Shahnameh

Shahnmeh

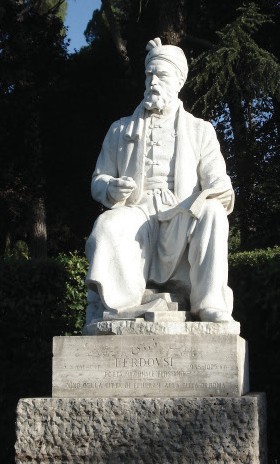

Abu’l-Qasim Ferdowsi (ca. 935-ca. 1020 C.E.)

Begun ca. 977 and finished 1010 C.E. Iran

Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, is an epic that includes other material, stretching from the creation of the world, through the legendary heroes that are the protagonists of epic literature, to the historical kings of Persia (modern-day Iran) up to the Muslim invasion. Written in classical Persian, with very few Arabic words, the Shahnameh records the history of Persia at a time when its traditions were changing. The characters in the epic follow Zoroastrianism, the state religion of Persia from at least 1000 B.C.E. (and perhaps as early as 1500 B.C.E.) until the Muslim invasion in 650 C.E. Zoroastrianism is monotheistic; the one god is Ahura Mazda (also called Hormozd in the text), who is challenged by an evil spirit named Angra Mainyu (also called Ahriman in the text). In the story of “Sekander” (Alexander the Great), Ferdowsi rewrites history, making Alexander the (secret) son of a Persian king, so that his conquest of the Persian Empire is an internal struggle, rather than a Persian defeat by an outside invader. In “Rudabeh,” the meeting of Rudabeh and her true love includes the earliest written reference to a Rapunzel-like scene in literature. The other selection is from the story of Rostam and his son Sohrab, one of the most famous and frequently translated sections in the epic because of its subject matter: a father and son who unknowingly end up on opposite sides on a battlefield.

Written by Laura J. Getty

“The Shah nameh from Persian literature, volume 1

Firdusi, translated by James Atkinson

License: Public Domain

“Rúdábeh

The chief of Kábul was descended from the family of Zohák. He was named Mihráb, and to secure the safety of his state, paid annual tribute to Sám. Mihráb, on the arrival of Zál, went out of the city to see him, and was hospitably entertained by the young hero, who soon discovered that he had a daughter of wonderful attractions.

Her name Rúdábeh; screened from public view,

Her countenance is brilliant as the sun;

From head to foot her lovely form is fair

As polished ivory. Like the spring, her cheek

Presents a radiant bloom,—in stature tall,

And o’er her silvery brightness, richly flow

Dark musky ringlets clustering to her feet.

She blushes like the rich pomegranate flower;

Her eyes are soft and sweet as the narcissus,

Her lashes from the raven’s jetty plume

Have stolen their blackness, and her brows are bent

Like archer’s bow. Ask ye to see the moon?

Look at her face. Seek ye for musky fragrance?

She is all sweetness. Her long fingers seem

Pencils of silver, and so beautiful

Her presence, that she breathes of Heaven and love.

Such was the description of Rúdábeh, which inspired the heart of Zál with the most violent affection, and imagination added to her charms.

Mihráb again waited on Zál, who received him graciously, and asked him in what manner he could promote his wishes. Mihráb said that he only desired him to become his guest at a banquet he intended to invite him to; but Zál thought proper to refuse, because he well knew, if he accepted an invitation of the kind from a relation of Zohák, that his father Sám and the King of Persia would be offended. Mihráb returned to Kábul disappointed, and having gone into his harem, his wife, Síndokht, inquired after the stranger from Zábul, the white-headed son of Sám. She wished to know what he was like, in form and feature, and what account he gave of his sojourn with the Símúrgh. Mihráb described him in the warmest terms of admiration—he was valiant, he said, accomplished and handsome, with no other defect than that of white hair. And so boundless was his praise, that Rúdábeh, who was present, drank every word with avidity, and felt her own heart warmed into admiration and love. Full of emotion, she afterwards said privately to her attendants:

“To you alone the secret of my heart

I now unfold; to you alone confess

The deep sensations of my captive soul.

I love, I love; all day and night of him

I think alone—I see him in my dreams—

You only know my secret—aid me now,

And soothe the sorrows of my bursting heart.”

The attendants were startled with this confession and entreaty and ventured to remonstrate against so preposterous an attachment.

“What! hast thou lost all sense of shame,

All value for thy honored name!

That thou, in loveliness supreme,

Of every tongue the constant theme,

Should choose, and on another’s word.

The nursling of a Mountain Bird!

A being never seen before,

Which human mother never bore!

And can the hoary locks of age,

A youthful heart like thine engage?

Must thy enchanting form be prest

To such a dubious monster’s breast?

And all thy beauty’s rich array,

Thy peerless charms be thrown away?”

This violent remonstrance was more calculated to rouse the indignation of Rúdábeh than to induce her to change her mind. It did so. But she subdued her resentment, and again dwelt upon the ardor of her passion.

“My attachment is fixed, my election is made,

And when hearts are enchained ‘tis in vain to upbraid.

Neither Kízar nor Faghfúr I wish to behold,

Nor the monarch of Persia with jewels and gold;

All, all I despise, save the choice of my heart,

And from his beloved image I never can part.

Call him aged, or young, ‘tis a fruitless endeavour

To uproot a desire I must cherish for ever;

Call him old, call him young, who can passion control?

Ever present, and loved, he entrances my soul.

‘Tis for him I exist—him I worship alone,

And my heart it must bleed till I call him my own.”

As soon as the attendants found that Rúdábeh’s attachment was deeply fixed, and not to be removed, they changed their purpose, and became obedient to her wishes, anxious to pursue any measure that might bring Zál and their mistress together. Rúdábeh was delighted with this proof of their regard.

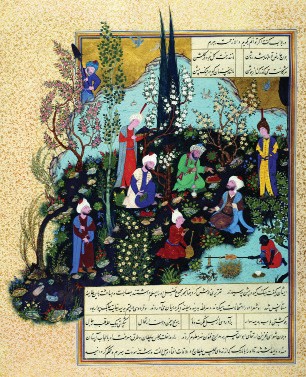

It was spring-time, and the attendants repaired towards the halting-place of Zál, in the neighborhood of the city. Their occupation seemed to be gathering roses along the romantic banks of a pellucid streamlet, and when they purposely strayed opposite the tent of Zál, he observed them, and asked his friends—why they presumed to gather roses in his garden. He was told that they were damsels sent by the moon of Kábulistán from the palace of Mihráb to gather roses, and upon hearing this his heart was touched with emotion. He rose up and rambled about for amusement, keeping the direction of the river, followed by a servant with a bow. He was not far from the damsels, when a bird sprung up from the water, which he shot, upon the wing, with an arrow. The bird happened to fall near the rose-gatherers, and Zál ordered his servant to bring it to him. The attendants of Rúdábeh lost not the opportunity, as he approached them, to inquire who the archer was. “Know ye not,” answered the servant, “that this is Ním-rúz, the son of Sám, and also called Dustán, the greatest warrior ever known.” At this the damsels smiled, and said that they too belonged to a person of distinction—and not of inferior worth—to a star in the palace of Mihráb. “We have come from Kábul to the King of Zábulistán, and should Zál and Rúdábeh be of equal rank, her ruby lips may become acquainted with his, and their wished-for union be effected.” When the servant returned, Zál was immediately informed of the conversation that had taken place, and in consequence presents were prepared.

They who to gather roses came—went back

With precious gems—and honorary robes;

And two bright finger-rings were secretly

Sent to the princess.

Then did the attendants of Rúdábeh exult in the success of their artifice, and say that the lion had come into their toils. Rúdábeh herself, however, had some fears on the subject. She anxiously sought to know exactly the personal appearance of Zál, and happily her warmest hopes were realized by the description she received. But one difficulty remained—how were they to meet? How was she to see with her own eyes the man whom her fancy had depicted in such glowing colors? Her attendants, sufficiently expert at intrigue, soon contrived the means of gratifying her wishes. There was a beautiful rural retreat in a sequestered situation, the apartments of which were adorned with pictures of great men, and ornamented in the most splendid manner. To this favorite place Rúdábeh retired, and most magnificently dressed, awaiting the coming of Zál, whom her attendants had previously invited to repair thither as soon as the sun had gone down. The shadows of evening were falling as he approached, and the enamoured princess thus addressed him from her balcony:—

“May happiness attend thee ever, thou,

Whose lucid features make this gloomy night

Clear as the day; whose perfume scents the breeze;

Thou who, regardless of fatigue, hast come

On foot too, thus to see me—”

Hearing a sweet voice, he looked up, and beheld a bright face in the balcony, and he said to the beautiful vision:

“How often have I hoped that Heaven

Would, in some secret place display

Thy charms to me, and thou hast given

My heart the wish of many a day;

For now thy gentle voice I hear,

And now I see thee—speak again!

