you should marry me, but I will have a husband such as I shall ask of you, excepting always any one of your sons or of the royal house.’ He readily promised her that which she sought, whereupon she began her cure and in brief, before the term limited, she brought him back to health.

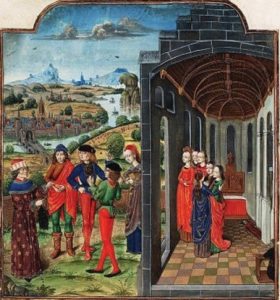

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: Public Domain

The king, feeling himself healed, said, ‘Damsel, you have well earned your husband’; whereto she answered, ‘Then, my lord, I have earned Bertrand de Roussillon, whom I began to love even in the days of my childhood and have ever since loved over all.’ The king deemed it a grave matter to give him to her; nevertheless, having promised her and unwilling to fail of his faith, he let call the count to himself and bespoke him thus: ‘Bertrand, you are now of age and accomplished [in all that behoveth unto man’s estate]; wherefore it is our pleasure that you return to govern your county and carry with you a damsel, whom we have given you to wife.’ ‘And who is the damsel, my lord?’ asked Bertrand; to which the king answered, ‘It is she who hath with her medicines restored to us our health.’

Bertrand, who had seen and recognized Gillette, knowing her (albeit she seemed to him very fair) to be of no such lineage as sorted with his quality, said all disdainfully, ‘My lord, will you then marry me to a she-leach? Now God forbid I should ever take such an one to wife!’ ‘Then,’ said the king, ‘will you have us fail of our faith, the which, to have our health again, we pledged to the damsel, who in guerdon thereof demanded you to husband?’ ‘My lord,’ answered Bertrand, ‘you may, an you will, take from me whatsoever I possess or, as your liegeman, bestow me upon whoso pleaseth you; but of this I certify you, that I will never be a consenting party unto such a marriage.’ ‘Nay,’ rejoined the king, ‘but you shall, for that the damsel is fair and wise and loveth you dear; wherefore we doubt not but you will have a far happier life with her than with a lady of higher lineage.’ Bertrand held his peace and the king let make great preparations for the celebration of the marriage.

The appointed day being come, Bertrand, sore against his will, in the presence of the king, espoused the damsel, who loved him more than herself. This done, having already determined in himself what he should do, he sought leave of the king to depart, saying he would fain return to his county and there consummate the marriage; then, taking horse, he repaired not thither, but betook himself into Tuscany, where, hearing that the Florentines were at war with those of Sienna, he determined to join himself to the former, by whom he was joyfully received and made captain over a certain number of men-at-arms; and there, being well provided of them, he abode a pretty while in their service.

The newly-made wife, ill content with such a lot, but hoping by her fair dealing to recall him to his county, betook herself to Roussillon, where she was received of all as their liege lady. There, finding everything waste and disordered for the long time that the land had been without a lord, with great diligence and solicitude, like a discreet lady as she was, she set all in order again, whereof the count’s vassals were mightily content and held her exceeding dear, vowing her a great love and blaming the count sore for that he accepted not of her. The lady, having thoroughly ordered the county, notified the count thereof by two knights, whom she despatched to him, praying him that, an it were on her account he forbore to come to his county, he should signify it to her and she, to pleasure him, would depart thence; but he answered them very harshly, saying, ‘For that, let her do her pleasure; I, for my part, will return thither to abide with her, whenas she shall have this my ring on her finger and in her arms a son by me begotten.’ Now the ring in question he held very dear and never parted with it, by reason of a certain virtue which it had been given him to understand that it had.

The knights understood the hardship of the condition implied in these two well nigh impossible requirements, but, seeing that they might not by their words avail to move him from his purpose, they returned to the lady and reported to her his reply; whereat she was sore afflicted and determined, after long consideration, to seek to learn if and where the two things aforesaid might be compassed, to the intent that she might, in consequence, have her husband again. Accordingly, having bethought herself what she should do, she assembled certain of the best and chiefest men of the county and with plaintive speech very orderly recounted to them that which she had already done for love of the count and showed them what had ensued thereof, adding that it was not her intent that, through her sojourn there, the count should abide in perpetual exile; nay, rather she purposed to spend the rest of her life in pilgrimages and works of mercy and charity for her soul’s health; wherefore she prayed them take the ward and governance of the county and notify the count that she had left him free and vacant possession and had departed the country, intending nevermore to return to Roussillon. Many were the tears shed by the good folk, whilst she spoke, and many the prayers addressed to her that it would please her change counsel and abide there; but they availed nought. Then, commending them to God, she set out upon her way, without telling any whither she was bound, well furnished with monies and jewels of price and accompanied by a cousin of hers and a chamberwoman, all in pilgrims’ habits, and stayed not till she came to Florence, where, chancing upon a little inn, kept by a decent widow woman, she there took up her abode and lived quietly, after the fashion of a poor pilgrim, impatient to hear news of her lord.

