The Thousand and One Nights

First published ca. 879 C.E.

Middle East and India

The Thousand and One Nights is a collection of mostly Middle Eastern and Indian stories, written in Arabic. Within a frame narrative, it contains numerous stories from different cultures in these regions. The first appearance of a physical fragment of The Thousand and One Nights dates from 879 C.E., and the next evidence was mentioned in the 10th century. By the mid-twentieth century, six different forms had been recognized. The French translation in 1704 by Antoine Galland was the first European translation. English translations of the text began in the nineteenth century, and early English translations sanitized parts of the stories. Based on popular oral storytelling traditions, the stories tend to have improvisational, sensuous, and enchanting qualities.

Written by Kyounghye Kwon

Selections from Thousand and one nights

Anonymous, translated by Edward William Lane

License: Public Domain

Introduction

In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful.

Praise be to God, the Beneficent King, the Creator of the universe, who hath raised the heavens without pillars, and spread out the earth as abed; and blessing and peace be on the lord of apostles, our lord and our master Moḥammad, and his Family; blessing and peace, enduring and constant, unto the day of judgment.

To proceed:—The lives of former generations are a lesson to posterity; that a man may review the remarkable events which have happened to others, and be admonished; and may consider the history of people of preceding ages, and of all that hath befallen them, and be restrained. Extolled be the perfection of Him who hath thus ordained the history of former generations to be a lesson to those which follow. Such are the Tales of a Thousand and One Nights, with their romantic stories and their fables.

It is related (but God alone is all-knowing, as well as all-wise, and almighty, and all-bountiful,) that there was, in ancient times, a King of the countries of India and China, possessing numerous troops, and guards, and servants, and domestic dependents: and he had two sons; one of whom was a man of mature age; and the other, a youth. Both of these princes were brave horsemen; but especially the elder, who inherited the kingdom of his father; and governed his subjects with such justice that the inhabitants of his country and whole empire loved him. He was called King Shahriyár: his younger brother was named Sháh-Zemán, and was King of Samarḳand. The administration of their governments was conducted with rectitude, each of them ruling over his subjects with justice during a period of twenty years with the utmost enjoyment and happiness. After this period, the elder King felt a strong desire to see his brother, and ordered his Wezeer to repair to him and bring him.

Having taken the advice of the Wezeer on this subject, he immediately gave orders to prepare handsome presents, such as horses adorned with gold and costly jewels, and memlooks, and beautiful virgins, and expensive stuffs. He then wrote a letter to his brother, expressive of his great desire to see him; and having sealed it, and given it to the Wezeer, together with the presents above mentioned, he ordered the minister to strain his nerves, and tuck up his skirts, and use all expedition in returning. The Wezeer answered, without delay, I hear and obey; and forthwith prepared for the journey: he packed his baggage, removed the burdens, and made ready all his provisions within three days; and on the fourth day, he took leave of the King Shahriyár, and went forth towards the deserts and wastes. He proceeded night and day; and each of the kings under the authority of King Shahriyár by whose residence he passed came forth to meet him, with costly presents, and gifts of gold and silver, and entertained him three days; after which, on the fourth day, he accompanied him one day’s journey, and took leave of him. Thus he continued on his way until he drew near to the city of Samarḳand, when he sent forward a messenger to inform King Sháh-Zemán of his approach. The messenger entered the city, inquired the way to the palace, and, introducing himself to the King, kissed the ground before him, and acquainted him with the approach of his brother’s Wezeer;

upon which Sháh-Zemán ordered the chief officers of his court, and the great men of his kingdom, to go forth a day’s journey to meet him; and they did so; and when they met him, they welcomed him, and walked by his stirrups until they returned to the city. The Wezeer then presented himself before the King Sháh-Zemán, greeted him with a prayer for the divine assistance in his favour, kissed the ground before him, and informed him of his brother’s desire to see him; after which he handed to him the letter. The King took it, read it, and understood its contents; and answered by expressing his readiness to obey the commands of his brother. But, said he (addressing the Wezeer), I will not go until I have entertained thee three days. Accordingly, he lodged him in a palace befitting his rank, accommodated his troops in tents, and appointed them all things requisite in the way of food and drink: and so they remained three days. On the fourth day, he equipped himself for the journey, made ready his baggage, and collected together costly presents suitable to his brother’s dignity.

These preparations being completed, he sent forth his tents and camels and mules and servants and guards, appointed his Wezeer to be governor of the country during his absence, and set out towards his brother’s dominions. At midnight, however, he remembered that he had left in his palace an article which he should have brought with him; and having returned to the palace to fetch it, he there beheld his wife sleeping in his bed, and attended by a male negro slave, who had fallen asleep by her side. On beholding this scene, the world became black before his eyes; and he said within himself, If this is the case when I have not departed from the city, what will be the conduct of this vile woman while I am sojourning with my brother? He then drew his sword, and slew them both in the bed: after which he immediately returned, gave orders for departure, and journeyed to his brother’s capital.

Shahriyár, rejoicing at the tidings of his approach, went forth to meet him, saluted him, and welcomed him with the utmost delight. He then ordered that the city should be decorated on the occasion, and sat down to entertain his brother with cheerful conversation: but the mind of King Sháh-Zemán was distracted by reflections upon the conduct of his wife; excessive grief took possession of him; and his countenance became sallow; and his frame, emaciated. His brother observed his altered condition, and, imagining that it was occasioned by his absence from his dominions, abstained from troubling him or asking respecting the cause, until after the lapse of some days, when at length he said to him, O my brother, I perceive that thy body is emaciated, and thy countenance is become sallow. He answered, O brother, I have an internal sore:—and he informed him not of the conduct of his wife which he had witnessed. Shahriyár then said, I wish that thou wouldest go out with me on a hunting excursion; perhaps thy mind might so be diverted:—but he declined; and Shahriyár went alone to the chase.

Now there were some windows in the King’s palace commanding a view of his garden; and while his brother was looking out from one of these, a door of the palace was opened, and there came forth from it twenty females and twenty male black slaves; and the King’s wife, who was distinguished by extraordinary beauty and elegance, accompanied them to a fountain, where they all disrobed themselves, and sat down together. The King’s wife then called out, O Mes’ood! and immediately a black slave came to her, and embraced her; she doing the like. So also did the other slaves and the women; and all of them continued revelling together until the close of the day. When Sháh-Zemán beheld this spectacle, he said within himself, By Allah! my affliction is lighter than this! His vexation and grief were alleviated, and he no longer abstained from sufficient food and drink.

When his brother returned from his excursion, and they had saluted each other, and King Shahriyár observed his brother Sháh-Zemán, that his colour had returned, that his face had recovered the flush of health, and that he ate with appetite, after his late abstinence, he was surprised, and said, O my brother, when I saw thee last, thy countenance was sallow, and now thy colour hath returned to thee: acquaint me with thy state.—As to the change of my natural complexion, answered Sháh-Zemán, I will inform thee of its cause; but excuse my explaining to thee the return of my colour.—First, said Shahriyár, relate to me the cause of the change of thy proper complexion, and of thy weakness: let me hear it.—Know then, O my brother, he answered, that when thou sentest thy Wezeer to me to invite me to thy presence, I prepared myself for the journey, and when I had gone forth from the city, I remembered that I had left behind me the jewel that I have given thee; I therefore returned to my palace for it, and there I found my wife sleeping in my bed, and attended by a black male slave; and I killed them both, and came to thee: but my mind was occupied by reflections upon this affair, and this was the cause of the change of my complexion, and of my weakness: now, as to the return of my colour, excuse my informing thee of its cause.—But when his brother heard these words, he said, I conjure thee by Allah that thou acquaint me with the cause of the return of thy colour:—so he repeated to him all that he had seen. I would see this, said Shahriyár, with my own eye.—Then, said Sháh-Zemán, give out that thou art going again to the chase, and conceal thyself here with me, and thou shalt witness this conduct, and obtain ocular proof of it.