Speak freely in a willing ear,

And every wish thou hast obtain.”

Not a word was lost upon Rúdábeh, and she soon accomplished her object. Her hair was so luxuriant, and of such a length, that casting it loose it flowed down from the balcony; and, after fastening the upper part to a ring, she requested Zál to take hold of the other end and mount up. He ardently kissed the musky tresses, and by them quickly ascended.

Then hand in hand within the chambers they

Gracefully passed.—Attractive was the scene,

The walls embellished by the painter’s skill,

And every object exquisitely formed,

Sculpture, and architectural ornament,

Fit for a king. Zál with amazement gazed

Upon what art had done, but more he gazed

Upon the witching radiance of his love,

Upon her tulip cheeks, her musky locks,

Breathing the sweetness of a summer garden;

Upon the sparkling brightness of her rings,

Necklace, and bracelets, glittering on her arms.

His mien too was majestic—on his head

He wore a ruby crown, and near his breast

Was seen a belted dagger. Fondly she

With side-long glances marked his noble aspect,

The fine proportions of his graceful limbs,

His strength and beauty. Her enamoured heart

Suffused her cheek with blushes, every glance

Increased the ardent transports of her soul.

So mild was his demeanour, he appeared

A gentle lion toying with his prey.

Long they remained rapt in admiration

Of each other. At length the warrior rose,

And thus addressed her: “It becomes not us

To be forgetful of the path of prudence,

Though love would dictate a more ardent course,

How oft has Sám, my father, counselled me,

Against unseeming thoughts,—unseemly deeds,—

Always to choose the right, and shun the wrong.

How will he burn with anger when he hears

This new adventure; how will Minúchihr

Indignantly reproach me for this dream!

This waking dream of rapture! but I call

High Heaven to witness what I now declare—

Whoever may oppose my sacred vows,

I still am thine, affianced thine, for ever.”

And thus Rúdábeh: “Thou hast won my heart,

And kings may sue in vain; to thee devoted,

Thou art alone my warrior and my love.”

Thus they exclaimed,—then Zál with fond adieus

Softly descended from the balcony, And hastened to his tent.

As speedily as possible he assembled together his counsellors and Múbids to obtain their advice on the present extraordinary occasion, and he represented to them the sacred importance of encouraging matrimonial alliances.

For marriage is a contract sealed by Heaven—

How happy is the Warrior’s lot, amidst

His smiling children; when he dies, his son

Succeeds him, and enjoys his rank and name.

And is it not a glorious thing to say—

This is the son of Zál, or this of Sám,

The heir of his renowned progenitor?

He then related to them the story of his love and affection for the daughter of Mihráb; but the Múbids, well knowing that the chief of Kábul was of the family of Zohák, the serpent-king, did not approve the union desired, which excited the indignation of Zál. They, however, recommended his writing a letter to Sám, who might, if he thought proper, refer the matter to Minúchihr. The letter was accordingly written and despatched, and when Sám received it, he immediately referred the question to his astrologers, to know whether the nuptials, if solemnized between Zál and Rúdábeh, would be prosperous or not. They foretold that the nuptials would be prosperous, and that the issue would be a son of wonderful strength and power, the conqueror of the world. This announcement delighted the heart of the old warrior, and he sent the messenger back with the assurance of his approbation of the proposed union, but requested that the subject might be kept concealed till he returned with his army from the expedition to Karugsár, and was able to consult with Minúchihr.

Zál, exulting at his success, communicated the glad tidings to Rúdábeh by their female emissary, who had hitherto carried on successfully the correspondence between them. But as she was conveying an answer to this welcome news, and some presents to Zál, Síndokht, the mother of Rúdábeh, detected her, and, examining the contents of the packet, she found sufficient evidence, she thought, of something wrong.

“What treachery is this? What have we here!

Sirbund and male attire? Thou, wretch, confess!

Disclose thy secret doings.”

The emissary, however, betrayed nothing; but declared that she was a dealer in jewels and dresses, and had been only showing her merchandise to Rúdábeh. Síndokht, in extreme agitation of mind, hastened to her daughter’s apartment to ascertain the particulars of this affair, when Rúdábeh at once fearlessly acknowledged her unalterable affection for Zál,

“I love him so devotedly, all day,

All night my tears have flowed unceasingly;

And one hair of his head I prize more dearly

Than all the world beside; for him I live;

And we have met, and we have sat together,

And pledged our mutual love with mutual joy

And innocence of heart.”

Rúdábeh further informed her of Sám’s consent to their nuptials, which in some degree satisfied the mother.

But when Mihráb was made acquainted with the arrangement, his rage was unbounded, for he dreaded the resentment of Sám and Minúchihr when the circumstances became fully known to them. Trembling with indignation he drew his dagger, and would have instantly rushed to Rúdábeh’s chamber to destroy her, had not Síndokht fallen at his feet and restrained him. He insisted, however, on her being brought before him; and upon his promise not to do her any harm, Síndokht complied. Rúdábeh disdained to take off her ornaments to appear as an offender and a supplicant, but, proud of her choice, went into her father’s presence, gayly adorned with jewels, and in splendid apparel. Mihráb received her with surprise.

“Why all this glittering finery? Is the devil

United to an angel? When a snake

Is met with in Arabia, it is killed!”

But Rúdábeh answered not a word, and was permitted to retire with her mother.

When Minúchihr was apprised of the proceedings between Zál and Rúdábeh, he was deeply concerned, anticipating nothing but confusion and ruin to Persia from the united influence of Zál and Mihráb. Feridún had purified the world from the abominations of Zohák, and as Mihráb was a descendant of that merciless tyrant, he feared that some attempt would be made to resume the enormities of former times; Sám was therefore required to give his advice on the occasion.

The conqueror of Karugsár and Mázinderán was received on his return with cordial rejoicings, and he charmed the king with the story of his triumphant success. The monarch against whom he had fought was descended, on the mother’s side, from Zohák, and his Demon army was more numerous than ants, or clouds of locusts, covering mountain and plain. Sám thus proceeded in his description of the conflict.

“And when he heard my voice, and saw what deeds

I had performed, approaching me, he threw

His noose; but downward bending I escaped,

And with my bow I showered upon his head

Steel-pointed arrows, piercing through the brain;

Then did I grasp his loins, and from his horse

Cast him upon the ground, deprived of life.

At this, the demons terrified and pale,

Shrunk back, some flying to the mountain wilds,

And others, taken on the battle-field,

Became obedient to the Persian king.”

Minúchihr, gratified by this result of the expedition, appointed Sám to a new enterprise, which was to destroy Kábul by fire and sword, especially the house of Mihráb; and that ruler, of the serpent-race, and all his adherents were to be put to death. Sám, before he took leave to return to his own government at Zábul, tried to dissuade him from this violent exercise of revenge, but without making any sensible impression upon him.

Meanwhile the vindictive intentions of Minúchihr, which were soon known at Kábul, produced the greatest alarm and consternation in the family of Mihráb. Zál now returned to his father, and Sám sent a letter to Minúchihr, again to deprecate his wrath, and appointed Zál the messenger. In this letter Sám enumerates his services at Karugsár and Mázinderán, and especially dwells upon the destruction of a prodigious dragon.

“I am thy servant, and twice sixty years

Have seen my prowess. Mounted on my steed,

Wielding my battle-axe, overthrowing heroes,

Who equals Sám, the warrior? I destroyed

The mighty monster, whose devouring jaws

Unpeopled half the land, and spread dismay

From town to town. The world was full of horror,

No bird was seen in air, no beast of prey

In plain or forest; from the stream he drew

The crocodile; the eagle from the sky.

The country had no habitant alive,

And when I found no human being left,

I cast away all fear, and girt my loins,

And in the name of God went boldly forth,

Armed for the strife. I saw him towering rise,

Huge as a mountain, with his hideous hair

Dragging upon the ground; his long black tongue

Shut up the path; his eyes two lakes of blood;

And, seeing me, so horrible his roar,

The earth shook with affright, and from his mouth

A flood of poison issued. Like a lion

Forward I sprang, and in a moment drove

A diamond-pointed arrow through his tongue,

Fixing him to the ground. Another went

Down his deep throat, and dreadfully he writhed.