It befell, then, that on the morrow of her arrival she saw Bertrand pass before her lodging, a-horseback with his company, and albeit she knew him full well, natheless she asked the good woman of the inn who he was. The hostess answered, ‘That is a stranger gentleman, who calleth himself Count Bertrand, a pleasant man and a courteous and much loved in this city; and he is the most enamoured man in the world of a she-neighbour of ours, who is a gentlewoman, but poor. Sooth to say, she is a very virtuous damsel and abideth, being yet unmarried for poverty, with her mother, a very good and discreet lady, but for whom, maybe, she had already done the count’s pleasure.’ The countess took good note of what she heard and having more closely enquired into every particular and apprehended all aright, determined in herself how she should do.

Accordingly, having learned the house and name of the lady whose daughter the count loved, she one day repaired privily thither in her pilgrim’s habit and finding the mother and daughter in very poor case, saluted them and told the former that, an it pleased her, she would fain speak with her alone. The gentlewoman, rising, replied that she was ready to hearken to her and accordingly carried her into a chamber of hers, where they seated themselves and the countess began thus, ‘Madam, meseemeth you are of the enemies of Fortune, even as I am; but, an you will, belike you may be able to relieve both yourself and me.’ The lady answered that she desired nothing better than to relieve herself by any honest means; and the countess went on, ‘Needs must you pledge me your faith, whereto an I commit myself and you deceive me, you will mar your own affairs and mine.’ ‘Tell me anything you will in all assurance,’ replied the gentlewoman; ‘for never shall you find yourself deceived of me.’

Thereupon the countess, beginning with her first enamourment, recounted to her who she was and all that had betided her to that day after such a fashion that the gentlewoman, putting faith in her words and having, indeed, already in part heard her story from others, began to have compassion of her. The countess, having related her adventures, went on to say, ‘You have now, amongst my other troubles, heard what are the two things which it behoveth me have, an I would have my husband, and to which I know none who can help me, save only yourself, if that be true which I hear, to wit, that the count my husband is passionately enamoured of your daughter.’ ‘Madam,’ answered the gentlewoman, ‘if the count love my daughter I know not; indeed he maketh a great show thereof. But, an it be so, what can I do in this that you desire?’ ‘Madam,’ rejoined the countess, ‘I will tell you; but first I will e’en show you what I purpose shall ensue thereof to you, an you serve me. I see your daughter fair and of age for a husband and according to what I have heard, meseemeth I understand the lack of good to marry her withal it is that causeth you keep her at home. Now I purpose, in requital of the service you shall do me, to give her forthright of mine own monies such a dowry as you yourself shall deem necessary to marry her honorably.’

The mother, being needy, was pleased with the offer; algates, having the spirit of a gentlewoman, she said, ‘Madam, tell me what I can do for you; if it consist with my honour, I will willingly do it, and you shall after do that which shall please you.’ Then said the countess, ‘It behoveth me that you let tell the count my husband by some one in whom you trust, that your daughter is ready to do his every pleasure, so she may but be certified that he loveth her as he pretendeth, the which she will never believe, except he send her the ring which he carrieth on his finger and by which she hath heard he setteth such store. An he send you the ring, you must give it to me and after send to him to say that your daughter is ready do his pleasure; then bring him hither in secret and privily put me to bed to him in the stead of your daughter. It may be God will vouchsafe me to conceive and on this wise, having his ring on my finger and a child in mine arms of him begotten, I shall presently regain him and abide with him, as a wife should abide with her husband, and you will have been the cause thereof.’

This seemed a grave matter to the gentlewoman, who feared lest blame should haply ensue thereof to her daughter; nevertheless, bethinking her it were honourably done to help the poor lady recover her husband and that she went about to do this to a worthy end and trusting in the good and honest intention of the countess, she not only promised her to do it, but, before many days, dealing with prudence and secrecy, in accordance with the latter’s instructions, she both got the ring (albeit this seemed somewhat grievous to the count) and adroitly put her to bed with her husband, in the place of her own daughter. In these first embracements, most ardently sought of the count, the lady, by God’s pleasure, became with child of two sons, as her delivery in due time made manifest. Nor once only, but many times, did the gentlewoman gratify the countess with her husband’s embraces, contriving so secretly that never was a word known of the matter, whilst the count still believed himself to have been, not with his wife, but with her whom he loved; and whenas he came to take leave of a morning, he gave her, at one time and another, divers goodly and precious jewels, which the countess laid up with all diligence.

