Noh Plays

Zeami Motokiyo

(1363-1443 C.E.)

Appeared distinctively in the fourteenth century Japan

Noh (also spelled Nō, meaning “talent” or “skill”) theatre is a traditional Japanese theatrical form that came to have a distinctive form in the fourteenth century and continued to develop up to the Tokugawa period (1603-1867). Noh theatre, one of the oldest extant theatre forms in the world, has been handed down from generation to generation, keeping its early forms fairly intact. Unlike performers of Kabuki (another traditional Japanese theatrical form) who use elaborate makeup, Noh performers wear masks. Compared to typical western theatre, a Noh play is relatively short without a lot of action; instead, Noh performers emphasize sounds and movements as visual metaphors suggesting the story on stage. Traditionally, they were performed mainly for the warrior class, whereas currently this theatre is protected and supported at the national level. Zeami Motokiyo, along with his father, wrote many of the most exemplary Noh plays. Zeami also formulated the principles of the Noh theatre. There are five types of Noh plays: the plays about 1) gods, 2) warriors, 3) a female protagonist, 4) a madwoman in a contemporary setting, and 5) devils, monsters, and supernatural beings. Zeami’s play “Atsumori,” for example, belongs to the plays about warriors. It dramatizes a wellknown episode from The Tale of the Heike (ca. 1240 C.E.), a famous, medieval Japanese epic.

Written by Kyounghye Kwon

The Nō Plays of Japan

Arthur Waley

License: Public Domain

Introduction

The theatre of the West is the last stronghold of realism. No one treats painting or music as mere transcripts of life. But even pioneers of stage-reform in France and Germany appear to regard the theatre as belonging to life and not to art. The play is an organized piece of human experience which the audience must as far as possible be allowed to share with the actors.

A few people in America and Europe want to go in the opposite direction. They would like to see a theatre that aimed boldly at stylization and simplification, discarding entirely the pretentious lumber of 19th century stageland. That such a theatre exists and has long existed in Japan has been well-known here for some time. But hitherto very few plays have been translated in such a way as to give the Western reader an idea of their literary value. It is only through accurate scholarship that the “soul of Nō” can be known to the West. Given a truthful rendering of the texts the American reader will supply for himself their numerous connotations, a fact which Japanese writers do not always sufficiently realize. The Japanese method of expanding a five-line poem into a long treatise in order to make it intelligible to us is one which obliterates the structure of the original design. Where explanations are necessary they have been given in footnotes. I have not thought it necessary to point out (as a Japanese critic suggested that I ought to have done) that, for example, the “mood” of Komachi is different from the “mood” of Kumasaka. Such differences will be fully apparent to the American reader, who would not be the better off for knowing the technical name of each kurai or class of Nō. Surely the Japanese student of Shakespeare does not need to be told that the kurai of “Hamlet” is different from that of “Measure for Measure”?

It would be possible to burden a book of this kind with as great a mass of unnecessary technicality as irritates us in a smart sale-catalogue of Japanese Prints. I have avoided such terms to a considerable extent, treating the plays as literature, not as some kind of Delphic mystery.

In this short introduction I shall not have space to give a complete description of modern Nō, nor a full history of its origins. But the reader of the translations will find that he needs some information on these points. I have tried to supply it as concisely as possible, sometimes in a schematic rather than a literary form.

These are some of the points about which an American reader may wish to know more:

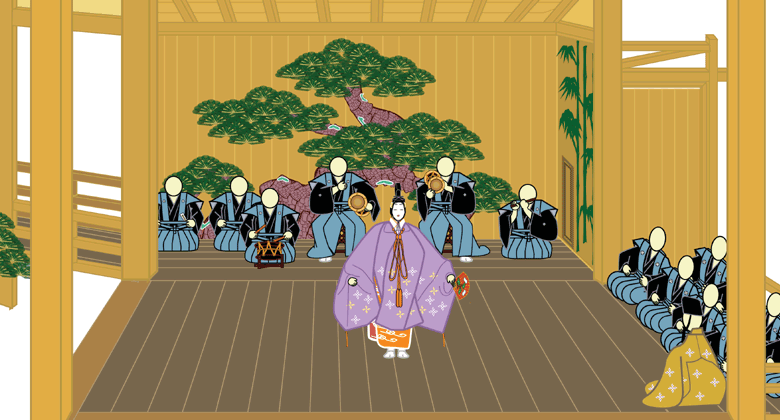

The Nō Stage

The actual stage is about 18 feet square. On the boards of the back wall is painted a pine-tree; the other sides are open. A gallery (called hashigakari) leads to the green-room, from which it is separated by a curtain which is raised to admit the actor when he makes his entry. The audience sits either on two or three sides of the stage. The chorus, generally in two rows, sit (or rather squat) in the recess. The musicians sit in the recess at the back of the stage, the stick-drum nearest the “gallery,” then the two hand-drums and the flute. A railing runs round the musician’s recess, as also along the gallery. To the latter railing are attached three real pine-branches. The stage is covered by a roof of its own, imitating in form the roof of a Shintō temple.

The Performers

The Actors

The first actor who comes on to the stage (approaching from the gallery) is the waki or assistant. His primary business is to explain the circumstances under which the principal actor (called shite or “doer”) came to dance the central dance of the play. Each of these main actors (waki and shite) has “adjuncts” or “companions.”

Some plays need only the two main actors. Others use as many as ten or even twelve. The female rôles are of course taken by men. The waki is always a male rôle.

The Chorus

This consists of from eight to twelve persons in ordinary native dress seated in two rows at the side of the stage. Their sole function is to sing an actor’s words for him when his dance-movements prevent him from singing comfortably. They enter by a side-door before the play begins and remain seated till it is over.

The Musicians

Nearest to the gallery sits the “big-drum,” whose instrument rests on the ground and is played with a stick. This stickdrum is not used in all plays. Next comes a hand-drummer who plays with thimbled finger; next a second who plays with the bare hand. Finally, the flute. It intervenes only at stated intervals, particularly at the beginning, climax and end of plays.

Costume

Though almost wholly banishing other extrinsic aids, the Nō relies enormously for its effects on gorgeous and elaborate costume. Some references to this will be found in Oswald Sickert’s letters at the end of my book. Masks are worn only by the shite (principal actor) and his subordinates. The shite always wears a mask if playing the part of a woman or very old man. Young men, particularly warriors, are usually unmasked. In child-parts (played by boy-actors) masks are not worn. The reproduction of a female mask will be found on Plate I. The masks are of wood. Many of those still in use are of great antiquity and rank as important specimens of Japanese sculpture.