A third passed through his middle. Then I raised

My battle-axe, cow-headed, and with one

Tremendous blow, dislodged his venomous brain,

And deluged all around with blood and poison.

There lay the monster dead, and soon the world

Regained its peace and comfort. Now I’m old,

The vigour of my youth is past and gone,

And it becomes me to resign my station,

To Zál, my gallant son.”

Mihráb continued in such extreme agitation, that in his own mind he saw no means of avoiding the threatened desolation of his country but by putting his wife and daughter to death. Síndokht however had a better resource, and suggested the expediency of waiting upon Sám herself, to induce him to forward her own views and the nuptials between Zál and Rúdábeh. To this Mihráb assented, and she proceeded, mounted on a richly caparisoned horse, to Zábul with most magnificent presents, consisting of three hundred thousand dínars; ten horses with golden, and thirty with silver, housings; sixty richly attired damsels, carrying golden trays of jewels and musk, and camphor, and wine, and sugar; forty pieces of figured cloth; a hundred milch camels, and a hundred others for burden; two hundred Indian swords, a golden crown and throne, and four elephants. Sám was amazed and embarrassed by the arrival of this splendid array. If he accepted the presents, he would incur the anger of Minúchihr; and if he rejected them, Zál would be disappointed and driven to despair. He at length accepted them, and concurred in the wishes of Síndokht respecting the union of the two lovers.

When Zál arrived at the court of Minúchihr, he was received with honor, and the letter of Sám being read, the king was prevailed upon to consent to the pacific proposals that were made in favor of Mihráb, and the nuptials. He too consulted his astrologers, and was informed that the offspring of Zál and Rúdábeh would be a hero of matchless strength and valor. Zál, on his return through Kábul, had an interview with Rúdábeh, who welcomed him in the most rapturous terms:—

Be thou for ever blest, for I adore thee,

And make the dust of thy fair feet my pillow.

In short, with the approbation of all parties the marriage at length took place, and was celebrated at the beautiful summer-house where first the lovers met. Sám was present at Kábul on the happy occasion, and soon afterwards returned to Sístán, preparatory to resuming his martial labors in Karugsár and Mázinderán.

As the time drew near that Rúdábeh should become a mother, she suffered extremely from constant indisposition, and both Zál and Síndokht were in the deepest distress on account of her precarious state.

The cypress leaf was withering; pale she lay,

Unsoothed by rest or sleep, death seemed approaching.

At last Zál recollected the feather of the Símúrgh, and followed the instructions which he had received, by placing it on the fire. In a moment darkness surrounded them, which was, however, immediately dispersed by the sudden appearance of the Símúrgh. “Why,” said the Símúrgh, “do I see all this grief and sorrow? Why are the teardrops in the warrior’s eyes? A child will be born of mighty power, who will become the wonder of the world.”

The Símúrgh then gave some advice which was implicitly attended to, and the result was that Rúdábeh was soon out of danger. Never was beheld so prodigious a child. The father and mother were equally amazed. They called the boy Rustem. On the first day he looked a year old, and he required the milk of ten nurses. A likeness of him was immediately worked in silk, representing him upon a horse, and armed like a warrior, which was sent to Sám, who was then fighting in Mázinderán, and it made the old champion almost delirious with joy. At Kábul and Zábul there was nothing but feasting and rejoicing, as soon as the tidings were known, and thousands of dínars were given away in charity to the poor. When Rustem was five years of age, he ate as much as a man, and some say that even in his third year he rode on horseback. In his eighth year he was as powerful as any hero of the time.

In beauty of form and in vigour of limb,

No mortal was ever seen equal to him.

Both Sám and Mihráb, though far distant from the scene of felicity, were equally anxious to proceed to Zábulistán to behold their wonderful grandson. Both set off, but Mihráb arrived first with great pomp, and a whole army for his suite, and went forth with Zál to meet Sám, and give him an honorable welcome. The boy Rustem was mounted on an elephant, wearing a splendid crown, and wanted to join them, but his father kindly prevented him undergoing the inconvenience of alighting. Zál and Mihráb dismounted as soon as Sám was seen at a distance, and performed the ceremonies of an affectionate reception. Sám was indeed amazed when he did see the boy, and showered blessings on his head.

Afterwards Sám placed Mihráb on his right hand, and Zál on his left, and Rustem before him, and began to converse with his grandson, who thus manifested to him his martial disposition.

“Thou art the champion of the world, and I

The branch of that fair tree of which thou art

The glorious root: to thee I am devoted,

But ease and leisure have no charms for me;

Nor music, nor the songs of festive joy.

Mounted and armed, a helmet on my brow,

A javelin in my grasp, I long to meet

The foe, and cast his severed head before thee.”

Then Sám made a royal feast, and every apartment in his palace was richly decorated, and resounded with mirth and rejoicing. Mihráb was the merriest, and drank the most, and in his cups saw nothing but himself, so vain had he become from the countenance he had received. He kept saying:—

“Now I feel no alarm about Sám or Zál-zer,

Nor the splendour and power of the great Minúchihr;

Whilst aided by Rustem, his sword, and his mace,

Not a cloud of misfortune can shadow my face.

All the laws of Zohák I will quickly restore,

And the world shall be fragrant and blest as before.”

This exultation plainly betrayed the disposition of his race; and though Sám smiled at the extravagance of Mihráb, he looked up towards Heaven, and prayed that Rustem might not prove a tyrant, but be continually active in doing good, and humble before God.

Upon Sám departing, on his return to Karugsár and Mázinderán, Zál went with Rustem to Sístán, a province dependent on his government, and settled him there. The white elephant, belonging to Minúchihr, was kept at Sístán. One night Rustem was awakened out of his sleep by a great noise, and cries of distress when starting up and inquiring the cause, he was told that the white elephant had got loose, and was trampling and crushing the people to death. In a moment he issued from his apartment, brandishing his mace; but was soon stopped by the servants, who were anxious to expostulate with him against venturing out in the darkness of night to encounter a ferocious elephant. Impatient at being thus interrupted he knocked down one of the watchmen, who fell dead at his feet, and the others running away, he broke the lock of the gate, and escaped. He immediately opposed himself to the enormous animal, which looked like a mountain, and kept roaring like the River Nil. Regarding him with a cautious and steady eye, he gave a loud shout, and fearlessly struck him a blow, with such strength and vigor, that the iron mace was bent almost double. The elephant trembled, and soon fell exhausted and lifeless in the dust. When it was communicated to Zál that Rustem had killed the animal with one blow, he was amazed, and fervently returned thanks to heaven. He called him to him, and kissed him, and said: “My darling boy, thou art indeed unequalled in valor and magnanimity.”

Then it occurred to Zál that Rustem, after such an achievement, would be a proper person to take vengeance on the enemies of his grandfather Narímán, who was sent by Feridún with a large army against an enchanted fort situated upon the mountain Sipund, and who whilst endeavoring to effect his object, was killed by a piece of rock thrown down from above by the besieged. The fort, which was many miles high, inclosed beautiful lawns of the freshest verdure, and delightful gardens abounding with fruit and flowers; it was also full of treasure. Sám, on hearing of the fate of his father, was deeply afflicted, and in a short time proceeded against the fort himself; but he was surrounded by a trackless desert. He knew not what course to pursue; not a being was ever seen to enter or come out of the gates, and, after spending months and years in fruitless endeavors, he was compelled to retire from the appalling enterprise in despair. “Now,” said Zál to Rustem, “the time is come, and the remedy is at hand; thou art yet unknown, and may easily accomplish our purpose.” Rustem agreed to the proposed adventure, and according to his father’s advice, assumed the dress and character of a salt-merchant, prepared a caravan of camels, and secreted arms for himself and companions among the loads of salt. Everything being ready they set off, and it was not long before they reached the fort on the mountain Sipund. Salt being a precious article, and much wanted, as soon as the garrison knew that it was for sale, the gates were opened; and then was Rustem seen, together with his warriors, surrounded by men, women, and children, anxiously making their purchases, some giving clothes in exchange, some gold, and some silver, without fear or suspicion.

But when the night came on, and it was dark,

Rustem impatient drew his warriors forth,

And moved towards the mansion of the chief—

But not unheard. The unaccustomed noise,

Announcing warlike menace and attack,

Awoke the Kotwál, who sprung up to meet

The peril threatened by the invading foe.

Rustem meanwhile uplifts his ponderous mace,

And cleaves his head, and scatters on the ground

The reeking brains. And now the garrison

Are on the alert, all hastening to the spot

Where battle rages; midst the deepened gloom

Flash sparkling swords, which show the crimson earth

Bright as the ruby.

