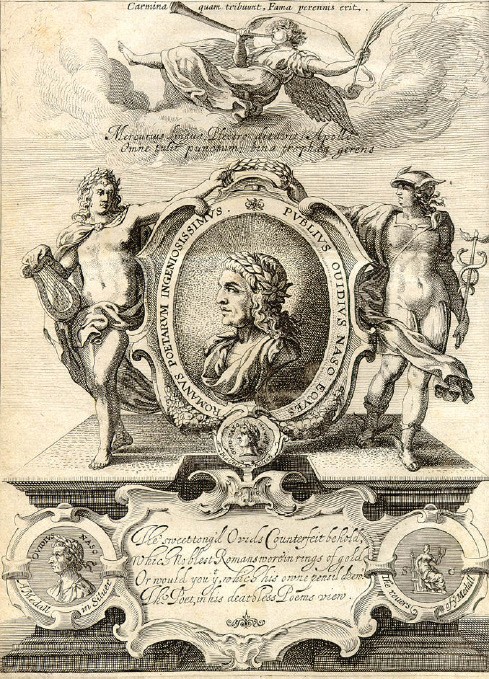

Metamorphoses

Ovid (43 B.C.E.-17 C.E.)

Published 8 C.E.

Rome

Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a collection of many Greek and Roman myths, is written by a master poet of the ancient world. From the creation of the world to the apotheosis of Julius Caesar, Ovid traces the course of mythological history, putting together a narrative based on previous written and oral sources. In the Aeneid of Virgil, Ovid’s older contemporary epic poet, the gods were portrayed as guiding history toward an end goal (the creation of Rome) with foresight and planning. In the Metamorphoses, Ovid demonstrates how the traditional stories reveal that there is very little planning in the actions of the gods, who often are motivated by lust or pride. His irreverent view of the world, combined with his previous (sometimes risqué) love poetry, probably led to his exile by Emperor Augustus in the same year that his Metamorphoses was published. In the Middle Ages, Ovid’s Metamorphoses was widely translated, although often with “moralized” notes alongside the text that imposed allegorical interpretations on the stories. For most subsequent authors, the Metamorphoses became the source book on Greek and Roman mythology.

Metamorphoses

Ovid, translated by Anthony S. KlinE133

Edited, compiled, and annotated by Rhonda L. Kelley

License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Book 1

The Primal Chaos

I want to speak about bodies changed into new forms. You, gods, since you are the ones who alter these, and all other things, inspire my attempt, and spin out a continuous thread of words, from the world’s first origins to my own time.

Before there was earth or sea or the sky that covers everything, Nature appeared the same throughout the whole world: what we call chaos: a raw confused mass, nothing but inert matter, badly combined discordant atoms of things, confused in the one place. There was no Titan134 yet, shining his light on the world, or waxing Phoebe135 renewing her white horns, or the earth hovering in surrounding air balanced by her own weight, or watery Amphitrite136 stretching out her arms along the vast shores of the world. Though there was land and sea and air, it was unstable land, unswimmable water, air needing light. Nothing retained its shape, one thing obstructed another, because in the one body, cold fought with heat, moist with dry, soft with hard, and weight with weightless things.

Separation of the elements

This conflict was ended by a god and a greater order of nature, since he split off the earth from the sky, and the sea from the land, and divided the transparent heavens from the dense air. When he had disentangled the elements, and freed them from the obscure mass, he fixed them in separate spaces in harmonious peace. The weightless fire, that forms the heavens, darted upwards to make its home in the furthest heights. Next came air in lightness and place. Earth, heavier than either of these, drew down the largest elements, and was compressed by its own weight. The surrounding water took up the last space and enclosed the solid world.

The earth and sea. The five zones.

When whichever god it was had ordered and divided the mass, and collected it into separate parts, he first gathered the earth into a great ball so that it was uniform on all sides. Then he ordered the seas to spread and rise in waves in the flowing winds and pour around the coasts of the encircled land. He added springs and standing pools and lakes, and contained in shelving banks the widely separated rivers, some of which are swallowed by the earth itself, others of which reach the sea and entering the expanse of open waters beat against coastlines instead of riverbanks. He ordered the plains to extend, the valleys to subside, leaves to hide the trees, stony mountains to rise: and just as the heavens are divided into two zones to the north and two to the south, with a fifth and hotter between them, so the god carefully marked out the enclosed matter with the same number, and described as many regions on the earth. The equatorial zone is too hot to be habitable; the two poles are covered by deep snow; and he placed two regions between and gave them a temperate climate mixing heat and cold.

The four winds

Air overhangs them, heavier than fire by as much as water’s weight is lighter than earth. There he ordered the clouds and vapours to exist, and thunder to shake the minds of human beings, and winds that create lightning-bolts and flashes.

The world’s maker did not allow these, either, to possess the air indiscriminately; as it is they are scarcely prevented from tearing the world apart, each with its blasts steering a separate course: like the discord between brothers. Eurus, the east wind, drew back to the realms of Aurora,137 to Nabatea, Persia, and the heights under the morning light: Evening, and the coasts that cool in the setting sun, are close to Zephyrus, the west wind. Chill Boreas, the north wind, seized Scythia and the seven stars of the Plough:138 while the south wind, Auster, drenches the lands opposite with incessant clouds and rain. Above these he placed the transparent, weightless heavens free of the dross of earth.

Humankind

He had barely separated out everything within fixed limits when the constellations that had been hidden for a long time in dark fog began to blaze out throughout the whole sky. And so that no region might lack its own animate beings, the stars and the forms of gods occupied the floor of heaven, the sea gave a home to the shining fish, earth took the wild animals, and the light air flying things.

As yet there was no animal capable of higher thought that could be ruler of all the rest. Then Humankind was born. Either the creator god, source of a better world, seeded it from the divine, or the newborn earth just drawn from the highest heavens still contained fragments related to the skies, so that Prometheus,139 blending them with streams of rain, moulded them into an image of the all-controlling gods. While other animals look downwards at the ground, he gave human beings an upturned aspect, commanding them to look towards the skies, and, upright, raise their face to the stars. So the earth, that had been, a moment ago, uncarved and imageless, changed and assumed the unknown shapes of human beings.

The Golden Age

This was the Golden Age that, without coercion, without laws, spontaneously nurtured the good and the true. There was no fear or punishment: there were no threatening words to be read, fixed in bronze, no crowd of suppliants fearing the judge’s face: they lived safely without protection. No pine tree felled in the mountains had yet reached the flowing waves to travel to other lands: human beings only knew their own shores. There were no steep ditches surrounding towns, no straight war-trumpets, no coiled horns, no swords and helmets. Without the use of armies, people passed their lives in gentle peace and security. The earth herself also, freely, without the scars of ploughs, untouched by hoes, produced everything from herself. Contented with food that grew without cultivation, they collected mountain strawberries and the fruit of the strawberry tree, wild cherries, blackberries clinging to the tough brambles, and acorns fallen from Jupiter’s spreading oak-tree. Spring was eternal, and gentle breezes caressed with warm air the flowers that grew without being seeded. Then the untilled earth gave of its produce and, without needing renewal, the fields whitened with heavy ears of corn. Sometimes rivers of milk flowed, sometimes streams of nectar, and golden honey trickled from the green holm oak.

The Silver Age

When Saturn140 was banished to gloomy Tartarus,141 and Jupiter ruled the world, then came the people of the age of silver that is inferior to gold, more valuable than yellow bronze. Jupiter shortened spring’s first duration and made the year consist of four seasons, winter, summer, changeable autumn, and brief spring. Then parched air first glowed white scorched with the heat, and ice hung down frozen by the wind. Then houses were first made for shelter: before that homes had been made in caves, and dense thickets, or under branches fastened with bark. Then seeds of corn were first buried in the long furrows, and bullocks groaned, burdened under the yoke.