Properties

The properties of the Nō stage are of a highly conventionalized kind. An open frame-work represents a boat; another differing little from it denotes a chariot. Palace, house, cottage, hovel are all represented by four posts covered with a roof. The fan which the actor usually carries often does duty as a knife, brush or the like. Weapons are more realistically represented. The short-sword, belt-sword, pike, spear and Chinese broad-sword are carried; also bows and arrows.

Dancing and Acting

Every Nō play (with, I think, the sole exception of Hachi no Ki) includes a mai or dance, consisting usually of slow steps and solemn gestures, often bearing little resemblance to what is in America associated with the word “dance.” When the shite dances, his dance consists of five “movements” or parts; a “subordinate’s” dance consists of three. Both in the actors’ miming and in the dancing an important element is the stamping of beats with the shoeless foot.

The Plays

The plays are written partly in prose, partly in verse. The prose portions serve much the same purpose as the iambics in a Greek play. They are in the Court or upper-class colloquial of the 14th century, a language not wholly dead to-day, as it is still the language in which people write formal letters.

The chanting of these portions is far removed from singing; yet they are not “spoken.” The voice falls at the end of each sentence in a monotonous cadence.

A prose passage often gradually heightens into verse. The chanting, which has hitherto resembled the intoning of a Roman Catholic priest, takes on more of the character of “recitativo” in opera, occasionally attaining to actual song. The verse of these portions is sometimes irregular, but on the whole tends to an alternation of lines of five and seven syllables.

The verse of the lyric portions is marked by frequent use of pivot-words and puns, particularly puns on placenames. The 14th century Nō-writer, Seami, insists that pivot-words should be used sparingly and with discretion. Many Nō-writers did not follow this advice; but the use of pivot-words is not in itself a decoration more artificial than rhyme, and I cannot agree with those European writers to whom this device appears puerile and degraded. Each language must use such embellishments as suit its genius.

Another characteristic of the texts is the use of earlier literary material. Many of the plays were adapted from dance-ballads already existing and even new plays made use of such poems as were associated in the minds of the audience with the places or persons named in the play. Often a play is written round a poem or series of poems, as will be seen in the course of this book.

This use of existing material exceeds the practice of Western dramatists; but it must be remembered that if we were to read Webster, for example, in editions annotated as minutely as the Nō-plays, we should discover that he was far more addicted to borrowing than we had been aware. It seems to me that in the finest plays this use of existing material is made with magnificent effect and fully justifies itself.

The reference which I have just made to dance-ballads brings us to another question. What did the Nō-plays grow out of?

Origins

Nō as we have it to-day dates from about the middle of the 14th century. It was a combination of many elements.

These were:

Sarugaku, a masquerade which relieved the solemnity of Shintō ceremonies. What we call Nō was at first called Sarugaku no Nō.

Dengaku, at first a rustic exhibition of acrobatics and jugglery; later, a kind of opera in which performers alternately danced and recited.

Various sorts of recitation, ballad-singing, etc.

The Chinese dances practised at the Japanese Court.

Nō owes its present form to the genius of two men. Kwanami Kiyotsugu (1333-1384 A. D.) and his son Seami Motokiyo (1363-1444 A. D.)

Kwanami was a priest of the Kasuga Temple near Nara. About 1375 the Shōgun Yoshimitsu saw him performing in a Sarugaku no Nō at the New Temple (one of the three great temples of Kumano) and immediately took him under his protection.

This Yoshimitsu had become ruler of Japan in 1367 at the age of ten. His family had seized the Shōgunate in 1338 and wielded absolute power at Kyōto, while two rival Mikados, one in the north and one in the south, held impotent and dwindling courts.

The young Shōgun distinguished himself by patronage of art and letters; and by his devotion to the religion of the Zen Sect. It is probable that when he first saw Kwanami he also became acquainted with the son Seami, then a boy of twelve.

A diary of the period has the following entry for the 7th day of the 6th month, 1368:

For some while Yoshimitsu has been making a favourite of a Sarugaku-boy from Yamato, sharing the same meat and eating from the same vessels. These Sarugaku people are mere mendicants, but he treats them as if they were Privy Counsellors.

From this friendship sprang the art of Nō as it exists to-day. Of Seami we know far more than of his father Kwanami. For Seami left behind him a considerable number of treatises and autobiographical fragments. These were not published till 1908 and have not yet been properly edited. They establish, among other things, the fact that Seami wrote both words and music for most of the plays in which he performed. It had before been supposed that the texts were supplied by the Zen priests. For other information brought to light by the discovery of Seami’s Works see Appendix II.

Yūgen

It is obvious that Seami was deeply imbued with the teachings of Zen, in which cult his patron Yoshimitsu may have been his master. The difficult term yūgen which occurs constantly in the Works is derived from Zen literature. It means “what lies beneath the surface”; the subtle as opposed to the obvious; the hint, as opposed to the statement. It is applied to the natural grace of a boy’s movements, to the restraint of a nobleman’s speech and bearing. “When notes fall sweetly and flutter delicately to the ear,” that is the yūgen of music. The symbol of yūgen is “a white bird with a flower in its beak.” “To watch the sun sink behind a flower-clad hill, to wander on and on in a huge forest with no thought of return, to stand upon the shore and gaze after a boat that goes hid by far-off islands, to ponder on the journey of wild-geese seen and lost among the clouds”—such are the gates to yūgen.

I will give a few specimens of Seami’s advice to his pupils:

Patrons

The actor should not stare straight into the faces of the audience, but look between them. When he looks in the direction of the Daimyōs he must not let his eyes meet theirs, but must slightly avert his gaze.

At Palace-performances or when acting at a banquet, he must not let his eyes meet those of the Shōgun or stare straight into the Honourable Face. When playing in a large enclosure he must take care to keep as close as possible to the side where the Nobles are sitting; if in a small enclosure, as far off as possible. But particularly in Palace-performances and the like he must take the greatest pains to keep as far away as he possibly can from the August Presence.

Again, when the recitations are given at the Palace it is equally essential to begin at the right moment. It is bad to begin too soon and fatal to delay too long.