Shahriyár, upon this, immediately announced that it was his intention to make another excursion. The troops went out of the city with the tents, and the King followed them; and after he had reposed awhile in the camp, he said to his servants, Let no one come in to me:—and he disguised himself, and returned to his brother in the palace, and sat in one of the windows overlooking the garden; and when he had been there a short time, the women and their mistress entered the garden with the black slaves, and did as his brother had described, continuing so until the hour of the afternoon-prayer.

When King Shahriyár beheld this occurrence, reason fled from his head, and he said to his brother Sháh-Zemán, Arise, and let us travel whither we please, and renounce the regal state, until we see whether such a calamity as this have befallen any other person like unto us; and if not, our death will be preferable to our life. His brother agreed to his proposal, and they went out from a private door of the palace, and journeyed continually, days and nights, until they arrived at a tree in the midst of a meadow, by a spring of water, on the shore of the sea. They drank of this spring, and sat down to rest; and when the day had a little advanced, the sea became troubled before them, and there arose from it a black pillar, ascending towards the sky, and approaching the meadow. Struck with fear at the sight, they climbed up into the tree, which was lofty; and thence they gazed to see what this might be: and behold, it was a Jinnee, of gigantic stature, broad-fronted and bulky, bearing on his head a chest. He landed, and came to the tree into which the two Kings had climbed, and, having seated himself beneath it, opened the chest, and took out of it another box, which he also opened; and there came forth from it a young woman, fair and beautiful, like the shining sun. When the Jinnee cast his eyes upon her, he said, O lady of noble race, whom I carried off on thy wedding-night, I have a desire to sleep a little:—and he placed his head upon her knee, and slept. The damsel then raised her head towards the tree, and saw there the two Kings; upon which she removed the head of the Jinnee from her knee, and, having placed it on the ground, stood under the tree, and made signs to the two Kings, as though she would say, Come down, and fear not this ‘Efreet. They answered her, We conjure thee by Allah that thou excuse us in this matter. But she said, I conjure you by the same that ye come down; and if ye do not, I will rouse this ‘Efreet, and he shall put you to a cruel death. So, being afraid, they came down to her; and, after they had remained with her as long as she required, she took from her pocket a purse, and drew out from this a string, upon which were ninety-eight seal-rings; and she said to them, Know ye what are these? They answered, We know not.—The owners of these rings, said she, have, all of them, been admitted to converse with me, like as ye have, unknown to this foolish ‘Efreet; therefore, give me your two rings, ye brothers. So they gave her their two rings from their fingers; and she then said to them, This ‘Efreet carried me off on my wedding-night, and put me in the box, and placed the box in the chest, and affixed to the chest seven locks, and deposited me, thus imprisoned, in the bottom of the roaring sea, beneath the dashing waves; not knowing that, when one of our sex desires to accomplish any object, nothing can prevent her. In accordance with this, says one of the poets:—

Never trust in women; nor rely upon their vows;

For their pleasure and displeasure depend upon their passions.

They offer a false affection; for perfidy lurks within their clothing.

By the tale of Yoosuf be admonished, and guard against their stratagems.

Dost thou not consider that Iblees ejected Adam by means of woman?

And another poet says:—

Abstain from censure; for it will strengthen the censured, and increase desire into violent passion.

If I suffer such passion, my case is but the same as that of many a man before me:

For greatly indeed to be wondered at is he who hath kept himself safe fromwomen’s artifice.

When the two Kings heard these words from her lips, they were struck with the utmost astonishment, and said, one to the other, If this is an ‘Efreet, and a greater calamity hath happened unto him than that which hath befallen us, this is a circumstance that should console us:—and immediately they departed, and returned to the city.

As soon as they had entered the palace, Shahriyár caused his wife to be beheaded, and in like manner the women and black slaves; and thenceforth he made it his regular custom, every time that he took a virgin to his bed, to kill her at the expiration of the night. Thus he continued to do during a period of three years; and the people raised an outcry against him, and fled with their daughters, and there remained not a virgin in the city of a sufficient age for marriage. Such was the case when the King ordered the Wezeer to bring him a virgin according to his custom; and the Wezeer went forth and searched, and found none; and he went back to his house enraged and vexed, fearing what the King might do to him.

Now the Wezeer had two daughters; the elder of whom was named Shahrazád; and the younger, Dunyázád. The former had read various books of histories, and the lives of preceding kings, and stories of past generations: it is asserted that she had collected together a thousand books of histories, relating to preceding generations and kings, and works of the poets: and she said to her father on this occasion, Why do I see thee thus changed, and oppressed with solicitude and sorrows? It has been said by one of the poets:—

Tell him who is oppressed with anxiety, that anxiety will not last:

As happiness passeth away, so passeth away anxiety.

When the Wezeer heard these words from his daughter, he related to her all that had happened to him with regard to the King: upon which she said, By Allah, O my father, give me in marriage to this King: either I shall die, and be a ransom for one of the daughters of the Muslims, or I shall live, and be the cause of their deliverance from him.—I conjure thee by Allah, exclaimed he, that thou expose not thyself to such peril:—but she said, It must be so. Then, said he, I fear for thee that the same will befall thee that happened in the case of the ass and the bull and the husbandman.—And what, she asked, was that, O my father.

Know, O my daughter, said the Wezeer, that there was a certain merchant, who possessed wealth and cattle, and had a wife and children; and God, whose name be exalted, had also endowed him with the knowledge of the languages of beasts and birds. The abode of this merchant was in the country; and he had, in his house, an ass and a bull. When the bull came to the place where the ass was tied, he found it swept and sprinkled; in his manger were sifted barley and sifted cut straw, and the ass was lying at his ease; his master being accustomed only to ride him occasionally, when business required, and soon to return: and it happened, one day, that the merchant overheard the bull saying to the ass, May thy food benefit thee! I am oppressed with fatigue, while thou art enjoying repose: thou eatest sifted barley, and men serve thee; and it is only occasionally that thy master rides thee, and returns; while I am continually employed in ploughing, and turning the mill.—The ass answered, When thou goest out to the field, and they place the yoke upon thy neck, lie down, and do not rise again, even if they beat thee; or, if thou rise, lie down a second time; and when they take thee back, and place the beans before thee, eat them not, as though thou wert sick: abstain from eating and drinking a day, or two days, or three; and so shalt thou find rest from trouble and labour.—Accordingly, when the driver came to the bull with his fodder, he ate scarcely any of it; and on the morrow, when the driver came again to take him to plough, he found him apparently quite infirm: so the merchant said, Take the ass, and make him draw the plough in his stead all the day. The man did so; and when the ass returned at the close of the day, the bull thanked him for the favour he had conferred upon him by relieving him of his trouble on that day; but the ass returned him no answer, for he repented most grievously. On the next day, the ploughman came again, and took the ass, and ploughed with him till evening; and the ass returned with his neck flayed by the yoke, and reduced to an extreme state of weakness; and the bull looked upon him, and thanked and praised him. The ass exclaimed, I was living at ease, and nought but my meddling hath injured me! Then said he to the bull, Know that I am one who would give thee good advice: I heard our master say, If the bull rise not from his place, take him to the butcher, that he may kill him, and make a naṭạ of his skin:—I am therefore in fear for thee, and so I have given thee advice; and peace be on thee!—When the bull heard these words of the ass, he thanked him, and said, To-morrow I will go with alacrity:—so he ate the whole of his fodder, and even licked the manger.—Their master, meanwhile, was listening to their conversation.

On the following morning, the merchant and his wife went to the bull’s crib, and sat down there; and the driver came, and took out the bull; and when the bull saw his master, he shook his tail, and showed his alacrity by sounds and actions, bounding about in such a manner that the merchant laughed until he fell backwards. His wife, in surprise, asked him, At what dost thou laugh? He answered, At a thing that I have heard and seen; but I cannot reveal it; for if I did, I should die. She said, Thou must inform me of the cause of thy laughter, even if thou die.—I cannot reveal it, said he: the fear of death prevents me.—Thou laughedst only at me, she said; and she ceased not to urge and importune him until he was quite overcome and distracted. So he called together his children, and sent for the Ḳáḍee and witnesses, that he might make his will, and reveal the secret to her, and die: for he loved her excessively, since she was the daughter of his paternal uncle, and the mother of his children, and he had lived with her to the age of a hundred and twenty years. Having assembled her family and his neighbours, he related to them his story, and told them that as soon as he revealed his secret he must die; upon which every one present said to her, We conjure thee by Allah that thou give up this affair, and let not thy husband, and the father of thy children, die. But she said, I will not desist until he tell me, though he die for it. So they ceased to solicit her; and the merchant left them, and went to the stable to perform the ablution, and then to return, and tell them the secret, and die.