Then, feeling herself with child and unwilling to burden the gentlewoman farther with such an office, she said to her, ‘Madam, thanks to God and you, I have gotten that which I desired, wherefore it is time that I do that which shall content you and after get me gone hence.’ The gentlewoman answered that, if she had gotten that which contented her, she was well pleased, but that she had not done this of any hope of reward, nay, for that herseemed it behoved her to do it, an she would do well. ‘Madam,’ rejoined the countess, ‘that which you say liketh me well and so on my part I purpose not to give you that which you shall ask of me by way of reward, but to do well, for that meseemeth behoveful so to do.’ The gentlewoman, then, constrained by necessity, with the utmost shamefastness, asked her an hundred pounds to marry her daughter withal; but the countess, seeing her confusion and hearing her modest demand, gave her five hundred and so many rare and precious jewels as were worth maybe as much more. With this the gentlewoman was far more than satisfied and rendered the countess the best thanks in her power; whereupon the latter, taking leave of her, returned to the inn, whilst the other, to deprive Bertrand of all farther occasion of coming or sending to her house, removed with her daughter into the country to the house of one of her kinsfolk, and he, being a little after recalled by his vassals and hearing that the countess had departed the country, returned to his own house.

Author: Raffaello Sanzio Morghen

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: Public Domain

The countess, hearing that he had departed Florence and returned to his county, was mightily rejoiced and abode at Florence till her time came to be delivered, when she gave birth to two male children, most like their father, and let rear them with all diligence. Whenas it seemed to her time, she set out and came, without being known of any, to Montpellier, where having rested some days and made enquiry of the count and where he was, she learned that he was to hold a great entertainment of knights and ladies at Roussillon on All Saints’ Day and betook herself thither, still in her pilgrim’s habit that she was wont to wear. Finding the knights and ladies assembled in the count’s palace and about to sit down to table, she went up, with her children in her arms and without changing her dress, into the banqueting hall and making her way between man and man whereas she saw the count, cast herself at his feet and said, weeping, ‘I am thine unhappy wife, who, to let thee return and abide in thy house, have long gone wandering miserably about the world. I conjure thee, in the name of God, to accomplish unto me thy promise upon the condition appointed me by the two knights I sent thee; for, behold, here in mine arms is not only one son of thine, but two, and here is thy ring. It is time, then, that I be received of thee as a wife, according to thy promise.’

The count, hearing this, was all confounded and recognized the ring and the children also, so like were they to him; but yet he said, ‘How can this have come to pass?’ The countess, then, to his exceeding wonderment and that of all others who were present, orderly recounted that which had passed and how it had happened; whereupon the count, feeling that she spoke sooth and seeing her constancy and wit and moreover two such goodly children, as well for the observance of his promise as to pleasure all his liegemen and the ladies, who all besought him thenceforth to receive and honour her as his lawful wife, put off his obstinate despite and raising the countess to her feet, embraced her and kissing her, acknowledged her for his lawful wife and those for his children. Then, letting clothe her in apparel such as beseemed her quality, to the exceeding joyance of as many as were there and of all other his vassals who heard the news, he held high festival, not only all that day, but sundry others, and from that day forth still honoured her as his bride and his wife and loved and tendered her over all.”

Day the Fourth

The Second Story

Fra alberto giveth a lady to believe that the angel gabriel is enamoured of her and in his shape lieth with her sundry times; after which, for fear of her kinsmen, he casteth himself forth of her window into the canal and taketh refuge in the house of a poor man, who on the morrow carrieth him, in the guise of a wild man of the woods, to the piazza, where, being recognized, he is taken by his brethren and put in prison.