It sometimes happens that the “noble gentlemen” do not arrive at the theatre until the play has already reached its Development and Climax. In such cases the play is at its climax, but the noble gentlemen’s hearts are ripe only for Introduction. If they, ready only for Introduction, are forced to witness a Climax, they are not likely to get pleasure from it. Finally even the spectators who were there before, awed by the entry of the “exalted ones,” become so quiet that you would not know they were there, so that the whole audience ends by returning to the Introductory mood. At such a moment the Nō cannot possibly be a success. In such circumstances it is best to take Development-Nō and give it a slightly “introductory” turn. Then, if it is played gently, it may win the August Attention.

It also happens that one is suddenly sent for to perform at a Shōgunal feast or the like. The audience is already in a “climax-mood”; but “introductory” Nō must be played. This is a great difficulty. In such circumstances the best plan is to tinge the introduction with a nuance of “development.” But this must be done without “stickiness,” with the lightest possible touch, and the transition to the real Development and Climax must be made as quickly as possible.

In old times there were masters who perfected themselves in Nō without study. But nowadays the nobles and gentlemen have become so critical that they will only look with approbation on what is good and will not give attention to anything bad.

Their honourable eyes have become so keen that they notice the least defect, so that even a masterpiece that is as pearls many times polished or flowers choicely culled will not win the applause of our gentlemen to-day.

At the same time, good actors are becoming few and the Art is gradually sinking towards its decline. For this reason, if very strenuous study is not made, it is bound to disappear altogether.

When summoned to play before the noble gentlemen, we are expected to give the regular “words of good-wish” and to divide our performance into the three parts, Introduction, Development and Climax, so that the pre-arranged order cannot be varied . . . But on less formal occasions, when, for example, one is playing not at a Shōgunal banquet but on a common, everyday (yo no tsune) stage, it is obviously unnecessary to limit oneself to the set forms of “happy wish.”

One’s style should be easy and full of graceful yūgen, and the piece selected should be suitable to the audience. A ballad (ko-utai) or dance-song (kuse-mai) of the day will be best. One should have in one’s repertory a stock of such pieces and be ready to vary them according to the character of one’s audience.

In the words and gestures (of a farce, kyōgen) there should be nothing low. The jokes and repartee should be such as suit the august ears of the nobles and gentry. On no account must vulgar words or gestures be introduced, however funny they may be. This advice must be carefully observed.

Introduction, Development and Climax must also be strictly adhered to when dancing at the Palace. If the chanting proceeds from an “introductory-mood,” the dancing must belong to the same moodWhen one is suddenly summoned to perform at a riotous banquet, one must take into consideration the state of the noble gentlemen’s spirits.

Imitation (Monomane)

In imitation there should be a tinge of the “unlike.” For if imitation be pressed too far it impinges on reality and ceases to give an impression of likeness. If one aims only at the beautiful, the “flower” is sure to appear. For example, in acting the part of an old man, the master actor tries to reproduce in his dance only the refinement and venerability of an old gentleman. If the actor is old himself, he need not think about producing an impression of old age….

The appearance of old age will often be best given by making all movements a little late, so that they come just after the musical beat. If the actor bears this in mind, he may be as lively and energetic as he pleases. For in old age the limbs are heavy and the ears slow; there is the will to move but not the corresponding capacity.

It is in such methods as this that true imitation lies.Youthful movements made by an old person are, indeed, delightful; they are like flowers blossoming on an old tree.

If, because the actor has noticed that old men walk with bent knees and back and have shrunken frames, he simply imitates these characteristics, he may achieve an appearance of decrepitude, but it will be at the expense of the “flower.” And if the “flower” be lacking there will be no beauty in his impersonation.

Women should be impersonated by a young actorIt is very difficult to play the part of a Princess or lady-in-waiting, for little opportunity presents itself of studying their august behaviour and appearance. Great pains must be taken to see that robes and cloaks are worn in the correct way. These things do not depend on the actor’s fancy but must be carefully ascertained.

The appearance of ordinary ladies such as one is used to see about one is easy to imitateIn acting the part of a dancing-girl, mad-woman or the like, whether he carry the fan or some fancy thing (a flowering branch, for instance) the actor must carry it loosely; his skirts must trail low so as to hide his feet; his knees and back must not be bent, his body must be poised gracefully. As regards the way he holds himself—if he bends back, it looks bad when he faces the audience; if he stoops, it looks bad from behind. But he will not look like a woman if he holds his head too stiffly. His sleeves should be as long as possible, so that he never shows his fingers.

Apparations

Here the outward form is that of a ghost; but within is the heart of a man.

Such plays are generally in two parts. The beginning, in two or three sections, should be as short as possible. In the second half the shite (who has hitherto appeared to be a man) becomes definitely the ghost of a dead person.

Since no one has ever seen a real ghost from the Nether Regions, the actor may use his fancy, aiming only at the beautiful. To represent real life is far more difficult.

If ghosts are terrifying, they cease to be beautiful. For the terrifying and the beautiful are as far apart as black and white.

Child Plays

In plays where a lost child is found by its parents, the writer should not introduce a scene where they clutch and cling to one another, sobbing and weeping….

Plays in which child-characters occur, even if well done, are always apt to make the audience exclaim in disgust, “Don’t harrow our feelings in this way!”

Restraint

In representing anger the actor should yet retain some gentleness in his mood, else he will portray not anger but violence.

In representing the mysterious (yūgen) he must not forget the principle of energy.

When the body is in violent action, the hands and feet must move as though by stealth. When the feet are in lively motion, the body must be held in quietness. Such things cannot be explained in writing but must be shown to the actor by actual demonstration.

It is above all in “architecture,” in the relation of parts to the whole, that these poems are supreme. The early writers created a “form” or general pattern which the weakest writing cannot wholly rob of its beauty. The plays are like those carved lamp-bearing angels in the churches at Seville; a type of such beauty was created by a sculptor of the sixteenth century that even the most degraded modern descendant of these masterpieces retains a certain distinction of form.

First comes the jidai or opening-couplet, enigmatic, abrupt. Then in contrast to this vague shadow come the hard outlines of the waki’s exposition, the formal naming of himself, his origin and destination. Then, shadowy again, the “song of travel,” in which picture after picture dissolves almost before it is seen.

But all this has been mere introduction—the imagination has been quickened, the attention grasped in preparation for one thing only—the hero’s entry. In the “first chant,” in the dialogue which follows, in the successive dances and climax, this absolute mastery of construction is what has most struck me in reading the plays.