Now he had a cock, with fifty hens under him, and he had also a dog; and he heard the dog call to the cock, and reproach him, saying, Art thou happy when our master is going to die? The cock asked, How so?—and the dog related to him the story; upon which the cock exclaimed, By Allah! our master has little sense: I have fifty wives; and I please this, and provoke that; while he has but one wife, and cannot manage this affair with her: why does he not take some twigs of the mulberry-tree, and enter her chamber, and beat her until she dies or repents? She would never, after that, ask him a question respecting anything.—And when the merchant heard the words of the cock, as he addressed the dog, he recovered his reason, and made up his mind to beat her.—Now, said the Wezeer to his daughter Shahrazád, perhaps I may do to thee as the merchant did to his wife. She asked, And what did he? He answered, He entered her chamber, after he had cut off some twigs of the mulberry-tree, and hidden them there; and then said to her, Come into the chamber, that I may tell thee the secret while no one sees me, and then die:—and when she had entered, he locked the chamber-door upon her, and beat her until she became almost senseless and cried out, I repent:—and she kissed his hands and his feet, and repented, and went out with him; and all the company, and her own family, rejoiced; and they lived together in the happiest manner until death.

When the Wezeer’s daughter heard the words of her father, she said to him, It must be as I have requested. So he arrayed her, and went to the King Shahriyár. Now she had given directions to her young sister, saying to her, When I have gone to the King, I will send to request thee to come; and when thou comest to me, and seest a convenient time, do thou say to me, O my sister, relate to me some strange story to beguile our waking hour:—and I will relate to thee a story that shall, if it be the will of God, be the means of procuring deliverance.

Her father, the Wezeer, then took her to the King, who, when he saw him, was rejoiced, and said, Hast thou brought me what I desired? He answered, Yes. When the King, therefore, introduced himself to her, she wept; and he said to her, What aileth thee? She answered, O King, I have a young sister, and I wish to take leave of her. So the King sent to her; and she came to her sister, and embraced her, and sat near the foot of the bed; and after she had waited for a proper opportunity, she said, By Allah! O my sister, relate to us a story to beguile the waking hour of our night. Most willingly, answered Shahrazád, if this virtuous King permit me. And the King, hearing these words, and being restless, was pleased with the idea of listening to the story; and thus, on the first night of the thousand and one, Shahrazád commenced her recitations.

Chapter I

Commencing with the first night, and ending with the part of the third.

The Story of the Merchant and the Jinnee

It has been related to me, O happy King, said Shahrazád, that there was a certain merchant who had great wealth, and traded extensively with surrounding countries; and one day he mounted his horse, and journeyed to a neighbouring country to collect what was due to him, and, the heat oppressing him, he sat under a tree, in a garden, and put his hand into his saddle-bag, and ate a morsel of bread and a date which were among his provisions. Having eaten the date, he threw aside the stone, and immediately there appeared before him an ‘Efreet, of enormous height, who, holding a drawn sword in his hand, approached him, and said, Rise, that I may kill thee, as thou hast killed my son. The merchant asked him, How have I killed thy son? He answered, When thou atest the date, and threwest aside the stone, it struck my son upon the chest, and, as fate had decreed against him, he instantly died.

The merchant, on hearing these words, exclaimed, Verily to God we belong, and verily to Him we must return! There is no strength nor power but in God, the High, the Great! If I killed him, I did it not intentionally, but without knowing it; and I trust in thee that thou wilt pardon me.—The Jinnee answered, Thy death is indispensable, as thou hast killed my son:—and so saying, he dragged him, and threw him on the ground, and raised his arm to strike him with the sword. The merchant, upon this, wept bitterly, and said to the Jinnee, I commit my affair unto God, for no one can avoid what He hath decreed:—and he continued his lamentation, repeating the following verses:—

Time consists of two days; this, bright; and that, gloomy: and life, of two moieties; this, safe; and that, fearful.

Say to him who hath taunted us on account of misfortunes, Doth fortune oppose any but the eminent?

Dost thou not observe that corpses float upon the sea, whilethe precious pearls remain in its furthest depths?

When the hands of time play with us, misfortune is imparted to us by its protracted kiss.

In the heaven are stars that cannot be numbered; but none is eclipsed save the sun and the moon.

How many green and dry trees are on the earth; but none is assailed with stones save that which beareth fruit!

Thou thoughtest well of the days when they went well with thee, and fearedst not the evil that destiny was bringing.

—When he had finished reciting these verses, the Jinnee said to him, Spare thy words, for thy death is unavoidable.

Then said the merchant, Know, O ‘Efreet, that I have debts to pay, and I have much property, and children, and a wife, and I have pledges also in my possession: let me, therefore, go back to my house, and give to every one his due, and then I will return to thee: I bind myself by a vow and covenant that I will return to thee, and thou shalt do what thou wilt; and God is witness of what I say.—Upon this, the Jinnee accepted his covenant, and liberated him; granting him a respite until the expiration of the year.

The merchant, therefore, returned to his town, accomplished all that was upon his mind to do, paid every one what he owed him, and informed his wife and children of the event which had befallen him; upon hearing which, they and all his family and women wept. He appointed a guardian over his children, and remained with his family until the end of the year; when he took his grave-clothes under his arm, bade farewell to his household and neighbours, and all his relations, and went forth, in spite of himself; his family raising cries of lamentation, and shrieking.

He proceeded until he arrived at the garden before mentioned; and it was the first day of the new year; and as he sat, weeping for the calamity which he expected soon to befall him, a sheykh, advanced in years, approached him, leading a gazelle with a chain attached to its neck. This sheykh saluted the merchant, wishing him a long life, and said to him, What is the reason of thy sitting alone in this place, seeing that it is a resort of the Jinn? The merchant therefore informed him of what had befallen him with the ‘Efreet, and of the cause of his sitting there; at which the sheykh, the owner of the gazelle, was astonished, and said, By Allah, O my brother, thy faithfulness is great, and thy story is wonderful! if it were engraved upon the intellect, it would be a lesson to him who would be admonished!—And he sat down by his side, and said, By Allah, O my brother, I will not quit this place until I see what will happen unto thee with this ‘Efreet. So he sat down, and conversed with him. And the merchant became almost senseless; fear entered him, and terror, and violent grief, and excessive anxiety. And as the owner of the gazelle sat by his side, lo, a second sheykh approached them, with two black hounds, and inquired of them, after saluting them, the reason of their sitting in that place, seeing that it was a resort of the Jánn: and they told him the story from beginning to end. And he had hardly sat down when there approached them a third sheykh, with a dapple mule; and he asked them the same question, which was answered in the same manner.

Immediately after, the dust was agitated, and became an enormous revolving pillar, approaching them from the midst of the desert; and this dust subsided, and behold, the Jinnee, with a drawn sword in his hand; his eyes casting forth sparks of fire. He came to them, and dragged from them the merchant, and said to him, Rise, that I may kill thee, as thou killedst my son, the vital spirit of my heart. And the merchant wailed and wept; and the three sheykhs also manifested their sorrow by weeping and crying aloud and wailing: but the first sheykh, who was the owner of the gazelle, recovering his self-possession, kissed the hand of the ‘Efreet, and said to him, O thou Jinnee, and crown of the kings of the Jánn, if I relate to thee the story of myself and this gazelle, and thou find it to be wonderful, and more so than the adventure of this merchant, wilt thou give up to me a third of thy claim to his blood? He answered, Yes, O sheykh; if thou relate to me the story, and I find it to be as thou hast said, I will give up to thee a third of my claim to his blood.