The story told by Fiammetta had more than once brought the tears to the eyes of the ladies her companions; but, it being now finished, the king with a stern countenance said, “My life would seem to me a little price to give for half the delight that Guiscardo had with Ghismonda, nor should any of you ladies marvel thereat, seeing that every hour of my life I suffer a thousand deaths, nor for all that is a single particle of delight vouchsafed me. But, leaving be my affairs for the present, it is my pleasure that Pampinea follow on the order of the discourse with some story of woeful chances and fortunes in part like to mine own; which if she ensue like as Fiammetta hath begun, I shall doubtless begin to feel some dew fallen upon my fire.” Pampinea, hearing the order laid upon her, more by her affection apprehended the mind of the ladies her companions than that of Filostrato by his words, wherefore, being more disposed to give them some diversion than to content the king, farther than in the mere letter of his commandment, she bethought herself to tell a story, that should, without departing from the proposed theme, give occasion for laughter, and accordingly began as follows:

“The vulgar have a proverb to the effect that he who is naught and is held good may do ill and it is not believed of him; the which affordeth me ample matter for discourse upon that which hath been proposed to me and at the same time to show what and how great is the hypocrisy of the clergy, who, with garments long and wide and faces paled by art and voices humble and meek to solicit the folk, but exceeding loud and fierce to rebuke in others their own vices, pretend that themselves by taking and others by giving to them come to salvation, and to boot, not as men who have, like ourselves, to purchase paradise, but as in a manner they were possessors and lords thereof, assign unto each who dieth, according to the sum of the monies left them by him, a more or less excellent place there, studying thus to deceive first themselves, an they believe as they say, and after those who put faith for that matter in their words. Anent whom, were it permitted me to discover as much as it behoved, I would quickly make clear to many simple folk that which they keep hidden under those huge wide gowns of theirs. But would God it might betide them all of their cozening tricks, as it betided a certain minor friar, and he no youngling, but held one of the first casuists in Venice; of whom it especially pleaseth me to tell you, so as peradventure somewhat to cheer your hearts, that are full of compassion for the death of Ghismonda, with laughter and pleasance.

There was, then, noble ladies, in Imola, a man of wicked and corrupt life, who was called Berto della Massa and whose lewd fashions, being well known of the Imolese, had brought him into such ill savour with them that there was none in the town who would credit him, even when he said sooth; wherefore, seeing that his shifts might no longer stand him in stead there, he removed in desperation to Venice, the receptacle of every kind of trash, thinking to find there new means of carrying on his wicked practices. There, as if conscience-stricken for the evil deeds done by him in the past, feigning himself overcome with the utmost humility and waxing devouter than any man alive, he went and turned Minor Friar and styled himself Fra Alberta da Imola; in which habit he proceeded to lead, to all appearance, a very austere life, greatly commending abstinence and mortification and never eating flesh nor drinking wine, whenas he had not thereof that which was to his liking. In short, scarce was any ware of him when from a thief, a pimp, a forger, a manslayer, he suddenly became a great preacher, without having for all that forsworn the vices aforesaid, whenas he might secretly put them in practice. Moreover, becoming a priest, he would still, whenas he celebrated mass at the altar, an he were seen of many, beweep our Saviour’s passion, as one whom tears cost little, whenas he willed it. Brief, what with his preachings and his tears, he contrived on such wise to inveigle the Venetians that he was trustee and depository of well nigh every will made in the town and guardian of folk’s monies, besides being confessor and counsellor of the most part of the men and women of the place; and doing thus, from wolf he was become shepherd and the fame of his sanctity was far greater in those parts than ever was that of St. Francis at Assisi.

It chanced one day that a vain simple young lady, by name Madam Lisetta da Ca Quirino, wife of a great merchant who was gone with the galleys into Flanders, came with other ladies to confess to this same holy friar, at whose feet kneeling and having, like a true daughter of Venice as she was (where the women are all feather-brained), told him part of her affairs, she was asked of him if she had a lover. Whereto she answered, with an offended air, ‘Good lack, sir friar, have you no eyes in your head? Seem my charms to you such as those of yonder others? I might have lovers and to spare, an I would; but my beauties are not for this one nor that. How many women do you see whose charms are such as mine, who would be fair in Paradise?’ Brief, she said so many things of this beauty of hers that it was a weariness to hear. Fra Alberto incontinent perceived that she savoured of folly and himseeming she was a fit soil for his tools, he fell suddenly and beyond measure in love with her; but, reserving blandishments for a more convenient season, he proceeded, for the nonce, so he might show himself a holy man, to rebuke her and tell her that this was vainglory and so forth. The lady told him he was an ass and knew not what one beauty was more than another, whereupon he, unwilling to vex her overmuch, took her confession and let her go away with the others.