Again, Nō does not make a frontal attack on the emotions. It creeps at the subject warily. For the action, in the commonest class of play, does not take place before our eyes, but is lived through again in mimic and recital by the ghost of one of the participants in it. Thus we get no possibility of crude realities; a vision of life indeed, but painted with the colours of memory, longing or regret.

In a paper read before the Japan Society in 1919 I tried to illustrate this point by showing, perhaps in too fragmentary and disjointed a manner, how the theme of Webster’s “Duchess of Malfi” would have been treated by a Nō writer. I said then (and the Society kindly allows me to repeat those remarks):

The plot of the play is thus summarized by Rupert Brooke in his “John Webster and the Elizabethan Drama”: “The Duchess of Malfi is a young widow forbidden by her brothers, Ferdinand and the Cardinal, to marry again. They put a creature of theirs, Bosola, into her service as a spy. The Duchess loves and marries Antonio, her steward, and has three children. Bosola ultimately discovers and reports this. Antonio and the Duchess have to fly. The Duchess is captured, imprisoned and mentally tortured and put to death. Ferdinand goes mad. In the last Act he, the Cardinal, Antonio and Bosola are all killed with various confusions and in various horror.”

Just as Webster took his themes from previous works (in this case from Painter’s “Palace of Pleasure”), so the Nō plays took theirs from the Romances or “Monogatari.” Let us reconstruct the “Duchess” as a Nō play, using Webster’s text as our “Monogatari.”

Great simplification is necessary, for the Nō play corresponds in length to one act of our five-act plays, and has no space for divagations. The comic is altogether excluded, being reserved for the kyōgen or farces which are played as interludes between the Nō.

The persons need not be more than two—the Pilgrim, who will act the part of waki, and the Duchess, who will be shite or Protagonist. The chorus takes no part in the action, but speaks for the shite while she is miming the more engrossing parts of her rôle.

The Pilgrim comes on to the stage and first pronounces in his Jidai or preliminary couplet, some Buddhist aphorism appropriate to the subject of the play. He then names himself to the audience thus (in prose):

“I am a pilgrim from Rome. I have visited all the other shrines of Italy, but have never been to Loretto. I will journey once to the shrine of Loretto.”

Then follows (in verse) the “Song of Travel” in which the Pilgrim describes the scenes through which he passes on his way to the shrine. While he is kneeling at the shrine, Shite (the Protagonist) comes on to the stage. She is a young woman dressed, “contrary to the Italian fashion,” in a loose-bodied gown. She carries in her hand an unripe apricot. She calls to the Pilgrim and engages him in conversation. He asks her if it were not at this shrine that the Duchess of Malfi took refuge. The young woman answers with a kind of eager exaltation, her words gradually rising from prose to poetry. She tells the story of the Duchess’s flight, adding certain intimate touches which force the priest to ask abruptly, “Who is it that is speaking to me?”

And the girl shuddering (or it is hateful to a ghost to name itself) answers: “Hazukashi ya! I am the soul of the Duke Ferdinand’s sister, she that was once called Duchess of Malfi. Love still ties my soul to the earth. Toburai tabi-tamaye! Pray for me, oh, pray for my release!”

Here closes the first part of the play. In the second the young ghost, her memory quickened by the Pilgrim’s prayers (and this is part of the medicine of salvation), endures again the memory of her final hours. She mimes the action of kissing the hand (vide Act IV, Scene 1), finds it very cold:

I fear you are not well after your travel. Oh! horrible! What witchcraft does he practise, that he hath left A dead man’s hand here?

And each successive scene of the torture is so vividly mimed that though it exists only in the Protagonist’s brain, it is as real to the audience as if the figure of dead Antonio lay propped upon the stage, or as if the madmen were actually leaping and screaming before them.

Finally she acts the scene of her own execution:

Heaven-gates are not so highly arched

As princes’ palaces; they that enter there

Must go upon their knees. [She kneels.]

Come, violent death,

Serve for mandragora to make me sleep!

Go tell my brothers, when I am laid out,

They then may feed in quiet.

[She sinks her head and folds her hands.]

The chorus, taking up the word “quiet,” chant a phrase from the Hokkekyō: Sangai Mu-an, “In the Three Worlds there is no quietness or rest.”

But the Pilgrim’s prayers have been answered. Her soul has broken its bonds: is free to depart. The ghost recedes, grows dimmer and dimmer, till at last

use-ni-keri

use-ni-keri

it vanishes from sight.

Note on Buddhism

The Buddhism of the Nō plays is of the kind called the “Greater Vehicle,” which prevails in China, Japan and Tibet. Primitive Buddhism (the “Lesser Vehicle”), which survives in Ceylon and Burma, centres round the person of Shākyamuni, the historical Buddha, and uses Pāli as its sacred language. The “Greater Vehicle,” which came into being about the same time as Christianity and sprang from the same religious impulses, to a large extent replaces Shākyamuni by a timeless, ideal Buddha named Amida, “Lord of Boundless Light,” perhaps originally a sun-god, like Ormuzd of the Zoroastrians. Primitive Buddhism had taught that the souls of the faithful are absorbed into Nirvāna, in other words into Buddha. The “Greater Vehicle” promised to its adherents an after-life in Amida’s Western Paradise. It produced scriptures in the Sanskrit language, in which Shākyamuni himself describes this Western Land and recommends the worship of Amida; it inculcated too the worship of the Bodhisattvas, half-Buddhas, intermediaries between Buddha and man. These Bodhisattvas are beings who, though fit to receive Buddhahood, have of their own free will renounced it, that they may better alleviate the miseries of mankind.

Chief among them is Kwannon, called in India Avalokiteshvara, who appears in the world both in male and female form, but it is chiefly thought of as a woman in China and Japan; Goddess of Mercy, to whom men pray in war, storm, sickness or travail.

The doctrine of Karma and of the transmigration of souls was common both to the earlier and later forms of Buddhism. Man is born to an endless chain of re-incarnations, each one of which is, as it were, the fruit of seed sown in that which precedes.

The only escape from this “Wheel of Life and Death” lies in satori, “Enlightenment,” the realization that material phenomena are thoughts, not facts.

Each of the four chief sects which existed in medieval Japan had its own method of achieving this Enlightenment.