The Story of the First Sheykh and the Gazelle

Then said the sheykh, Know, O ‘Efreet, that this gazelle is the daughter of my paternal uncle, and she is of my flesh and my blood. I took her as my wife when she was young, and lived with her about thirty years; but I was not blessed with a child by her; so I took to me a concubine slave, and by her I was blessed with a male child, like the rising full moon, with beautiful eyes, and delicately-shaped eyebrows, and perfectly-formed limbs; and he grew up by little and little until he attained the age of fifteen years. At this period, I unexpectedly had occasion to journey to a certain city, and went thither with a great stock of merchandise.

Now my cousin, this gazelle, had studied enchantment and divination from her early years; and during my absence, she transformed the youth above mentioned into a calf; and his mother, into a cow; and committed them to the care of the herdsman: and when I returned, after a long time, from my journey, I asked after my son and his mother, and she said, Thy slave is dead, and thy son hath fled, and I know not whither he is gone. After hearing this, I remained for the space of a year with mourning heart and weeping eye, until the Festival of the Sacrifice; when I sent to the herdsman, and ordered him to choose for me a fat cow; and he brought me one, and it was my concubine, whom this gazelle had enchanted. I tucked up my skirts and sleeves, and took the knife in my hand, and prepared myself to slaughter her; upon which she moaned and cried so violently that I left her, and ordered the herdsman to kill and skin her: and he did so, but found in her neither fat nor flesh, nor anything but skin and bone; and I repented of slaughtering her, when repentance was of no avail. I therefore gave her to the herdsman, and said to him, Bring me a fat calf: and he brought me my son, who was transformed into a calf. And when the calf saw me, he broke his rope, and came to me, and fawned upon me, and wailed and cried, so that I was moved with pity for him; and I said to the herdsman, Bring me a cow, and let this—

Here Shahrazád perceived the light of morning, and discontinued the recitation with which she had been allowed thus far to proceed. Her sister said to her, How excellent is thy story! and how pretty! and how pleasant! and how sweet!—but she answered, What is this in comparison with that which I will relate to thee in the next night, if I live, and the King spare me! And the King said, By Allah, I will not kill her until I hear the remainder of her story. Thus they pleasantly passed the night until the morning, when the King went forth to his hall of judgment, and the Wezeer went thither with the grave-clothes under his arm: and the King gave judgment, and invested and displaced, until the close of the day, without informing the Wezeer of that which had happened; and the minister was greatly astonished. The court was then dissolved; and the King returned to the privacy of his palace.

[On the second and each succeeding night, Shahrazád continued so to interest King Shahriyár by her stories as to induce him to defer putting her to death, in expectation that her fund of amusing tales would soon be exhausted; and as this is expressed in the original work in nearly the same words at the close of every night, such repetitions will in the present translation be omitted.]

When the sheykh, continued Shahrazád, observed the tears of the calf, his heart sympathized with him, and he said to the herdsman, Let this calf remain with the cattle—Meanwhile, the Jinnee wondered at this strange story; and the owner of the gazelle thus proceeded.

O lord of the kings of the Jánn, while this happened, my cousin, this gazelle, looked on, and said, Slaughter this calf; for he is fat: but I could not do it; so I ordered the herdsman to take him back; and he took him and went away. And as I was sitting, on the following day, he came to me, and said, O my master, I have to tell thee something that thou wilt be rejoiced to hear; and a reward is due to me for bringing good news. I answered, Well:—and he said, O merchant, I have a daughter who learned enchantment in her youth from an old woman in our family; and yesterday, when thou gavest me the calf, I took him to her, and she looked at him, and covered her face, and wept, and then laughed, and said, O my father, hath my condition become so degraded in thy opinion that thou bringest before me strange men?—Where, said I, are any strange men? and wherefore didst thou weep and laugh? She answered, This calf that is with thee is the son of our master, the merchant, and the wife of our master hath enchanted both him and his mother; and this was the reason of my laughter; but as to the reason of my weeping, it was on account of his mother, because his father had slaughtered her.—And I was excessively astonished at this; and scarcely was I certain that the light of morning had appeared when I hastened to inform thee.

When I heard, O Jinnee, the words of the herdsman, I went forth with him, intoxicated without wine, from the excessive joy and happiness that I received, and arrived at his house, where his daughter welcomed me, and kissed my hand; and the calf came to me, and fawned upon me. And I said to the herdsman’s daughter, Is that true which thou hast said respecting this calf? She answered, Yes, O my master; he is verily thy son, and the vital spirit of thy heart.—O maiden, said I, if thou wilt restore him, all the cattle and other property of mine that thy father hath under his care shall be thine. Upon this, she smiled, and said, O my master, I have no desire for the property unless on two conditions: the first is, that thou shalt marry me to him; and the second, that I shall enchant her who enchanted him, and so restrain her; otherwise, I shall not be secure from her artifice. On hearing, O Jinnee, these her words, I said, And thou shalt have all the property that is under the care of thy father besides; and as to my cousin, even her blood shall be lawful to thee. So, when she heard this, she took a cup, and filled it with water, and repeated a spell over it, and sprinkled with it the calf, saying to him, If God created thee a calf, remain in this form, and be not changed; but if thou be enchanted, return to thy original form, by permission of God, whose name be exalted!— upon which he shook, and became a man; and I threw myself upon him, and said, I conjure thee by Allah that thou relate to me all that my cousin did to thee and to thy mother. So he related to me all that had happened to them both; and I said to him, O my son, God hath given thee one to liberate thee, and to avenge thee:—and I married to him, O Jinnee, the herdsman’s daughter; after which, she transformed my cousin into this gazelle. And as I happened to pass this way, I saw this merchant, and asked him what had happened to him; and when he had informed me, I sat down to see the result.—This is my story. The Jinnee said, This is a wonderful tale; and I give up to thee a third of my claim to his blood.

The second sheykh, the owner of the two hounds, then advanced, and said to the Jinnee, If I relate to thee the story of myself and these hounds, and thou find it to be in like manner wonderful, wilt thou remit to me, also, a third of thy claim to the blood of this merchant? The Jinnee answered, Yes.

The Story of the Second Sheykh and the Two Black Hounds

Then said the sheykh, Know, O lord of the kings of the Jánn, that these two hounds are my brothers. My father died, and left to us three thousand pieces of gold; and I opened a shop to sell and buy. But one of my brothers made a journey, with a stock of merchandise, and was absent from us for the space of a year with the caravans; after which, he returned destitute. I said to him, Did I not advise thee to abstain from travelling? But he wept, and said, O my brother, God, to whom be ascribed all might and glory, decreed this event; and there is no longer any profit in these words: I have nothing left. So I took him up into the shop, and then went with him to the bath, and clad him in a costly suit of my own clothing; after which, we sat down together to eat; and I said to him, O my brother, I will calculate the gain of my shop during the year, and divide it, exclusive of the principal, between me and thee. Accordingly, I made the calculation, and found my gain to amount to two thousand pieces of gold; and I praised God, to whom be ascribed all might and glory, and rejoiced exceedingly, and divided the gain in two equal parts between myself and him.—My other brother then set forth on a journey; and after a year, returned in the like condition; and I did unto him as I had done to the former.

After this, when we had lived together for some time, my brothers again wished to travel, and were desirous that I should accompany them; but I would not. What, said I, have ye gained in your travels, that I should expect to gain? They importuned me; but I would not comply with their request; and we remained selling and buying in our shops a whole year. Still, however, they persevered in proposing that we should travel, and I still refused, until after the lapse of six entire years, when at last I consented, and said to them, O my brothers, let us calculate what property we possess. We did so, and found it to be six thousand pieces of gold: and I then said to them, We will bury half of it in the earth, that it may be of service to us if any misfortune befall us, in which case each of us shall take a thousand pieces, with which to traffic. Excellent is thy advice, said they. So I took the money and divided it into two equal portions, and buried three thousand pieces of gold; and of the other half, I gave to each of them a thousand pieces. We then prepared merchandise, and hired a ship, and embarked our goods, and proceeded on our voyage for the space of a whole month, at the expiration of which we arrived at a city, where we sold our merchandise; and for every piece of gold we gained ten.