Rustem continued fighting with the people of the fort all night, and just as morning dawned, he discovered the chief and slew him. Those who survived, then escaped, and not one of the inhabitants remained within the walls alive. Rustem’s next object was to enter the governor’s mansion. It was built of stone, and the gate, which was made of iron, he burst open with his battle-axe, and advancing onward, he discovered a temple, constructed with infinite skill and science, beyond the power of mortal man, and which contained amazing wealth, in jewels and gold. All the warriors gathered for themselves as much treasure as they could carry away, and more than imagination can conceive; and Rustem wrote to Zál to know his further commands on the subject of the capture. Zál, overjoyed at the result of the enterprise, replied:

Thou hast illumed the soul of Narímán,

Now in the blissful bowers of Paradise,

By punishing his foes with fire and sword.

He then recommended him to load all the camels with as much of the invaluable property as could be removed, and bring it away, and then burn and destroy the whole place, leaving not a single vestige; and the command having been strictly complied with, Rustem retraced his steps to Zábulistán.

On his return Zál pressed him to his heart,

And paid him public honors. The fond mother

Kissed and embraced her darling son, and all

Uniting, showered their blessings on his head.

Story of Sohráb

O ye, who dwell in Youth’s inviting bowers,

Waste not, in useless joy, your fleeting hours,

But rather let the tears of sorrow roll,

And sad reflection fill the conscious soul.

For many a jocund spring has passed away, 5

And many a flower has blossomed, to decay;

And human life, still hastening to a close,

Finds in the worthless dust its last repose.

Still the vain world abounds in strife and hate,

And sire and son provoke each other’s fate; 10

And kindred blood by kindred hands is shed,

And vengeance sleeps not—dies not, with the dead.

All nature fades—the garden’s treasures fall,

Young bud, and citron ripe—all perish, all.

And now a tale of sorrow must be told, 15

A tale of tears, derived from Múbid old,

And thus remembered.—

With the dawn of day,

Rustem arose, and wandering took his way,

Armed for the chase, where sloping to the sky, 20

Túrán’s lone wilds in sullen grandeur lie;

There, to dispel his melancholy mood,

He urged his matchless steed through glen and wood.

Flushed with the noble game which met his view,

He starts the wild-ass o’er the glistening dew; 25

And, oft exulting, sees his quivering dart,

Plunge through the glossy skin, and pierce the heart.

Tired of the sport, at length, he sought the shade,

Which near a stream embowering trees displayed,

And with his arrow’s point, a fire he raised, 30

And thorns and grass before him quickly blazed.

The severed parts upon a bough he cast,

To catch the flames; and when the rich repast

Was drest; with flesh and marrow, savory food,

He quelled his hunger; and the sparkling flood 35

That murmured at his feet, his thirst represt;

Then gentle sleep composed his limbs to rest.

Meanwhile his horse, for speed and form renown’d,

Ranged o’er the plain with flowery herbage crown’d,

Encumbering arms no more his sides opprest, 40

No folding mail confined his ample chest,

Gallant and free, he left the Champion’s side,

And cropp’d the mead, or sought the cooling tide;

When lo! it chanced amid that woodland chase,

A band of horsemen, rambling near the place, 45

Saw, with surprise, superior game astray,

And rushed at once to seize the noble prey;

But, in the imminent struggle, two beneath

His steel-clad hoofs received the stroke of death;

One proved a sterner fate—for downward borne, 50

The mangled head was from the shoulders torn.

Still undismayed, again they nimbly sprung,

And round his neck the noose entangling flung:

Now, all in vain, he spurns the smoking ground,

In vain the tumult echoes all around; 55

They bear him off, and view, with ardent eyes,

His matchless beauty and majestic size;

Then soothe his fury, anxious to obtain,

A bounding steed of his immortal strain.

When Rustem woke, and miss’d his favourite horse, 60

The loved companion of his glorious course;

Sorrowing he rose, and, hastening thence, began

To shape his dubious way to Samengán;

“Reduced to journey thus, alone!” he said,

“How pierce the gloom which thickens round my head; 65

Burthen’d, on foot, a dreary waste in view,

Where shall I bend my steps, what path pursue?

The scoffing Turks will cry, ‘Behold our might!

We won the trophy from the Champion-knight!

From him who, reckless of his fame and pride, 70

Thus idly slept, and thus ignobly died,’”

Girding his loins he gathered from the field,

His quivered stores, his beamy sword and shield,

Harness and saddle-gear were o’er him slung.

Bridle and mail across his shoulders hung. 75

Then looking round, with anxious eye, to meet,

The broad impression of his charger’s feet,

The track he hail’d, and following, onward prest.

While grief and hope alternate filled his breast.

O’er vale and wild-wood led, he soon descries. 80

The regal city’s shining turrets rise.

And when the Champion’s near approach is known,

The usual homage waits him to the throne.

The king, on foot, received his welcome guest

With preferred friendship, and his coming blest: 85

But Rustem frowned, and with resentment fired,

Spoke of his wrongs, the plundered steed required.

“I’ve traced his footsteps to your royal town,

Here must he be, protected by your crown;

But if retained, if not from fetters freed, 90

My vengeance shall o’ertake the felon-deed.”

“My honored guest!” the wondering King replied—

“Shall Rustem’s wants or wishes be denied?

But let not anger, headlong, fierce, and blind,

O’ercloud the virtues of a generous mind. 95

If still within the limits of my reign,

The well known courser shall be thine again:

For Rakush never can remain concealed,

No more than Rustem in the battle-field!

Then cease to nourish useless rage, and share 100

With joyous heart my hospitable fare.”

The son of Zál now felt his wrath subdued,

And glad sensations in his soul renewed.

The ready herald by the King’s command,

Convened the Chiefs and Warriors of the land; 105

And soon the banquet social glee restored,

And China wine-cups glittered on the board;

And cheerful song, and music’s magic power,

And sparkling wine, beguiled the festive hour.

The dulcet draughts o’er Rustem’s senses stole, 110

And melting strains absorbed his softened soul.

But when approached the period of repose,

All, prompt and mindful, from the banquet rose;

A couch was spread well worthy such a guest,

Perfumed with rose and musk; and whilst at rest, 115

In deep sound sleep, the wearied Champion lay,

Forgot were all the sorrows of the way.

One watch had passed, and still sweet slumber shed

Its magic power around the hero’s head—

When forth Tahmíneh came—a damsel held 120

An amber taper, which the gloom dispelled,

And near his pillow stood; in beauty bright,

The monarch’s daughter struck his wondering sight.

Clear as the moon, in glowing charms arrayed,

Her winning eyes the light of heaven displayed; 125

Her cypress form entranced the gazer’s view,

Her waving curls, the heart, resistless, drew,

Her eye-brows like the Archer’s bended bow;

Her ringlets, snares; her cheek, the rose’s glow,

Mixed with the lily—from her ear-tips hung 130

Rings rich and glittering, star-like; and her tongue,

And lips, all sugared sweetness—pearls the while

Sparkled within a mouth formed to beguile.

Her presence dimmed the stars, and breathing round

Fragrance and joy, she scarcely touched the ground, 135

So light her step, so graceful—every part

Perfect, and suited to her spotless heart.

Rustem, surprised, the gentle maid addressed,

And asked what lovely stranger broke his rest.

“What is thy name,” he said—“what dost thou seek 140

Amidst the gloom of night? Fair vision, speak!”

“O thou,” she softly sigh’d, “of matchless fame!

With pity hear, Tahmíneh is my name!

The pangs of love my anxious heart employ,

And flattering promise long-expected joy; 145

No curious eye has yet these features seen,

My voice unheard, beyond the sacred screen.

How often have I listened with amaze,

To thy great deeds, enamoured of thy praise;

How oft from every tongue I’ve heard the strain, 150

And thought of thee—and sighed, and sighed again.

The ravenous eagle, hovering o’er his prey,

Starts at thy gleaming sword and flies away:

Thou art the slayer of the Demon brood,

And the fierce monsters of the echoing wood. 155

Where’er thy mace is seen, shrink back the bold,

Thy javelin’s flash all tremble to behold.

Enchanted with the stories of thy fame,

My fluttering heart responded to thy name;

And whilst their magic influence I felt, 160

In prayer for thee devotedly I knelt;

And fervent vowed, thus powerful glory charms,

No other spouse should bless my longing arms.

Indulgent heaven propitious to my prayer,

Now brings thee hither to reward my care. 165

Túrán’s dominions thou hast sought, alone,

By night, in darkness—thou, the mighty one!