The Bronze Age

Third came the people of the bronze age, with fiercer natures, readier to indulge in savage warfare, but not yet vicious. The harsh iron age was last. Immediately every kind of wickedness erupted into this age of baser natures: truth, shame and honour vanished; in their place were fraud, deceit, and trickery, violence and pernicious desires. They set sails to the wind, though as yet the seamen had poor knowledge of their use, and the ships’ keels that once were trees standing amongst high mountains, now leaped through uncharted waves. The land that was once common to all, as the light of the sun is, and the air, was marked out, to its furthest boundaries, by wary surveyors. Not only did they demand the crops and the food the rich soil owed them, but they entered the bowels of the earth, and excavating brought up the wealth it had concealed in Stygian142 shade, wealth that incites men to crime. And now harmful iron appeared, and gold more harmful than iron. War came, whose struggles employ both, waving clashing arms with bloodstained hands. They lived on plunder: friend was not safe with friend, relative with relative, kindness was rare between brothers. Husbands longed for the death of their wives, wives for the death of their husbands. Murderous stepmothers mixed deadly aconite, and sons inquired into their father’s years before their time. Piety was dead, and virgin Astraea,143 last of all the immortals to depart, herself abandoned the blood-drenched earth.

The giants

Rendering the heights of heaven no safer than the earth, they say the giants attempted to take the Celestial kingdom, piling mountains up to the distant stars. Then the all-powerful father of the gods hurled his bolt of lightning, fractured Olympus and threw Mount Pelion down from Ossa below. Her sons’ dreadful bodies, buried by that mass, drenched Earth with streams of blood, and they say she warmed it to new life, so that a trace of her children might remain, transforming it into the shape of human beings. But these progeny also despising the gods were savage, violent, and eager for slaughter, so that you might know they were born from blood.

When Saturn’s son, the father of the gods, saw this from his highest citadel, he groaned, and recalling the vile feast at Lycaon’s table, so recent it was still unknown, his mind filled with a great anger fitting for Jupiter, and he called the gods to council, a summons that brooked no delay.

There is a high track, seen when the sky is clear, called the Milky Way, and known for its brightness. This way the gods pass to the palaces and halls of the mighty Thunderer. To right and left are the houses of the greater gods, doors open and crowded. The lesser gods live elsewhere. Here the powerful and distinguished have made their home. This is the place, if I were to be bold, I would not be afraid to call high heaven’s Palatine.144

Jupiter threatens to destroy humankind

When the gods had taken their seats in the marble council chamber their king, sitting high above them, leaning on his ivory sceptre, shook his formidable mane three times and then a fourth, disturbing the earth, sea and stars. Then he opened his lips in indignation and spoke. ‘I was not more troubled than I am now concerning the world’s sovereignty than when each of the snake-footed giants prepared to throw his hundred arms around the imprisoned sky. Though they were fierce enemies, still their attack came in one body and from one source. Now I must destroy the human race, wherever Nereus sounds, throughout the world. I swear it by the infernal streams, that glide below the earth through the Stygian groves. All means should first be tried, but the incurable flesh must be excised by the knife, so that the healthy part is not infected. Mine are the demigods, the wild spirits, nymphs, fauns and satyrs,145 and sylvan146 deities of the hills. Since we have not yet thought them worth a place in heaven let us at least allow them to live in safety in the lands we have given them. Perhaps you gods believe they will be safe, even when Lycaon,147 known for his savagery, plays tricks against me, who holds the thunderbolt, and reigns over you.’

Lycaon is turned into a wolf

All the gods murmured aloud and, zealously and eagerly, demanded punishment of the man who committed such actions. When the impious band of conspirators148 were burning to drown the name of Rome in Caesar’s blood, the human race was suddenly terrified by fear of just such a disaster, and the whole world shuddered with horror. Your subjects’ loyalty is no less pleasing to you, Augustus,149 than theirs was to Jupiter. After he had checked their murmuring with voice and gesture, they were all silent. When the noise had subsided, quieted by his royal authority, Jupiter again broke the silence with these words: ‘Have no fear, he has indeed been punished, but I will tell you his crime, and what the penalty was. News of these evil times had reached my ears. Hoping it false I left Olympus’ heights, and travelled the earth, a god in human form. It would take too long to tell what wickedness I found everywhere. Those rumours were even milder than the truth. I had crossed Maenala, those mountains bristling with wild beasts’ lairs, Cyllene, and the pinewoods of chill Lycaeus. Then, as the last shadows gave way to night, I entered the inhospitable house of the Arcadian king. I gave them signs that a god had come, and the people began to worship me. At first Lycaon ridiculed their piety, then exclaimed ‘I will prove by a straightforward test whether he is a god or a mortal. The truth will not be in doubt.’ He planned to destroy me in the depths of sleep, unexpectedly, by night. That is how he resolved to prove the truth. Not satisfied with this he took a hostage sent by the Molossi, opened his throat with a knife, and made some of the still warm limbs tender in seething water, roasting others in the fire. No sooner were these placed on the table than I brought the roof down on the household gods, with my avenging flames, those gods worthy of such a master. He himself ran in terror, and reaching the silent fields howled aloud, frustrated of speech. Foaming at the mouth, and greedy as ever for killing, he turned against the sheep, still delighting in blood. His clothes became bristling hair, his arms became legs. He was a wolf, but kept some vestige of his former shape. There were the same grey hairs, the same violent face, the same glittering eyes, the same savage image. One house has fallen, but others deserve to also. Wherever the earth extends the avenging furies rule. You would think men were sworn to crime! Let them all pay the penalty they deserve, and quickly. That is my intent.’

Jupiter invokes the floodwaters

When he had spoken, some of the gods encouraged Jupiter’s anger, shouting their approval of his words, while others consented silently. They were all saddened though at this destruction of the human species, and questioned what the future of the world would be free of humanity. Who would honour their altars with incense? Did he mean to surrender the world to the ravages of wild creatures? In answer the king of the gods calmed their anxiety, the rest would be his concern, and he promised them a people different from the first, of a marvellous creation.

Now he was ready to hurl his lightning-bolts at the whole world but feared that the sacred heavens might burst into flame from the fires below, and burn to the furthest pole: and he remembered that a time was fated to come when sea and land, and the untouched courts of the skies would ignite, and the troubled mass of the world be besieged by fire. So he set aside the weapons the Cyclopes150 forged, and resolved on a different punishment, to send down rain from the whole sky and drown humanity beneath the waves.

Straight away he shut up the north winds in Aeolus’151 caves, with the gales that disperse the gathering clouds, and let loose the south wind, he who flies with dripping wings, his terrible aspect shrouded in pitch-black darkness. His beard is heavy with rain, water streams from his grey hair, mists wreathe his forehead, and his feathers and the folds of his robes distil the dew. When he crushes the hanging clouds in his outstretched hand there is a crash, and the dense vapours pour down rain from heaven. Iris, Juno’s messenger, dressed in the colours of the rainbow, gathers water and feeds it back to the clouds. The cornfields are flattened and saddening the farmers, the crops, the object of their prayers, are ruined, and the long year’s labour wasted.

The Flood

Jupiter’s anger is not satisfied with only his own aerial waters: his brother the sea-god helps him, with the ocean waves. He calls the rivers to council, and when they have entered their ruler’s house, says ‘Now is not the time for long speeches! Exert all your strength. That is what is needed. Throw open your doors, drain the dams, and loose the reins of all your streams!’ Those are his commands. The rivers return and uncurb their fountains’ mouths, and race an unbridled course to the sea.

Neptune himself strikes the ground with his trident, so that it trembles, and with that blow opens up channels for the waters. Overflowing, the rivers rush across the open plains, sweeping away at the same time not just orchards, flocks, houses and human beings, but sacred temples and their contents. Any building that has stood firm, surviving the great disaster undamaged, still has its roof drowned by the highest waves, and its towers buried below the flood. And now the land and sea are not distinct, all is the sea, the sea without a shore.

The world is drowned

There one man escapes to a hilltop, while another seated in his rowing boat pulls the oars over places where lately he was ploughing. One man sails over his cornfields or over the roof of his drowned farmhouse, while another man fishes in the topmost branches of an elm. Sometimes, by chance, an anchor embeds itself in a green meadow, or the curved boats graze the tops of vineyards. Where lately lean goats browsed shapeless seals play. The Nereids152 are astonished to see woodlands, houses and whole towns under the water. There are dolphins in the trees: disturbing the upper branches and stirring the oak-trees as they brush against them. Wolves swim among the sheep, and the waves carry tigers and tawny lions. The boar has no use for his powerful tusks, the deer for its quick legs, both are swept away together, and the circling bird, after a long search for a place to land, falls on tired wings into the water. The sea in unchecked freedom has buried the hills, and fresh waves beat against the mountaintops. The waters wash away most living things, and those the sea spares, lacking food, are defeated by slow starvation.

Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha

Phocis, a fertile country when it was still land, separates Aonia from Oeta, though at that time it was part of the sea, a wide expanse of suddenly created water. There Mount Parnassus lifts its twin steep summits to the stars, its peaks above the clouds. When Deucalion and his wife landed here in their small boat, everywhere else being drowned by the waters, they worshipped the Corycian nymphs, the mountain gods, and the goddess of the oracles, prophetic Themis. No one was more virtuous or fonder of justice than he was, and no woman showed greater reverence for the gods. When Jupiter saw the earth covered with the clear waters, and that only one man was left of all those thousands of men, only one woman left of all those thousands of women, both innocent and both worshippers of the gods, he scattered the clouds and mist, with the north wind, and revealed the heavens to the earth and the earth to the sky. It was no longer an angry sea, since the king of the oceans putting aside his three-pronged spear calmed the waves, and called sea-dark Triton,153 showing from the depths his shoulders thick with shells, to blow into his echoing conch and give the rivers and streams the signal to return. He lifted the hollow shell that coils from its base in broad spirals, that shell that filled with his breath in mid-ocean makes the eastern and the western shores sound. So now when it touched the god’s mouth, and dripping beard, and sounded out the order for retreat, it was heard by all the waters on earth and in the ocean, and all the waters hearing it were checked. Now the sea has shorelines, the brimming rivers keep to their channels, the floods subside, and hills appear. Earth rises, the soil increasing as the water ebbs, and finally the trees show their naked tops, the slime still clinging to their leaves.

They ask Themis for help

The world was restored. But when Deucalion saw its emptiness, and the deep silence of the desolate lands, he spoke to Pyrrha, through welling tears. ‘Wife, cousin, sole surviving woman, joined to me by our shared race, our family origins, then by the marriage bed, and now joined to me in danger, we two are the people of all the countries seen by the setting and the rising sun, the sea took all the rest. Even now our lives are not guaranteed with certainty: the storm clouds still terrify my mind. How would you feel now, poor soul, if the fates had willed you to be saved, but not me? How could you endure your fear alone? Who would comfort your tears? Believe me, dear wife, if the sea had you, I would follow you, and the sea would have me too. If only I, by my father’s arts, could recreate earth’s peoples, and breathe life into the shaping clay! The human race remains in us. The gods willed it that we are the only examples of mankind left behind.’ He spoke and they wept, resolving to appeal to the sky-god, and ask his help by sacred oracles. Immediately they went side by side to the springs of Cephisus that, though still unclear, flowed in its usual course. When they had sprinkled their heads and clothing with its watery libations, they traced their steps to the temple of the sacred goddess, whose pediments were green with disfiguring moss, her altars without fire. When they reached the steps of the sanctuary they fell forward together and lay prone on the ground, and kissing the cold rock with trembling lips, said ‘If the gods wills soften, appeased by the prayers of the just, if in this way their anger can be deflected, Themis tell us by what art the damage to our race can be repaired, and bring help, most gentle one, to this drowned world!’

The human race is re-created

The goddess was moved, and uttered oracular speech: ‘Leave the temple and with veiled heads and loosened clothes throw behind you the bones of your great mother!’ For a long time they stand there, dumbfounded. Pyrrha is first to break the silence: she refuses to obey the goddess’ command. Her lips trembling she asks for pardon, fearing to offend her mother’s spirit by scattering her bones. Meanwhile they reconsider the dark words the oracle gave, and their uncertain meaning, turning them over and over in their minds. Then Prometheus’ son154 comforted Epimetheus’ daughter155 with quiet words: ‘Either this idea is wrong, or, since oracles are godly and never urge evil, our great mother must be the earth: I think the bones she spoke about are stones in the body of the earth. It is these we are told to throw behind us.’

Though the Titan’s daughter is stirred by her husband’s thoughts, still hope is uncertain: they are both so unsure of the divine promptings; but what harm can it do to try? They descended the steps, covered their heads and loosened their clothes, and threw the stones needed behind them. The stones, and who would believe it if it were not for ancient tradition, began to lose their rigidity and hardness, and after a while softened, and once softened acquired new form. Then after growing, and ripening in nature, a certain likeness to a human shape could be vaguely seen, like marble statues at first inexact and roughly carved. The earthy part, however, wet with moisture, turned to flesh; what was solid and inflexible mutated to bone; the veins stayed veins; and quickly, through the power of the gods, stones the man threw took on the shapes of men, and women were remade from those thrown by the woman. So the toughness of our race, our ability to endure hard labour, and the proof we give of the source from which we are sprung.

Other species are generated

Earth spontaneously created other diverse forms of animal life. After the remaining moisture had warmed in the sun’s fire, the wet mud of the marshlands swelled with heat, and the fertile seeds of things, nourished by life-giving soil as if in a mother’s womb, grew, and in time acquired a nature. So, when the seven-mouthed Nile retreats from the drowned fields and returns to its former bed, and the fresh mud boils in the sun, farmers find many creatures as they turn the lumps of earth. Amongst them they see some just spawned, on the edge of life, some with incomplete bodies and number of limbs, and often in the same matter one part is alive and the other is raw earth. In fact when heat and moisture are mixed they conceive, and from these two things the whole of life originates. And though fire and water fight each other, heat and moisture create everything, and this discordant union is suitable for growth. So when the earth muddied from the recent flood glowed again heated by the deep heaven-sent light of the sun she produced innumerable species, partly remaking previous forms, partly creating new monsters.

Apollo kills the Python and sees Daphne

Indeed, though she would not have desired to, she then gave birth to you, great Python, covering so great an area of the mountain slopes, a snake not known before, a terror to the new race of men. The archer god, with lethal shafts that he had only used before on fleeing red deer and roe deer, with a thousand arrows, almost emptying his quiver, destroyed the creature, the venom running out from its black wounds. Then he founded the sacred Pythian games,156 celebrated by contests, named from the serpent he had conquered. There the young winners in boxing, in foot and chariot racing, were honoured with oak wreaths. There was no laurel as yet, so Apollo crowned his temples, his handsome curling hair, with leaves of any tree.

Apollo’s first love was Daphne, daughter of Peneus, and not through chance but because of Cupid’s fierce anger. Recently the Delian god, exulting at his victory over the serpent, had seen him bending his tightly strung bow and said ‘Impudent boy, what are you doing with a man’s weapons? That one is suited to my shoulders, since I can hit wild beasts of a certainty, and wound my enemies, and not long ago destroyed with countless arrows the swollen Python that covered many acres with its plague-ridden belly. You should be intent on stirring the concealed fires of love with your burning brand, not laying claim to my glories!’ Venus’ son replied ‘You may hit every other thing Apollo, but my bow will strike you: to the degree that all living creatures are less than gods, by that degree is your glory less than mine.’ He spoke, and striking the air fiercely with beating wings, he landed on the shady peak of Parnassus, and took two arrows with opposite effects from his full quiver: one kindles love, the other dispels it. The one that kindles is golden with a sharp glistening point, the one that dispels is blunt with lead beneath its shaft. With the second he transfixed Peneus’ daughter, but with the first he wounded Apollo piercing him to the marrow of his bones.

Apollo pursues Daphne

Now the one loved, and the other fled from love’s name, taking delight in the depths of the woods, and the skins of the wild beasts she caught, emulating virgin Diana,157 a careless ribbon holding back her hair. Many courted her, but she, averse to being wooed, free from men and unable to endure them, roamed the pathless woods, careless of Hymen158 or Amor,159 or whatever marriage might be. Her father often said ‘Girl you owe me a son-in-law’, and again often ‘Daughter, you owe me grandsons.’ But, hating the wedding torch as if it smacked of crime she would blush red with shame all over her beautiful face, and clinging to her father’s neck with coaxing arms, she would say ‘ Dearest father, let me be a virgin forever! Diana’s father granted it to her.’ He yields to that plea, but your beauty itself, Daphne, prevents your wish, and your loveliness opposes your prayer.

Apollo loves her at first sight, and desires to wed her, and hopes for what he desires, but his own oracular powers fail him. As the light stubble of an empty cornfield blazes; as sparks fire a hedge when a traveller, by mischance, lets them get too close, or forgets them in the morning; so the god was altered by the flames, and all his heart burned, feeding his useless desire with hope. He sees her disordered hair hanging about her neck and sighs ‘What if it were properly dressed?’ He gazes at her eyes sparkling with the brightness of starlight. He gazes on her lips, where mere gazing does not satisfy. He praises her wrists and hands and fingers, and her arms bare to the shoulder: whatever is hidden, he imagines more beautiful. But she flees swifter than the lightest breath of air, and resists his words calling her back again.