And when we were about to set sail again, we found, on the shore of the sea, a maiden clad in tattered garments, who kissed my hand, and said to me, O my master, art thou possessed of charity and kindness? If so, I will requite thee for them. I answered, Yes, I have those qualities, though thou requite me not. Then said she, O my master, accept me as thy wife, and take me to thy country; for I give myself to thee: act kindly towards me; for I am one who requires to be treated with kindness and charity, and who will requite thee for so doing; and let not my present condition at all deceive thee. When I heard these words, my heart was moved with tenderness towards her, in order to the accomplishment of a purpose of God, to whom be ascribed all might and glory; and I took her, and clothed her, and furnished for her a place in the ship in a handsome manner, and regarded her with kind and respectful attention.

We then set sail; and I became most cordially attached to my wife, so that, on her account, I neglected the society of my brothers, who, in consequence, became jealous of me, and likewise envied me my wealth, and the abundance of my merchandise; casting the eyes of covetousness upon the whole of the property. They therefore consulted together to kill me, and take my wealth; saying, Let us kill our brother, and all the property shall be ours:—and the devil made these actions to seem fair in their eyes; so they came to me while I was sleeping by the side of my wife, and took both of us up, and threw us into the sea. But as soon as my wife awoke, she shook herself, and became transformed into a Jinneeyeh. She immediately bore me away, and placed me upon an island, and, for a while, disappeared. In the morning, however, she returned, and said to me, I am thy wife, who carried thee, and rescued thee from death, by permission of God, whose name be exalted. Know that I am a Jinneeyeh: I saw thee, and my heart loved thee for the sake of God; for I am a believer in God and his Apostle, God bless and save him! I came to thee in the condition in which thou sawest me, and thou didst marry me; and see, I have rescued thee from drowning. But I am incensed against thy brothers, and I must kill them.—When I heard her tale, I was astonished, and thanked her for what she had done;—But, said I, as to the destruction of my brothers, it is not what I desire. I then related to her all that had happened between myself and them from first to last; and when she had heard it, she said, I will, this next night, fly to them, and sink their ship, and destroy them. But I said, I conjure thee by Allah that thou do it not; for the author of the proverb saith, O thou benefactor of him who hath done evil, the action that he hath done is sufficient for him:—besides, they are at all events my brothers. She still, however, said, They must be killed;—and I continued to propitiate her towards them: and at last she lifted me up, and soared through the air, and placed me on the roof of my house.

Having opened the doors, I dug up what I had hidden in the earth; and after I had saluted my neighbours, and bought merchandise, I opened my shop. And in the following night, when I entered my house, I found these two dogs tied up in it; and as soon as they saw me, they came to me, and wept, and clung to me; but I knew not what had happened until immediately my wife appeared before me, and said, These are thy brothers. And who, said I, hath done this unto them? She answered, I sent to my sister and she did it; and they shall not be restored until after the lapse of ten years. And I was now on my way to her, that she might restore them, as they have been in this state ten years, when I saw this man, and, being informed of what had befallen him, I determined not to quit the place until I should have seen what would happen between thee and him.—This is my story.—Verily, said the Jinnee, it is a wonderful tale; and I give up to thee a third of the claim that I had to his blood on account of his offence.

Upon this, the third sheykh, the owner of the mule, said to the Jinnee, As to me, break not my heart if I relate to thee nothing more than this:—

The Story of the Third Sheykh and the Mule

The mule that thou seest was my wife: she became enamoured of a black slave; and when I discovered her with him, she took a mug of water, and, having uttered a spell over it, sprinkled me, and transformed me into a dog. In this state, I ran to the shop of a butcher, whose daughter saw me, and, being skilled in enchantment, restored me to my original form, and instructed me to enchant my wife in the manner thou beholdest.—And now I hope that thou wilt remit to me also a third of the merchant’s offence. Divinely was he gifted who said,

Sow good, even on an unworthy soil; for it will not be lost wherever it is sown.

When the sheykh had thus finished his story, the Jinnee shook with delight, and remitted the remaining third of his claim to the merchant’s blood. The merchant then approached the sheykhs, and thanked them, and they congratulated him on his safety; and each went his way.

But this, said Shahrazád, is not more wonderful than the story of the fisherman. The King asked her, And what is the story of the fisherman? And she related it as follows:—

Chapter II

Commencing with Part of the Third Night, and Ending with Part of the Ninth

The Story of the Fisherman

There was a certain fisherman, advanced in age, who had a wife and three children; and though he was in indigent circumstances, it was his custom to cast his net, every day, no more than four times. One day he went forth at the hour of noon to the shore of the sea, and put down his basket, and cast his net, and waited until it was motionless in the water, when he drew together its strings, and found it to be heavy: he pulled, but could not draw it up: so he took the end of the cord, and knocked a stake into the shore, and tied the cord to it. He then stripped himself, and dived round the net, and continued to pull until he drew it out: whereupon he rejoiced, and put on his clothes; but when he came to examine the net, he found in it the carcass of an ass. At the sight of this he mourned, and exclaimed, There is no strength nor power but in God, the High, the Great! This is a strange piece of fortune!—And he repeated the following verse:—

O thou who occupiest thyself in the darkness of night, and in peril! Spare thy trouble; for the support of Providence is not obtained by toil!

He then disencumbered his net of the dead ass, and wrung it out; after which he spread it, and descended into the sea, and—exclaiming, In the name of God!—cast it again, and waited till it had sunk and was still, when he pulled it, and found it more heavy and more difficult to raise than on the former occasion. He therefore concluded that it was full of fish: so he tied it, and stripped, and plunged and dived, and pulled until he raised it, and drew it upon the shore; when he found in it only a large jar, full of sand and mud; on seeing which, he was troubled in his heart, and repeated the following words of the poet:—

O angry fate, forbear! or, if thou wilt not forbear, relent!

Neither favour from fortune do I gain, nor profit from the work of my hands,

I came forth to seek my sustenance, but have found it to be exhausted.

How many of the ignorant are in splendour! and how many of the wise, in obscurity!

So saying, he threw aside the jar, and wrung out and cleansed his net; and, begging the forgiveness of God for his impatience, returned to the sea the third time, and threw the net, and waited till it had sunk and was motionless: he then drew it out, and found in it a quantity of broken jars and pots.

Upon this, he raised his head towards heaven, and said, O God, Thou knowest that I cast not my net more than four times; and I have now cast it three times! Then—exclaiming, In the name of God!—he cast the net again into the sea, and waited till it was still; when he attempted to draw it up, but could not, for it clung to the bottom. And he exclaimed, There is no strength nor power but in God!—and stripped himself again, and dived round the net, and pulled it until he raised it upon the shore; when he opened it, and found in it a bottle of brass, filled with something, and having its mouth closed with a stopper of lead, bearing the impression of the seal of our lord Suleymán. At the sight of this, the fisherman was rejoiced, and said, This I will sell in the copper-market; for it is worth ten pieces of gold. He then shook it, and found it to be heavy, and said, I must open it, and see what is in it, and store it in my bag; and then I will sell the bottle in the copper-market. So he took out a knife, and picked at the lead until he extracted it from the bottle. He then laid the bottle on the ground, and shook it, that its contents might pour out; but there came forth from it nothing but smoke, which ascended towards the sky, and spread over the face of the earth; at which he wondered excessively. And after a little while, the smoke collected together, and was condensed, and then became agitated, and was converted into an ‘Efreet, whose head was in the clouds, while his feet rested upon the ground: his head was like a dome: his hands were like winnowing forks; and his legs, like masts: his mouth resembled a cavern: his teeth were like stones; his nostrils, like trumpets; and his eyes, like lamps; and he had dishevelled and dust-coloured hair.