O claim my hand, and grant my soul’s desire;

Ask me in marriage of my royal sire;

Perhaps a boy our wedded love may crown, 170

Whose strength like thine may gain the world’s renown.

Nay more—for Samengán will keep my word—

Rakush to thee again shall be restored.”

The damsel thus her ardent thought expressed,

And Rustem’s heart beat joyous in his breast, 175

Hearing her passion—not a word was lost,

And Rakush safe, by him still valued most;

He called her near; with graceful step she came,

And marked with throbbing pulse his kindled flame.

And now a Múbid, from the Champion-knight, 180

Requests the royal sanction to the rite;

O’erjoyed, the King the honoured suit approves,

O’erjoyed to bless the doting child he loves,

And happier still, in showering smiles around,

To be allied to warrior so renowned. 185

When the delighted father, doubly blest,

Resigned his daughter to his glorious guest,

The people shared the gladness which it gave,

The union of the beauteous and the brave.

To grace their nuptial day—both old and young, 190

The hymeneal gratulations sung:

“May this young moon bring happiness and joy,

And every source of enmity destroy.”

The marriage-bower received the happy pair,

And love and transport shower’d their blessings 195

Ere from his lofty sphere the morn had thrown

His glittering radiance, and in splendour shone,

The mindful Champion, from his sinewy arm,

His bracelet drew, the soul-ennobling charm;

And, as he held the wondrous gift with pride, 200

He thus address’d his love-devoted bride!

“Take this,” he said, “and if, by gracious heaven,

A daughter for thy solace should be given,

Let it among her ringlets be displayed,

And joy and honour will await the maid; 205

But should kind fate increase the nuptial-joy,

And make thee mother of a blooming boy,

Around his arm this magic bracelet bind,

To fire with virtuous deeds his ripening mind;

The strength of Sám will nerve his manly form, 210

In temper mild, in valour like the storm;

His not the dastard fate to shrink, or turn

From where the lions of the battle burn;

To him the soaring eagle from the sky

Will stoop, the bravest yield to him, or fly; 215

Thus shall his bright career imperious claim

The well-won honours of immortal fame!”

Ardent he said, and kissed her eyes and face,

And lingering held her in a fond embrace.

When the bright sun his radiant brow displayed, 220

And earth in all its loveliest hues arrayed,

The Champion rose to leave his spouse’s side,

The warm affections of his weeping bride.

For her, too soon the winged moments flew,

Too soon, alas! the parting hour she knew; 225

Clasped in his arms, with many a streaming tear,

She tried, in vain, to win his deafen’d ear;

Still tried, ah fruitless struggle! to impart,

The swelling anguish of her bursting heart.

The father now with gratulations due 230

Rustem approaches, and displays to view

The fiery war-horse—welcome as the light

Of heaven, to one immersed in deepest night;

The Champion, wild with joy, fits on the rein,

And girds the saddle on his back again; 235

Then mounts, and leaving sire and wife behind,

Onward to Sístán rushes like the wind.

But when returned to Zábul’s friendly shade,

None knew what joys the Warrior had delayed;

Still, fond remembrance, with endearing thought, 240

Oft to his mind the scene of rapture brought.

When nine slow-circling months had roll’d away,

Sweet-smiling pleasure hailed the brightening day—

A wondrous boy Tahmíneh’s tears supprest,

And lull’d the sorrows of her heart to rest; 245

To him, predestined to be great and brave,

The name Sohráb his tender mother gave;

And as he grew, amazed, the gathering throng,

View’d his large limbs, his sinews firm and strong;

His infant years no soft endearment claimed: 250

Athletic sports his eager soul inflamed;

Broad at the chest and taper round the loins,

Where to the rising hip the body joins;

Hunter and wrestler; and so great his speed,

He could overtake, and hold the swiftest steed. 255

His noble aspect, and majestic grace,

Betrayed the offspring of a glorious race.

How, with a mother’s ever anxious love,

Still to retain him near her heart she strove!

For when the father’s fond inquiry came, 260

Cautious, she still concealed his birth and name,

And feign’d a daughter born, the evil fraught

With misery to avert—but vain the thought;

Not many years had passed, with downy flight,

Ere he, Tahmíneh’s wonder and delight, 265

With glistening eye, and youthful ardour warm,

Filled her foreboding bosom with alarm.

“O now relieve my heart!” he said, “declare,

From whom I sprang and breathe the vital air.

Since, from my childhood I have ever been, 270

Amidst my play-mates of superior mien;

Should friend or foe demand my father’s name,

Let not my silence testify my shame!

If still concealed, you falter, still delay,

A mother’s blood shall wash the crime away.” 275

“This wrath forego,” the mother answering cried,

“And joyful hear to whom thou art allied.

A glorious line precedes thy destined birth,

The mightiest heroes of the sons of earth.

The deeds of Sám remotest realms admire, 280

And Zál, and Rustem thy illustrious sire!”

In private, then, she Rustem’s letter placed

Before his view, and brought with eager haste

Three sparkling rubies, wedges three of gold,

From Persia sent—“Behold,” she said, “behold 285

Thy father’s gifts, will these thy doubts remove

The costly pledges of paternal love!

Behold this bracelet charm, of sovereign power

To baffle fate in danger’s awful hour;

But thou must still the perilous secret keep, 290

Nor ask the harvest of renown to reap;

For when, by this peculiar signet known,

Thy glorious father shall demand his son,

Doomed from her only joy in life to part,

O think what pangs will rend thy mother’s heart!— 295

Seek not the fame which only teems with woe;

Afrásiyáb is Rustem’s deadliest foe!

And if by him discovered, him I dread,

Revenge will fail upon thy guiltless head.”

The youth replied: “In vain thy sighs and tears, 300

The secret breathes and mocks thy idle fears.

No human power can fate’s decrees control,

Or check the kindled ardour of my soul.

Then why from me the bursting truth conceal?

My father’s foes even now my vengeance feel; 305

Even now in wrath my native legions rise,

And sounds of desolation strike the skies;

Káús himself, hurled from his ivory throne,

Shall yield to Rustem the imperial crown,

And thou, my mother, still in triumph seen, 310

Of lovely Persia hailed the honoured queen!

Then shall Túrán unite beneath my hand,

And drive this proud oppressor from the land!

Father and Son, in virtuous league combined,

No savage despot shall enslave mankind; 315

When Sun and Moon o’er heaven refulgent blaze,

Shall little stars obtrude their feeble rays?”

He paused, and then: “O mother, I must now

My father seek, and see his lofty brow;

Be mine a horse, such as a prince demands, 320

Fit for the dusty field, a warrior’s hands;

Strong as an elephant his form should be,

And chested like the stag, in motion free,

And swift as bird, or fish; it would disgrace

A warrior bold on foot to show his face.” 325

The mother, seeing how his heart was bent,

His day-star rising in the firmament,

Commands the stables to be searched to find

Among the steeds one suited to his mind;

Pressing their backs he tries their strength and nerve, 330

Bent double to the ground their bellies curve;

Not one, from neighbouring plain and mountain brought,

Equals the wish with which his soul is fraught;

Fruitless on every side he anxious turns,

Fruitless, his brain with wild impatience burns, 335

But when at length they bring the destined steed,

From Rakush bred, of lightning’s winged speed,

Fleet, as the arrow from the bow-string flies,

Fleet, as the eagle darting through the skies,

Rejoiced he springs, and, with a nimble bound, 340

Vaults in his seat, and wheels the courser round;

“With such a horse—thus mounted, what remains?

Káús, the Persian King, no longer reigns!”

High flushed he speaks—with youthful pride elate,

Eager to crush the Monarch’s glittering state; 345

He grasps his javelin with a hero’s might,

And pants with ardour for the field of fight.

Soon o’er the realm his fame expanding spread,

And gathering thousands hasten’d to his aid.

His Grand-sire, pleased, beheld the warrior-train 350

Successive throng and darken all the plain;

And bounteously his treasures he supplied,

Camels, and steeds, and gold.—In martial pride,

Sohráb was seen—a Grecian helmet graced

His brow—and costliest mail his limbs embraced. 355

Afrásiyáb now hears with ardent joy,

The bold ambition of the warrior-boy,

Of him who, perfumed with the milky breath

Of infancy, was threatening war and death,

And bursting sudden from his mother’s side, 360

Had launched his bark upon the perilous tide.

The insidious King sees well the tempting hour,

Favouring his arms against the Persian power,

And thence, in haste, the enterprise to share,

Twelve thousand veterans selects with care; 365

To Húmán and Bármán the charge consigns,

And thus his force with Samengán combines;

But treacherous first his martial chiefs he prest,

To keep the secret fast within their breast:—

“For this bold youth must not his father know, 370

Each must confront the other as his foe—

Such is my vengeance! With unhallowed rage,

Father and Son shall dreadful battle wage!