Author: Unknown

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: Public Domain

He let some days pass, then, taking with him a trusty companion of his, he repaired to Madam Lisetta’s house and withdrawing with her into a room apart, where none might see him, he fell on his knees before her and said, ‘Madam, I pray you for God’s sake pardon me that which I said to you last Sunday, whenas you bespoke me of your beauty, for that the following night I was so cruelly chastised there that I have not since been able to rise from my bed till to-day.’ Quoth Mistress Featherbrain, ‘And who chastised you thus?’ ‘I will tell you,’ replied the monk. ‘Being that night at my orisons, as I still use to be, I saw of a sudden a great light in my cell and ere I could turn me to see what it might be, I beheld over against me a very fair youth with a stout cudgel in his hand, who took me by the gown and dragging me to my feet, gave me such a drubbing that he broke every bone in my body. I asked him why he used me thus and he answered, “For that thou presumedst to-day, to disparage the celestial charms of Madam Lisetta, whom I love over all things, save only God.” “Who, then, are you?” asked I; and he replied that he was the angel Gabriel. “O my lord,” said I, “I pray you pardon me”; and he, “So be it; I pardon thee on condition that thou go to her, as first thou mayst, and get her pardon; but if she pardons thee not, I will return to thee and give thee such a bout of it that I will make thee a woeful man for all the time thou shalt live here below.” That which he said to me after I dare not tell you, except you first pardon me.’

My Lady Addlepate, who was somewhat scant of wit, was overjoyed to hear this, taking it all for gospel, and said, after a little, ‘I told you, Fra Alberto, that my charms were celestial, but, so God be mine aid, it irketh me for you and I will pardon you forthright, so you may come to no more harm, provided you tell me truly that which the angel said to you after.’ ‘Madam,’ replied Fra Alberto, ‘since you pardon me, I will gladly tell it you; but I must warn you of one thing, to wit, that whatever I tell you, you must have a care not to repeat it to any one alive, an you would not mar your affairs, for that you are the luckiest lady in the world. The angel Gabriel bade me tell you that you pleased him so much that he had many a time come to pass the night with you, but that he feared to affright you. Now he sendeth to tell you by me that he hath a mind to come to you one night and abide awhile with you and (for that he is an angel and that, if he came in angel-form, you might not avail to touch him,) he purposeth, for your delectation, to come in guise of a man, wherefore he biddeth you send to tell him when you would have him come and in whose form, and he will come hither; whereof you may hold yourself blest over any other lady alive.’

My Lady Conceit answered that it liked her well that the angel Gabriel loved her, seeing she loved him well nor ever failed to light a candle of a groat before him, whereas she saw him depictured, and that what time soever he chose to come to her, he should be dearly welcome and would find her all alone in her chamber, but on this condition, that he should not leave her for the Virgin Mary, whose great well-wisher it was said he was, as indeed appeareth, inasmuch as in every place where she saw him [limned], he was on his knees before her. Moreover, she said it must rest with him to come in whatsoever form he pleased, so but she was not affrighted.

Then said Fra Alberto, ‘Madam, you speak sagely and I will without fail take order with him of that which you tell me. But you may do me a great favour, which will cost you nothing; it is this, that you will him come with this my body. And I will tell you in what you will do me a favour; you must know that he will take my soul forth of my body and put it in Paradise, whilst he himself will enter into me; and what while he abideth with you, so long will my soul abide in Paradise.’ ‘With all my heart,’ answered Dame Littlewit. ‘I will well that you have this consolation, in requital of the buffets he gave you on my account.’ Then said Fra Alberto, ‘Look that he find the door of your house open to-night, so he may come in thereat, for that, coming in human form, as he will, he might not enter save by the door.’ The lady replied that it should be done, whereupon the monk took his leave and she abode in such a transport of exultation that her breech touched not her shift and herseemed a thousand years till the angel Gabriel should come to her.

Meanwhile, Fra Alberto, bethinking him that it behoved him play the cavalier, not the angel, that night proceeded to fortify himself with confections and other good things, so he might not lightly be unhorsed; then, getting leave, as soon as it was night, he repaired with one of his comrades to the house of a woman, a friend of his, whence he was used whiles to take his start what time he went to course the fillies; and thence, whenas it seemed to him time, having disguised himself, he betook him to the lady’s house. There he tricked himself out as an angel with the trappings he had brought with him and going up, entered the chamber of the lady, who, seeing this creature all in white, fell on her knees before him. The angel blessed her and raising her to her feet, signed to her to go to bed, which she, studious to obey, promptly did, and the angel after lay down with his devotee. Now Fra Alberto was a personable man of his body and a lusty and excellent well set up on his legs; wherefore, finding himself in bed with Madam Lisetta, who was young and dainty, he showed himself another guess bedfellow than her husband and many a time that night took flight without wings, whereof she avowed herself exceeding content; and eke he told her many things of the glories of heaven. Then, the day drawing near, after taking order for his return, he made off with his trappings and returned to his comrade, whom the good woman of the house had meanwhile borne amicable company, lest he should get a fright, lying alone.