When the fisherman beheld this ‘Efreet, the muscles of his sides quivered, his teeth were locked together, his spittle dried up, and he saw not his way. The ‘Efreet, as soon as he perceived him, exclaimed, There is no deity but God: Suleymán is the Prophet of God. O Prophet of God, slay me not; for I will never again oppose thee in word, or rebel against thee in deed!—O Márid, said the fisherman, dost thou say, Suleymán is the Prophet of God? Suleymán hath been dead a thousand and eight hundred years; and we are now in the end of time. What is thy history, and what is thy tale, and what was the cause of thy entering this bottle? When the Márid heard these words of the fisherman, he said, There is no deity but God! Receive news, O fisherman!—Of what, said the fisherman, dost thou give me news? He answered, Of thy being instantly put to a most cruel death. The fisherman exclaimed, Thou deservest, for this news, O master of the ‘Efreets, the withdrawal of protection from thee, O thou remote! Wherefore wouldst thou kill me? and what requires thy killing me, when I have liberated thee from the bottle, and rescued thee from the bottom of the sea, and brought thee up upon the dry land?—The ‘Efreet answered, Choose what kind of death thou wilt die, and in what manner thou shalt be killed.—What is my offence, said the fisherman, that this should be my recompense from thee? The ‘Efreet replied, Hear my story, O fisherman.—Tell it then, said the fisherman, and be short in thy words; for my soul hath sunk down to my feet.

Know then, said he, that I am one of the heretical Jinn: I rebelled against Suleymán the son of Dáood: I and Ṣakhr the Jinnee; and he sent to me his Wezeer, Áṣaf the son of Barkhiyà, who came upon me forcibly, and took me to him in bonds, and placed me before him: and when Suleymán saw me, he offered up a prayer for protection against me, and exhorted me to embrace the faith, and to submit to his authority; but I refused; upon which he called for this bottle, and confined me in it, and closed it upon me with the leaden stopper, which he stamped with the Most Great Name: he then gave orders to the Jinn, who carried me away, and threw me into the midst of the sea. There I remained a hundred years; and I said in my heart, Whosoever shall liberate me, I will enrich him for ever:—but the hundred years passed over me, and no one liberated me: and I entered upon another hundred years; and I said, Whosoever shall liberate me, I will open to him the treasures of the earth;—but no one did so: and four hundred years more passed over me, and I said, Whosoever shall liberate me, I will perform for him three wants:— but still no one liberated me. I then fell into a violent rage, and said within myself, Whosoever shall liberate me now, I will kill him; and only suffer him to choose in what manner he will die. And lo, now thou hast liberated me, and I have given thee thy choice of the manner in which thou wilt die.

When the fisherman had heard the story of the ‘Efreet, he exclaimed, O Allah! that I should not have liberated thee but in such a time as this! Then said he to the ‘Efreet, Pardon me, and kill me not, and so may God pardon thee; and destroy me not, lest God give power over thee to one who will destroy thee. The Márid answered, I must positively kill thee; therefore choose by what manner of death thou wilt die. The fisherman then felt assured of his death; but he again implored the ‘Efreet, saying, Pardon me by way of gratitude for my liberating thee.—Why, answered the ‘Efreet, I am not going to kill thee but for that very reason, because thou hast liberated me.—O Sheykh of the ‘Efreets, said the fisherman, do I act kindly towards thee, and dost thou recompense me with baseness? But the proverb lieth not that saith,—

We did good to them, and they returned us the contrary; and such, by my life, is the conduct of the wicked. Thus he who acteth kindly to the undeserving is recompensed in the same manner as the aider of Umm-’Ámir.

The ‘Efreet, when he heard these words, answered by saying, Covet not life, for thy death is unavoidable. Then said the fisherman within himself, This is a Jinnee, and I am a man; and God hath given me sound reason; therefore, I will now plot his destruction with my art and reason, like as he hath plotted with his cunning and perfidy. So he said to the ‘Efreet, Hast thou determined to kill me? He answered, Yes. Then said he, By the Most Great Name engraved upon the seal of Suleymán, I will ask thee one question; and wilt thou answer it to me truly? On hearing the mention of the Most Great Name, the ‘Efreet was agitated, and trembled, and replied, Yes; ask, and be brief. The fisherman then said, How wast thou in this bottle? It will not contain thy hand or thy foot; how then can it contain thy whole body?—Dost thou not believe that I was in it? said the ‘Efreet. The fisherman answered, I will never believe thee until I see thee in it. Upon this, the ‘Efreet shook, and became converted again into smoke, which rose to the sky, and then became condensed, and entered the bottle by little and little, until it was all enclosed; when the fisherman hastily snatched the sealed leaden stopper, and, having replaced it in the mouth of the bottle, called out to the ‘Efreet, and said, Choose in what manner of death thou wilt die. I will assuredly throw thee here into the sea, and build me a house on this spot; and whosoever shall come here, I will prevent his fishing in this place, and will say to him, Here is an ‘Efreet, who, to any person that liberates him, will propose various kinds of death, and then give him his choice of one of them. On hearing these words of the fisherman, the ‘Efreet endeavoured to escape; but could not, finding himself restrained by the impression of the seal of Suleymán, and thus imprisoned by the fisherman as the vilest and filthiest and least of ‘Efreets. The fisherman then took the bottle to the brink of the sea. The ‘Efreet exclaimed, Nay! nay!—to which the fisherman answered, Yea, without fail! yea, without fail! The Márid then addressing him with a soft voice and humble manner, said, What dost thou intend to do with me, O fisherman? He answered, I will throw thee into the sea; and if thou hast been there a thousand and eight hundred years, I will make thee to remain there until the hour of judgment. Did I not say to thee, Spare me, and so may God spare thee; and destroy me not, lest God destroy thee? But thou didst reject my petition, and wouldest nothing but treachery; therefore God hath caused thee to fall into my hand, and I have betrayed thee.—Open to me, said the ‘Efreet, that I may confer benefits upon thee. The fisherman replied, Thou liest, thou accursed! I and thou are like the Wezeer of King Yoonán and the sage Doobán.—What, said the ‘Efreet, was the case of the Wezeer of King Yoonán and the sage Doobán, and what is their story? The fisherman answered as follows:—

The Story of King Yoonán and the Sage of Doobán

Know, O ‘Efreet, that there was, in former times, in the country of the Persians, a monarch who was called King Yoonán, possessing great treasures and numerous forces, valiant, and having troops of every description; but he was afflicted with leprosy, which the physicians and sages had failed to remove; neither their potions, nor powders, nor ointments were of any benefit to him; and none of the physicians was able to cure him. At length there arrived at the city of this king a great sage, stricken in years, who was called the sage Doobán: he was acquainted with ancient Greek, Persian, modern Greek, Arabic, and Syriac books, and with medicine and astrology, both with respect to their scientific principles and the rules of their practical applications for good and evil; as well as the properties of plants, dried and fresh, the injurious and the useful: he was versed in the wisdom of the philosophers, and embraced a knowledge of all the medical and other sciences. After this sage had arrived in the city, and remained in it a few days, he heard of the case of the King, of the leprosy with which God had afflicted him, and that the physicians and men of science had failed to cure him. In consequence of this information, he passed the next night in deep study; and when the morning came, and diffused its light, and the sun saluted the Ornament of the Good, he attired himself in the richest of his apparel, and presented himself before the King. Having kissed the ground before him, and offered up a prayer for the continuance of his power and happiness, and greeted him in the best manner he was able, he informed him who he was, and said, O King, I have heard of the disease which hath attacked thy person, and that many of the physicians are unacquainted with the means of removing it; and I will cure thee without giving thee to drink any potion, or anointing thee with ointment. When King Yoonán heard his words, he wondered, and said to him, How wilt thou do this? By Allah, if thou cure me, I will enrich thee and thy children’s children, and I will heap favours upon thee, and whatever thou shalt desire shall be thine, and thou shalt be my companion and my friend.—He then bestowed upon him a robe of honour, and other presents, and said to him, Wilt thou cure me of this disease without potion or ointment? He answered, Yes; I will cure thee without any discomfort to thy person. And the King was extremely astonished, and said, O Sage, at what time, and on what day, shall that which thou hast proposed to me be done? Hasten it, O my Son.—He answered, I hear and obey.

