Middle East, Near East, Greece

The texts chosen for this chapter were influential in their own times and beyond. Gilgamesh was an ancient Sumerian king whose story was valued and retold by other cultures who invaded the area. The Bible remains one of the most widely read books in history. Homer’s epics form a cornerstone of western literature, and the two plays selected from ancient Greek drama influenced countless writers after them. Only the plays were originally written works; the other texts were part of an oral tradition before they were written down. Even then, the subject matter of the plays is not original to the authors: The audience knew the stories of Oedipus and Medea already. Homer was not the first (or the last) to compose poems on the Trojan War and its aftermath. Originality was not particularly prized in an oral culture, where only the best works were worth memorizing. Homer’s fame comes from how well he tells his version of events.

When reading the selected texts, remember that the contemporary definition of a hero or leader is often not compatible with the ancient world’s definition of a hero or leader. Each society, and sometimes each time period in each society, can have a different definition, based on what the expectations were. There is also a difference between the modern idea of an action hero and the ancient world’s definition of an epic hero. To be the hero of an epic, the character needs to meet at least some of the following requirements: He receives divine intervention (or is chosen by the gods to win), has superhuman strength or abilities, is of national or international importance, has the ability to overcome and learn from a personal flaw, and goes on a significant journey. The ultimate goal of epic heroes is to be remembered: achieving immortality through their deeds, which will live on in stories. Unlike a modern film hero who might be expected to act in the best interests of others, epic heroes may or may not act with other people’s interests in mind. Some of the epic heroes in this chapter fight to protect others, but many fight for personal glory, regardless of the collateral damage. In other words, an epic hero is an ideal warrior in his society, but not always an ideal human being. In the Iliad, Achilles is the greatest warrior among the Greeks, and his main concern is making a name for himself that will last forever. When he is insulted by Agamemnon, therefore, he asks that Zeus punish Achilles’ own side, slaughtering the Greeks until they beg him for forgiveness. Achilles fights for his own glory, not the glory of others.

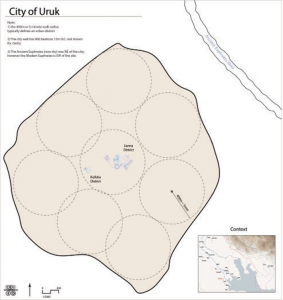

In Gilgamesh, the title character begins the story as an impressive epic hero, but a poor leader (as the gods themselves indicate in the story when they respond to the prayers of the citizens of Uruk, who are begging the gods to protect them from their own king). Gilgamesh’s lack of morality stems in part from his demigod status; as the ancient Sumerians recognized, their pantheon of gods was not particularly moral. Since epic heroes need the help of the gods to win, the focus is not on individual strength, but on gaining the favor of the gods. Yes, Gilgamesh is strong, but to fight the supernatural creature Humbaba, Gilgamesh needs help: his mother’s prayers to the gods, his friend Enkidu’s support, supernatural weapons from the god Shamash (namely the winds), and his tears as offerings to Shamash in exchange for his help. The expectations for a good king are clear in the text, but they conflict on some level with the expectations for an epic hero in this case.

License: Open Government License (OGL)

The hero who receives divine intervention is the one who wins every time, so being humble to the gods is vital for success. When Brad Pitt plays Achilles in the movie Troy, there are no toddler tantrums; in the Iliad, Achilles cries every time he wants the help of his mother, the goddess Thetis. The modern film expectations for the character of Achilles would be foreign (and strange, and irreligious) to the original audience, just as a modern American film audience would not be impressed by an action hero who sobbed to his mother for help. The original audience, however, would be familiar with example after example of how pointless it is to try to win without the help of the gods: No matter who would have won based on his own strength, the gods determine the final result. Human strength means little in such a universe.

Source: Wikimedia Commons License: CC BY-SA 2.5

Equally pointless is the attempt to change fate, which is the one force in the Greek stories that is stronger than the gods. Zeus cannot change the outcome of various events in the Iliad, and Oedipus realizes the futility of attempting to change his fate. The fatalistic approach of the Greek texts stems from the belief that the ages of man are in a decline, from the golden age down to the iron age of Homer. This belief in the general decline of humanity is echoed later in Dante’s Inferno, where the Old Man of Crete is composed of the same metals, but this time with a clay foot.

As you read, consider the following questions:

- Using the list of traits above, which traits apply to each epic hero in the texts?

- What is similar and/or different about heroes such as Gilgamesh, Achilles, Hector, and Odysseus?

- How do the characters view the gods, and how do the gods treat humans?

- What do we learn about what each society considers proper or improper behavior, again based on the text itself?