Unknown the youth shall Rustem’s force withstand,

And soon o’erwhelm the bulwark of the land. 375

Rustem removed, the Persian throne is ours,

An easy conquest to confederate powers;

And then, secured by some propitious snare,

Sohráb himself our galling bonds shall wear.

Or should the Son by Rustem’s falchion bleed, 380

The father’s horror at that fatal deed,

Will rend his soul, and ‘midst his sacred grief,

Káús in vain will supplicate relief.”

The tutored chiefs advance with speed, and bring

Imperial presents to the future king; 385

In stately pomp the embassy proceeds;

Ten loaded camels, ten unrivalled steeds,

A golden crown, and throne, whose jewels bright

Gleam in the sun, and shed a sparkling light,

A letter too the crafty tyrant sends, 390

And fraudful thus the glorious aim commends.—

“If Persia’s spoils invite thee to the field,

Accept the aid my conquering legions yield;

Led by two Chiefs of valour and renown,

Upon thy head to place the kingly crown.” 395

Elate with promised fame, the youth surveys

The regal vest, the throne’s irradiant blaze,

The golden crown, the steeds, the sumptuous load

Of ten strong camels, craftily bestowed;

Salutes the Chiefs, and views on every side, 400

The lengthening ranks with various arms supplied.

The march begins—the brazen drums resound,

His moving thousands hide the trembling ground;

For Persia’s verdant land he wields the spear,

And blood and havoc mark his groaning rear. 405

To check the Invader’s horror-spreading course,

The barrier-fort opposed unequal force;

That fort whose walls, extending wide, contained

The stay of Persia, men to battle trained.

Soon as Hujír the dusky crowd descried, 410

He on his own presumptuous arm relied,

And left the fort; in mail with shield and spear,

Vaunting he spoke—“What hostile force is here?

What Chieftain dares our war-like realms invade?”

“And who art thou?” Sohráb indignant said, 415

Rushing towards him with undaunted look—

“Hast thou, audacious! nerve and soul to brook

The crocodile in fight, that to the strife

Singly thou comest, reckless of thy life?”

To this the foe replied—“A Turk and I 420

Have never yet been bound in friendly tie;

And soon thy head shall, severed by my sword,

Gladden the sight of Persia’s mighty lord,

While thy torn limbs to vultures shall be given,

Or bleach beneath the parching blast of heaven.” 425

The youthful hero laughing hears the boast,

And now by each continual spears are tost,

Mingling together; like a flood of fire

The boaster meets his adversary’s ire;

The horse on which he rides, with thundering pace, 430

Seems like a mountain moving from its base;

Sternly he seeks the stripling’s loins to wound,

But the lance hurtless drops upon the ground;

Sohráb, advancing, hurls his steady spear

Full on the middle of the vain Hujír, 435

Who staggers in his seat. With proud disdain

The youth now flings him headlong on the plain,

And quick dismounting, on his heaving breast

Triumphant stands, his Khunjer firmly prest,

To strike the head off—but the blow was stayed—Trembling, 440

for life, the craven boaster prayed.

That mercy granted eased his coward mind,

Though, dire disgrace, in captive bonds confined,

And sent to Húmán, who amazed beheld

How soon Sohráb his daring soul had quelled. 445

When Gúrd-afríd, a peerless warrior-dame,

Heard of the conflict, and the hero’s shame,

Groans heaved her breast, and tears of anger flowed,

Her tulip cheek with deeper crimson glowed;

Speedful, in arms magnificent arrayed, 450

A foaming palfrey bore the martial maid;

The burnished mail her tender limbs embraced,

Beneath her helm her clustering locks she placed;

Poised in her hand an iron javelin gleamed,

And o’er the ground its sparkling lustre streamed; 455

Accoutred thus in manly guise, no eye

However piercing could her sex descry;

Now, like a lion, from the fort she bends,

And ‘midst the foe impetuously descends;

Fearless of soul, demands with haughty tone, 460

The bravest chief, for war-like valour known,

To try the chance of fight. In shining arms,

Again Sohráb the glow of battle warms;

With scornful smiles, “Another deer!” he cries,

“Come to my victor-toils, another prize!” 465

The damsel saw his noose insidious spread,

And soon her arrows whizzed around his head;

With steady skill the twanging bow she drew,

And still her pointed darts unerring flew;

For when in forest sports she touched the string, 470

Never escaped even bird upon the wing;

Furious he burned, and high his buckler held,

To ward the storm, by growing force impell’d;

And tilted forward with augmented wrath,

But Gúrd-áfríd aspires to cross his path; 475

Now o’er her back the slacken’d bow resounds;

She grasps her lance, her goaded courser bounds,

Driven on the youth with persevering might—

Unconquer’d courage still prolongs the fight;

The stripling Chief shields off the threaten’d blow, 480

Reins in his steed, then rushes on the foe;

With outstretch’d arm, he bending backwards hung,

And, gathering strength, his pointed javelin flung;

Firm through her girdle belt the weapon went,

And glancing down the polish’d armour rent. 485

Staggering, and stunned by his superior force,

She almost tumbled from her foaming horse,

Yet unsubdued, she cut the spear in two,

And from her side the quivering fragment drew,

Then gain’d her seat, and onward urged her steed, 490

But strong and fleet Sohráb arrests her speed:

Strikes off her helm, and sees—a woman’s face,

Radiant with blushes and commanding grace!

Thus undeceived, in admiration lost,

He cries, “A woman, from the Persian host! 495

If Persian damsels thus in arms engage,

Who shall repel their warrior’s fiercer rage?”

Then from his saddle thong—his noose he drew,

And round her waist the twisted loop he threw—

“Now seek not to escape,” he sharply said, 500

“Such is the fate of war, unthinking maid!

And, as such beauty seldom swells our pride,

Vain thy attempt to cast my toils aside.”

In this extreme, but one resource remained,

Only one remedy her hope sustained— 505

Expert in wiles each siren-art she knew,

And thence exposed her blooming face to view;

Raising her full black orbs, serenely bright,

In all her charms she blazed before his sight;

And thus addressed Sohráb—“O warrior brave, 510

Hear me, and thy imperilled honour save,

These curling tresses seen by either host,

A woman conquered, whence the glorious boast?

Thy startled troops will know, with inward grief,

A woman’s arm resists their towering chief, 515

Better preserve a warrior’s fair renown,

And let our struggle still remain unknown,

For who with wanton folly would expose

A helpless maid, to aggravate her woes;

The fort, the treasure, shall thy toils repay, 520

The chief, and garrison, thy will obey,

And thine the honours of this dreadful day.”

Raptured he gazed, her smiles resistless move

The wildest transports of ungoverned love.

Her face disclosed a paradise to view, 525

Eyes like the fawn, and cheeks of rosy hue—

Thus vanquished, lost, unconscious of her aim,

And only struggling with his amorous flame,

He rode behind, as if compelled by fate,

And heedless saw her gain the castle-gate. 530

Safe with her friends, escaped from brand and spear,

Smiling she stands, as if unknown to fear.

—The father now, with tearful pleasure wild,

Clasps to his heart his fondly-foster’d child;

The crowding warriors round her eager bend, 535

And grateful prayers to favouring heaven ascend.

Now from the walls, she, with majestic air,

Exclaims: “Thou warrior of Túrán! forbear,

Why vex thy soul, and useless strife demand!

Go, and in peace enjoy thy native land.” 540

Stern he rejoins: “Thou beauteous tyrant! say,

Though crown’d with charms, devoted to betray,

When these proud walls, in dust and ruins laid,

Yield no defence, and thou a captive maid,

Will not repentance through thy bosom dart, 545

And sorrow soften that disdainful heart?”

Quick she replied: “O’er Persia’s fertile fields

The savage Turk in vain his falchion wields;

When King Káús this bold invasion hears,

And mighty Rustem clad in arms appears! 550

Destruction wide will glut the slippery plain,

And not one man of all thy host remain.

Alas! that bravery, high as thine, should meet

Amidst such promise, with a sure defeat,

But not a gleam of hope remains for thee, 555

Thy wondrous valour cannot keep thee free.

Avert the fate which o’er thy head impends,

Return, return, and save thy martial friends!”

Thus to be scorned, defrauded of his prey,

With victory in his grasp—to lose the day! 560

Shame and revenge alternate filled his mind;

The suburb-town to pillage he consigned,

And devastation—not a dwelling spared;

The very owl was from her covert scared;

Then thus: “Though luckless in my aim to-day, 565

To-morrow shall behold a sterner fray;

This fort, in ashes, scattered o’er the plain.”

