The Epic of Gilgamesh

Oral and written versions between ca. 2500-1400 B.C.E.

Sumer/Babylon

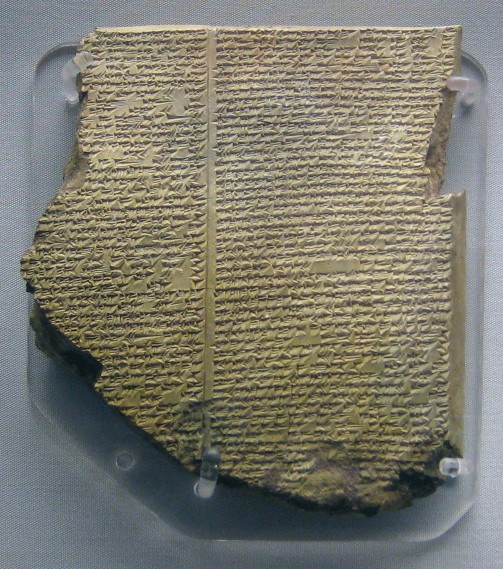

The story of Gilgamesh survives as the oldest epic in literature because it was preserved by rival societies in ancient Mesopotamia. The Sumerian story of this king of Uruk (modern day Warka in Iraq), who reigned around approximately 2700 B.C.E., was retold and rewritten by Babylonian, Assyrian, and Hittite scribes. The Standard Version, which modern scholars attribute to an Assyrian scribe/priest, combines many of the previous oral and written variants of the tale. The version of the epic presented here is a compilation of the Standard Version (which contains gaps where the tablets are damaged) and a variety of Assyrian, Babylonian, and Hittite versions that were discovered later. In the story, Gilgamesh (who is two-thirds divine and one-third human, a marvel of modern genetics) initially befriends Enkidu (also engineered by the gods) and then goes on a quest for immortality when he realizes that even semi-divine beings must die. Kept in the library of the Assyrian King Assurbanipal, the twelve clay tablets with the Standard Version were accidentally saved when, during the sack of Nineveh in 612 B.C.E., the walls of the library were caved in on the tablets. Archeologists discovered the eleventh tablet in the mid-1800s, which contains an account of the flood story that pre-dates the written version of the Biblical account of Noah, leading to the recovery of all twelve tablets, plus additional fragments. In 2003, in Warka, they found what is believed to be the tomb of Gilgamesh himself.

Sumerian/Babylonian Gods:

An (Babylonian: Anu): god of heaven; may have been the main god before 2500 B.C.E.

ninhursag (Babylonian: Aruru, Mammi): mother goddess; created the gods with An; assists in creation of man.

Enlil (Babylonian: Ellil): god of air; pantheon leader from 2500 B.C.E.; “father” of the gods because he is in charge (although An/Anu is actually the father of many of them); king of heaven & earth.

Enki (Babylonian: Ea): lord of the abyss and wisdom; god of water, creation, and fertility.

nanna (Babylonian: Sin): moon god.

Inanna (Babylonian: Ishtar): goddess of love, war, and fertility.

Utu (Babylonian: Shamash): god of the sun and justice.

ninlil (Babylonian: Mullitu, Mylitta): bride of Enlil.

Written by Laura J. Getty

Editor’s Note: I am combining two open access translations (one by R. Campbell Thompson and one by William Muss-Arnolt). I have made changes freely to those texts in the interests of readability: accepting many suggested additions, deleting others, altering word choice, adding some punctuation, and eliminating some of the more archaic language. By combining the two translations, the resulting text is as complete as I can make it at this point; the Thompson translation in particular draws on many fragments from Assyrian, Babylonian, and Hittite tablets that have been found after the Standard Version was discovered.

Edited by Laura J. Getty, University of North Georgia

The Epic of Gilgamesh

License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Translated by R. Campbell Thompson and William Muse Arnold

Compiled by Laura Getty

He who has discovered the heart of all matters, let him teach the nation;

He who all knowledge possesses should teach all the people;

He shall impart his wisdom, and so they shall share it together.

Gilgamesh—he was the Master of wisdom, with knowledge of all things;

He discovered concealed secrets, handed down a story of times before the flood,

Went on a journey far away, returned all weary and worn with his toiling,

Engraved on a table of stone his story.

He it was who built the ramparts of Uruk, the high-walled,

And he it was who set the foundation,

As solid as brass, of Eanna, the sacred temple of Anu and Ishtar,

Strengthened its base, its threshold….

Two-thirds of Gilgamesh are divine, and one-third of him human….

[The tablet then tells how Gilgamesh becomes king of Uruk. The death of the previous king creates panic in the city, described below.]

The she-asses have trampled down their foals;

The cows in madness turn upon their calves.

And as the cattle were frightened, so were the people.

Like the doves, the maidens sigh and mourn.

The gods of Uruk, the strong-walled,

Assume the shape of flies and buzz about the streets.

The protecting deities of Uruk, the strong-walled,

Take on the shape of mice and hurry into their holes.

Three years the enemy besieged the city of Uruk;

The city’s gates were barred, the bolts were shot.

And even Ishtar, the goddess, could not make headway against the enemy.

[Then Gilgamesh comes to the city as her savior, and later on appears as her king. He saves the city, but unfortunately his rule is tyrannical, and the people of Uruk complain to the gods.]

“You gods of heaven, and you, Anu,

Who brought my son into existence, save us!

He [Gilgamesh] has not a rival in all the land;

The shock of his weapons has no peer,

And cowed are the heroes of Uruk.

Your people now come to you for help.

Gilgamesh arrogantly leaves no son to his father,

Yet he should be the shepherd of the city.”

Day and night they poured out their complaint:

“He is the ruler of Uruk the strong-walled.

He is the ruler—strong, cunning—but

Gilgamesh does not leave a daughter to her mother,

Nor the maiden to the warrior, nor the wife to her husband.”

The gods of heaven heard their cry.

Anu gave ear, called the lady Aruru: “It was you, O Aruru,

Who made the first of mankind: create now a rival to him,

So that he can strive with him;

Let them fight together, and Uruk will be given relief.”

Upon hearing this Aruru created in her heart a man after the likeness of Anu.

Aruru washed her hands, took a bit of clay, and cast it on the ground.

Thus she created Enkidu, the hero, as if he were born of Ninurta (god of war and hunting).

His whole body was covered with hair; he had long hair on his head like a woman;

His flowing hair was luxuriant like that of the corn-god.

He ate herbs with the gazelles.

He quenched his thirst with the beasts.

He sported about with the creatures of the water.

Then did a hunter, a trapper, come face to face with this fellow,

Came on him one, two, three days, at the place where the beasts drank water.

But when he saw him the hunter’s face looked troubled

As he beheld Enkidu, and he returned to his home with his cattle.

He was sad, and moaned, and wailed;

His heart grew heavy, his face became clouded,

And sadness entered his mind.

The hunter opened his mouth and said, addressing his father:

“Father, there is a great fellow come forth from out of the mountains,

His strength is the greatest the length and breadth of the country,

Like to a double of Anu’s own self, his strength is enormous,

Ever he ranges at large over the mountains, and ever with cattle

Grazes on herbage and ever he sets his foot to the water,

So that I fear to approach him. The pits which I myself hollowed

With my own hands he has filled in again, and the traps that I set

Are torn up, and out of my clutches he has helped all the cattle escape,

And the beasts of the desert: to work at my fieldcraft, or hunt, he will not allow me.”

His father opened his mouth and said, addressing the hunter:

“Gilgamesh dwells in Uruk, my son, whom no one has vanquished,

It is his strength that is the greatest the length and breadth of the country,

Like to a double of Anu’s own self, his strength is enormous,

Go, set your face towards Uruk: and when he hears of a monster,

He will say ‘Go, O hunter, and take with you a courtesan-girl, a hetaera (a sacred temple girl from Eanna, the temple of Ishtar).

When he gathers the cattle again in their drinking place,

So shall she put off her mantle, the charm of her beauty revealing;

Then he shall see her, and in truth will embrace her, and thereafter his cattle,

With which he was reared, with straightaway forsake him.’”

Image 1.8: Gilgamesh Statue | This statue of Gilgamesh depicts him in his warrior’s outfit, holding a lion cub under one arm.

Author: User “zayzayem”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY-SA 2.0

The hunter listened to the advice of his father and straightaway

He went to Gilgamesh, taking the road towards Uruk.

To Gilgamesh he came, and addressed his speech to him, saying:

“There is a great fellow come forth from out of the mountains,

His strength is the greatest the length and breadth of the country,

Like to a double of Anu’s own self, his strength is enormous,

Ever he ranges at large over the mountains, and ever with cattle

Grazes on herbage and ever he sets his foot to the water,

So that I fear to approach him. The pits which I myself hollowed

With mine own hands he has filled in again, and the traps that I set

Are torn up, and out of my clutches he has helped all the cattle escape,

And the beasts of the desert: to work at my fieldcraft, or hunt, he will not allow me.”

Gilgamesh made this answer to the hunter:

“Go, O hunter, and take with you a courtesan-girl, a hetaera from Ishtar’s temple.

When he gathers the cattle again in their drinking place,

So shall she put off her mantle, the charm of her beauty revealing;

Then he shall see her, and in truth will embrace her, and thereafter his cattle,

With which he was reared, with straightaway forsake him.”

Forth went the hunter, took with him a courtesan-girl, a hetaera, the woman Shamhat;

Together they proceeded straightway, and

On the third day they reached the appointed field.

There the hunter and the hetaera rested.

One day, two days, they lurked at the entrance to the well,

Where the cattle were accustomed to slake their thirst,

Where the creatures of the waters were sporting.

Then came Enkidu, whose home was the mountains,

Who with gazelles ate herbs,

And with the cattle slaked his thirst,

And with the creatures of the waters rejoiced his heart.

And Shamhat beheld him.

“Behold, there he is,” the hunter exclaimed; “now reveal your body,

Uncover your nakedness, and let him enjoy your favors.

Be not ashamed, but yield to his sensuous lust.

He shall see you and shall approach you;

Remove your garment, and he shall lie in your arms;

Satisfy his desire after the manner of women;

Then his cattle, raised with him on the field, shall forsake him

While he firmly presses his breast on yours.”

And Shamhat revealed her body, uncovered her nakedness,

And let him enjoy her favors.

She was not ashamed, but yielded to his sensuous lust.

She removed her garment, he lay in her arms,

And she satisfied his desire after the manner of women.

He pressed his breast firmly upon hers.

For six days and seven nights Enkidu enjoyed the love of Shamhat.

And when he had sated himself with her charms,

He turned his face toward his cattle.

The gazelles, resting, beheld Enkidu; they and

The cattle of the field turned away from him.

This startled Enkidu and his body grew faint;

His knees became stiff, as his cattle departed,

And he became less agile than before.

And as he realized what had happened, he came to a decision.

He turned again, in love enthralled, to the feet of the temple girl,

And gazed up into the face of Shamhat.

And while she spoke, his ears listened attentively; And

Shmahat spoke to Enkidu and said:

“You are magnificant, Enkidu, you shall be like a god;

Why, then, do you lie down with the beasts of the field?

Come, I will take you to strong-walled Uruk;

To the glorious house, the dwelling of Anu and Ishtar,

The palace of Gilgamesh, the hero who is perfect in strength,

Surpassing, like a mountain bull, men in power.”

While she spoke this way to him, he listened to her wise speech.

And Enkidu spoke to her, the temple girl:

“Come then, Shamhat, take me, and lead me

To the glorious dwelling, the sacred seat of Anu and Ishtar,

To the palace of Gilgamesh, the hero who is perfect in strength,

Surpassing, like as a mountain bull, men in power. I will challenge him.”

Shamhat warned Enkidu, saying:

“You will see Gilgamesh.

I have seen his face; it glows with heroic courage.

Strength he possesses, magnificent is his whole body.

His power is stronger than yours.

He rests not nor tires, neither by day nor by night.

O Enkidu, change your intention.

Shamash loves Gilgamesh;

Anu and Ea are whispering wisdom into his ear.

Before you come down from the mountain

Gilgamesh will have seen you in a dream in Uruk.”

[Gilgamesh had a dream and was troubled because he could not interpret it.]

Gilgamesh came, to understand the dream, and said to his mother:

“My mother, I dreamed a dream in my nightly vision;

The stars of heaven, like Anu’s host, fell upon me.

Although I wrestled him, he was too strong for me, and even though I loosed his hold on me,

I was unable to shake him off of me: and now, all the meanwhile,

People from Uruk were standing around him.

My own companions were kissing his feet; and I to my breast like a woman did hold him,

Then I presented him low at your feet, that as my own equal you might recognize him.”

She who knows all wisdom answered her son;

“The stars of the heavens represent your comrades,

That which was like unto Anu’s own self, which fell on your shoulders,

Which you did wrestle, but he was too strong for you, even though you loosed his hold on you,

But you were unable to shake him off of you,

So you presented him low at my feet, that as your own equal

I might recognize him—and you to your breast like a woman did hold him:

This is a stout heart, a friend, one ready to stand by a comrade,

One whose strength is the greatest, the length and breadth of the country,

Like to a double of Anu’s own self, his strength is enormous.

Now, since you to your breast did hold him the way you would a woman,

This is a sign that you are the one he will never abandon:

This is the meaning of your dream.”

Again he spoke to his mother,

“Mother, a second dream did I see: Into Uruk, the high-walled,

Hurtled an axe, and they gathered about it:

People were standing about it, the people all thronging before it,

Artisans pressing behind it, while I at your feet did present it,

I held it to me like a woman, that you might recognize it as my own equal.”

She the all-wise, who knows all wisdom, thus answered her offspring:

“That axe you saw is a man; like a woman did you hold him,

Against your breast, that as your own equal I might recognize him;

This is a stout heart, a friend, one ready to stand by a comrade; He will never abandon you.”

[Meanwhile, Shamhat helps Enkidu adjust to living among humans.]

Then Shamhat spoke to Enkidu:

“As I view you, even like a god, O Enkidu, you are,

Why with the beasts of the field did you ever roam through the wilderness?

I’ll lead you to Uruk broad-marketed, yes, to the Temple

Sacred, the dwelling of Anu—O Enkidu, come, so that I may guide you,

To Eanna, the dwelling of Anu, where Gilgamesh lives,

He, the supreme of creation; and you will embrace him,

And even as yourself you shall love him.

O, get up from the ground—which is a shepherd’s bed only.”

He heard what she said, welcomed her advice: the advice of the woman struck home.

She took off one length of cloth wherewith she might clothe him: the other she herself wore,

And so, holding his hand like a brother, she led him

To the huts of the shepherds, the place of the sheepfolds. The shepherds

Gathered at the sight of him.

He in the past was accustomed to suck the milk of the wild things!

Bread which she set before him he broke, but he gazed and he stared:

Enkidu did not know how to eat bread, nor had he the knowledge to drink mead!

Then the woman made answer, to Enkidu speaking,

“Enkidu, taste of the bread, for it is life; in truth, the essential of life;

Drink also of the mead, which is the custom of the country.”

Enkidu ate the bread, ate until he was gorged,

Drank of the mead seven cups; his spirits rose, and he was exultant,

Glad was his heart, and cheerful his face:

He anointed himself with oil: and thus became human.

He put on a garment to be like a man and taking his weapons,

He hunted the lions, which harried the shepherds all the nights, and he caught the jackals.

He, having mastered the lions, let the shepherds sleep soundly.

Enkidu—he was their guardian—became a man of full vigor.

Enkidu saw a man passing by, and when he observed the fellow,

He said to the woman: “Shamhat, bring me this fellow,

Where is he going? I would know his intention.”

Shamhat called to the man to come to them, asking: “O, what are you seeking, Sir?”

The man spoke, addressing them:

“I am going, then, to heap up the offerings such as are due to the city of Uruk;

Come with me, and on behalf of the common good bring in the food of the city.

You will see Gilgamesh, king of broad-marketed Uruk;

After the wedding, he sleeps first with the bride, his birthright, before the husband.”

So, at the words of the fellow, they went with him to Uruk.

Enkidu, going in front with the temple girl coming behind him,

Entered broad-marketed Uruk; the populace gathered behind him,

Then, as he stopped in the street of broad-marketed Uruk, the people

Thronging behind him exclaimed “Of a truth, like to Gilgamesh is he,

Shorter in stature, but his composition is stronger.”

Strewn is the couch for the love-rites, and Gilgamesh now in the night-time

Comes to sleep, to delight in the woman, but Enkidu, standing

There in the street, blocks the passage to Gilgamesh, threatening

Gilgamesh with his strength.

Gilgamesh shows his rage, and he rushed to attack him: they met in the street.

Enkidu barred up the door with his foot, and to Gilgamesh denied entry.

They grappled and snorted like bulls, and the threshold of the door

Shattered: the very wall quivered as Gilgamesh with Enkidu grappled and wrestled.

Gilgamesh bent his leg to the ground [pinning Enkidu]: so his fury abated,

And his anger was quelled: Enkidu thus to Gilgamesh spoke:

“Of a truth, did your mother (Ninsun, the wild cow goddess) bear you,

And only you: that choicest cow of the steer-folds,

Ninsun exalted you above all heroes, and Enlil has given

You the kingship over men.”

[The next part of the story is lost on a broken part of the tablet. When the story resumes, time has passed, and Gilgamesh and Enkidu are now friends. Enkidu is grieving the loss of a woman: possibly Shamhat leaving him, possibly another woman who has died.]

Enkidu there as he stood listened to Gilgamesh’s words, grieving,

Sitting in sorrow: his eyes filled with tears, and his arms lost their power,

His body had lost its strength. Each clasped the hand of the other.

Holding on to each other like brothers, and Enkidu answered Gilgamesh:

“Friend, my darling has circled her arms around my neck to say goodbye,

Which is why my arms lose their power, my body has lost its strength.”

[Gilgamesh decides to distract his friend with a quest.]

Gilgamesh opened his mouth, and to Enkidu he spoke in this way:

“I, my friend, am determined to go to the Forest of Cedars,

Humbaba the Fierce lives there, I will overcome and destroy what is evil,

Then will I cut down the Cedar trees.”

Enkidu opened his mouth, and to Gilgamesh he spoke in this way,

“Know, then, my friend, that when I was roaming with the animals in the mountains

I marched for a distance of two hours from the skirts of the Forest

Into its depths. Humbaba—his roar was a whirlwind,

Flame in his jaws, and his very breath Death! O, why have you desired

To accomplish this? To meet with Humbaba would be an unequal conflict.”

Gilgamesh opened his mouth and to Enkidu he spoke in this way:

“It is because I need the rich resources of its mountains that I go to the Forest.”

Enkidu opened his mouth and to Gilgamesh he spoke in this way:

“But when we go to the Forest of Cedars, you will find that its guard is a fighter,

Strong, never sleeping. O Gilgamesh,

So that he can safeguard the Forest of Cedars, making it a terror to mortals,

Enlil has appointed him—Humbaba, his roar is a whirlwind,

Flame in his jaws, and his very breath Death! Yes, if he hears but a tread in the Forest,

Hears but a tread on the road, he roars—‘Who is this come down to his Forest?’

And terrible consequences will seize him who comes down to his Forest.”

Gilgamesh opened his mouth and to Enkidu he spoke in this way:

“Who, O my friend, is unconquered by death? A god, certainly,

Lives forever in the daylight, but mortals—their days are all numbered,

All that they do is but wind—But since you are now dreading death,

Offering nothing of your courage—I, I’ll be your protector, marching in front of you!

Your own mouth shall tell others that you feared the onslaught of battle,

Whereas I, if I should fall, will have established my name forever.

It was Gilgamesh who fought with Humbaba, the Fierce!

In the future, after my children are born to my house, and climb up into your lap, saying:

‘Tell us all that you know,’ [what shall you say]?

When you talk this way, you make me long for the Cedars even more;

I am determined to cut them down, so that I may gain fame everlasting.”

Gilgamesh spoke again to Enkidu, saying:

“Now, O my friend, I must give my orders to the craftsmen,

So that they cast in our presence our weapons.”

They delivered the orders to the craftsmen: the mold did the workmen prepare, and the axes

Monstrous they cast: yes, the axes did they cast, each weighing three talents;

Glaives, too, monstrous they cast, with hilts each weighing two talents,

Blades, thirty manas to each, corresponding to fit them: the inlay,

Gold thirty manas each sword: so were Gilgamesh and Enkidu laden

Each with ten talents of weight.

And now in the Seven Bolt Portal of Uruk

Hearing the noise did the artisans gather, assembled the people,

There in the streets of broad-marketed Uruk, in Gilgamesh’s honor,

So did the Elders of Uruk the broad-marketed take seat before him.

Gilgamesh spoke thus: “O Elders of Uruk the broad-marketed, hear me!

I go against Humbaba, the Fierce, who shall say, when he hears that I am coming,

‘Ah, let me look on this Gilgamesh, he of whom people are speaking,

He with whose fame the countries are filled’—’Then I will overwhelm him,

There in the Forest of Cedars—I’ll make the land hear it,

How like a giant the hero of Uruk is—yes, for I am determined to cut down the Cedars

So that I may gain fame everlasting.”

To Gilgamesh the Elders of Uruk the broad-marketed gave this answer:

“Gilgamesh, it is because you are young that your valor makes you too confident,

Nor do you know to the full what you seek to accomplish.

News has come to our ears of Humbaba, who is twice the size of a man.

Who of free will then would seek to oppose him or encounter his weapons?

Who would march for two hours from the skirts of the Forest

Into its depths? Humbaba, his roar is a whirlwind,

Flame is in his jaws, and his very breath is Death! O, why have you desired to accomplish this?

To fight with Humbaba would be an unequal conflict.”

Gilgamesh listened to the advice of his counselors and pondered,

Then cried out to his friend: “Now, indeed, O my friend, will I voice my opinion.

In truth, I dread him, and yet into the depths of the Forest I will go.”

And the Elders spoke:

“Gilgamesh, put not your faith in the strength of your own person solely,

And do not trust your fighting skills too much.

Truly, he who walks in front is able to safeguard a comrade,

Your guide will guard you; so, let Enkidu walk in front of you,

For he knows the road to the Forest of Cedars;

He lusts for battle, and threatens combat.

Enkidu—he would watch over a friend, would safeguard a comrade, Yes,

such a man would deliver his friend from out of the pitfalls.

We, O King, in our conclave have paid close attention to your welfare;

You, O King, shall pay attention to us in return.”

Gilgamesh opened his mouth and spoke to Enkidu, saying:

“To the Palace of Splendor, O friend, come, let us go,

To the presence of Ninsun, the glorious Queen, yes, to Ninsun,

Wisest of all clever women, all-knowing; she will tell us how to proceed.”

They joined hands and went to the Palace of Splendor,

Gilgamesh and Enkidu. To the glorious Queen, yes, to Ninsun

Gilgamesh came, and he entered into her presence:

“Ninsun, I want you to know that I am going on a long journey,

To the home of Humbaba to encounter a threat that is unknown,

To follow a road which I know not, which will be new from the time of my starting,

Until my return, until I arrive at the Forest of Cedars,

Until I overthrow Humbaba, the Fierce, and destroy him.

The Sun god abhors all evil things, Shamash hates evil; Ask him to help us.”

So Ninsun listened to her offspring, to Gilgamesh,

Entered her chamber and decked herself with the flowers of Tulal,

Put the festival clothes on her body,

Put on the festival adornments of her bosom, her head with a circlet crowned,

Climbed the stairway, ascended to the roof, and the parapet mounted,

Offered her incense to Shamash, her sacrifice offered to Shamash,

Then towards Shamash she lifted her hands in prayer, saying:

“Why did you give this restlessness of spirit to Gilgamesh, my son?

You gave him restlessness, and now he wants to go on a long journey

To where Humbaba dwells, to encounter a threat that is unknown,

To follow a road which he knows not, which will be new from the time of his starting,

Until his return, until he arrives at the Forest of Cedars,

Until he overthrows Humbaba, the Fierce, and destroys him.

You abhor all evil things; you hate evil. Remember my son when that day comes,

When he faces Humbaba. May Aya, your bride, remind you of my son.”

Now Gilgamesh knelt before Shamash, to utter a prayer; tears streamed down his face:

“Here I present myself, Shamash, to lift up my hands in entreaty

That my life may be spared; bring me again to the ramparts of Uruk:

Give me your protection. I will give you homage.”

And Shamash made answer, speaking through his oracle.

[Although the next lines are missing, Shamash evidently gives his permission, so Gilgamesh and Enkidu get ready for their journey.]

The artisans brought monstrous axes, they delivered the bow and the quiver

Into his hand; so, taking an ax, he slung on his quiver,

He fastened his glaive to his baldrick.

But before the two of them set forth on their journey, they offered

Gifts to the Sun god, that he might bring them home to Uruk in safety.

Now the Elders give their blessings, to Gilgamesh giving

Counsel concerning the road: “O Gilgamesh, do not trust to your own power alone,

Guard yourself; let Enkidu walk in front of you for protection.

He is the one who discovered the way, the road he has traveled.

Truly, all the paths of the Forest are under the watchful eye of Humbaba.

May the Sun god grant you success to attain your ambition,

May he level the path that is blocked, cleave a road through the forest for you to walk.

May the god Lugalbanda bring dreams to you, ones that shall make you glad,

So that they help you achieve your purpose, for like a boy

You have fixed your mind to the overthrow of Humbaba.

When you stop for the night, dig a well, so that the water in your skin-bottle

Will be pure, will be cool;

Pour out an offering of water to the Sun god, and do not forget Lugalbanda.”

Gilgamesh drew his mantle around his shoulders,

And they set forth together on the road to Humbaba.

Every forty leagues they took a meal;

Every sixty leagues they took a rest.

Gilgamesh walked to the summit and poured out his offering for the mountain:

“Mountain, grant me a dream.”

The mountain granted him a dream. . .

Then a chill gust of wind made him sway like the corn of the mountains;

Straightaway, sleep that flows on man descended upon him: at midnight

He suddenly ended his slumber and hurried to speak to his comrade:

“Didn’t you call me, O friend? Why am I awakened from slumber?

Didn’t you touch me—or has some spirit passed by me? Why do I tremble?”

[Gilgamesh’s dream is terrifying, but Enkidu interprets it to mean that Shamash will help them defeat Humbaba. This process is repeated several times. Eventually, they arrive at the huge gate that guards the Cedar Forest.]

Enkidu lifted his eyes and spoke to the Gate as if it were human:

“O Gate of the Forest, I for the last forty leagues have admired your wonderful timber,

Your wood has no peer in other countries;

Six gar your height, and two gar your breadth . . .

O, if I had but known, O Gate, of your grandeur,

Then I would lift an ax…[basically, I would have brought a bigger ax].

[The heroes force the gate open.]

They stood and stared at the Forest, they gazed at the height of the Cedars,

Scanning the paths into the Forest: and where Humbaba walked

Was a path: paths were laid out and well kept.

They saw the cedar hill, the dwelling of gods, the sanctuary of Ishtar.

In front of the hill a cedar stood of great splendor,

Fine and good was its shade, filling the heart with gladness.

[From his words below, Humbaba must have taunted the heroes at this point, and Gilgamesh is preparing to attack Humbaba.]

The Sung god saw Gilgamesh through the branches of the Cedar trees:

Gilgamesh prayed to the Sun god for help.

The Sun god heard the entreaty of Gilgamesh,

And against Humbaba he raised mighty winds: yes, a great wind,

Wind from the North, a wind from the South, a tempest and storm wind,

Chill wind, and whirlwind, a wind of all harm: eight winds he raised,

Seizing Humbaba from the front and the back, so that he could not go forwards,

Nor was he able to go back: and then Humbaba surrendered.

Humbaba spoke to Gilgamesh this way: “O Gilgamesh, I pray you,

Stay now your hand: be now my master, and I’ll be your henchman:

Disregard all the words which I spoke so boastfully against you.”

Then Enkidu spoke to Gilgamesh: “Of the advice which Humbaba

Gives to you—you cannot risk accepting it.

Humbaba must not remain alive.”

[The section where they debate what to do is missing, but several versions have the end result.]

They cut off the head of Humbaba and left the corpse to be devoured by vultures.

[They return to Uruk after cutting down quite a few cedar trees.]

Gilgamesh cleansed his weapons, he polished his arms.

He took off the armor that was upon him. He put away

His soiled garments and put on clean clothes;

He covered himself with his ornaments, put on his baldrick.

Gilgamesh placed upon his head the crown.

To win the favor and love of Gilgamesh, Ishtar, the lofty goddess, desired him and said:

“Come, Gilgamesh, be my spouse,

Give, O give to me your manly strength.

Be my husband, let me be your wife,

And I will set you in a chariot embossed with precious stones and gold,

With wheels made of gold, and shafts of sapphires.

Large kudanu-lions you shall harness to it.

Under sweet-smelling cedars you shall enter into our house.

And when you enter into our house

You shall sit upon a lofty throne, and people shall kiss your feet;

Kings and lords and rulers shall bow down before you.

Whatever the mountain and the countryside produces, they shall bring to you as tribute.

Your sheep shall bear twin-ewes.

You shall sit upon a chariot that is splendid,

drawn by a team that has no equal.”

Gilgamesh opened his mouth in reply, said to Lady Ishtar:

“Yes, but what could I give you, if I should take you in marriage?

I could provide you with oils for your body, and clothing: also,

I could give you bread and other foods: there must be enough sustenance

Fit for divinity—I, too, must give you a drink fit for royalty.

What, then, will be my advantage, supposing I take you in marriage?

You are but a ruin that gives no shelter to man from the weather,

You are but a back door that gives no resistance to blast or to windstorm,

You are but a palace that collapses on the heroes within it,

You are but a pitfall with a covering that gives way treacherously,

You are but pitch that defiles the man who carries it,

You are but a bottle that leaks on him who carries it,

You are but limestone that lets stone ramparts fall crumbling in ruin.

You are but a sandal that causes its owner to trip.

Who was the husband you faithfully loved for all time?

Who was your lord who gained the advantage over you?

Come, and I will tell you the endless tale of your husbands.

Where is your husband Tammuz, who was to be forever?

Well, I will tell you plainly the dire result of your behavior.

To Tammuz, the husband of your youth,

You caused weeping and brought grief upon him every year.

[She sent Tammuz to the Underworld in her place, not telling him that he would only be able to return in the spring, like Persephone/Proserpina.]

The allallu-bird, so bright of colors, you loved;

But its wing you broke and crushed,

so that now it sits in the woods crying: ‘O my wing!’

You also loved a lion, powerful in his strength;

Seven and seven times did you dig a snaring pit for him.

You also loved a horse, pre-eminent in battle,

But with bridle, spur, and whip you forced it on,

Forced it to run seven double-leagues at a stretch.

And when it was tired and wanted to drink, you still forced it on,

Causing weeping and grief to its mother, Si-li-li.

You also loved a shepherd of the flock

Who continually poured out incense before you,

And who, for your pleasure, slaughtered lambs day by day.

You smote him, and turned him into a tiger,

So that his own sheep-boys drove him away,

And his own dogs tore him to pieces.

You also loved a gardener of your father,

Who continually brought you delicacies,

And daily adorned your table for you.

You cast your eye on him, saying:

‘O Ishullanu of mine, come, let me taste of your vigor,

Let us enjoy your manhood.’

But he, Ishullanu, said to you ‘What are you asking of me?

I have only eaten what my mother has baked, [he is pure]

And what you would give me would be bread of transgression, [she is not]

Yes, and iniquity! Furthermore, when are thin reeds a cloak against winter?’

You heard his answer and smote him and make him a spider,

Making him lodge midway up the wall of a dwelling—not to move upwards

In case there might be water draining from the roof; nor down, to avoid being crushed.

So, too, would you love me and then treat me like them.”

When Ishtar heard such words, she became enraged, and went up into heaven,

and came unto Anu [her father], and to Antum [her mother] she went, and spoke to them:

“My father, Gilgamesh has insulted me;

Gilgamesh has upbraided me with my evil deeds,

My deeds of evil and of violence.”

And Anu opened his mouth and spoke—

Said unto her, the mighty goddess Ishtar:

“You asked him to grant you the fruit of his body;

Therefore, he told you the tale of your deeds of evil and violence.”

Ishtar said to Anu, her father:

“Father, O make me a Heavenly Bull, which shall defeat Gilgamesh,

Fill its body with flame . . . .

But if you will not make this Bull…

I will smite [the gates of the Underworld], break it down and release the ghosts,

Who shall then be more numerous than the living:

More than the living will be the dead.”

Anu answered Ishtar, the Lady:

“If I create the Heavenly Bull, for which you ask me,

Then seven years of famine will follow after his attack.

Have you gathered corn enough, and enough fodder for the cattle?”

Ishtar made answer, saying to Anu, her father:

“Corn for mankind have I hoarded, have grown fodder for the cattle.”

[After this a hundred men attack the Bull, but with his fiery breath he annihilates them. Two hundred men then attack the Bull with the same result, and then three hundred more are overcome.]

Enkidu girded his middle; and straightway Enkidu, leaping,

Seized the Heavenly Bull by his horns, and headlong before him

Cast down the Heavenly Bull his full length.

[On an old Babylonian cylinder that depicts the fight, we see the Heavenly Bull standing on its hind feet, Enkidu holding the monster by its head and tail, while Gilgamesh plunges the dagger into its heart.]

Then Ishtar went up to the wall of Uruk, the strong-walled;

She uttered a piercing cry and broke out into a curse, saying:

“Woe to Gilgamesh, who thus has grieved me, and has killed the Heavenly Bull.”

But Enkidu, hearing these words of Ishtar, tore out the right side of the Heavenly Bull,

And threw it into her face, saying:

“I would do to you what I have done to him;

Truly, I would hang the entrails on you like a girdle.”

Then Ishtar gathered her followers, the temple girls,

The hierodules, and the sacred prostitutes.

Over the right side of the Heavenly Bull she wept and lamented.

But Gilgamesh assembled the people, and all his workmen.

The workmen admired the size of its horns.

Thirty minas of precious stones was their value;

Half of an inch in size was their thickness. Six measures of oil they both could hold.

He dedicated it for the anointing of his god Lugalbanda.

He brought the horns and hung them up in the shrine of his lordship.

Then they washed their hands in the river Euphrates,

Took the road, and set out for the city,

And rode through the streets of the city of Uruk.

The people of Uruk assembled and looked with astonishment at the heroes.

Gilgamesh then spoke to the servants of his palace

And cried out to them, saying: “Who is the most glorious among the heroes?

Who shines among the men?” “Gilgamesh is the most glorious among the heroes,

Gilgamesh shines among the men!”

And Gilgamesh held a joyful feast in his palace. Then the heroes slept on their couches.

And Enkidu slept, and saw a vision in his sleep. He arose and spoke to Gilgamesh in this way:

“My friend, why have the great gods sat in counsel?

Gilgamesh, hear the dream which I saw in the night: said Enlil, Ea, and the Sun-god of heaven,

‘They have killed the Heavenly Bull and smote Humbaba, who guarded the cedars.’ Enlil said: ‘Enkidu shall die: but Gilgamesh shall not die. O Sun god, you helped them slay the Heavenly Bull and Humbaba. But now Enkidu shall die. Did you think it right to help them? You move among them like a mortal [although you are a god].’”

[The gods give Enkidu a fever. Enkidu curses the temple girl for bringing him to Uruk.]

“O hetaera, I will decree a terrible fate for you—your woes shall never end for all eternity. Come, I will curse thee with a bitter curse: may there never be satisfaction of your desires—and may disaster befall your house, may the gutters of the street be your dwelling, may the shade of the wall be your abode—may scorching heat and thirst destroy your strength.”

The Sun god heard him, and opened his mouth, and from out of the heavens

He called him: “O Enkidu, why do you curse the hetaera?

It was she who made you eat bread fit for the gods: yes, wine too,

She made you drink, fit for royalty: a generous mantle

She put on you, and she gave you Gilgamesh, a splendid comrade.

He will give you a magnificent funeral,

So that the gods of the Underworld will kiss your feet in their homage;

He, too, will make all the people of Uruk lament in your honor,

Making them mourn you, and damsels and heroes weep at your funeral,

While he himself for your sake will cover himself in dust,

And he will put on the skin of a lion and range over the desert.”

Enkidu listened to the words of the valiant Shamash,

And when the Sun god finished speaking, Enkidu’s wrath was appeased.

“Hetaera, I call back my curse, and I will restore you to your place with blessings!

May monarchs and princes and chiefs fall in love with you;

And for you may the hero comb out his locks; whoever would embrace you,

Let him open his money pouch, and let your bed be azure and golden;

May he entreat you kindly, let him heap treasure before you;

May you enter into the presence of the gods;

May you be the mother of seven brides.”

Enkidu said to Gilgamesh:

“Friend, a dream I have seen in my night-time: the sky was thundering,

It echoed over the earth, and I by myself was standing,

When I perceived a man, all dark was his face,

And his nails were like the claws of a lion.

He overcome me, pressed me down, and he seized me,

He led me to the Dwelling of Darkness, the home of Ereshkigal, Queen of the Underworld,

To the Dwelling from which he who enters it never comes forth!

By the road on which there can be no returning,

To the Dwelling whose tenants are always bereft of the daylight,

Where for their food is the dust, and the mud is their sustenance: bird-like,

They wear a garment of feathers: and, sitting there in the darkness,

Never see the light.

Those who had worn crowns, who of old ruled over the country,

They were the servants of Anu and Enlil who carried in the food,

Served cool water from the skins. When I entered

Into this House of the Dust, High Priest and acolyte were sitting there,

Seer and magician, the priest who the Sea of the great gods anointed,

Here sat Etana the hero, the Queen of the Underworld also,

Ereshkigal, in whose presence sat the Scribe of the Underworld,

Belit-seri, and read before her; she lifted her head and beheld me [and I awoke in terror].”

And there lay Enkidu for twelve days; for twelve days he lay on his couch before he died.

Gilgamesh wept bitterly over the loss of his friend, and he lay on the ground, saying:

“I am not dying, but weeping has entered into my heart;

Fear of death has befallen me, and I lie here stretched out upon the ground.

Listen to me, O Elders; I weep for my comrade Enkidu,

Bitterly crying like a wailing woman: my grip is slackened on my ax,

For I have been assailed by sorrow and cast down in affliction.”

“Comrade and henchman, Enkidu—what is this slumber that has overcome you?

Why are your eyes dark, why can you not hear me?”

But he did not raise his eyes, and his heart, when Gilgamesh felt it, made no beat.

Then he covered his friend with a veil like a bride;

Lifted his voice like a lion,

Roared like a lioness robbed of her whelps. In front of his comrade

He paced backwards and forwards, tearing his hair and casting away his finery,

Plucking and casting away all the grace of his person.

Then when morning began to dawn, Gilgamesh said:

“Friend, I will give you a magnificent funeral,

So that the gods of the Underworld will kiss your feet in their homage;

I will make all the people of Uruk lament in your honor,

Making them mourn you, and damsels and heroes weep at your funeral,

While I myself for your sake will cover myself in dust,

And I will put on the skin of a lion and range over the desert.”

Gilgamesh brought out also a mighty platter of wood from the highlands.

He filled a bowl of bright ruby with honey; a bowl too of azure

He filled with cream, for the gods.

Gilgamesh wept bitterly for his comrade, for Enkidu, ranging

Over the desert: “I, too—shall I not die like Enkidu also?

Sorrow hath entered my heart; I fear death as I range over the desert,

So I will take the road to the presence of Utnapishtim, the offspring of Ubara-Tutu;

And with speed will I travel.”

In darkness he arrived at the Gates of the Mountains,

And he met with lions, terror falling on him; he lifted his head skywards,

Offered his prayer to the Moon god, Sin:

“O deliver me!” He took his ax in his hand and drew his glaive from his baldric,

He leapt among them, smiting and crushing, and they were defeated.

As he reached the Mountains of Mashu,

Where every day they keep watch over the Sun god’s rising and setting,

The peaks rise up to the Zenith of Heaven, and downwards

Deep into the Underworld reach their roots: and there at their portals stand sentry

Scorpion-men, awful in terror, their very glance Death: and tremendous,

Shaking the hills, their magnificence; they are the Wardens of Shamash,

Both at his rising and setting. No sooner did Gilgamesh see them

Than from alarm and dismay was his face stricken with pallor,

Senseless, he groveled before them.

Then to his wife spoke the Scorpion:

“Look, he that comes to us—his body is the flesh of the gods.”

Then his wife answered to the Scorpion-man: “Two parts of him are god-like;

One third of him is human.”

[Gilgamesh explains why he is searching for Utnapishtim; it is a journey that no one else has ever taken, but the Scorpion-Man agrees to let him take the Road of the Sun—a tunnel that passes through the mountain. For twenty four hours, Gilgamesh travels in darkness, emerging into the Garden of the Gods, filled with fruit trees. Shamash enters the garden, and he is surprised to see Gilgamesh—or any human—in the garden.]

“This man is wearing the pelts of wild animals, and he has eaten their flesh.

This is Gilgamesh, who has crossed over to where no man has been”

Shamash was touched with compassion, summoning Gilgamesh and saying:

“Gilgamesh, why do you run so far, since the life that you seek

You shall not find?” Whereupon Gilgamesh answered the Sun god, Shamash:

“Shall I, after I roam up and down over the wastelands as a wanderer,

Lay my head in the bowels of the earth, and throughout the years slumber

Forever? Let my eyes see the Sun and be sated with brightness,

Yes, the darkness is banished far away, if there is enough brightness.

When will the man who is dead ever again look on the light of the Sunshine?”

[Shamash lets him continue on his quest, although the Sun god has said already that humans cannot escape mortality. He approaches the house of Siduri, a winemaker, whose location beyond Mount Mashu would suggest that the gods must be among her customers.]

Siduri, the maker of wine, wine was her trade; she was covered with a veil.

Gilgamesh wandered towards her, covered in pelts.

He possessed the flesh of the gods, but woe was in his belly,

Yes, and his face like a man who has gone on a far journey.

The maker of wine saw him in the distance, and she wondered,

She said in thought to herself: “This is one who would ravish a woman;

Why does he come this way?” As soon as the Wine-maker saw him,

She barred the gate, barred the house door, barred her chamber door, and climbed to the terrace.

Straight away Gilgamesh heard the sound of her shutting up the house,

Lifted his chin, and so did he let his attention fall on her.

Gilgamesh spoke to her, to the Wine-maker, saying:

“Wine-maker, what did you see, that you barred the gate,

Barred the house door, barred your chamber door? I will smite your gate,

Breaking the bolt.”

The Wine-maker, speaking to Gilgamesh, answered him, saying:

“Why is your vigor so wasted, why is your face sunken,

Why does your spirit have such sorrow, and why has your cheerfulness ceased?

O, but there’s woe in your belly! Like one who has gone on a far journey

Is your face—O, with cold and with heat is your face weathered,

Like a man who has ranged over the desert.”

Gilgamesh answered the Wine-maker, saying:

“Wine-maker, it is not that my vigor is wasted, nor that my face is sunken,

Nor that my spirit has sorrow, nor that my cheerfulness has ceased,

No, it is not that there is woe in my belly, nor that my face is like one

Who has gone on a far journey—nor is my face weathered

Either by cold or by heat as I range over the desert.

Enkidu—together we overcame all obstacles, ascending the mountains,

Captured the Heavenly Bull, and destroyed him: we overthrew Humbaba,

He whose abode was in the Forest of Cedars; we slaughtered the lions

There in the mountain passes; with me enduring all hardships,

Enkidu, he was my comrade—and his fate has overtaken him.

I mourned him six days, until his burial; only then could I bury him.

I dreaded Death, so that I now range over the desert: the fate of my comrade

Lay heavy on me—O, how do I give voice to what I feel?

For the comrade I have so loved has become like dust,

He whom I loved has become like the dust—I, shall I not, also,

Lay me down like him, throughout all eternity never to return?”

The Wine-maker answered Gilgamesh:

“Gilgamesh, why do you run so far, since the life that you seek

You shall not find? For the gods, in their creation of mortals,

Allotted Death to man, but Life they retained in their keeping.

Gilgamesh, fill your belly with food,

Each day and night be merry, and make every day a holiday,

Each day and night dance and rejoice; wear clean clothes,

Yes, let your head be washed clean, and bathe yourself in the water,

Cherish the little one holding your hand; hold your spouse close to you and be happy,

For this is what is given to mankind.

Gilgamesh continued his speech to the Wine-maker, saying:

“Tell me, then, Wine-maker, which is the way to Utnapishtim?

If it is possible, I will even cross the Ocean itself,

But if it is impossible, then I will range over the desert.”

In this way did the Wine-maker answer him, saying:

“There has never been a crossing, O Gilgamesh: never before

Has anyone, coming this far, been able to cross the Ocean:

Shamash crosses it, of course, but who besides Shamash

Makes the crossing? Rough is the passage,

And deep are the Waters of Death when you reach them.

Gilgamesh, if by chance you succeed in crossing the Ocean,

What will you do, when you arrive at the Waters of Death?

Gilgamesh, there is a man called Urshanabi, boatman to Utnapishtim,

He has the urnu for the crossing,

Now go to him, and if it is possible to cross with him

Then cross—but if it is not possible, then retrace your steps homewards.”

Gilgamesh, hearing this, took his ax in his hand and went to see Urshanabi.

[Evidently, Gilgamesh is not thinking too clearly, since he displays his strength to Urshanabi by destroying the sails of the boat. Urshanabi is not entirely impressed.]

Then Urshanabi spoke to Gilgamesh, saying:

“Tell to me what is your name, for I am Urshanabi, henchman,

Of far-off Utnapishtim.” Gilgamesh answered:

“Gilgamesh is my name, come hither from Uruk,

One who has traversed the Mountains, a wearisome journey of Sunrise,

Now that I have looked on your face, Urshanabi—let me see Utnapishtim,

The Distant one!”

Urshanabi spoke to Gilgamesh, saying:

“Why is your vigor so wasted, why is your face sunken,

Why does your spirit have such sorrow, and why has your cheerfulness ceased?

O, but there’s woe in your belly! Like one who has gone on a far journey

Is your face—O, with cold and with heat is your face weathered,

Like a man who has ranged over the desert.”

Gilgamesh answered, “It is not that my vigor is wasted, nor that my face is sunken,

Nor that my spirit has sorrow, nor that my cheerfulness has ceased,

No, it is not that there is woe in my belly, nor that my face is like one

Who has gone on a far journey—nor is my face weathered

Either by cold or by heat as I range over the desert.

Enkidu—together we overcame all obstacles, ascending the mountains,

Captured the Heavenly Bull, and destroyed him: we overthrew Humbaba,

He whose abode was in the Forest of Cedars; we slaughtered the lions

There in the mountain passes; with me enduring all hardships,

Enkidu, he was my comrade—and his fate has overtaken him.

I mourned him six days, until his burial; only then could I bury him.

I dreaded Death, so that I now range over the desert: the fate of my comrade

Lay heavily on me—O, how do I give voice to what I feel?

For the comrade I have so loved has become like dust,

He whom I loved has become like the dust—I, shall I not, also,

Lay me down like him, throughout all eternity never to return?”

Gilgamesh continued his speech to Urshanabi, saying:

“Please tell me, Urshanabi, which is the way to Utnapishtim?

If it is possible, I will even cross the Ocean itself,

But if it is impossible, then I will range over the desert.”

Urshanabi spoke to Gilgamesh, saying:

“Gilgamesh, your own hand has hindered your crossing of the Ocean,

You have destroyed the sails and destroyed the urnu.

Gilgamesh, take your axe in your hand; descend to the forest,

Fashion one hundred twenty poles each of five gar in length; make knobs of bitumen,

Sockets, too, add those to the poles: bring them to me.” When Gilgamesh heard this,

He took the ax in his hand, and the glaive drew forth from his baldric,

Went to the forest, and poles each of five gar in length did he fashion,

Knobs of bitumen he made, and he added sockets to the poles: and brought them to Urshanabi;

Gilgamesh and Urshanabi then set forth in their vessel,

They launched the boat on the swell of the wave, and they themselves embarked.

In three days they traveled the distance of a month and a half journey,

And Urshanabi saw that they had arrived at the Waters of Death.

Urshanabi said to Gilgamesh:

“Gilgamesh, take the first pole, thrust it into the water and push the vessel along,

But do not let the Waters of Death touch your hand.

Gilgamesh, take a second, a third, and a fourth pole,

Gilgamesh, take a fifth, a sixth, and a seventh pole,

Gilgamesh, take an eighth, a ninth, and a tenth pole,

Gilgamesh, take an eleventh, a twelfth pole!”

After one hundred twenty poles, Gilgamesh took off his garments,

Set up the mast in its socket, and used the garments as a sail.

Utnapishtim looked into the distance and, inwardly musing,

Said to himself: “Why are the sails of the vessel destroyed,

And why does one who is not of my service ride on the vessel?

This is no mortal who comes, but he is no god either.”

[Utnapishtim asks Gilgamesh the same questions already asked by Siduri and Urshanabi, and Gilgamesh replies with the same answers.]

And Gilgamesh said Utnapishtim:

“I have come here to find you, whom people call the ‘far-off,’

So I can turn to you for help; I have traveled through all the lands,

I have crossed over the steep mountains, and I have crossed all the seas to find you,

To find life everlasting.”

Utnapishtim answered Gilgamesh, saying:

“Does anyone build a house that will stand forever, or sign a contract for all time?

The dead are all alike, and Death makes no distinction between

Servant and master, when they have reached their full span allotted.

Then do the Anunnaki, great gods, settle the destiny of mankind;

Mammetum, Maker of Destiny with them, settles our destiny;

Death and Life they determine; but the day of Death is not revealed.”

Gilgamesh said Utnapishtim:

“I gaze on you in amazement, O Utnapishtim!

Your appearance has not changed, you are like me.

And your nature itself has not changed, in your nature you are like me also,

Though you now have eternal life. But my heart has still to struggle

Against all the obstacles that no longer bother you.

Tell me, how did you come to dwell here and obtain eternal life from the gods?”

[In the following passages, Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh the story of the flood. In the story of Atrahasis, another name for Utnapishtim, the reason for the flood is that humans have been too noisy and the gods cannot sleep. The gods use the flood as a way to deal with human overpopulation.]

Utnapishtim then said to Gilgamesh:

“I will reveal to you, O Gilgamesh, the mysterious story,

And one of the mysteries of the gods I will tell you.

The city of Shurippak, a city which, as you know,

Is situated on the bank of the river Euphrates. The gods within it

Decided to bring about a flood, even the great gods,

As many as there were. But Ea, the lord of unfathomable wisdom, argued with them.

Although he could not tell any human directly, he gave me a dream;

In the dream, he told their plan first to a reed-hut, saying:

‘Reed-hut, reed-hut, clay-structure, clay-structure!

Reed-hut, hear; clay-structure, pay attention!

Man of Shurippak, son of Ubara-Tutu,

Build a house, construct a ship;

Forsake your possessions, take heed!

Abandon your goods, save your life,

And bring the living seed of every kind of creature into the ship.

As for the ship, which you shall build,

Let its proportions be well measured:

Its breadth and its length shall bear proportion each to each,

And into the sea then launch it.’

I took heed, and said to Ea, my lord:

‘I will do, my lord, as you have commanded;

I will observe and will fulfill the command.

But what shall I say when the city questions me, the people, and the elders?’

Ea opened his mouth and spoke,

And he said to me, his servant:

‘Man, as an answer, say this to them:

“I know that Enlil hates me.

No longer can I live in your city;

Nor on Enlil’s territory can I live securely any longer;

I will go down to the sea, I will live with Ea, my lord.

He will pour down rich blessings.

He will grant fowls in plenty and fish in abundance,

Herds of cattle and an abundant harvest.”’

As soon as early dawn appeared,

I feared the brightness of the day;

All that was necessary I collected together.

On the fifth day I drew its design;

In its middle part its sides were ten gar high;

Ten gar also was the extent of its deck;

I added a front-roof to it and closed it in.

I built it in six stories,

Making seven floors in all;

The interior of each I divided again into nine partitions.

Beaks for water within I cut out.

I selected a pole and added all that was necessary.

Three shar of pitch I smeared on its outside;

Three shar of asphalt I used for the inside (to make it water-tight).

Three shar of oil the men carried, carrying it in vessels.

One shar of oil I kept out and used it for sacrifices,

While the other two shar the boatman stowed away.

For the temple of the gods I slaughtered oxen;

I killed lambs day by day.

Jugs of cider, of oil, and of sweet wine,

Large bowls, like river water flowing freely, I poured out as libations.

I made a feast to the gods like that of the New-Year’s Day.

I added tackling above and below, and after all was finished,

The ship sank into water two thirds of its height.

With all that I possessed I filled it;

With all the silver I had I filled it;

With all the gold I had I filled it;

With living creatures of every kind I filled it.

Then I embarked also all my family and my relatives,

Cattle of the field, beasts of the field, and the righteous people—all of them I embarked.

Ea had appointed a time, namely:

‘When the rulers of darkness send at eventide a destructive rain,

Then enter into the ship and shut its door.’

This very sign came to pass, and

The rulers of darkness sent a destructive rain at eventide.

I saw the approach of the storm,

And I was afraid to witness the storm;

I entered the ship and shut the door.

I entrusted the guidance of the ship to the boat-man,

Entrusted the great house, and the contents therein.

As soon as early dawn appeared,

There rose up from the horizon a black cloud,

Within which the weather god thundered,

And the king of the gods went before it.

The destroyers passed across mountain and dale.

They tore loose the restraints holding back the waters.

They caused the banks to overflow;

The Anunnaki lifted up their torches,

And with their brightness they illuminated the universe.

The storm brought on by the gods swept even up to the heavens,

And all light was turned into darkness. It flooded the land; it blew with violence;

And in one day it rose above the mountains.

Like an onslaught in battle it rushed in on the people.

Brother could not save brother.

The gods even were afraid of the storm;

They retreated and took refuge in the heaven of Anu.

There the gods crouched down like dogs, in heaven they sat cowering.

Then Ishtar cried out like a woman in travail,

And the lady of the gods lamented with a loud voice, saying:

‘The world of old has been turned back into clay,

Because I assented to this evil in the assembly of the gods.

Alas, that I assented to this evil in the council of the gods,

Alas, that I was for the destruction of my own people.

Where is all that I have created, where is it?

Like the spawn of fish it fills the sea.’

The gods wailed with her;

The gods were bowed down, and sat there weeping.

Their lips were pressed together in fear and in terror.

Six days and nights the wind blew, and storm and tempest overwhelmed the country.

When the seventh day arrived, the tempest, the storm, the battle

Which they had waged like a great host began to moderate.

The sea quieted down; hurricane and storm ceased.

I looked out upon the sea and raised loud my voice,

But all mankind had turned back into clay.

Like the surrounding field had become the bed of the rivers.

I opened the air-hole and light fell upon my cheek.

Dumfounded I sank backward and sat weeping,

While over my cheek flowed tears.

I looked in every direction, and behold, all was sea.

Now, after twelve days, there rose out of the water a strip of land.

To Mount Nisir the ship drifted.

On Mount Nisir the boat stuck fast and it did not slip away.

The first day, the second day, Mount Nisir held the ship fast, and did not let it slip away.

The third day, the fourth day, Mount Nisir held the ship fast, and did not let it slip away.

The fifth day, the sixth day, Mount Nisir held the ship fast, and did not let it slip away.

When the seventh day arrived

I sent out a dove, and let her go.

The dove flew hither and thither,

But as there was no resting-place for her, she returned.

Then I sent out a swallow, and let her go.

The swallow flew hither and thither,

But as there was no resting-place for her she also returned.

Then I sent out a raven, and let her go.

The raven flew away and saw that the waters were receding.

She settled down to feed, went away, and returned no more.

Then I let everything go out of the boat, and I offered a sacrifice.

I poured out a libation on the peak of the mountain.

I placed the censers seven and seven,

And poured into them calamus, cedar wood, and sweet incense.

The gods smelled the savor;

The gods gathered like flies around the sacrifice.

But when the lady of the gods, Ishtar, drew close,

She lifted up the precious necklace that Anu had made according to her wish and said:

‘All you gods here! by my necklace, I will not forget.

These days will I remember, never will I forget them.

Let the gods come to the offering;

But Enlil shall not come to the offering,

Since rashly he caused the flood-storm,

And handed over my people to destruction.’

Now, when Enlil drew close, and saw the ship, the god was angry,

And anger against the gods filled his heart, and he said:

‘Who then has escaped here with his life?

No man was to survive the universal destruction.’

Then Ninurta opened his mouth and spoke, saying to Enlil:

‘Who but Ea could have planned this!

For does not Ea know all arts?’

Then Ea opened his mouth and spoke, saying to Enlil:

‘O wise one among the gods, how rash of you to bring about a flood-storm!

On the sinner visit his sin, and on the wicked his wickedness;

But be merciful, forbear, let not all be destroyed! Be considerate!

Instead of sending a flood-storm,

Let lions come and diminish mankind;

Instead of sending a flood-storm,

Let tigers come and diminish mankind;

Instead of sending a flood-storm,

Let famine come and smite the land;

Instead of sending a flood-storm,

Let pestilence come and kill off the people.

I did not reveal the mystery of the great gods.

Utnapishtim saw this in a dream, and so he heard the mystery of the gods.’

Enlil then arrived at a decision.

Enlil went up into the ship,

Took me by the hand and led me out.

He led out also my wife and made her kneel beside me;

He turned us face to face, and standing between us, blessed us, saying:

‘Before this Utnapishtim was only human;

But now Utnapishtim and his wife shall be lofty like the gods;

Let Utnapishtim live far away from men.’

Then they took us and let us dwell far away.”

Utnapishtim said to Gilgamesh:

“Now as for you, which one of the gods shall give you the power,

So that you can obtain the life that you desire?

Now sleep!” And for six days and seven nights Gilgamesh slept.

Sleep came over him like a storm wind.

Then Utnapishtim said to his wife:

“Behold, here is the hero whose desire is life everlasting!

Sleep came over him like a storm wind.”

And the wife replied to Utnapishtim, the far-away:

“Restore him in health, before he returns on the road on which he came.

Let him pass out through the great door unto his own country.”

And Utnapishtim said to his wife:

“The suffering of the man pains you.

Well, then, cook the food for him and place it at his head.”

And while Gilgamesh slept on board the ship,

She cooked the food to place it at his head.

And while he slept on board the ship,

Firstly, his food was prepared;

Secondly, it was peeled; thirdly, it was moistened;

Fourthly, his food was cleaned;

Fifthly, [seasoning] was added;

Sixthly, it was cooked;

Seventhly, all of a sudden the man was restored, having eaten of the magic food.

Then spoke Gilgamesh to Utnapishtim, the far-away:

“I had collapsed into sleep, and you have charmed me in some way.”

And Utnapishtim said to Gilgamesh:

“I restored you when you ate the magic food.”

And Gilgamesh said to Utnapishtim, the far-away:

“What shall I do, Utnapishtim? Where shall I go?

The Demon of the Dead has seized my friend.

Upon my couch Death now sits.”

And Utnapishtim said to Urshanabi, the ferryman:

“Urshanabi, you allowed a man to cross with you, you let the boat carry both of you;

Whoever attempts to board the boat, you should have stopped him.

This man has his body covered with sores,

And the eruption of his skin has altered the beauty of his body.

Take him, Urshanabi, and bring him to the place of purification,

Where he can wash his sores in water that they may become white as snow;

Let him rub off his bad skin and the sea will carry it away;

His body shall then appear well and healthy;

Let the turban also be replaced on his head, and the garment that covers his nakedness.

Until he returns to his city, until he arrives at his home,

The garment shall not tear; it shall remain entirely new.”

And Urshanabi took him and brought him to the place of purification,

Where he washed his sores in water so that they became white as snow;

He rubbed off his bad skin and the sea carried it away;

His body appeared well and healthy again;

He replaced also the turban on his head;

And the garment that covered his nakedness;

And until he returned to his city, until he arrived at his home,

The garment did not tear, it remained entirely new.

After Gilgamesh and Urshanabi had returned from the place of purification,

The wife of Utnapishtim spoke to her husband, saying:

“Gilgamesh has labored long;

What now will you give him before he returns to his country?”

Then Utnapishtim spoke to Gilgamesh, saying:

“Gilgamesh, you have labored long.

What now shall I give you before you return to your country?

I will reveal to you, Gilgamesh, a mystery,

And a secret of the gods I will tell you.

There is a plant resembling buckthorn,

its thorn stings like that of a bramble.

If you eat that plant, you will regain the vigor of your youth.”

When Gilgamesh had heard this, he bound heavy stones to his feet,

Which dragged him down to the sea and in this way he found the plant.

Then he grasped the magic plant.

He removed the heavy stones from his feet and one dropped down into the sea,

And the second stone he threw down to the first.

And Gilgamesh said to Urshanabi, the ferryman:

“Urshanabi, this plant is a plant of great power;

I will take it to Uruk the strong-walled, I will cultivate the plant there and then harvest it.

Its name will be ‘Even an old man will be rejuvenated!’

I will eat this plant and return again to the vigor of my youth.”

[They start out to return home to Uruk.]

Every forty leagues they then took a meal:

And every sixty leagues they took a rest.

And Gilgamesh saw a well that was filled with cool and refreshing water;

He stepped up to it and poured out some water.

A serpent darted out; the plant slipped from Gilgamesh’s hands;

The serpent came out of the well, and took the plant away,

And he uttered a curse.

And after this Gilgamesh sat down and wept.

Tears flowed down his cheeks,

And he said to Urshanabi, the ferryman:

“Why, Urshanabi, did my hands tremble?

Why did the blood of my heart stand still?

Not on myself did I bestow any benefit.

The serpent now has all of the benefit of this plant.

After a journey of only forty leagues the plant has been snatched away,

As I opened the well and lowered the vessel.

I see the sign; this is an omen to me. I am to return, leaving the ship on the shore.”

Then they continued to take a meal every forty leagues,

And every sixty leagues they took a rest,

Until they arrived at Uruk the strong-walled.

Gilgamesh then spoke to Urshanabi, the ferryman, saying:

“Urshanabi, ascend and walk about on the wall of Uruk,

Inspect the corner-stone, and examine its brick-work, made of burned brick,

And its foundation strong. One shar is the size of the city,

And one shar is the size of the gardens,

And one shar is the size of Eanna, temple of Anu and Ishtar;

Three shar is the size of Uruk strong-walled.”

[Now that Gilgamesh knows that he cannot have eternal life, he focuses instead on learning about the afterlife. He tries to find a way to talk to Enkidu by bringing back his ghost to haunt him. Gilgamesh speaks to the Architect of the Temple, asking what he should do to avoid bringing back a ghost—while planning to do the opposite.]

The Architect answered Gilgamesh, saying:

“Gilgamesh, to avoid ghosts, if you go to the temple, do not wear clean garments;

Wear a garment that is dirty, so you do not attract them.

Do not anoint yourself with sweet oil, in case at its fragrance

Around you they gather: nor may you set a bow on the ground, or around you

May circle those shot by the bow; nor may you carry a stick in your hand,

Or ghosts who were beaten may gibber around you: nor may you put on a shoe,

Which would make a loud echo on the ground: you may not kiss the wife whom you love;

The wife whom you hate—you may not chastise her,

Yes, and you may not kiss the child whom you love,

Nor may you chastise the child whom you hate,

For you must mourn their [the ghosts’] loss of the world.”

So Gilgamesh went to the temples,

Put on clean garments, and with sweet oil anointed himself:

They gathered around the fragrance;

Around him they gathered: he set the bow on the ground, and around him

Circled the spirits—those who were shot by a bow gibbered at him;

He carried a stick in his hand, and the ghosts who had been beaten gibbered at him.

He put on a shoe and made a loud echo on the ground.

He kissed the wife whom he loved, chastised the wife whom he hated,

He kissed the child whom he loved, chastised the child whom he hated.

They mourned their loss of the world, but Enkidu was not there.

Gilgamesh went all alone to the temple of Enlil:

“Enlil, my Father, the net of Death has stricken me also, holding me down to the earth.

Enkidu—whom I pray that you will raise from the earth—was not seized by the Plague god,

Or lost through a battle of mortals: it was only the earth which has seized him.”

But Enlil, the Father, gave no answer.

To the Moon god Gilgamesh went:

“Moon god, my Father, the net of Death has stricken me also, holding me down to the earth.

Enkidu—whom I pray that you will raise from the earth—was not seized by the Plague god,

Or lost through a battle of mortals: it was only the earth which has seized him.”

But Sin, the Moon god, gave no answer.

Then to Ea Gilgamesh went:

“Ea, my Father, the net of Death has stricken me also, holding me down to the earth.

Enkidu—whom I pray that you will raise from the earth—was not seized by the Plague god,

Or lost through a battle of mortals: it was only the earth which has seized him.”

Ea, the Father, heard him, and to Nergal, the warrior-hero,

He spoke: “O Nergal, O warrior-hero, listen to me!

Open now a hole in the earth, so that the spirit of Enkidu, rising,

May come forth from the earth, and so speak with his brother.”

Nergal, the warrior-hero, listened to Ea’s words,

Opened, then, a hole in the earth, and the spirit of Enkidu issued

Forth from the earth like a wind. They embraced and grieved together. Gilgamesh said:

“Tell, O my friend, O tell me, I pray you,

What have you seen of the laws of the Underworld?”

Enkidu said: “Do not ask; I will not tell you—for, were I to tell you

Of what I have seen of the laws of the Underworld, you would sit down weeping!”

Gilgamesh said: “Then let me sit down weeping.”

Enkidu said: “So be it: the friend you cared for now has worms in his body;

The bride you loved is now filled with dust.

Bitter and sad is all that formerly gladdened your heart.”

Gilgamesh said: “Did you see a hero, slain in battle?”

“Yes—[when he died] his father and mother supported his head,

And his wife knelt weeping at his side.

The spirit of such a man is at rest. He lies on a couch and drinks pure water.

But the man whose corpse remains unburied on the field—

You and I have often seen such a man—

His spirit does not find rest in the Underworld.

The man whose spirit has no one who cares for it—

You and I have often seen such man—

Consumes the dregs of the bowl, the broken remnants of food

That are cast into the street.”

[One important lesson for all readers of the poem is, therefore, “Take good care of your dead.” The rest of the tablet is damaged, although one alternate version of the story ends with the funeral of Gilgamesh many years later. Interestingly, once he settles down to become a good ruler, there is nothing more to say.]