As for the lady, no sooner had she dined than, taking her waiting-woman with her, she betook herself to Fra Alberto and gave him news of the angel Gabriel, telling him that which she had heard from him of the glories of life eternal and how he was made and adding to boot, marvellous stories of her own invention. ‘Madam,’ said he, ‘I know not how you fared with him; I only know that yesternight, whenas he came to me and I did your message to him, he suddenly transported my soul amongst such a multitude of roses and other flowers that never was the like thereof seen here below, and I abode in one of the most delightsome places that was aye until the morning; but what became of my body meanwhile I know not.’ ‘Do I not tell you?’ answered the lady. ‘Your body lay all night in mine arms with the angel Gabriel. If you believe me not, look under your left pap, whereas I gave the angel such a kiss that the marks of it will stay by you for some days to come.’ Quoth the friar, ‘Say you so? Then will I do to-day a thing I have not done this great while; I will strip myself, to see if you tell truth.’ Then, after much prating, the lady returned home and Fra Alberto paid her many visits in angel-form, without suffering any hindrance.

However, it chanced one day that Madam Lisetta, being in dispute with a gossip of hers upon the question of female charms, to set her own above all others, said, like a woman who had little wit in her noddle, ‘An you but knew whom my beauty pleaseth, in truth you would hold your peace of other women.’ The other, longing to hear, said, as one who knew her well, ‘Madam, maybe you say sooth; but knowing not who this may be, one cannot turn about so lightly.’ Thereupon quoth Lisetta, who was eath enough to draw, ‘Gossip, it must go no farther; but he I mean is the angel Gabriel, who loveth me more than himself, as the fairest lady (for that which he telleth me) who is in the world or the Maremma.’ The other had a mind to laugh, but contained herself, so she might make Lisetta speak farther, and said, ‘Faith, madam, an the angel Gabriel be your lover and tell you this, needs must it be so; but methought not the angels did these things.’ ‘Gossip,’ answered the lady, ‘you are mistaken; zounds, he doth what you wot of better than my husband and telleth me they do it also up yonder; but, for that I seem to him fairer than any she in heaven, he hath fallen in love with me and cometh full oft to lie with me; seestow now?’

The gossip, to whom it seemed a thousand years till she should be whereas she might repeat these things, took her leave of Madam Lisetta and foregathering at an entertainment with a great company of ladies, orderly recounted to them the whole story. They told it again to their husbands and other ladies, and these to yet others, and so in less than two days Venice was all full of it. Among others to whose ears the thing came were Lisetta’s brothers-in-law, who, without saying aught to her, bethought themselves to find the angel in question and see if he knew how to fly, and to this end they lay several nights in wait for him. As chance would have it, some inkling of the matter came to the ears of Fra Alberto, who accordingly repaired one night to the lady’s house, to reprove her, but hardly had he put off his clothes ere her brothers-in-law, who had seen him come, were at the door of her chamber to open it.

Fra Alberto, hearing this and guessing what was to do, started up and having no other resource, opened a window, which gave upon the Grand Canal, and cast himself thence into the water. The canal was deep there and he could swim well, so that he did himself no hurt, but made his way to the opposite bank and hastily entering a house that stood open there, besought a poor man, whom he found within, to save his life for the love of God, telling him a tale of his own fashion, to explain how he came there at that hour and naked. The good man was moved to pity and it behoving him to go do his occasions, he put him in his own bed and bade him abide there against his return; then, locking him in, he went about his affairs. Meanwhile, the lady’s brothers-in-law entered her chamber and found that the angel Gabriel had flown, leaving his wings there; whereupon, seeing themselves baffled, they gave her all manner hard words and ultimately made off to their own house with the angel’s trappings, leaving her disconsolate.

Broad day come, the good man with whom Fra Alberto had taken refuge, being on the Rialto, heard how the angel Gabriel had gone that night to lie with Madam Lisetta and being surprised by her kinsmen, had cast himself for fear into the canal, nor was it known what was come of him, and concluded forthright that this was he whom he had at home. Accordingly, he returned thither and recognizing the monk, found means after much parley, to make him fetch him fifty ducats, an he would not have him give him up to the lady’s kinsmen. Having gotten the money and Fra Alberto offering to depart thence, the good man said to him, ‘There is no way of escape for you, an it be not one that I will tell you. We hold to-day a festival, wherein one bringeth a man clad bear-fashion and another one accoutred as a wild man of the woods and what not else, some one thing and some another, and there is a hunt held in St. Mark’s Place, which finished, the festival is at an end and after each goeth whither it pleaseth him with him whom he hath brought. An you will have me lead you thither, after one or other of these fashions, I can after carry you whither you please, ere it be spied out that you are here; else I know not how you are to get away, without being recognized, for the lady’s kinsmen, concluding that you must be somewhere hereabout, have set a watch for you on all sides.’