Apollo begs Daphne to yield to him

‘Wait nymph, daughter of Peneus, I beg you! I who am chasing you am not your enemy. Nymph, Wait! This is the way a sheep runs from the wolf, a deer from the mountain lion, and a dove with fluttering wings flies from the eagle: everything flies from its foes, but it is love that is driving me to follow you! Pity me! I am afraid you might fall headlong or thorns undeservedly scar your legs and I be a cause of grief to you! These are rough places you run through. Slow down, I ask you, check your flight, and I too will slow. At least enquire whom it is you have charmed. I am no mountain man, no shepherd, no rough guardian of the herds and flocks. Rash girl, you do not know, you cannot realise, who you run from, and so you run. Delphi’s lands are mine, Claros and Tenedos, and Patara acknowledges me king. Jupiter is my father. Through me what was, what is, and what will be, are revealed. Through me strings sound in harmony, to song. My aim is certain, but an arrow truer than mine, has wounded my free heart! The whole world calls me the bringer of aid; medicine is my invention; my power is in herbs. But love cannot be healed by any herb, nor can the arts that cure others cure their lord!’

Daphne becomes the laurel bough

He would have said more as timid Daphne ran, still lovely to see, leaving him with his words unfinished. The winds bared her body, the opposing breezes in her way fluttered her clothes, and the light airs threw her streaming hair behind her, her beauty enhanced by flight. But the young god could no longer waste time on further blandishments, urged on by Amor, he ran on at full speed. Like a hound of Gaul starting a hare in an empty field, that heads for its prey, she for safety: he, seeming about to clutch her, thinks now, or now, he has her fast, grazing her heels with his outstretched jaws, while she uncertain whether she is already caught, escaping his bite, spurts from the muzzle touching her. So the virgin and the god: he driven by desire, she by fear. He ran faster, Amor giving him wings, and allowed her no rest, hung on her fleeing shoulders, breathed on the hair flying round her neck. Her strength was gone, she grew pale, overcome by the effort of her rapid flight, and seeing Peneus’ waters near cried out ‘Help me father! If your streams have divine powers change me, destroy this beauty that pleases too well!’ Her prayer was scarcely done when a heavy numbness seized her limbs, thin bark closed over her breast, her hair turned into leaves, her arms into branches, her feet so swift a moment ago stuck fast in slow-growing roots, her face was lost in the canopy. Only her shining beauty was left.

Apollo honours Daphne

Even like this Apollo loved her and, placing his hand against the trunk, he felt her heart still quivering under the new bark. He clasped the branches as if they were parts of human arms, and kissed the wood. But even the wood shrank from his kisses, and the god said ‘Since you cannot be my bride, you must be my tree! Laurel, with you my hair will be wreathed, with you my lyre, with you my quiver. You will go with the Roman generals when joyful voices acclaim their triumph, and the Capitol witnesses their long processions. You will stand outside Augustus’ doorposts, a faithful guardian, and keep watch over the crown of oak between them. And just as my head with its uncropped hair is always young, so you also will wear the beauty of undying leaves.’ Paean had done: the laurel bowed her newly made branches, and seemed to shake her leafy crown like a head giving consent.

Inachus mourns for Io

There is a grove in Haemonia, closed in on every side by wooded cliffs. They call it Tempe. Through it the river Peneus rolls, with foaming waters, out of the roots of Pindus, and in its violent fall gathers clouds, driving the smoking mists along, raining down spray onto the tree tops, and deafening remoter places with its roar. Here is the house, the home, the innermost sanctuary of the great river. Seated here, in a rocky cavern, he laid down the law to the waters and the nymphs who lived in his streams. Here the rivers of his own country first met, unsure whether to console with or celebrate Daphne’s father: Spercheus among poplars, restless Enipeus, gentle Amphrysus, Aeas and ancient Apidanus; and then later all the others that, whichever way their force carries them, bring down their weary wandering waters to the sea. Only Inachus is missing, but hidden in the deepest cave he swells his stream with tears, and in utter misery laments his lost daughter, Io, not knowing if she is alive or among the shades. Since he cannot find her anywhere, he imagines her nowhere, and his heart fears worse than death.

Jupiter’s rape of Io

Jupiter first saw her returning from her father’s stream, and said ‘Virgin, worthy of Jupiter himself, who will make some unknown man happy when you share his bed, while it is hot and the sun is at the highest point of its arc, find shade in the deep woods! (and he showed her the woods’ shade). But if you are afraid to enter the wild beasts’ lairs, you can go into the remote woods in safety, protected by a god, and not by any lesser god, but by the one who holds the sceptre of heaven in his mighty hand, and who hurls the flickering bolts of lightning. Do not fly from me!’ She was already in flight. She had left behind Lerna’s pastures, and the Lyrcean plain’s wooded fields, when the god hid the wide earth in a covering of fog, caught the fleeing girl, and raped her.

Jupiter transforms Io to a heifer

Meanwhile Juno looked down into the heart of Argos, surprised that rapid mists had created night in shining daylight. She knew they were not vapours from the river, or breath from the damp earth. She looked around to see where her husband was, knowing by now the intrigues of a spouse so often caught in the act. When she could not find him in the skies, she said ‘Either I am wrong, or being wronged’ and gliding down from heaven’s peak, she stood on earth ordering the clouds to melt. Jupiter had a presage of his wife’s arrival and had changed Inachus’ daughter into a gleaming heifer. Even in that form she was beautiful. Juno approved the animal’s looks, though grudgingly, asking, then, whose she was, where from, what herd, as if she did not know. Jupiter, to stop all inquiry, lied, saying she had been born from the earth. Then Juno claimed her as a gift. What could he do? Cruel to sacrifice his love, but suspicious not to. Shame urges him to it, Amor urges not. Amor would have conquered Shame, but if he refused so slight a gift as a heifer to the companion of his race and bed, it might appear no heifer!

Juno claims Io and Argus guards her

Though her rival was given up the goddess did not abandon her fears at once, cautious of Jupiter and afraid of his trickery, until she had given Io into Argus’ keeping, that son of Arestor. Argus had a hundred eyes round his head, that took their rest two at a time in succession while the others kept watch and stayed on guard. Wherever he stood he was looking at Io, and had Io in front of his eyes when his back was turned. He let her graze in the light, but when the sun sank below the earth, he penned her, and fastened a rope round her innocent neck. She grazed on the leaves of trees and bitter herbs. She often lay on the bare ground, and the poor thing drank water from muddy streams. When she wished to stretch her arms out to Argus in supplication, she had no arms to stretch. Trying to complain, a lowing came from her mouth, and she was alarmed and frightened by the sound of her own voice. When she came to Inachus’ riverbanks where she often used to play and saw her gaping mouth and her new horns in the water, she grew frightened and fled terrified of herself.

Inachus finds Io and grieves for her

The naiads160 did not know her: Inachus himself did not know her, but she followed her father, followed her sisters, allowing herself to be petted, and offering herself to be admired. Old Inachus pulled some grasses and held them out to her: she licked her father’s hand and kissed his palm, could not hold back her tears, and if only words could have come she would have begged for help, telling her name and her distress. With letters drawn in the dust with her hoof, instead of words, she traced the sad story of her changed form. ‘Pity me!’ said her father Inachus, clinging to the groaning heifer’s horns and snow-white neck, ‘Pity me!’ he sighed; ‘Are you really my daughter I searched the wide world for? There was less sadness with you lost than found! Without speech, you do not answer in words to mine, only heave deep sighs from your breast, and all you can do is low in reply to me. Unknowingly I was arranging marriage and a marriage-bed for you, hoping for a son-in-law first and then grandchildren. Now you must find a mate from the herd, and from the herd get you a son. I am not allowed by dying to end such sorrow; it is hard to be a god, the door of death closed to me, my grief goes on immortal forever.’ As he mourned, Argus with his star-like eyes drove her to distant pastures, dragging her out of her father’s arms. There, sitting at a distance he occupied a high peak of the mountain, where resting he could keep a watch on every side.