He then went out from the presence of the King, and hired a house, in which he deposited his books, and medicines, and drugs. Having done this, he selected certain of his medicines and drugs, and made a goff-stick, with a hollow handle, into which he introduced them; after which he made a ball for it, skilfully adapted; and on the following day, after he had finished these, he went again to the King, and kissed the ground before him, and directed him to repair to the horse-course, and to play with the ball and goff-stick. The King, attended by his Emeers and Chamberlains and Wezeers, went thither, and, as soon as he arrived there, the sage Doobán presented himself before him, and handed to him the goff-stick, saying, Take this goff-stick, and grasp it thus, and ride along the horse-course, and strike the ball with it with all thy force, until the palm of thy hand and thy whole body become moist with perspiration, when the medicine will penetrate into thy hand, and pervade thy whole body; and when thou hast done this, and the medicine remains in thee, return to thy palace, and enter the bath, and wash thyself, and sleep: then shalt thou find thyself cured: and peace be on thee. So King Yoonán took the goff-stick from the sage, and grasped it in his hand, and mounted his horse; and the ball was thrown before him, and he urged his horse after it until he overtook it, when he struck it with all his force; and when he had continued this exercise as long as was necessary, and bathed and slept, he looked upon his skin, and not a vestige of the leprosy remained: it was clear as white silver. Upon this he rejoiced exceedingly; his heart was dilated, and he was full of happiness.

On the following morning he entered the council-chamber, and sat upon his throne; and the Chamberlains and great officers of his court came before him. The sage Doobán also presented himself; and when the King saw him, he rose to him in haste, and seated him by his side. Services of food were then spread before them, and the sage ate with the King, and remained as his guest all the day; and when the night approached, the King gave him two thousand pieces of gold, besides dresses of honour and other presents, and mounted him on his own horse, and so the sage returned to his house. And the King was astonished at his skill; saying, This man hath cured me by an external process, without anointing me with ointment: by Allah, this is consummate science; and it is incumbent on me to bestow favours and honours upon him, and to make him my companion and familiar friend as long as I live. He passed the night happy and joyful on account of his recovery, and when he arose, he went forth again, and sat upon his throne; the officers of his court standing before him, and the Emeers and Wezeers sitting on his right hand and on his left; and he called for the sage Doobán, who came, and kissed the ground before him; and the King rose, and seated him by his side, and ate with him, and greeted him with compliments: he bestowed upon him again a robe of honour and other presents, and, after conversing with him till the approach of night, gave orders that five other robes of honour should be given to him, and a thousand pieces of gold; and the sage departed, and returned to his house.

Again, when the next morning came, the King went as usual to his council-chamber, and the Emeers and Wezeers and Chamberlains surrounded him. Now there was, among his Wezeers, one of ill aspect, and of evil star; sordid, avaricious, and of an envious and malicious disposition; and when he saw that the King had made the sage Doobán his friend, and bestowed upon him these favours, he envied him this distinction, and meditated evil against him; agreeably with the adage which saith, There is no one void of envy;—and another, which saith, Tyranny lurketh in the soul: power manifesteth it, and weakness concealeth it. So he approached the King, and kissed the ground before him, and said, O King of the age, thou art he whose goodness extendeth to all men, and I have an important piece of advice to give thee: if I were to conceal it from thee, I should be a base-born wretch: therefore, if thou order me to impart it, I will do so. The King, disturbed by these words of the Wezeer, said, What is thy advice? He answered, O glorious King, it hath been said, by the ancients, He who looketh not to results, fortune will not attend him:—now I have seen the King in a way that is not right; since he hath bestowed favours upon his enemy, and upon him who desireth the downfall of his dominion: he hath treated him with kindness, and honoured him with the highest honours, and admitted him to the closest intimacy: I therefore fear, for the King, the consequence of this conduct.—At this the King was troubled, and his countenance changed; and he said, Who is he whom thou regardest as mine enemy, and to whom I shew kindness? He replied, O King, if thou hast been asleep, awake! I allude to the sage Doobán.—The King said, He is my intimate companion, and the dearest of men in my estimation; for he restored me by a thing that I merely held in my hand, and cured me of my disease which the physicians were unable to remove, and there is not now to be found one like to him in the whole world, from west to east. Wherefore, then, dost thou utter these words against him? I will, from this day, appoint him a regular salary and maintenance, and give him every month a thousand pieces of gold; and if I gave him a share of my kingdom it were but a small thing to do unto him. I do not think that thou hast said this from any other motive than that of envy. If I did what thou desirest, I should repent after it, as the man repented who killed his parrot.

The Story of the Husband and the Parrot

There was a certain merchant, of an excessively jealous disposition, having a wife endowed with perfect beauty, who had prevented him from leaving his home; but an event happened which obliged him to make a journey; and when he found his doing so to be indispensable, he went to the market in which birds were sold, and bought a parrot, which he placed in his house to act as a spy, that, on his return, she might inform him of what passed during his absence; for this parrot was cunning and intelligent, and remembered whatever she heard. So, when he had made his journey, and accomplished his business, he returned, and caused the parrot to be brought to him, and asked her respecting the conduct of his wife. She answered, Thy wife has a lover, who visited her every night during thy absence:—and when the man heard this, he fell into a violent rage, and went to his wife, and gave her a severe beating.

The woman imagined that one of the female slaves had informed him of what had passed between her and her paramour during his absence: she therefore called them together, and made them swear; and they all swore that they had not told their master anything of the matter; but confessed that they had heard the parrot relate to him what had passed. Having thus established, on the testimony of the slaves, the fact of the parrot’s having informed her husband of her intrigue, she ordered one of these slaves to grind with a hand-mill under the cage, another to sprinkle water from above, and a third to move a mirror from side to side, during the next night on which her husband was absent; and on the following morning, when the man returned from an entertainment at which he had been present, and inquired again of the parrot what had passed that night during his absence, the bird answered, O my master, I could neither see nor hear anything, on account of the excessive darkness, and thunder, and lightning, and rain. Now this happened during summer: so he said to her, What strange words are these? It is now summer, when nothing of what thou hast described ever happens.—The parrot, however, swore by Allah the Great that what she had said was true; and that it had so happened: upon which the man, not understanding the case, nor knowing the plot, became violently enraged, and took out the bird from the cage, and threw her down upon the ground with such violence that he killed her.

But after some days, one of his female slaves informed him of the truth; yet he would not believe it, until he saw his wife’s paramour going out from his house; when he drew his sword, and slew the traitor by a blow on the back of his neck: so also did he to his treacherous wife; and thus both of them went, laden with the sin which they had committed, to the fire; and the merchant discovered that the parrot had informed him truly of what she had seen; and he mourned grievously for her loss.

When the Wezeer heard these words of King Yoonán, he said, O King of great dignity, what hath this crafty sage—this man from whom nought but mischief proceedeth—done unto me, that I should be his enemy, and speak evil of him, and plot with thee to destroy him? I have informed thee respecting him in compassion for thee, and in fear of his despoiling thee of thy happiness; and if my words be not true, destroy me, as the Wezeer of Es-Sindibád was destroyed.—The King asked, How was that? And the Wezeer thus answered:—