Hard as it seemed to Fra Alberto to go on such wise, nevertheless, of the fear he had of the lady’s kinsmen, he resigned himself thereto and told his host whither he would be carried, leaving the manner to him. Accordingly, the other, having smeared him all over with honey and covered him with down, clapped a chain about his neck and a mask on his face; then giving him a great staff in on hand and in the other two great dogs which he had fetched from the shambles he despatched one to the Rialto to make public proclamation that whoso would see the angel Gabriel should repair to St. Mark’s Place; and this was Venetian loyalty! This done, after a while, he brought him forth and setting him before himself, went holding him by the chain behind, to the no small clamour of the folk, who said all, ‘What be this? What be this?’ till he came to the place, where, what with those who had followed after them and those who, hearing the proclamation, were come thither from the Rialto, were folk without end. There he tied his wild man to a column in a raised and high place, making a show of awaiting the hunt, whilst the flies and gads gave the monk exceeding annoy, for that he was besmeared with honey. But, when he saw the place well filled, making as he would unchain his wild man, he pulled off Fra Alberto’s mask and said, ‘Gentlemen, since the bear cometh not and there is no hunt toward, I purpose, so you may not be come in vain, that you shall see the angel Gabriel, who cometh down from heaven to earth anights, to comfort the Venetian ladies.’

No sooner was the mask off than Fra Alberto was incontinent recognized of all, who raised a general outcry against him, giving him the scurviest words and the soundest rating was ever given a canting knave; moreover, they cast in his face, one this kind of filth and another that, and so they baited him a great while, till the news came by chance to his brethren, whereupon half a dozen of them sallied forth and coming thither, unchained him and threw a gown over him; then, with a general hue and cry behind them, they carried him off to the convent, where it is believed he died in prison, after a wretched life. Thus then did this fellow, held good and doing ill, without it being believed, dare to feign himself the angel Gabriel, and after being turned into a wild man of the woods and put to shame, as he deserved, bewailed, when too late, the sins he had committed. God grant it happen thus to all other knaves of his fashion!”

Day the Fifth

The Ninth Story

Federigo degli alberighi loveth and is not loved. He wasteth his substance in prodigal hospitality till there is left him but one sole falcon, which, having nought else, he giveth his mistress to eat, on her coming to his house; and she, learning this, changeth her mind and taking him to husband, maketh him rich again.

Filomena having ceased speaking, the queen, seeing that none remained to tell save only herself and Dioneo, whose privilege entitled him to speak last, said, with blithe aspect, “It pertaineth now to me to tell and I, dearest ladies, will willingly do it, relating a story like in part to the foregoing, to the intent that not only may you know how much the love of you can avail in gentle hearts, but that you may learn to be yourselves, whenas it behoveth, bestowers of your guerdons, without always suffering fortune to be your guide, which most times, as it chanceth, giveth not discreetly, but out of all measure.

You must know, then, that Coppo di Borghese Domenichi, who was of our days and maybe is yet a man of great worship and authority in our city and illustrious and worthy of eternal renown, much more for his fashions and his merit than for the nobility of his blood, being grown full of years, delighted oftentimes to discourse with his neighbours and others of things past, the which he knew how to do better and more orderly and with more memory and elegance of speech than any other man. Amongst other fine things of his, he was used to tell that there was once in Florence a young man called Federigo, son of Messer Filippo Alberighi and renowned for deeds of arms and courtesy over every other bachelor in Tuscany, who, as betideth most gentlemen, became enamoured of a gentlewoman named Madam Giovanna, in her day held one of the fairest and sprightliest ladies that were in Florence; and to win her love, he held jousts and tourneyings and made entertainments and gave gifts and spent his substance without any stint; but she, being no less virtuous than fair, recked nought of these things done for her nor of him who did them. Federigo spending thus far beyond his means and gaining nought, his wealth, as lightly happeneth, in course of time came to an end and he abode poor, nor was aught left him but a poor little farm, on whose returns he lived very meagrely, and to boot a falcon he had, one of the best in the world. Wherefore, being more in love than ever and himseeming he might no longer make such a figure in the city as he would fain do, he took up his abode at Campi, where his farm was, and there bore his poverty with patience, hawking whenas he might and asking of no one.