Jupiter sends Mercury to kill Argus

Now the king of the gods can no longer stand Io’s great sufferings, and he calls his son, born of the shining Pleiad,161 and orders him to kill Argus. Mercury, quickly puts on his winged sandals, takes his sleep-inducing wand in his divine hand, and sets his cap on his head. Dressed like this the son of Jupiter touches down on the earth from his father’s stronghold. There he takes off his cap, and doffs his wings, only keeping his wand. Taking this, disguised as a shepherd, he drives she-goats, stolen on the way, through solitary lanes, and plays his reed pipe as he goes. Juno’s guard is captivated by this new sound. ‘You there, whoever you are’ Argus calls ‘you could sit here beside me on this rock; there’s no better grass elsewhere for your flock, and you can see that the shade is fine for shepherds.’

The descendant of Atlas sits down, and passes the day in conversation, talking of many things, and playing on his reed pipe, trying to conquer those watching eyes. Argus however fights to overcome gentle sleep, and though he allows some of his eyes to close, the rest stay vigilant. He even asks, since the reed pipe has only just been invented, how it was invented.

Mercury tells the story of Syrinx

So the god explained ‘On Arcadia’s cold mountain slopes among the wood nymphs, the hamadryads, of Mount Nonacris, one was the most celebrated: the nymphs called her Syrinx. She had often escaped from the satyrs chasing her, and from others of the demi-gods that live in shadowy woods and fertile fields. But she followed the worship of the Ortygian goddess in staying virgin. Her dress caught up like Diana she deceives the eye, and could be mistaken for Leto’s daughter, except that her bow is of horn, and the other’s is of gold. Even so she is deceptive. Pan,162 whose head is crowned with a wreath of sharp pine shoots, saw her, coming from Mount Lycaeus, and spoke to her.’ Now Mercury still had to relate what Pan said, and how the nymph, despising his entreaties, ran through the wilds till she came to the calm waters of sandy Ladon; and how when the river stopped her flight she begged her sisters of the stream to change her; and how Pan, when he thought he now had Syrinx, found that instead of the nymph’s body he only held reeds from the marsh; and, while he sighed there, the wind in the reeds, moving, gave out a clear, plaintive sound. Charmed by this new art and its sweet tones the god said ‘This way of communing with you is still left to me’ So unequal lengths of reed, joined together with wax, preserved the girl’s name.

About to tell all this, Cyllenian Mercury saw that every eye had succumbed and their light was lost in sleep. Quickly he stops speaking and deepens their rest, caressing those drowsy eyes with touches of his magic wand. Then straightaway he strikes the nodding head, where it joins the neck, with his curved sword, and sends it bloody down the rocks, staining the steep cliff. Argus, you are overthrown, the light of your many eyes is extinguished, and one dark sleeps under so many eyelids.

Io is returned to human form

Juno took his eyes and set them into the feathers of her own bird, and filled the tail with star-like jewels. Immediately she blazed with anger, and did not hold back from its consequences. She set a terrifying Fury163 in front of the eyes and mind of that ‘slut’ from the Argolis, buried a tormenting restlessness in her breast, and drove her as a fugitive through the world. You, Nile, put an end to her immeasurable suffering. When she reached you, she fell forward onto her knees on the riverbank and turning back her long neck with her face upwards, in the only way she could, looked to the sky, and with groans and tears and sad lowing seemed to reproach Jupiter and beg him to end her troubles. Jupiter threw his arms round his wife’s neck and pleaded for an end to vengeance, saying ‘Do not fear, in future she will never be a source of pain’ and he called the Stygian waters164 to witness his words.

As the goddess grows calmer, Io regains her previous appearance, and becomes what she once was. The rough hair leaves her body, the horns disappear, the great eyes grow smaller, the gaping mouth shrinks, the shoulders and hands return, and the hooves vanish, each hoof changing back into five nails. Nothing of the heifer is left except her whiteness. Able to stand on two feet she raises herself erect and fearing to speak in case she lows like a heifer, timidly attempts long neglected words.

Phaethon’s parentage

Now she is worshipped as a greatly honoured goddess by crowds of linen clad acolytes.165 In due time she bore a son, Epaphus,166 who shared the cities’ temples with his mother, and was believed to have been conceived from mighty Jupiter’s seed. He had a friend, Phaethon, child of the Sun, equal to him in spirit and years, who once boasted proudly that Phoebus167 was his father, and refused to concede the claim, which Inachus’ grandson could not accept. ‘You are mad to believe all your mother says, and you have an inflated image of your father.’ Phaethon reddened but, from shame, repressed his anger, and went to his mother Clymene with Epaphus’ reproof. ‘To sadden you more, mother, I the free, proud, spirit was silent! I am ashamed that such a reproach can be spoken and not answered. But if I am born at all of divine stock, give me some proof of my high birth, and let me claim my divinity!’ So saying he flung his arms round his mother’s neck, entreating her, by his own and her husband Merops’ life, and by his sisters’ marriages, to reveal to him some true sign of his parentage.

Phaethon sets out for the Palace of the Sun

Clymene, moved perhaps by Phaethon’s entreaties or more by anger at the words spoken, stretched both arms out to the sky and looking up at the sun’s glow said ‘By that brightness marked out by glittering rays, that sees us and hears us, I swear to you, my son, that you are the child of the Sun; of that being you see; you are the child of he who governs the world; if I lie, may he himself decline to look on me again, and may this be the last light to reach our eyes! It is no great effort for you yourself to find your father’s house. The place he rises from is near our land. If you have it in mind to do so, go and ask the sun himself!’ Immediately Phaethon, delighted at his mother’s words, imagining the heavens in his mind, darts off and crosses Ethiopia his people’s land, then India, land of those bathed in radiant fire, and with energy reaches the East.

Book 2

The Palace of the Sun

The palace of the Sun towered up with raised columns, bright with glittering gold, and gleaming bronze like fire. Shining ivory crowned the roofs, and the twin doors radiated light from polished silver. The work of art168 was finer than the material: on the doors Mulciber169 had engraved the waters that surround the earth’s centre, the earthly globe, and the overarching sky. The dark blue sea contains the gods, melodious Triton, shifting Proteus,170 Aegaeon171 crushing two huge whales together, his arms across their backs, and Doris with her daughters, some seen swimming, some sitting on rocks drying their sea-green hair, some riding the backs of fish. They are neither all alike, nor all different, just as sisters should be. The land shows men and towns, woods and creatures, rivers and nymphs and other rural gods. Above them was an image of the glowing sky, with six signs of the zodiac on the right hand door and the same number on the left.

As soon as Clymene’s son had climbed the steep path there, and entered the house of this parent of whose relationship to him he was uncertain, he immediately made his way into his father’s presence, but stopped some way off, unable to bear his light too close. Wearing a purple robe, Phoebus sat on a throne shining with bright emeralds. To right and left stood the Day, Month, and Year, the Century and the equally spaced Hours. Young Spring stood there circled with a crown of flowers, naked Summer wore a garland of ears of corn, Autumn was stained by the trodden grapes, and icy Winter had white, bristling hair.

Phaethon and his father

The Sun,172 seated in the middle of them, looked at the boy, who was fearful of the strangeness of it all, with eyes that see everything, and said ‘What reason brings you here? What do you look for on these heights, Phaethon, son that no father need deny?’ Phaethon replied ‘Universal light of the great world, Phoebus, father, if you let me use that name, if Clymene is not hiding some fault behind false pretence, give me proof father, so they will believe I am your true offspring, and take away this uncertainty from my mind!’ He spoke, and his father removed the crown of glittering rays from his head and ordered him to come nearer. Embracing him, he said ‘It is not to be denied you are worthy to be mine, and Clymene has told you the truth of your birth. So that you can banish doubt, ask for any favour, so that I can grant it to you. May the Stygian lake, that my eyes have never seen, by which the gods swear, witness my promise.’ Hardly had he settled back properly in his seat when the boy asked for his father’s chariot and the right to control his wing-footed horses for a day.

The Sun’s admonitions

His father regretted his oath. Three times, and then a fourth, shaking his bright head, he said ‘Your words show mine were rash; if only it were right to retract my promise! I confess my boy I would only refuse you this one thing. It is right to dissuade you. What you want is unsafe. Phaethon you ask too great a favour, and one that is unfitting for your strength and boyish years. Your fate is mortal: it is not mortal what you ask. Unknowingly you aspire to more than the gods can share. Though each deity can please themselves, within what is allowed, no one except myself has the power to occupy the chariot of fire. Even the lord of mighty Olympus, who hurls terrifying lightning-bolts from his right hand, cannot drive this team, and who is greater than Jupiter?’