The Story of the Envious Wezeer and the Prince and the Ghooleh

The King above mentioned had a son who was ardently fond of the chase; and he had a Wezeer whom he charged to be always with this son wherever he went. One day the son went forth to hunt, and his father’s Wezeer was with him; and as they rode together, they saw a great wild beast; upon which the Wezeer exclaimed to the Prince, Away after this wild beast! The King’s son pursued it until he was out of the sight of his attendants, and the beast also escaped from before his eyes in the desert; and while the Prince wandered in perplexity, not knowing whither to direct his course, he met in his way a damsel, who was weeping. He said to her, Who art thou?—and she answered, I am a daughter of one of the kings of India; I was in the desert, and slumber overtook me, and I fell from my horse in a state of insensibility, and being thus separated from my attendants, I lost my way. The Prince, on hearing this, pitied her forlorn state, and placed her behind him on his horse; and as they proceeded, they passed by a ruin, and the damsel said to him, O my master, I would alight here for a little while. The Prince therefore lifted her from his horse at this ruin; but she delayed so long to return, that he wondered wherefore she had loitered so, and entering after her, without her knowledge, perceived that she was a Ghooleh, and heard her say, My children, I have brought you to-day a fat young man:—on which they exclaimed, Bring him in to us, O mother! that we may fill our stomachs with his flesh. When the Prince heard their words, he felt assured of destruction; the muscles of his sides quivered, and fear overcame him, and he retreated. The Ghooleh then came forth, and, seeing that he appeared alarmed and fearful, and that he was trembling, said to him, Wherefore dost thou fear? He answered, I have an enemy of whom I am in fear. The Ghooleh said, Thou assertest thyself to be the son of the King. He replied, Yes.—Then, said she, wherefore dost thou not give some money to thine enemy, and so conciliate him? He answered, He will not be appeased with money, nor with anything but life; and therefore do I fear him: I am an injured man. She then said to him, If thou be an injured man, as thou affirmest, beg aid of God against thine oppressor, and He will avert from thee his mischievous design, and that of every other person whom thou fearest. Upon this, therefore, the Prince raised his head towards heaven, and said, O thou who answerest the distressed when he prayeth to Thee, and dispellest evil, assist me, and cause mine enemy to depart from me; for Thou art able to do whatsoever Thou wilt!—and the Ghooleh no sooner heard his prayer, than she departed from him. The Prince then returned to his father, and informed him of the conduct of the Wezeer; upon which the King gave orders that the minister should be put to death.

Continuation of the Story of King Yoonán and the Safe Doobán

And thou, O King, continued the Wezeer of King Yoonán, if thou trust in this sage, he will kill thee in the foulest manner. If thou continue to bestow favours upon him, and to make him thine intimate companion, he will plot thy destruction. Dost thou not see that he hath cured thee of the disease by external means, by a thing that thou heldest in thy hand? Therefore thou art not secure against his killing thee by a thing that thou shalt hold in the same manner.—King Yoonán answered, Thou hast spoken truth: the case is as thou hast said, O faithful Wezeer: it is probable that this sage came as a spy to accomplish my death; and if he cured me by a thing I held in my hand, he may destroy me by a thing that I may smell: what then, O Wezeer, shall be done respecting him? The Wezeer answered, Send to him immediately, and desire him to come hither; and when he is come, strike off his head, and so shalt thou avert from thee his evil design, and be secure from him. Betray him before he betray thee.—The King said, Thou hast spoken right.

Immediately, therefore, he sent for the sage, who came, full of joy, not knowing what the Compassionate had decreed against him, and addressed the King with these words of the poet:—

If I fail any day to render thee due thanks, tell me for whom I have composed my verse and prose.

Thou hast loaded me with favours unsolicited, bestowed without delay on thy part, or excuse.

How then should I abstain from praising thee as thou deservest, and lauding thee both with my heart and voice? Nay, I will thank thee for thy benefits conferred upon me: they are light upon my tongue, though weighty to my back.

Knowest thou, said the King, wherefore I have summoned thee? The sage answered, None knoweth what is secret but God, whose name be exalted! Then said the King, I have summoned thee that I may take away thy life. The sage, in the utmost astonishment at this announcement, said, O King, wherefore wouldst thou kill me, and what offence hath been committed by me? The King answered, It hath been told me that thou art a spy, and that thou hast come hither to kill me: but I will prevent thee by killing thee first:—and so saying, he called out to the executioner, Strike off the head of this traitor, and relieve me from his wickedness,—Spare me, said the sage, and so may God spare thee; and destroy me not, lest God destroy thee.—And he repeated these words several times, like as I did, O ‘Efreet; but thou wouldst not let me go, desiring to destroy me.

King Yoonán then said to the sage Doobán, I shall not be secure unless I kill thee; for thou curedst me by a thing that I held in my hand, and I have no security against thy killing me by a thing that I may smell, or by some other means.—O King, said the sage, is this my recompense from thee? Dost thou return evil for good?—The King answered, Thou must be slain without delay. When the sage, therefore, was convinced that the King intended to put him to death, and that his fate was inevitable, he lamented the benefit that he had done to the undeserving. The executioner then advanced, and bandaged his eyes, and, having drawn his sword, said, Give permission. Upon this the sage wept, and said again, Spare me, and so may God spare thee; and destroy me not, lest God destroy thee! Wouldst thou return me the recompense of the crocodile?—What, said the King, is the story of the crocodile? The sage answered, I cannot relate it while in this condition; but I conjure thee by Allah to spare me, and so may He spare thee. And he wept bitterly. Then one of the chief officers of the King arose, and said, O King, give up to me the blood of this sage; for we have not seen him commit any offence against thee; nor have we seen him do aught but cure thee of thy disease, which wearied the other physicians and sages. The King answered, Ye know not the reason wherefore I would kill the sage: it is this, that if I suffered him to live, I should myself inevitably perish; for he who cured me of the disease under which I suffered by a thing that I held in my hand, may kill me by a thing that I may smell; and I fear that he would do so, and would receive an appointment on account of it; seeing that it is probable he is a spy who hath come hither to kill me; I must therefore kill him, and then shall I feel myself safe.—The sage then said again, Spare me, and so may God spare thee; and destroy me not, lest God destroy thee.

But he now felt certain, O ‘Efreet, that the King would put him to death, and that there was no escape for him; so he said, O King, if my death is indispensable, grant me some respite, that I may return to my house, and acquit myself of my duties, and give directions to my family and neighbours to bury me, and dispose of my medical books; and among my books is one of most especial value, which I offer as a present to thee, that thou mayest treasure it in thy library.—And what, said the King, is this book? He answered, It contains things not to be enumerated; and the smallest of the secret virtues that it possesses is this; that, when thou hast cut off my head, if thou open this book, and count three leaves, and then read three lines on the page to the left, the head will speak to thee, and answer whatever thou shalt ask. At this the King was excessively astonished, and shook with delight, and said to him, O Sage, when I have cut off thy head will it speak? He answered, Yes, O King; and this is a wonderful thing.

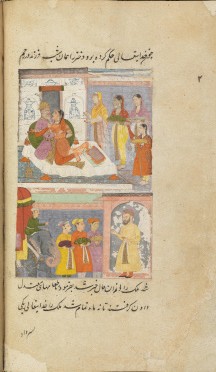

Image 6.9: The Story of Seyf ol-molûk and Badî`ol-Jamâl | This Indian manuscript with illustrations shares a common tale with The Thousand and One Nights.

Author: User “e-codices”

Source: Flickr

License: CC BY–NC

The King then sent him in the custody of guards; and the sage descended to his house, and settled all his affairs on that day; and on the following day he went up to the court: and the Emeers and Wezeers, and Chamberlains and Deputies, and all the great officers of the state, went thither also: and the court resembled a flower-garden. And when the sage had entered, he presented himself before the King, bearing an old book, and a small pot containing a powder: and he sat down, and said, Bring me a tray. So they brought him one; and he poured out the powder into it, and spread it. He then said, O King, take this book, and do nothing with it until thou hast cut off my head; and when thou hast done so, place it upon this tray, and order some one to press it down upon the powder; and when this is done, the blood will be stanched: then open the book. As soon as the sage had said this, the King gave orders to strike off his head; and it was done. The King then opened the book, and found that its leaves were stuck together; so he put his finger to his mouth, and moistened it with his spittle, and opened the first leaf, and the second, and the third; but the leaves were not opened without difficulty. He opened six leaves, and looked at them; but found upon them no writing. So he said, O Sage, there is nothing written in it. The head of the sage answered, Turn over more leaves. The King did so; and in a little while, the poison penetrated into his system; for the book was poisoned; and the King fell back, and cried out, The poison hath penetrated into me!—and upon this, the head of the sage Doobán repeated these verses:—

They made use of their power, and used it tyrannically;

and soon it became as though it never had existed.

Had they acted equitably, they had experienced equity; but

they oppressed; wherefore fortune oppressed them with

calamities and trials.

Thendidthecaseitselfannouncetothem,Thisisthe

reward of your conduct, and fortune is blameless.

And when the head of the sage Doobán had uttered these words, the King immediately fell down dead.

Continuation of the Story of the Fisherman