He ceased—and turned towards his troops again;

There, at a distance from the hostile power,

He brooding waits the slaughter-breathing hour. 570

Meanwhile the sire of Gúrd-afríd, who now

Governed the fort, and feared the warrior’s vow;

Mournful and pale, with gathering woes opprest,

His distant Monarch trembling thus addrest.

But first invoked the heavenly power to shed 575

Its choicest blessings o’er his royal head.

“Against our realm with numerous foot and horse,

A stripling warrior holds his ruthless course.

His lion-breast unequalled strength betrays,

And o’er his mien the sun’s effulgence plays: 580

Sohráb his name; like Sám Suwár he shows,

Or Rustem terrible amidst his foes.

The bold Hujír lies vanquished on the plain,

And drags a captive’s ignominious chain;

Myriads of troops besiege our tottering wall, 585

And vain the effort to suspend its fall.

Haste, arm for fight, this Tartar-power withstand,

Let sweeping Vengeance lift her flickering brand;

Rustem alone may stem the roaring wave,

And, prompt as bold, his groaning country save. 590

Meanwhile in flight we place our only trust,

Ere the proud ramparts crumble in the dust.”

Swift flies the messenger through secret ways,

And to the King the dreadful tale conveys,

Then passed, unseen, in night’s concealing shade, 595

The mournful heroes and the warrior maid.

Soon as the sun with vivifying ray,

Gleams o’er the landscape, and renews the day;

The flaming troops the lofty walls surround,

With thundering crash the bursting gates resound. 600

Already are the captives bound, in thought,

And like a herd before the conqueror brought;

Sohráb, terrific o’er the ruin, views

His hopes deceived, but restless still pursues.

An empty fortress mocks his searching eye, 605

No steel-clad chiefs his burning wrath defy;

No warrior-maid reviving passion warms,

And soothes his soul with fondly-valued charms.

Deep in his breast he feels the amorous smart,

And hugs her image closer to his heart. 610

“Alas! that Fate should thus invidious shroud

The moon’s soft radiance in a gloomy cloud;

Should to my eyes such winning grace display,

Then snatch the enchanter of my soul away!

A beauteous roe my toils enclosed in vain, 615

Now I, her victim, drag the captive’s chain;

Strange the effects that from her charms proceed,

I gave the wound, and I afflicted bleed!

Vanquished by her, I mourn the luckless strife;

Dark, dark, and bitter, frowns my morn of life. 620

A fair unknown my tortured bosom rends,

Withers each joy, and every hope suspends.”

Impassioned thus Sohráb in secret sighed,

And sought, in vain, o’er-mastering grief to hide.

Can the heart bleed and throb from day to day, 625

And yet no trace its inmost pangs betray?

Love scorns control, and prompts the labouring sigh,

Pales the red lip, and dims the lucid eye;

His look alarmed the stern Túránian Chief,

Closely he mark’d his heart-corroding grief;— 630

And though he knew not that the martial dame,

Had in his bosom lit the tender flame;

Full well he knew such deep repinings prove,

The hapless thraldom of disastrous love.

Full well he knew some idol’s musky hair, 635

Had to his youthful heart become a snare,

But still unnoted was the gushing tear,

Till haply he had gained his private ear:—

“In ancient times, no hero known to fame,

Not dead to glory e’er indulged the flame; 640

Though beauty’s smiles might charm a fleeting hour,

The heart, unsway’d, repelled their lasting power.

A warrior Chief to trembling love a prey?

What! weep for woman one inglorious day?

Canst thou for love’s effeminate control, 645

Barter the glory of a warrior’s soul?

Although a hundred damsels might be gained,

The hero’s heart shall still be free, unchained.

Thou art our leader, and thy place the field

Where soldiers love to fight with spear and shield; 650

And what hast thou to do with tears and smiles,

The silly victim to a woman’s wiles?

Our progress, mark! from far Túrán we came,

Through seas of blood to gain immortal fame;

And wilt thou now the tempting conquest shun, 655

When our brave arms this Barrier-fort have won?

Why linger here, and trickling sorrows shed,

Till mighty Káús thunders o’er thy head!

Till Tús, and Gíw, and Gúdarz, and Báhrám,

And Rustem brave, Ferámurz, and Rehám, 660

Shall aid the war! A great emprise is thine,

At once, then, every other thought resign;

For know the task which first inspired thy zeal,

Transcends in glory all that love can feel.

Rise, lead the war, prodigious toils require 665

Unyielding strength, and unextinguished fire;

Pursue the triumph with tempestuous rage,

Against the world in glorious strife engage,

And when an empire sinks beneath thy sway

(O quickly may we hail the prosperous day), 670

The fickle sex will then with blooming charms,

Adoring throng to bless thy circling arms!”

Húmán’s warm speech, the spirit-stirring theme,

Awoke Sohráb from his inglorious dream.

No more the tear his faded cheek bedewed, 675

Again ambition all his hopes renewed:

Swell’d his bold heart with unforgotten zeal,

The noble wrath which heroes only feel;

Fiercely he vowed at one tremendous stroke,

To bow the world beneath the tyrant’s yoke! 680

“Afrásiyáb,” he cried, “shall reign alone,

The mighty lord of Persia’s gorgeous throne!”

Burning, himself, to rule this nether sphere,

These welcome tidings charmed the despot’s ear.

Meantime Káús, this dire invasion known, 685

Had called his chiefs around his ivory throne:

There stood Gurgín, and Báhrám, and Gushwád,

And Tús, and Gíw, and Gúdárz, and Ferhád;

To them he read the melancholy tale,

Gust’hem had written of the rising bale; 690

Besought their aid and prudent choice, to form

Some sure defence against the threatening storm.

With one consent they urge the strong request,

To summon Rustem from his rural rest.—

Instant a warrior-delegate they send, 695

And thus the King invites his patriot-friend,

“To thee all praise, whose mighty arm alone,

Preserves the glory of the Persian throne!

Lo! Tartar hordes our happy realms invade;

The tottering state requires thy powerful aid; 700

A youthful Champion leads the ruthless host,

His savage country’s widely-rumoured boast.

The Barrier-fortress sinks beneath his sway,

Hujír is vanquished, ruin tracks his way;

Strong as a raging elephant in fight, 705

No arm but thine can match his furious might.

Mázinderán thy conquering prowess knew;

The Demon-king thy trenchant falchion slew,

The rolling heavens, abash’d with fear, behold

Thy biting sword, thy mace adorned with gold! 710

Fly to the succour of a King distress’d,

Proud of thy love, with thy protection blest.

When o’er the nation dread misfortunes lower,

Thou art the refuge, thou the saving power.

The chiefs assembled claim thy patriot vows, 715

Give to thy glory all that life allows;

And while no whisper breathes the direful tale,

O, let thy Monarch’s anxious prayers prevail.”

Closing the fragrant page o’ercome with dread,

The afflicted King to Gíw, the warrior, said:— 720

“Go, bind the saddle on thy fleetest horse,

Outstrip the tempest in thy rapid course,

To Rustem swift his country’s woes convey,

Too true art thou to linger on the way;

Speed, day and night—and not one instant wait, 725

Whatever hour may bring thee to his gate.”

Followed no pause—to Gíw enough was said,

Nor rest, nor taste of food, his speed delayed.

And when arrived, where Zábul’s bowers exhale

Ambrosial sweets and scent the balmy gale, 730

The sentinel’s loud voice in Rustem’s ear,

Announced a messenger from Persia, near;

The Chief himself amidst his warriors stood,

Dispensing honours to the brave and good,

And soon as Gíw had joined the martial ring, 735

(The sacred envoy of the Persian King),

He, with becoming loyalty inspired,

Asked what the monarch, what the state required;

But Gíw, apart, his secret mission told—

The written page was speedily unrolled. 740

Struck with amazement, Rustem—“Now on earth

A warrior-knight of Sám’s excelling worth?

Whence comes this hero of the prosperous star?

I know no Turk renowned, like him, in war;

He bears the port of Rustem too, ‘tis said, 745

Like Sám, like Narímán, a warrior bred!

He cannot be my son, unknown to me;

Reason forbids the thought—it cannot be!

At Samengán, where once affection smiled,

To me Tahmíneh bore her only child, 750

That was a daughter?” Pondering thus he spoke,

And then aloud—“Why fear the invader’s yoke?

Why trembling shrink, by coward thoughts dismayed,

Must we not all in dust, at length, be laid?