His further warnings

‘The first part of the track is steep, and one that my fresh horses at dawn can hardly climb. In mid-heaven it is highest, where to look down on earth and sea often alarms even me, and makes my heart tremble with awesome fear. The last part of the track is downwards and needs sure control. Then even Tethys173 herself, who receives me in her submissive waves, is accustomed to fear that I might dive headlong. Moreover the rushing sky is constantly turning, and drags along the remote stars, and whirls them in rapid orbits. I move the opposite way, and its momentum does not overcome me as it does all other things, and I ride contrary to its swift rotation. Suppose you are given the chariot. What will you do? Will you be able to counter the turning poles so that the swiftness of the skies does not carry you away? Perhaps you conceive in imagination that there are groves there and cities of the gods and temples with rich gifts. The way runs through ambush, and apparitions of wild beasts! Even if you keep your course, and do not steer awry, you must still avoid the horns of Taurus the Bull, Sagittarius the Haemonian Archer, raging Leo and the Lion’s jaw, Scorpio’s cruel pincers sweeping out to encircle you from one side, and Cancer’s crab-claws reaching out from the other. You will not easily rule those proud horses, breathing out through mouth and nostrils the fires burning in their chests. They scarcely tolerate my control when their fierce spirits are hot, and their necks resist the reins. Beware my boy, that I am not the source of a gift fatal to you, while something can still be done to set right your request!’

Phaethon insists on driving the chariot

‘No doubt, since you ask for a certain sign to give you confidence in being born of my blood, I give you that sure sign by fearing for you, and show myself a father by fatherly anxiety. Look at me. If only you could look into my heart, and see a father’s concern from within! Finally, look around you, at the riches the world holds, and ask for anything from all of the good things in earth, sea, and sky. I can refuse you nothing. Only this one thing I take exception to, which would truly be a punishment and not an honour. Phaethon, you ask for punishment as your reward! Why do you unknowingly throw your coaxing arms around my neck? Have no doubt! Whatever you ask will be given, I have sworn it by the Stygian streams, but make a wiser choice!’

The warning ended, but Phaethon still rejected his words, and pressed his purpose, blazing with desire to drive the chariot. So, as he had the right, his father led the youth to the high chariot, Vulcan’s work. It had an axle of gold, and a gold chariot pole, wheels with golden rims, and circles of silver spokes. Along the yoke chrysolites and gemstones, set in order, glowed with brilliance reflecting Phoebus’ own light.

The Sun’s instructions

Now while brave Phaethon is gazing in wonder at the workmanship, see, Aurora, awake in the glowing east, opens wide her bright doors, and her rose-filled courts. The stars, whose ranks are shepherded by Lucifer the morning star,174 vanish, and he, last of all, leaves his station in the sky.

When Titan saw his setting, as the earth and skies were reddening, and just as the crescent of the vanishing moon faded, he ordered the swift Hours to yoke his horses. The goddesses quickly obeyed his command, and led the team, sated with ambrosial food and breathing fire, out of the tall stables, and put on their ringing harness. Then the father rubbed his son’s face with a sacred ointment, and made it proof against consuming flames, and placed his rays amongst his hair, and foreseeing tragedy, and fetching up sighs from his troubled heart, said ‘If you can at least obey your father’s promptings, spare the whip, boy, and rein them in more strongly! They run swiftly of their own accord. It is a hard task to check their eagerness. And do not please yourself, taking a path straight through the five zones of heaven! The track runs obliquely in a wide curve, and bounded by the three central regions, avoids the southern pole and the Arctic north. This is your road, you will clearly see my wheel-marks, and so that heaven and earth receive equal warmth, do not sink down too far or heave the chariot into the upper air! Too high and you will scorch the roof of heaven: too low, the earth. The middle way is safest.

‘Nor must you swerve too far right towards writhing [Dragon], nor lead your wheels too far left towards sunken [Altar].175Hold your way between them! I leave the rest to Fortune, I pray she helps you, and takes better care of you than you do yourself. While I have been speaking, dewy night has touched her limit on Hesperus’176 far western shore. We have no time for freedom! We are needed: Aurora, the dawn, shines, and the shadows are gone. Seize the reins in your hand, or if your mind can be changed, take my counsel, do not take my horses! While you can, while you still stand on solid ground, before unknowingly you take to the chariot you have unluckily chosen, let me light the world, while you watch in safety!

The Horses run wild

The boy has already taken possession of the fleet chariot, and stands proudly, and joyfully, takes the light reins in his hands, and thanks his unwilling father.

Meanwhile the sun’s swift horses, Pyroïs, Eoüs, Aethon, and the fourth, Phlegon, fill the air with fiery whinnying, and strike the bars with their hooves. When Tethys, ignorant of her grandson’s fate, pushed back the gate, and gave them access to the wide heavens, rushing out, they tore through the mists in the way with their hooves and, lifted by their wings, overtook the East winds rising from the same region. But the weight was lighter than the horses of the Sun could feel, and the yoke was free of its accustomed load. Just as curved-sided boats rock in the waves without their proper ballast, and being too light are unstable at sea, so the chariot, free of its usual burden, leaps in the air and rushes into the heights as though it were empty.

As soon as they feel this the team of four run wild and leave the beaten track, no longer running in their pre-ordained course. He was terrified, unable to handle the reins entrusted to him, not knowing where the track was, nor, if he had known, how to control the team. Then for the first time the chill stars of the Great and Little Bears, grew hot, and tried in vain to douse themselves in forbidden waters. And the Dragon, Draco, that is nearest to the frozen pole, never formidable before and sluggish with the cold, now glowed with heat, and took to seething with new fury. They say that you Bootës also fled in confusion, slow as you are and hampered by the Plough.

Phaethon lets go of the reins

When the unlucky Phaethon looked down from the heights of the sky at the earth far, far below he grew pale and his knees quaked with sudden fear, and his eyes were robbed of shadow by the excess light. Now he would rather he had never touched his father’s horses, and regrets knowing his true parentage and possessing what he asked for. Now he wants only to be called Merops’ son, as he is driven along like a ship in a northern gale, whose master lets go the ropes, and leaves her to prayer and the gods. What can he do? Much of the sky is now behind his back, but more is before his eyes. Measuring both in his mind, he looks ahead to the west he is not fated to reach and at times back to the east. Dazed he is ignorant how to act, and can neither grasp the reins nor has the power to loose them, nor can he change course by calling the horses by name. Also, alarmed, he sees the marvellous forms of huge creatures everywhere in the glowing sky. There is a place where Scorpio bends his pincers in twin arcs, and, with his tail and his curving arms stretched out to both sides, spreads his body and limbs over two star signs. When the boy saw this monster drenched with black and poisonous venom threatening to wound him with its arched sting, robbed of his wits by chilling horror, he dropped the reins.

The mountains burn

When the horses feel the reins lying across their backs, after he has thrown them down, they veer off course and run unchecked through unknown regions of the air. Wherever their momentum takes them there they run, lawlessly, striking against the fixed stars in deep space and hurrying the chariot along remote tracks. Now they climb to the heights of heaven, now rush headlong down its precipitous slope, sweeping a course nearer to the earth. The Moon, amazed, sees her brother’s horses running below her own, and the boiling clouds smoke. The earth bursts into flame, in the highest regions first, opens in deep fissures and all its moisture dries up. The meadows turn white, the trees are consumed with all their leaves, and the scorched corn makes its own destruction. But I am bemoaning the lesser things. Great cities are destroyed with all their walls, and the flames reduce whole nations with all their peoples to ashes. The woodlands burn, with the hills. Mount Athos is on fire, Cilician Taurus, Tmolus, Oete and Ida, dry now once covered with fountains, and Helicon home of the Muses, and Haemus not yet linked with King Oeagrius’ name. Etna blazes with immense redoubled flames, the twin peaks of Parnassus, Eryx, Cynthus, Othrys, Rhodope fated at last to lose its snow, Mimas and Dindyma, Mycale and Cithaeron, ancient in rites. Its chilly climate cannot save Scythia. The Caucasus burn, and Ossa along with Pindus, and Olympos greater than either, and the lofty Alps and cloud-capped Apennines.

The rivers are dried up

Then, truly, Phaethon sees the whole earth on fire. He cannot bear the violent heat, and he breathes the air as if from a deep furnace. He feels his chariot glowing white. He can no longer stand the ash and sparks flung out, and is enveloped in dense, hot smoke. He does not know where he is, or where he is going, swept along by the will of the winged horses.

It was then, so they believe, that the Ethiopians acquired their dark colour, since the blood was drawn to the surface of their bodies. Then Libya became a desert, the heat drying up her moisture. Then the nymphs with dishevelled hair wept bitterly for their lakes and fountains. Boeotia searches for Dirce’s rills, Argos for Amymone’s fountain, Corinth for the Pirenian spring. Nor are the rivers safe because of their wide banks. The Don turns to steam in mid-water, and old Peneus, and Mysian Caicus and swift-flowing Ismenus, Arcadian Erymanthus, Xanthus destined to burn again, golden Lycormas and Maeander playing in its watery curves, Thracian Melas and Laconian Eurotas. Babylonian Euphrates burns. Orontes burns and quick Thermodon, Ganges, Phasis, and Danube. Alpheus boils. Spercheos’ banks are on fire. The gold that the River Tagus carries is molten with the fires, and the swans for whose singing Maeonia’s riverbanks are famous, are scorched in Caÿster’s midst. The Nile fled in terror to the ends of the earth, and hid its head that remains hidden. Its seven mouths are empty and dust-filled, seven channels without a stream.

The same fate parches the Thracian rivers, Hebrus and Strymon, and the western rivers, Rhine, Rhone, Po and the Tiber who had been promised universal power. Everywhere the ground breaks apart, light penetrates through the cracks down into Tartarus, and terrifies the king of the underworld and his queen. The sea contracts and what was a moment ago wide sea is a parched expanse of sand. Mountains emerge from the water, and add to the scattered Cyclades. The fish dive deep, and the dolphins no longer dare to rise arcing above the water, as they have done, into the air. The lifeless bodies of seals float face upwards on the deep. They even say that Nereus himself, and Doris and her daughters drifted through warm caves.177 Three times Neptune tried to lift his fierce face and arms above the waters. Three times he could not endure the burning air.

Earth complains

Nevertheless, kindly Earth, surrounded as she was by sea, between the open waters and the dwindling streams that had buried themselves in their mother’s dark womb, lifted her smothered face. Putting her hand to her brow, and shaking everything with her mighty tremors, she sank back a little lower than she used to be, and spoke in a faint voice ‘If this pleases you, if I have deserved it, O king of the gods, why delay your lightning bolts? If it is right for me to die through the power of fire, let me die by your fire and let the doer of it lessen the pain of the deed! I can hardly open my lips to say these words’ (the heat was choking her). Look at my scorched hair and the ashes in my eyes, the ashes over my face! Is this the honour and reward you give me for my fruitfulness and service, for carrying wounds from the curved plough and the hoe, for being worked throughout the year, providing herbage and tender grazing for the flocks, produce for the human race and incense to minister to you gods?

Even if you find me deserving of ruin, what have the waves done, why does your brother deserve this? Why are the waters that were his share by lot diminished and so much further from the sky? If neither regard for me or for your brother moves you pity at least your own heavens! Look around you on either side: both the poles are steam-ing! If the fire should melt them, your own palace will fall! Atlas himself is suffering, and can barely hold up the white-hot sky on his shoulders! If the sea and the land and the kingdom of the heavens are destroyed, we are lost in ancient chaos! Save whatever is left from the flames, and think of our common interest!

Jupiter intervenes and Phaethon dies

So the Earth spoke, and unable to tolerate the heat any longer or speak any further, she withdrew her face into her depths closer to the caverns of the dead. But the all-powerful father of the gods climbs to the highest summit of heaven, from where he spreads his clouds over the wide earth, from where he moves the thunder and hurls his quivering lightning bolts, calling on the gods, especially on him who had handed over the sun chariot, to witness that, unless he himself helps, the whole world will be overtaken by a ruinous fate. Now he has no clouds to cover the earth, or rain to shower from the sky. He thundered, and balancing a lightning bolt in his right hand threw it from eye-level at the charioteer, removing him, at the same moment, from the chariot and from life, extinguishing fire with fierce fire. Thrown into confusion the horses, lurching in different directions, wrench their necks from the yoke and throw off the broken harness. Here the reins lie, there the axle torn from the pole, there the spokes of shattered wheels, and the fragments of the wrecked chariot are flung far and wide.

But Phaethon, flames ravaging his glowing hair, is hurled headlong, leaving a long trail in the air, as sometimes a star does in the clear sky, appearing to fall although it does not fall. Far from his own country, in a distant part of the world, the river god Eridanus takes him from the air, and bathes his smoke-blackened face. There the Italian nymphs consign his body, still smoking from that triple-forked flame, to the earth, and they also carve a verse in the rock:

HERE PHAETHON LIES WHO THE SUN’S JOURNEY MADE

DARED ALL THOUGH HE BY WEAKNESS WAS BETRAYED

Phaethon’s sisters grieve for him

Now the father, pitiful, ill with grief, hid his face, and, if we can believe it, a whole day went by without the sun. But the fires gave light, so there was something beneficial amongst all that evil. But Clymene, having uttered whatever can be uttered at such misfortune, grieving and frantic and tearing her breast, wandered over the whole earth first looking for her son’s limbs, and then failing that his bones. She found his bones already buried however, beside the riverbank in a foreign country. Falling to the ground she bathed with tears the name she could read on the cold stone and warmed it against her naked breast. The Heliads, her daughters and the Sun’s, cry no less, and offer their empty tribute of tears to the dead, and, beating their breasts with their hands, they call for their brother night and day, and lie down on his tomb, though he cannot hear their pitiful sighs.

The sisters turned into poplar trees

Four times the moon had joined her crescent horns to form her bright disc. They by habit, since use creates habit, devoted themselves to mourning. Then Phaethüsa, the eldest sister, when she tried to throw herself to the ground, complained that her ankles had stiffened, and when radiant Lampetia tried to come near her she was suddenly rooted to the spot. A third sister attempting to tear at her hair pulled out leaves. One cried out in pain that her legs were sheathed in wood, another that her arms had become long branches. While they wondered at this, bark closed round their thighs and by degrees over their waists, breasts, shoulders, and hands, and all that was left free were their mouths calling for their mother. What can their mother do but go here and there as the impulse takes her, pressing her lips to theirs where she can? It is no good. She tries to pull the bark from their bodies and break off new branches with her hands, but drops of blood are left behind like wounds. ‘Stop, mother, please’ cries out whichever one she hurts, ‘Please stop: It is my body in the tree you are tearing. Now, farewell.’ and the bark closed over her with her last words. Their tears still flow, and hardened by the sun, fall as amber from the virgin branches, to be taken by the bright river and sent onwards to adorn Roman brides.

Cycnus

Cycnus,178 the son of Sthenelus witnessed this marvel, who though he was kin to you Phaethon, through his mother, was closer still in love. Now, though he had ruled the people and great cities of Liguria, he left his kingdom, and filled Eridanus’ green banks and streams, and the woods the sisters had become part of, with his grief. As he did so his voice vanished and white feathers hid his hair, his long neck stretched out from his body, his reddened fingers became webbed, wings covered his sides, and a rounded beak his mouth. So Cycnus became a new kind of bird, the swan. But he had no faith in Jupiter and the heavens, remembering the lightning bolt the god in his severity had hurled. He looked for standing water, and open lakes hating fire, choosing to live in floods rather than flames.

The Sun returns to his task

Meanwhile Phaethon’s father, mourning and without his accustomed brightness, as if in eclipse, hated the light, himself and the day. He gave his mind over to grief, and to grief added his anger, and refused to provide his service to the earth. ‘Enough’ he says ‘since the beginning my task has given me no rest and I am weary of work without end and labour without honour! Whoever chooses to can steer the chariot of light! If no one does, and all the gods acknowledge they cannot, let Jupiter himself do it, so that for a while at least, while he tries to take the reins, he must put aside the lightning bolts that leave fathers bereft! Then he will know when he has tried the strength of those horses, with hooves of fire, that the one who failed to rule them well did not deserve to be killed.’

All the gods gather round Sol,179 as he talks like this, and beg him not to shroud everything with darkness. Jupiter himself tries to excuse the fire he hurled, adding threats to his entreaties as kings do. Then Phoebus rounds up his horses, maddened and still trembling with terror, and in pain lashes out at them with goad and whip (really lashes out) reproaching them and blaming them for his son’s death.