The Amidists sought to gain satori by the study of the Hokke Kyō, called in Sanskrit Saddharma Pundarika Sūtra or “Scripture of the Lotus of the True Law,” or even by the mere repetition of its complete title “Myōhō Renge Hokke Kyō.” Others of them maintained that the repetition of the formula “Praise to Amida Buddha” (Namu Amida Butsu) was in itself a sufficient means of salvation.

Once when Shākyamuni was preaching before a great multitude, he picked up a flower and twisted it in his fingers. The rest of his hearers saw no significance in the act and made no response; but the disciple Kāshyapa smiled.

In this brief moment a perception of transcendental truth had flashed from Buddha’s mind to the mind of his disciple. Thus Kāshyapa became the patriarch of the Zen Buddhists, who believe that Truth cannot be communicated by speech or writing, but that it lies hidden in the heart of each one of us and can be discovered by “Zen” or contemplative introspection.

At first sight there would not appear to be any possibility of reconciling the religion of the Zen Buddhists with that of the Amidists. Yet many Zen masters strove to combine the two faiths, teaching that Amida and his Western Paradise exist, not in time or space, but mystically enshrined in men’s hearts.

Zen denied the existence of Good and Evil, and was sometimes regarded as a dangerous sophistry by pious Buddhists of other sects, as, for example, in the story of Shunkwan and in The Hōka Priests, where the murderer’s interest in Zen doctrines is, I think, definitely regarded as a discreditable weakness and is represented as the cause of his undoing.

The only other play, among those I have here translated, which deals much with Zen tenets, is Sotoba Komachi. Here the priests represent the Shingon Shū or Mystic Sect, while Komachi, as becomes a poetess, defends the doctrines of Zen. For Zen was the religion of artists; it had inspired the painters and poets of the Sung dynasty in China; it was the religion of the great art-patrons who ruled Japan in the fifteenth century.

It was in the language of Zen that poetry and painting were discussed; and it was in a style tinged with Zen that Seami wrote of his own art. But the religion of the Nō plays is predominantly Amidist; it is the common, average Buddhism of medieval Japan.

I have said that the priests in Sotoba Komachi represent the Mystic Sect. The followers of this sect sought salvation by means of charms and spells, corruptions of Sanskrit formulae. Their principal Buddha was Dainichi, “The Great Sun.” To this sect belonged the Yamabushi, mountain ascetics referred to in Tanikō and other plays.

Mention must be made of the fusion between Buddhism and Shintō. The Tendai Sect which had its headquarters on Mount Hiyei preached an eclectic doctrine which aimed at becoming the universal religion of Japan. It combined the cults of native gods with a Buddhism tolerant in dogma, but magnificent in outward pomp, with a leaning towards the magical practices of Shingon.

The Little Saint of Yokawa in the play Aoi no Uye is an example of the Tendai ascetic, with his use of magical incantations.

Hatsuyuki appeared in “Poetry,” Chicago, and is here reprinted with the editor’s kind permission.

Atsumori, Ikuta, and Tsunemasa

In the eleventh century two powerful clans, the Taira and the Minamoto, contended for mastery. In 1181 Kiyomori the chief of the Tairas died, and from that time their fortunes declined. In 1183 they were forced to flee from Kyōto, carrying with them the infant Emperor. After many hardships and wanderings they camped on the shores of Suma, where they were protected by their fleet.

Early in 1184 the Minamotos attacked and utterly routed them at the Battle of Ichi-no-Tani, near the woods of Ikuta. At this battle fell Atsumori, the nephew of Kiyomori, and his brother Tsunemasa.

When Kumagai, who had slain Atsumori, bent over him to examine the body, he found lying beside him a bamboo-flute wrapped in brocade. He took the flute and gave it to his son.

The bay of Suma is associated in the mind of a Japanese reader not only with this battle but also with the stories of Prince Genji and Prince Yukihira.

“Atsumori” from The Nō Plays of Japan

Seami, translated by Arthur Waley

License: Public Domain

PERSONS

THE PRIEST RENSEI (formerly the warrior Kumaga).

A YOUNG REAPER, who turns out to be the ghost of Atsumori.

HIS COMPANION.

CHORUS.

PRIEST

Life is a lying dream, he only wakes

Who casts the World aside.

I am Kumagai no Naozane, a man of the country of Musashi.

I have left my home and call myself the priest Rensei; this I have done because of my grief at the death of Atsumori, who fell in battle by my hand. Hence it comes that I am dressed in priestly guise.And now I am going down to Ichi-no-Tani to pray for the salvation of Atsumori’s soul.

[He walks slowly across the stage, singing a song descriptive of his journey.]

I have come so fast that here I am already at Ichi-no-Tani, in the country of Tsu.

Truly the past returns to my mind as though it were a thing of to-day.

But listen! I hear the sound of a flute coming from a knoll of rising ground. I will wait here till the flute-player passes, and ask him to tell me the story of this place.

REAPERS [together]

To the music of the reaper’s flute

No song is sung

But the sighing of wind in the fields.

YOUNG REAPER

They that were reaping,

Reaping on that hill,

Walk now through the fields

Homeward, for it is dusk.

REAPERS [together]

From the sea of Suma back to my home.

This little journey, up to the hill

And down to the shore again, and up to the hill—

This is my life, and the sum of hateful tasks.

If one should ask me I too would answer

That on the shores of Suma I live in sadness.

Yet if any guessed my name,

Then might I too have friends.

But now from my deep misery

Even those that were dearest

Are grown estranged.

Here must I dwell abandoned

To one thought’s anguish:

That I must dwell here.

PRIEST

Hey, you reapers! I have a question to ask you.

YOUNG REAPER

Is it to us you are speaking? What do you wish to know?

PRIEST

Was it one of you who was playing on the flute just now?

YOUNG REAPER

Yes, it was we who were playing.

PRIEST

It was a pleasant sound, and all the pleasanter because one does not look for such music from men of your condition.

YOUNG REAPER

Unlooked for from men of our condition, you say!

Have you not read:—

“Do not envy what is above you

Nor despise what is below you”?

Moreover the songs of woodmen and the flute-playing of herdsmen,

Flute-playing even of reapers and songs of wood-fellers

Through poets’ verses are known to all the world.

Wonder not to hear among us

The sound of a bamboo-flute.

PRIEST

You are right. Indeed it is as you have told me.

Songs of woodmen and flute-playing of herdsmen…

REAPER

Flute-playing of reapers…

PRIEST

Songs of wood-fellers…

REAPER

Guide us on our passage through this sad world.