But come, to Nírum’s palace, haste with me, 755

And there partake the feast—from sorrow free;

Breathe, but awhile—ere we our toils renew,

And moisten the parched lip with needful dew.

Let plans of war another day decide,

We soon shall quell this youthful hero’s pride. 760

The force of fire soon flutters and decays

When ocean, swelled by storms, its wrath displays.

What danger threatens! whence the dastard fear!

Rest, and at leisure share a warrior’s cheer.”

In vain the Envoy prest the Monarch’s grief; 765

The matchless prowess of the stripling chief;

How brave Hujír had felt his furious hand;

What thickening woes beset the shuddering land.

But Rustem, still, delayed the parting day,

And mirth and feasting rolled the hours away; 770

Morn following morn beheld the banquet bright,

Music and wine prolonged the genial rite;

Rapt by the witchery of the melting strain,

No thought of Káús touch’d his swimming brain.

The trumpet’s clang, on fragrant breezes borne, 775

Now loud salutes the fifth revolving morn;

The softer tones which charm’d the jocund feast,

And all the noise of revelry, had ceased,

The generous horse, with rich embroidery deckt,

Whose gilded trappings sparkling light reflect, 780

Bears with majestic port the Champion brave,

And high in air the victor-banners wave.

Prompt at the martial call, Zúára leads

His veteran troops from Zábul’s verdant meads.

Ere Rustem had approached his journey’s end, 785

Tús, Gúdarz, Gushwád, met their champion-friend

With customary honours; pleased to bring

The shield of Persia to the anxious King.

But foaming wrath the senseless monarch swayed;

His friendship scorned, his mandate disobeyed, 790

Beneath dark brows o’er-shadowing deep, his eye

Red gleaming shone, like lightning through the sky

And when the warriors met his sullen view,

Frowning revenge, still more enraged he grew:—

Loud to the Envoy thus he fiercely cried:— 795

“Since Rustem has my royal power defied,

Had I a sword, this instant should his head

Roll on the ground; but let him now be led

Hence, and impaled alive.” Astounded Gíw

Shrunk from such treatment of a knight so true; 800

But this resistance added to the flame,

And both were branded with revolt and shame;

Both were condemned, and Tús, the stern decree

Received, to break them on the felon-tree.

Could daring insult, thus deliberate given, 805

Escape the rage of one to frenzy driven?

No, from his side the nerveless Chief was flung,

Bent to the ground. Away the Champion sprung;

Mounted his foaming horse, and looking round—

His boiling wrath thus rapid utterance found:— 810

“Ungrateful King, thy tyrant acts disgrace

The sacred throne, and more, the human race;

Midst clashing swords thy recreant life I saved,

And am I now by Tús contemptuous braved?

On me shall Tús, shall Káús dare to frown? 815

On me, the bulwark of the regal crown?

Wherefore should fear in Rustem’s breast have birth,

Káús, to me, a worthless clod of earth!

Go, and thyself Sohráb’s invasion stay,

Go, seize the plunderers growling o’er their prey! 820

Wherefore to others give the base command?

Go, break him on the tree with thine own hand.

Know, thou hast roused a warrior, great and free,

Who never bends to tyrant Kings like thee!

Was not this untired arm triumphant seen, 825

In Misser, Rúm, Mázinderán, and Chín!

And must I shrink at thy imperious nod!

Slave to no Prince, I only bow to God.

Whatever wrath from thee, proud King! may fall,

For thee I fought, and I deserve it all. 830

The regal sceptre might have graced my hand,

I kept the laws, and scorned supreme command.

When Kai-kobád and Alberz mountain strayed,

I drew him thence, and gave a warrior’s aid;

Placed on his brows the long-contested crown, 835

Worn by his sires, by sacred right his own;

Strong in the cause, my conquering arms prevailed,

Wouldst thou have reign’d had Rustem’s valour failed

When the White Demon raged in battle-fray,

Wouldst thou have lived had Rustem lost the day?” 840

Then to his friends: “Be wise, and shun your fate,

Fly the wide ruin which o’erwhelms the state;

The conqueror comes—the scourge of great and small,

And vultures, following fast, will gorge on all.

Persia no more its injured Chief shall view”— 845

He said, and sternly from the court withdrew.

The warriors now, with sad forebodings wrung,

Torn from that hope to which they proudly clung,

On Gúdarz rest, to soothe with gentle sway,

The frantic King, and Rustem’s wrath allay. 850

With bitter grief they wail misfortune’s shock,

No shepherd now to guard the timorous flock.

Gúdarz at length, with boding cares imprest,

Thus soothed the anger in the royal breast.

“Say, what has Rustem done, that he should be 855

Impaled upon the ignominious tree?

Degrading thought, unworthy to be bred

Within a royal heart, a royal head.

Hast thou forgot when near the Caspian-wave,

Defeat and ruin had appalled the brave, 860

When mighty Rustem struck the dreadful blow,

And nobly freed thee from the savage foe?

Did Demons huge escape his flaming brand?

Their reeking limbs bestrew’d the slippery strand.

Shall he for this resign his vital breath? 865

What! shall the hero’s recompense be death?

But who will dare a threatening step advance,

What earthly power can bear his withering glance?

Should he to Zábul fired with wrongs return,

The plunder’d land will long in sorrow mourn! 870

This direful presage all our warriors feel,

For who can now oppose the invader’s steel;

Thus is it wise thy champion to offend,

To urge to this extreme thy warrior-friend?

Remember, passion ever scorns control, 875

And wisdom’s mild decrees should rule a Monarch’s soul.”

Káús, relenting, heard with anxious ear,

And groundless wrath gave place to shame and fear;

“Go then,” he cried, “his generous aid implore,

And to your King the mighty Chief restore!” 880

When Gúdarz rose, and seized his courser’s rein,

A crowd of heroes followed in his train.

To Rustem, now (respectful homage paid),

The royal prayer he anxious thus conveyed.

“The King, repentant, seeks thy aid again, 885

Grieved to the heart that he has given thee pain;

But though his anger was unjust and strong,

Thy country still is guiltless of the wrong,

And, therefore, why abandoned thus by thee?

Thy help the King himself implores through me.” 890

Rustem rejoined: “Unworthy the pretence,

And scorn and insult all my recompense?

Must I be galled by his capricious mood?

I, who have still his firmest champion stood?

But all is past, to heaven alone resigned, 895

No human cares shall more disturb my mind!”

Then Gúdarz thus (consummate art inspired

His prudent tongue, with all that zeal required);

“When Rustem dreads Sohráb’s resistless power,

Well may inferiors fly the trying hour! 900

The dire suspicion now pervades us all,

Thus, unavenged, shall beauteous Persia fall!

Yet, generous still, avert the lasting shame,

O, still preserve thy country’s glorious fame!

Or wilt thou, deaf to all our fears excite, 905

Forsake thy friends, and shun the pending fight?

And worse, O grief! in thy declining days,

Forfeit the honours of thy country’s praise?”

This artful censure set his soul on fire,

But patriot firmness calm’d his burning ire; 910

And thus he said—“Inured to war’s alarms,

Did ever Rustem shun the din of arms?

Though frowns from Káús I disdain to bear,

My threatened country claims a warrior’s care.”

He ceased, and prudent joined the circling throng, 915

And in the public good forgot the private wrong.

From far the King the generous Champion viewed,

And rising, mildly thus his speech pursued:—

“Since various tempers govern all mankind,

Me, nature fashioned of a froward mind; 920

And what the heavens spontaneously bestow,

Sown by their bounty must for ever grow.

The fit of wrath which burst within me, soon

Shrunk up my heart as thin as the new moon;

Else had I deemed thee still my army’s boast, 925

Source of my regal power, beloved the most,

Unequalled. Every day, remembering thee,

I drain the wine cup, thou art all to me;

I wished thee to perform that lofty part,

Claimed by thy valour, sanctioned by my heart; 930

Hence thy delay my better thoughts supprest,

And boisterous passions revelled in my breast;

But when I saw thee from my Court retire

In wrath, repentance quenched my burning ire.

O, let me now my keen contrition prove, 935

Again enjoy thy fellowship and love:

And while to thee my gratitude is known,

Still be the pride and glory of my throne.”

Rustem, thus answering said:—“Thou art the King,

Source of command, pure honour’s sacred spring; 940

And here I stand to follow thy behest,

Obedient ever—be thy will expressed,

And services required—Old age shall see

My loins still bound in fealty to thee.”

To this the King:—“Rejoice we then to-day, 945

And on the morrow marshal our array.”

The monarch quick commands the feast of joy,