Jupiter sees Callisto

Now the all-powerful father of the gods circuits the vast walls of heaven and examines them to check if anything has been loosened by the violent fires. When he sees they are as solid and robust as ever he inspects the earth and the works of humankind. Arcadia above all is his greatest care. He restores her fountains and streams, that are still hardly daring to flow, gives grass to the bare earth, leaves to the trees, and makes the scorched forests grow green again.

Often, as he came and went, he would stop short at the sight of a girl from Nonacris, feeling the fire take in the very marrow of his bones. She was not one to spin soft wool or play with her hair. A clasp fastened her tunic, and a white ribbon held back her loose tresses. Dressed like this, with a spear or a bow in her hand, she was one of Diana’s180 companions. No nymph who roamed Maenalus was dearer to Trivia,181 goddess of the crossways, than she, Callisto, was. But no favour lasts long.

Jupiter rapes Callisto

The sun was high, just path the zenith, when she entered a grove that had been untouched through the years. Here she took her quiver from her shoulder, unstrung her curved bow, and lay down on the grass, her head resting on her painted quiver. Jupiter, seeing her there weary and unprotected, said ‘Here, surely, my wife will not see my cunning, or if she does find out it is, oh it is, worth a quarrel! Quickly he took on the face and dress of Diana, and said ‘Oh, girl who follows me, where in my domains have you been hunting?’

The virgin girl got up from the turf replying ‘Greetings, goddess greater than Jupiter: I say it even though he himself hears it.’ He did hear, and laughed, happy to be judged greater than himself, and gave her kisses unrestrainedly, and not those that virgins give. When she started to say which woods she had hunted he embraced and prevented her and not without committing a crime. Face to face with him, as far as a woman could, (I wish you had seen her Juno: you would have been kinder to her) she fought him, but how could a girl win, and who is more powerful than Jove? Victorious, Jupiter made for the furthest reaches of the sky: while to Callisto the grove was odious and the wood seemed knowing. As she retraced her steps she almost forgot her quiver and its arrows, and the bow she had left hanging.

Diana discovers Callisto’s shame

Behold how Diana, with her band of huntresses, approaching from the heights of Maenalus, magnificent from the kill, spies her there, and seeing her calls out. At the shout she runs, afraid at first in case it is Jupiter disguised, but when she sees the other nymphs come forward she realises there is no trickery and joins their number. Alas! How hard it is not to show one’s guilt in one’s face! She can scarcely lift her eyes from the ground, not as she used to be, wedded to her goddess’ side or first of the whole company, but is silent and by her blushing shows signs of her shame at being attacked. Even if she were not herself virgin, Diana could sense her guilt in a thousand ways. They say all the nymphs could feel it.

Nine crescent moons had since grown full when the goddess faint from the chase in her brother’s hot sunlight found a cool grove out of which a murmuring stream ran, winding over fine sand. She loved the place and tested the water with her foot. Pleased with this too she said ‘Any witness is far away, let’s bathe our bodies naked in the flowing water.’ The Arcadian girl blushed: all of them took off their clothes: one of them tried to delay: hesitantly the tunic was removed and there her shame was revealed with her naked body. Terrified she tried to conceal her swollen belly. Diana cried ‘Go, far away from here: do not pollute the sacred fountain!’ and the Moon-goddess commanded her to leave her band of followers.

Callisto turned into a bear

The great Thunderer’s wife had known about all this for a long time and had held back her severe punishment until the proper time. Now there was no reason to wait. The girl had given birth to a boy, Arcas, and that in itself enraged Juno. When she turned her angry eyes and mind to thought of him she cried out ‘Nothing more was needed, you adulteress, than your fertility, and your marking the insult to me by giving birth, making public my Jupiter’s crime. You’ll not carry this off safely. Now, insolent girl, I will take that shape away from you, that pleased you and my husband so much!’ At this she clutched her in front by the hair of her forehead and pulled her face forwards onto the ground. Callisto stretched out her arms for mercy: those arms began to bristle with coarse black hairs: her hands arched over and changed into curved claws to serve as feet: and her face, that Jupiter had once praised, was disfigured by gaping jaws: and so that her prayers and words of entreaty might not attract him her power of speech was taken from her. An angry, threatening growl, harsh and terrifying, came from her throat. Still her former feelings remained intact though she was now a bear. She showed her misery in continual groaning, raising such hands as she had left to the starry sky, feeling, though she could not speak it, Jupiter’s indifference. Ah, how often she wandered near the house and fields that had once been her home, not daring to sleep in the lonely woods! Ah, how often she was driven among the rocks by the baying hounds, and the huntress fled in fear from the hunters! Often she hid at the sight of wild beasts forgetting what she was, and though a bear she shuddered at the sight of other bears on the mountains and feared the wolves though her father Lycaon182 ran with them.

Arcas and Callisto become constellations

And now Arcas, grandson of Lycaon, had reached his fifteenth year ignorant of his parentage. While he was hunting wild animals, while he was finding suitable glades and penning up the Erymanthian groves with woven nets, he came across his mother, who stood still at sight of Arcas and appeared to know him. He shrank back from those unmoving eyes gazing at him so fixedly, uncertain what made him afraid, and when she quickly came nearer he was about to pierce her chest with his lethal spear. All-powerful Jupiter restrained him and in the same moment removed them and the possibility of that wrong, and together, caught up through the void on the winds, he set them in the heavens and made them similar constellations, the Great and Little Bear.

Juno complains to Tethys and Oceanus

Juno was angered when she saw his inamorato shining among the stars, and went down into the waters to white-haired Tethys and old Oceanus to whom the gods often make reverence. When they asked her the reason for her visit she began ‘You ask me why I, the queen of the gods, have left my home in the heavens to be here? Another has taken my place in the sky! I tell a lie, if you do not see, when night falls and the world darkens, newly exalted stars to wound me, set in the sky, where the remotest and shortest orbit circles the uttermost pole. Why should anyone wish to avoid wounding Juno or dread my enmity if I only benefit those I harm? Oh what a great achievement! Oh what marvellous powers I have! I stopped her being human and she becomes a goddess! This is the punishment I inflict on the guilty! This is my wonderful sovereignty! Let him take away her animal form and restore her former beauty as he did before with that Argive girl, Io. Why not divorce Juno, install her in my place, and let Lycaon be his father-in-law? If this contemptible insult to your foster-child moves you, shut out the seven stars of the Bear from your dark blue waters, repulse this constellation set in the heavens as a reward for her defilement, and do not let my rival dip in your pure flood!’

The Raven and the Crow

The gods of the sea nodded their consent. Then Juno, in her light chariot drawn by painted peacocks, drove up through the clear air. These peacocks had only recently been painted, when Argus was killed, at the same time that your wings, Corvus, croaking Raven, were suddenly changed to black, though they were white before. He was once a bird with silver-white plumage, equal to the spotless doves, not inferior to the geese, those saviours of the Capitol with their watchful cries, or the swan, the lover of rivers. His speech condemned him. Because of his ready speech he, who was once snow white, was now white’s opposite.

Coronis of Larissa was the loveliest girl in all Thessaly. Certainly she pleased you, god of Delphi.183 Well, as long as she was faithful, or not caught out. But that bird of Apolo discovered her adultery and, merciless informer, flew straight to his master to reveal the secret crime. The garrulous Crow followed with flapping wings, wanting to know everything, but when he heard the reason, he said ‘This journey will do you no good: don’t ignore my prophecy! See what I was, see what I am, and search out the justice in it. Truth was my downfall.

Once upon a time Pallas184 hid a child, Erichthonius, born without a human mother, in a box made of [Athenian] osiers.185 She gave this to the three virgin daughters of two-natured Cecrops,186 who was part human part serpent, and ordered them not to pry into its secret. Hidden in the light leaves that grew thickly over an elm-tree I set out to watch what they might do. Two of the girls, Pandrosus and Herse, obeyed without cheating, but the third Aglauros called her sisters cowards and undid the knots with her hand, and inside they found a baby boy with a snake stretched out next to him. That act I betrayed to the goddess. And this is the reward I got for it, no longer consecrated to Minerva’s protection, and ranked below the Owl, that night-bird! My punishment should be a warning to all birds not to take risks by speaking out.

The Crow’s story