PRIEST

Song…

REAPER

And dance…

PRIEST

And the flute…

REAPER

And music of many instruments…

CHORUS

These are the pastimes that each chooses to his taste.

Of floating bamboo-wood

Many are the famous flutes that have been made;

Little-Branch and Cicada-Cage,

And as for the reaper’s flute, Its name is Green-leaf;

On the shore of Sumiyoshi

The Corean flute they play.

And here on the shore of Suma

On Stick of the Salt-kilns

The fishers blow their tune.

PRIEST

How strange it is! The other reapers have all gone home, but you alone stay loitering here. How is that?

REAPER

How is it, you ask? I am seeking for a prayer in the voice of the evening waves. Perhaps you will pray the Ten Prayers for me?

PRIEST

I can easily pray the Ten Prayers for you, if you will tell me who you are.

REAPER

To tell you the truth—I am one of the family of Lord Atsumori.

PRIEST

One of Atsumori’s family? How glad I am!

Then the priest joined his hands [he kneels down] and prayed:—

NAMU AMIDABU

Praise to Amida Buddha!

“If I attain to Buddhahood,

In the whole world and its ten spheres

Of all that dwell here none shall call on my name

And be rejected or cast aside.”

CHORUS

“Oh, reject me not!

One cry suffices for salvation,

Yet day and night

Your prayers will rise for me.

Happy am I, for though you know not my name,

Yet for my soul’s deliverance

At dawn and dusk henceforward I know that you will pray.”

So he spoke. Then vanished and was seen no more.

[Here follows the Interlude between the two Acts, in which a recitation concerning Atsumori’s death takes place. These interludes are subject to variation and are not considered part of the literary text of the play.]

PRIEST

Since this is so, I will perform all night the rites of prayer for the dead, and calling upon Amida’s name will pray again for the salvation of Atsumori.

[The ghost of Atsumori appears, dressed as a young warrior.]

ATSUMORI

Would you know who I am

That like the watchmen at Suma Pass

Have wakened at the cry of sea-birds roaming

Upon Awaji shore?

Listen, Rensei. I am Atsumori.

PRIEST

How strange! All this while I have never stopped beating my gong and performing the rites of the Law. I cannot for a moment have dozed, yet I thought that Atsumori was standing before me. Surely it was a dream.

ATSUMORI

Why need it be a dream?

It is to clear the karma of my waking life that

I am come here in visible form before you.

PRIEST

Is it not written that one prayer will wipe away ten thousand sins?

Ceaselessly I have performed the ritual of the

Holy Name that clears all sin away.

After such prayers, what evil can be left?

Though you should be sunk in sin as deep…

ATSUMORI

As the sea by a rocky shore,

Yet should I be salved by prayer.

PRIEST

And that my prayers should save you…

ATSUMORI

This too must spring

From kindness of a former life.

PRIEST

Once enemies …

ATSUMORI

But now…

PRIEST

In truth may we be named…

ATSUMORI

Friends in Buddha’s Law.

CHORUS

There is a saying, “Put away from you a wicked friend; summon to your side a virtuous enemy.” For you it was said, and you have proven it true.

And now come tell with us the tale of your confession, while the night is still dark.

Mount the tree-top that men may raise their eyes

And walk on upward paths;

He bids the moon in autumn waves be drowned

In token that he visits laggard men

And leads them out from valleys of despair.

ATSUMORI

Now the clan of Taira, building wall to wall,

Spread over the earth like the leafy branches of a great tree:

CHORUS

Yet their prosperity lasted but for a day;

It was like the flower of the convolvulus.

That glory flashes like sparks from flint-stone,

And after,—darkness.

Oh wretched, the life of men!

ATSUMORI

When they were on high they afflicted the humble;

When they were rich they were reckless in pride.

And so for twenty years and more

They ruled this land.

But truly a generation passes like the space of a dream.

The leaves of the autumn of Juyei

Were tossed by the four winds;

Scattered, scattered (like leaves too) floated their ships.

And they, asleep on the heaving sea, not even in dreams

Went back to home.

Caged birds longing for the clouds,—

Wild geese were they rather, whose ranks are broken

As they fly to southward on their doubtful journey.

So days and months went by; Spring came again

And for a little while

Here dwelt they on the shore of Suma

From the mountain behind us the winds blew down

Till the fields grew wintry again.

Our ships lay by the shore, where night and day

The sea-gulls cried and salt waves washed on our sleeves.

We slept with fishers in their huts

On pillows of sand.

We knew none but the people of Suma.

And when among the pine-trees

The evening smoke was rising,

Brushwood we gathered

And spread for carpet.

Sorrowful we lived

On the wild shore of Suma,

Till the clan Taira and all its princes

Were but villagers of Suma.

But on the night of the sixth day of the second month

My father Tsunemori gathered us together.

“To-morrow,” he said, “we shall fight our last fight.

To-night is all that is left us.”

We sang songs together, and danced.

PRIEST

Yes, I remember; we in our siege-camp

Heard the sound of music

Echoing from your tents that night;

There was the music of a flute…

ATSUMORI

The bamboo-flute! I wore it when I died.

PRIEST

We heard the singing…

ATSUMORI

Songs and ballads…

PRIEST

Many voices

ATSUMORI

Singing to one measure.

[Atsumori dances.]

First comes the Royal Boat.

CHORUS

The whole clan has put its boats to sea.

He runs to the shore.

But the Royal Boat and the soldiers’ boats

Have sailed far away.

ATSUMORI

What can he do?

He spurs his horse into the waves.

He is full of perplexity.

And then

CHORUS

He looks behind him and sees

That Kumagai pursues him;

He cannot escape.

Then Atsumori turns his horse

Knee-deep in the lashing waves,

And draws his sword.

Twice, three times he strikes; then, still saddled,

In close fight they twine; roll headlong together

Among the surf of the shore.

So Atsumori fell and was slain, but now the

Wheel of Fate Has turned and brought him back.

[Atsumori rises from the ground and advances toward the Priest with uplifted sword.]

“There is my enemy,” he cries, and would strike,

But the other is grown gentle

And calling on Buddha’s name

Has obtained salvation for his foe;

So that they shall be re-born together

On one lotus-seat.

“No, Rensei is not my enemy.

Pray for me again, oh pray for me again.”

“Ikuta” from The Nō Plays of Japan

Zembō Motoyasu (1453-1532),

translated by Arthur Waley

License: Public Domain

PERSONS

PRIEST (a follower of Hōnen Shōnin).

ATSUMORI’S CHILD.

ATSUMORI.

CHORUS.

PRIEST

I am one that serves Hōnen Shōnin of Kurodani; and as for this child here,—once when Hōnen was on a visit to the Temple of Kamo he saw a box lying under a trailing fir-tree; and when he raised the lid, what should he find inside but a lovely man-child one year old! It did not seem to be more than a common foundling, but my master in his compassion took the infant home with him. Ever since then he has had it in his care, doing all that was needful for it; and now the boy is over ten years old.

But it is a hard thing to have no father or mother, so one day after his preaching the Shōnin told the child’s story. And sure enough a young woman stepped out from among the hearers and said it was her child. And when he took her aside and questioned her, he found that the child’s father was Taira no Atsumori, who had fallen in battle at Ichi-no-Tani years ago. When the boy was told of this, he longed earnestly to see his father’s face, were it but in a dream, and the Shōnin bade him go and pray at the shrine of Kamo. He was to go every day for a week, and this is the last day.

That is why I have brought him out with me.

But here we are at the Kamo shrine.

Pray well, boy, pray well!

BOY

How fills my heart with awe

When I behold the crimson palisade

Of this abode of gods!

Oh may my heart be clean

And the God’s kindness deep

As its unfathomed waters. Show to me,

Though it were but in dream,

My father’s face and form.

Is not my heart so ground away with prayer,

So smooth that it will slip

Unfelt into the favour of the gods?

But thou too, Censor of our prayers,

God of Tadasu, on the gods prevail

That what I crave may be!

How strange! While I was praying I fell half-asleep and had a wonderful dream.

PRIEST

Tell me your wonderful dream.

BOY

A strange voice spoke to me from within the Treasure Hall, saying, “If you are wanting, though it were but in a dream, to see your father’s face, go down from here to the woods of Ikuta in the country of Settsu.” That is the marvellous dream I had.

PRIEST

It is indeed a wonderful message that the God has sent you. And why should I go back at once to Kurodani? I had best take you straight to the forest of Ikuta. Let us be going.

PRIEST [describing the journey]

From the shrine of Kamo,

From under the shadow of the hills,

We set out swiftly;

Past Yamazaki to the fog-bound

Shores of Minasé;

And onward where the gale

Tears travellers’ coats and winds about their bones.

“Autumn has come to woods where yesterday

We might have plucked the green.”

To Settsu, to those woods of Ikuta

Lo! We are come.

We have gone so fast that here we are already at the woods of Ikuta in the country of Settsu. I have heard tell in the Capital of the beauty of these woods and the river that runs through them. But what I see now surpasses all that I have heard.

Look! Those meadows must be the Downs of Ikuta. Let us go nearer and admire them.

But while we have been going about looking at one view and another, the day has dusked.

I think I see a light over there. There must be a house. Let us go to it and ask for lodging.

ATSUMORI [speaking from inside a hut]

Beauty, perception, knowledge, motion, consciousness,—

The Five Attributes of Being,—

All are vain mockery.

How comes it that men prize

So weak a thing as body?

For the soul that guards it from corruption

Suddenly to the night-moon flies,

And the poor naked ghost wails desolate

In the autumn wind.

Oh! I am lonely. I am lonely!

PRIEST

How strange! Inside that grass-hut I see a young soldier dressed in helmet and breastplate. What can he be doing there?

ATSUMORI

Oh foolish men, was it not to meet me that you came to this place? I am—oh! I am ashamed to say it,—I am the ghost of what once was … Atsumori.

BOY

Atsumori? My father…

CHORUS

And lightly he ran,

Plucked at the warrior’s sleeve,

And though his tears might seem like the long woe

Of nightingales that weep,

Yet were they tears of meeting-joy,

Of happiness too great for human heart.

So think we, yet oh that we might change

This fragile dream of joy

Into the lasting love of waking life!

ATSUMORI

Oh pitiful!

To see this child, born after me,

Darling that should be gay as a flower,

Walking in tattered coat of old black cloth.

Alas!

Child, when your love of me

Led you to Kamo shrine, praying to the God

That, though but in a dream,

You might behold my face,

The God of Kamo, full of pity, came

To Yama, king of Hell.

King Yama listened and ordained for me

A moment’s respite, but hereafter, never.

CHORUS

“The moon is sinking.

Come while the night is dark,” he said,

“I will tell my tale.”

ATSUMORI

When the house of Taira was in its pride,

When its glory was young,

Among the flowers we sported,

Among birds, wind and moonlight;

With pipes and strings, with song and verse

We welcomed Springs and Autumns.

Till at last, because our time was come,

Across the bridges of Kiso a host unseen

Swept and devoured us.

Then the whole clan

Our lord leading

Fled from the City of Flowers.

By paths untrodden

To the Western Sea our journey brought us.

Lakes and hills we crossed

Till we ourselves grew to be like wild men.

At last by mountain ways—

We too tossed hither and thither like its waves—

To Suma came we,

To the First Valley and the woods of Ikuta.

And now while all of us,

We children of Taira, were light of heart

Because our homes were near,

Suddenly our foes in great strength appeared.

CHORUS

Noriyori, Yoshitsune,—their hosts like clouds,

Like mists of spring.

For a little while we fought them,

But the day of our House was ended,

Our hearts weakened

That had been swift as arrows from the bowstring.

We scattered, scattered; till at last

To the deep waters of the Field of Life.

We came, but how we found there Death, not Life,

What profit were it to tell?

ATSUMORI

Who is that?

[Pointing in terror at a figure which he sees off the stage.]

Can it be Yama’s messenger? He comes to tell me that I have out-stayed my time. The Lord of Hell is angry: he asks why I am late?

CHORUS

So he spoke. But behold

Suddenly black clouds rise,

Earth and sky resound with the clash of arms;

War-demons innumerable

Flash fierce sparks from brandished spears.

ATSUMORI

The Shura foes who night and day

Come thick about me!

CHORUS

He waves his sword and rushes among them,

Hither and thither he runs slashing furiously;

Fire glints upon the steel.

But in a little while

The dark clouds recede;

The demons have vanished,

The moon shines unsullied;

The sky is ready for dawn.

ATSUMORA

Oh! I am ashamed…. And the child to see me so….

CHORUS

“To see my misery!

I must go back.

Oh pray for me; pray for me

When I am gone,” he said,

And weeping, weeping,

Dropped the child’s hand.

He has faded; he dwindles

Like the dew from rush-leaves

Of hazy meadows.

His form has vanished.

“Tsunemasa” from The Nō Plays of Japan

Seami, translated by Arthur Waley

License: Public Domain

GYŌKEI

I am Gyōkei, priest of the imperial temple Ninnaji. You must know that there was a certain prince of the House of Taira named Tsunemasa, Lord of Tajima, who since his boyhood has enjoyed beyond all precedent the favour of our master the Emperor. But now he has been killed at the Battle of the Western Seas.

It was to this Tsunemasa in his lifetime that the Emperor had given the lute called Green Hill. And now my master bids me take it and dedicate it to Buddha, performing a liturgy of flutes and strings for the salvation of Tsunemasa’s soul. And that was my purpose in gathering these musicians together.

Truly it is said that strangers who shelter under the same tree or draw water from the same pool will be friends in another life. How much the more must intercourse of many years, kindness and favour so deep…

Surely they will be heard,

The prayers that all night long

With due performance of rites

I have reverently repeated in this Palace

For the salvation of Tsunemasa

And for the awakening of his soul.

CHORUS

And, more than all, we dedicate

The lute Green Hill for this dead man;

While pipe and flute are joined to sounds of prayer.

For night and day the Gate of Law

Stands open and the Universal Road

Rejects no wayfarer.

TSUNEMASA [speaking off the stage]

“The wind blowing through withered trees: rain from a cloudless sky.

The moon shining on level sands: frost on a summer’s night.”

Frost lying… but I, because I could not lie at rest,

Am come back to the World for a while,

Like a shadow that steals over the grass.

I am like dews that in the morning

Still cling to the grasses. Oh pitiful the longing

That has beset me!

GYŌKEI

How strange! Within the flame of our candle that is burning low because the night is far spent, suddenly I seemed to see a man’s shadow dimly appearing. Who can be here?

TSUNEMASA [his shadow disappearing]

I am the ghost of Tsunemasa. The sound of your prayers has brought me in visible shape before you.

GYŌKEI

“I am the ghost of Tsunemasa,” he said, but when I looked to where the voice had sounded nothing was there, neither substance nor shadow!

TSUNEMASA

Only a voice,

GYŌKEI

A dim voice whispers where the shadow of a man Visibly lay, but when I looked

TSUNEMASA

It had vanished—

GYŌKEI

This flickering form …

TSUNEMASA

Like haze over the fields.

CHORUS

Only as a tricking magic,

A bodiless vision,

Can he hover in the world of his lifetime,

Swift-changing Tsunemasa.

By this name we call him, yet of the body

That men named so, what is left but longing?

What but the longing to look again, through the wall of death,

On one he loved?

“Sooner shall the waters in its garden cease to flow

Than I grow weary of living in the Palace of my Lord.”

Like a dream he has come,

Like a morning dream.

GYŌKEI

How strange! When the form of Tsunemasa had vanished, his voice lingered and spoke to me! Am I dreaming or waking? I cannot tell. But this I know,—that by the power of my incantations I have had converse with the dead. Oh! marvellous potency of the Law!

TSUNEMASA

It was long ago that I came to the Palace. I was but a boy then, but all the world knew me; for I was marked with the love of our Lord, with the favour of an Emperor. And, among many gifts, he gave to me once while I was in the World this lute which you have dedicated. My fingers were ever on its strings.

CHORUS

Plucking them even as now

This music plucks at your heart;

The sound of the plectrum, then as now

Divine music fulfilling

But this Tsunemasa,

Was he not from the days of his childhood pre-eminent

In faith, wisdom, benevolence,

Honour and courtesy; yet for his pleasure

Ever of birds and flowers,

Of wind and moonlight making

Ballads and songs to join their harmony

To pipes and lutes? So springs and autumns passed he.

But in a World that is as dew,

As dew on the grasses, as foam upon the waters,

What flower lasteth?

GYŌKEI

For the dead man’s sake we play upon this lute Green Hill that he loved when he was in the World. We follow the lute-music with a concord of many instruments.

[Music.]

TSUNEMASA

And while they played the dead man stole up behind them. Though he could not be seen by the light of the candle, they felt him pluck the lute-strings….

GYŌKEI

It is midnight. He is playing Yabanraku, the dance of midnight-revel. And now that we have shaken sleep from our eyes…

TSUNEMASA

The sky is clear, yet there is a sound as of sudden rain….

GYŌKEI

Rain beating carelessly on trees and grasses. What season’s music ought we to play?

TSUNEMASA

No. It is not rain. Look! At the cloud’s fringe

CHORUS

The moon undimmed

Hangs over the pine-woods of Narabi Hills.

It was the wind you heard;

The wind blowing through the pine-leaves

Pattered, like the falling of winter rain.

O wonderful hour!

“The big strings crashed and sobbed

Like the falling of winter rain.

And the little strings whispered secretly together.

The first and second string

Were like a wind sweeping through pine-woods,

Murmuring disjointedly.

The third and fourth string

Were like the voice of a caged stork

Crying for its little ones at night

The night must not cease.

The cock shall not crow

And put an end to his wandering.

TSUNEMASA

CHORUS

Shakes the autumn clouds from the mountain-side.”

The phœnix and his mate swoop down

Charmed by its music, beat their wings

And dance in rapture, perched upon the swaying boughs

Of kiri and bamboo.

[Dance.]

TSUNEMASA

Oh terrible anguish!

For a little while I was back in the World and my heart set on its music, on revels of midnight. But now the hate is rising in me….

GYŌKEI

The shadow that we saw before is still visible. Can it be Tsunemasa?

TSUNEMASA

Oh! I am ashamed; I must not let them see me. Put out your candle.

CHORUS

“Let us turn away from the candle and watch together

The midnight moon.”

Lo, he who holds the moon,

The god Indra, in battle appeareth

Warring upon demons.

Fire leaps from their swords,

The sparks of their own anger fall upon them like rain.

To wound another he draws his sword,

But it is from his own flesh

That the red waves flow;

Like flames they cover him.

“Oh, I am ashamed of the woes that consume me.

No man must see me.

I will put out the candle!” he said;

For a foolish man is like a summer moth that flies into the flame.

The wind that blew out the candle

Carried him away.

In the darkness his ghost has vanished.

The shadow of his ghost has vanished.