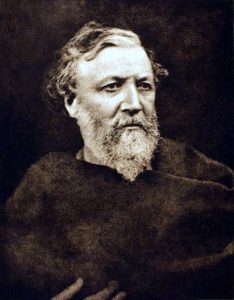

68 Biography: Robert Browning

Portrait of Anna Laetitia Barbauld

Artist | Julia Margaret Cameron Source | Wikimedia Commons License | Public Domain

(1812-1889)

Robert Browning’s father, Robert Browning, worked as a clerk in the Bank of England. His mother, Sarah Anna Wiedemann, was devoutly religious. So Browning was born into an apparently conventional middle-class Victorian household. But Browning’s father had a strong scholarly bent and encouraged his son to delve into art and literature, particularly by means of the quirky personal library Browning senior had amassed. Browning consequently became something of an autodidact, even as he received formal education at home from his father. His mother, too, had a deep love of music that seems to have influenced Browning’s work, both in style and subject matter.

Critics deemed Browning’s first published work, Pauline: A Fragment of a Confession (1833), as too inclined towards Romanticism, revealing too much influence by Shelley. He consequently moved towards more objective expression, in both dramatic and poetic form, particularly his Dramatic Lyrics (1842). Many poems in this collection take the Dramatic Monologue form. This form takes a relativistic attitude to Truth. Because it derives its effects from the ambiguity of values, it makes demands on the reader’s perceptivity. Dramatic Monologues always have a single, first person speaker, an audience, and an action. The action is usually a deepening of the reader’s understanding of the speaker’s mind.

The Dramatic Monologue became a popular form in the Victorian era probably due to a reaction to Romanticism. The Romantics established the “I” as the prophetic speaker, the visionary voice, the authority. The Victorians were suspicious of this prophetic position; they wanted to establish a difference between the speaker and the poet and their different points of view, so they resorted to drama. Like the Romantics, though, Browning’s poetry worked toward a greater understanding of human nature. The speakers of many of his poems stretch stereotypes and expectations. The titular speaker of “Porphyria’s Lover,” with terrifying passive aggression, strangles Porphyria to save her from her frivolous love—even though his voice, stance, and actions express extraordinary anger at a woman who rejects him as a social inferior yet who has “loved” him and clearly enjoys his suffering love for her.

The Duke of Ferrari, the speaker in “My Last Duchess,” seems indifferent to anyone’s judgement but his own—to the point that he confesses to having his wife killed for not sufficiently deferring to his pride. The subject matter of this poem suggests Browning’s interest in women’s issues, in the situation of women condemned to remain under the rule of fathers and husbands who may be domestic tyrants and even murderers. And Browning’s interest in religion appears through the “The Bishop Orders His Tomb,” which criticizes the Oxford Movement and its goal of having England return to “ideal” Roman Catholicism.

In 1846, Browning eloped with Elizabeth Barrett to Italy where they had a son, Robert “Pen” Browning (1849-1912). After Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in 1861, Robert and Pen returned to London. Browning began to win critical acclaim, particularly with the publication of his monumental The Ring and the Book (1868-69), a poem based on the seventeenth-century trial testimony of an Italian nobleman condemned to death for murdering his wife.

This material is from British Literature II: Romantic Era to the Twentieth Century and Beyond by Bonnie J. Robinson from the University System of Georgia, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms.