45 8.2: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity

Chapter 8: Race, Ethnicity, and Language

Introduction

Culture, Race, and Ethnicity

Culture, language, ethnicity, race, and national origin are related concepts by which individuals are assigned to social groups, but they are not one and the same. For example, persons of African descent living in the Caribbean, Latin America, Nigeria, South Africa, or the United States may be classified as falling within the same racial category, but they belong to different cultural groups. Jamaican or Haitian families living in California may be lumped into the same racial or ethnic category as Black or African American families that have lived in the United States for generations. Although language, ethnicity, and national origin may be associated with culture, none of them alone define a specific cultural group. For example, Spanish speakers in Europe, Mexico, Africa, Central or South America, and the United States share a language with common features, but may have divergent cultures and self-identify with different racial groups.

National origin—such as being from China, Sudan, or Peru—does not sufficiently specify a cultural group because within each of these nations exist groups with several distinct cultures. Racial group is sometimes confused with cultural group. Race is a social construct that has no basis in culture, biology, or genetics. Race is a social category that is based either on self-identification or how individuals are seen by others. This means that the traditional ethnic and racial categories such as those used in the U.S. Census are social categories that fail to specify culture even though they continue to be interpreted by many as cultural categories. [93]

In the U.S. Census, there are five categories of race:

- American Indian or Alaska Native. A person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America), and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment.

- Asian. A person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.

- Black or African American. A person having origins in any of the black racial groups of Africa. Terms such as “Haitian” can be used in addition to “Black or African American.”

- Hispanic or Latino. A person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race. The term, “Spanish origin,” can be used in addition to “Hispanic or Latino.”

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.

- White. A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.

Ethnicity comes closer to defining cultural groups than race or national origin, but it is not a perfect match. Ethnicity refers to a group’s identity and denotes a people bound by a common broad past. Members of an ethnic group often share a common ancestry, history, and sometimes language. To the extent that an ethnic group uses a common language, shares practices and beliefs, and has a common history, members of ethnic groups may be said to share a culture. However, ethnicity and culture are not always the same. Individuals may not necessarily identify strongly with the group to which they are assigned (in the minds of others). Nevertheless, ethnicity is a useful concept because it signals a group identity and a sense of connection and belonging. [94]

In the U.S. Census there are only two ethnicity categories : “Hispanic or Latino” and “Not Hispanic or Latino.” [95] But the idea that all Latinos are white or nonwhite is inaccurate. The idea that a large subgroup all has one big group identity is superficial and does not represent the reality today in California. [96]

Demographic Information for Young Children in California

In 2010, of the more than 2.5 million children under the age of five living in California, about half of these children were Latino (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). It is important to note that Latinos may be of any race, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. White non-Latino children make up 30 percent of children under five in California, Asian-Pacific Islanders make up 10 percent, Black or African Americans make up 6 percent, and the remaining 4 percent represent a wide range of ethnic groups (Whitebook, Kipnis, and Bellm 2008). [97]

Collectivist Versus Individualist Cultures

A feature that has often been used to distinguish societies and cultural groups is where they fall along a continuum from individualist to collectivist orientations.

In collectivist societies, the self is defined principally in terms of identity with the group (Roland 1988). When what may be good for the whole competes with what may be good for the individual, the good of the whole takes precedence. In societies at the collectivist end of the continuum, children are imbued with the sense that their behavior will reflect for the good or the bad on the rest of the group. They may be instilled with a sense of shame if they behave in a way that reflects badly on the group.

In a family with an individualist cultural orientation, each child has his or her own possessions. In some families with a more collectivistic perspective, private ownership is downplayed and everything is shared. When the family has that perspective, they may require sharing from infancy on; whereas someone with a child development background or a more individualistic orientation might hold the view that the child must understand the concept of ownership before he or she can become a truly sharing person and that understanding usually starts in the second year of life. Sharing of the program’s toys and materials is expected; however, if the child brings something from home, possessiveness is expected and there may be different rules about that in the program.

Individualist versus collectivist orientation should be understood as a tendency in a society rather than an absolute characteristic. Few would claim that pure forms of individualist and collectivist societies exist. Both orientations exist in most cultural groups, to varying degrees. This tendency is especially relevant in the context of teaching and learning, where children whose families emphasize a collectivist orientation may be more familiar with learning settings that focus more on group experiences and learning, while individualist orientations focus on individual work and learning, not in relation to the group. Individualist and collectivist orientations coexist within the same society. [99]

What Programs Can Do

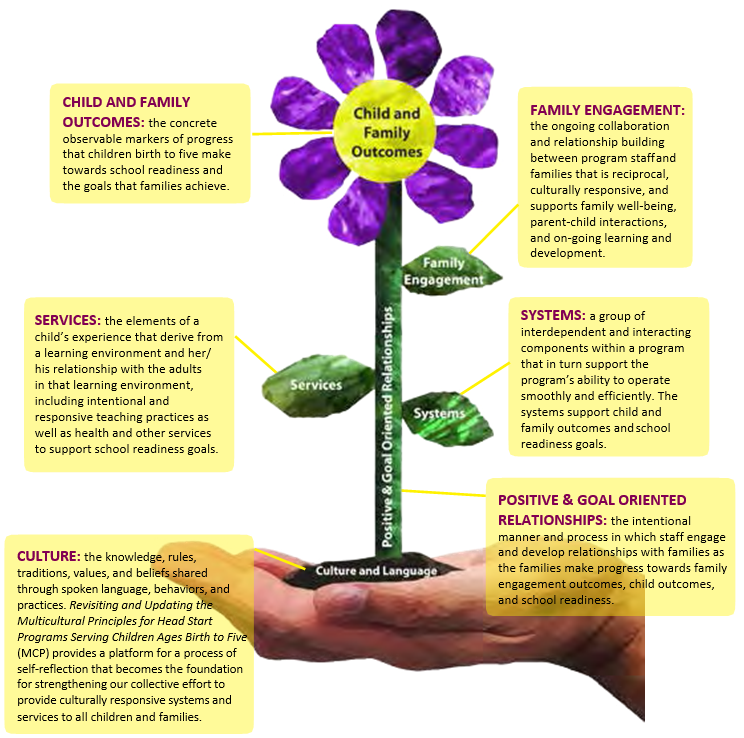

Because of the diversity and dynamism of cultures represented in California’s early childhood programs, efforts to profile cultural groups would be quickly outdated. In addition to the practices in Chapters 3 and 4, programs can also use Culturally Responsive Strength-Based (CRSB) Framework, which is used by Head Start, to address diversity. This framework presents the big picture and identifies the program pieces that support the growth and development of all children.

Figure 8.2: The elements of the CRSB Framework. [100]

Coupled with a culturally responsive approach, the CRSB Framework is a strength-based approach. The focus is on what children know and can do as opposed to what they cannot do or what they do not know. Cultural, family, and individual strengths are emphasized, not just the negative and proposed interventions to “fix the problem” that resides with the children, their families, and/or their communities.

|

|

The strengths approach has a contagious quality and it intuitively makes sense to those who reflect a “cup half full” attitude in life. — Hamilton & Zimmerman, 2012 If we ask people to look for deficits, they will usually find them, and their view of the situation will be colored by this. If we ask people to look for successes, they will usually find it, and their view of the situation will be colored by this. — Kral, 1989 (as cited in Hamilton & Zimmerman, 2012) [101] |

The CRSB Framework should be used with the understanding that children are influenced by many environments, as represented in a bioecological systems model. A bioecological systems model captures the variety of environments that impact individual development over the course of a lifetime. Young children do not live in a vacuum, but co-exist in many environments that affect their development, starting with the family, extending into the community, and reaching out into the economic and political spheres.