Federigo being thus come to extremity, it befell one day that Madam Giovanna’s husband fell sick and seeing himself nigh upon death, made his will, wherein, being very rich, he left a son of his, now well grown, his heir, after which, having much loved Madam Giovanna, he substituted her to his heir, in case his son should die without lawful issue, and died. Madam Giovanna, being thus left a widow, betook herself that summer, as is the usance of our ladies, into the country with her son to an estate of hers very near that of Federigo; wherefore it befell that the lad made acquaintance with the latter and began to take delight in hawks and hounds, and having many a time seen his falcon flown and being strangely taken therewith, longed sore to have it, but dared not ask it of him, seeing it so dear to him. The thing standing thus, it came to pass that the lad fell sick, whereat his mother was sore concerned, as one who had none but him and loved him with all her might, and abode about him all day, comforting him without cease; and many a time she asked him if there were aught he desired, beseeching him tell it her, for an it might be gotten, she would contrive that he should have it. The lad, having heard these offers many times repeated, said, ‘Mother mine, an you could procure me to have Federigo’s falcon, methinketh I should soon be whole.’

The lady hearing this, bethought herself awhile and began to consider how she should do. She knew that Federigo had long loved her and had never gotten of her so much as a glance of the eye; wherefore quoth she in herself, ‘How shall I send or go to him to seek of him this falcon, which is, by all I hear, the best that ever flew and which, to boot, maintaineth him in the world? And how can I be so graceless as to offer to take this from a gentleman who hath none other pleasure left?’ Perplexed with this thought and knowing not what to say, for all she was very certain of getting the bird, if she asked for it, she made no reply to her son, but abode silent. However, at last, the love of her son so got the better of her that she resolved in herself to satisfy him, come what might, and not to send, but to go herself for the falcon and fetch it to him. Accordingly she said to him, ‘My son, take comfort and bethink thyself to grow well again, for I promise thee that the first thing I do to-morrow morning I will go for it and fetch it to thee.’ The boy was rejoiced at this and showed some amendment that same day.

Next morning, the lady, taking another lady to bear her company, repaired, by way of diversion, to Federigo’s little house and enquired for the latter, who, for that it was no weather for hawking nor had been for some days past, was then in a garden he had, overlooking the doing of certain little matters of his, and hearing that Madam Giovanna asked for him at the door, ran thither, rejoicing and marvelling exceedingly. She, seeing him come, rose and going with womanly graciousness to meet him, answered his respectful salutation with ‘Give you good day, Federigo!’ then went on to say, ‘I am come to make thee amends for that which thou hast suffered through me, in loving me more than should have behooved thee; and the amends in question is this that I purpose to dine with thee this morning familiarly, I and this lady my companion.’ ‘Madam,’ answered Federigo humbly, ‘I remember me not to have ever received any ill at your hands, but on the contrary so much good that, if ever I was worth aught, it came about through your worth and the love I bore you; and assuredly, albeit you have come to a poor host, this your gracious visit is far more precious to me than it would be an it were given me to spend over again as much as that which I have spent aforetime.’ So saying, he shamefastly received her into his house and thence brought her into his garden, where, having none else to bear her company, he said to her, ‘Madam, since there is none else here, this good woman, wife of yonder husbandman, will bear you company, whilst I go see the table laid.’

Never till that moment, extreme as was his poverty, had he been so dolorously sensible of the straits to which he had brought himself for the lack of those riches he had spent on such disorderly wise. But that morning, finding he had nothing wherewithal he might honourably entertain the lady, for love of whom he had aforetime entertained folk without number, he was made perforce aware of his default and ran hither and thither, perplexed beyond measure, like a man beside himself, inwardly cursing his ill fortune, but found neither money nor aught he might pawn. It was now growing late and he having a great desire to entertain the gentle lady with somewhat, yet choosing not to have recourse to his own labourer, much less any one else, his eye fell on his good falcon, which he saw on his perch in his little saloon; whereupon, having no other resource, he took the bird and finding him fat, deemed him a dish worthy of such a lady. Accordingly, without more ado, he wrung the hawk’s neck and hastily caused a little maid of his pluck it and truss it and after put it on the spit and roast it diligently. Then, the table laid and covered with very white cloths, whereof he had yet some store, he returned with a blithe countenance to the lady in the garden and told her that dinner was ready, such as it was in his power to provide. Accordingly, the lady and her friend, arising, betook themselves to table and in company with Federigo, who served them with the utmost diligence, ate the good falcon, unknowing what they did.