Realism

The dates for Realism as a movement vary, from as early as 1820 to as late as 1920. Although Realism is, in many ways, a rejection of Romanticism, it does address some of the same concerns about the industrial revolution that Wordsworth had expressed earlier. The passage of years increased the number of authors who noted the failures of industrialization, especially where pollution and quality of life were concerned. The British period of Victorianism (1837-1901) saw a gradual shifting from Romanticism to Realism. Poets such as Tennyson and Robert Browning are more properly transitional poets: products of Romanticism, but who express themselves in more realistic terms. It is important to remember not only that literary movements are not set in stone, but also that they are not always identified the same way by their own time period. When Charles Baudelaire wrote his seminal work, The Flowers of Evil (1857), he was praised as a poet of Romanticism by Gustave Flaubert, even though most modern scholars locate Baudelaire in Realism, and later poets of Modernism cite him as an early example of their own movement.

Romanticism was slowly but surely replaced with an attempt to see the world as it is. As later generations would note, it is difficult to represent reality in its entirety in one poem, play, short story, or novel. Early Realists tended to include more portrayals of middle class and/or lower class characters, who previously were not the main subjects of literature. In Europe, writers such as Ibsen wrote about the middle class specifically, using ordinary occurrences (at least, ordinary for the middle class experience) as the stuff of drama. Authors such as Henry James occasionally were criticized for novels in which very little seems to happen, since ordinary events are rarely as dramatic as the situations regularly found in Romanticism. In some cases, the attempt to be more realistic led to many works that focused on the negative aspects of humans, leaving out the positive aspects to avoid Romantic overtones.

Instead of Romanticism’s belief in the power of emotion and intuition to achieve insight, Realism addressed more concrete issues, usually with direct and straightforward language. In American Realism, Mark Twain’s use of dialect falls into this category. Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) is realistic in its use of common, everyday speech, which includes dialect and slang. The novel also offers a realistic portrayal of the complicated friendship that slowly develops between Huck, a poor white boy, and Jim, a runaway slave.

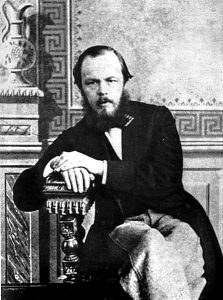

Another way that Realism distinguished itself from the previous movement was in its examination of human psychology. Robert Browning looked at the psychology of narcissists, murderers, and psychopaths in many of his dramatic monologues. Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novels take place as much in the minds of the characters as they do in the interactions among characters. In Notes from Underground (1864), Dostoyevsky uses Realism to explore the allure (and dangers) of Romanticism, including its continuing hold on audiences. Dostoyevsky’s “Underground Man” attempts to explain not only why he does what he does, but claims that the reader is no different—a tactic used by Baudelaire in his poem “To The Reader” at the beginning of The Flowers of Evil.

As a general guideline, Realism tended to point out society’s problems (and the problems with the Romantic view), but offered observations, rather than suggested changes. Naturalism, a subset of Realism often treated as a separate movement, was regularly motivated by a desire to improve the world. Naturalism concerned itself with the poorest members of society in particular, and social change was the goal. Naturalism was criticized for being even more focused on the negative aspects of life than regular Realism. Emile Zola’s novel Germinal (1885) is perhaps the most famous example of Naturalism. In it, Zola depicts the lead-up to and aftermath of a coal miners’ strike with a stark realism that shocked readers. His unsentimental portrayal (in almost journalistic fashion) of events angered both conservatives (reluctant to admit the brutal working and living conditions of the poor) and socialists (unhappy that the workers were not Romantic heroes). Eventually, Modernism began in literature as Realism and Naturalism were ending, overlapping for a brief period of time. Perhaps not surprisingly, Modernism would claim to be more real than Realism—or, as the artist Georgia O’Keeffe said, “Nothing is less real than realism” (Haber), preferring abstract art as a way to arrive at a more complete image of (one type of) truth.

Written by Laura Getty