33 Biography: Jonathan Swift

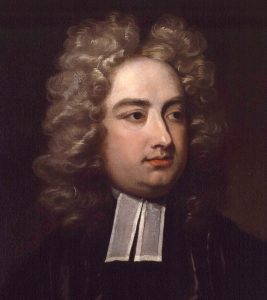

Portrait of Jonathan Swift

Artist | Charles Jervas Source | Wikimedia Commons License | Public Domain

(1667-1745)

Born in Dublin posthumously to an Anglican father Jonathan Swift and Anglican mother, Jonathan Swift depended on the generosity of his uncle for both his upbringing and education. He studied at Kilkenny School and then at Trinity College, Dublin, from which he graduated in 1689.

After a frustratingly unproductive stint in England as personal secretary to Sir William Temple (1628-1699), a family friend and diplomat with connections to the Royal Court, Swift returned to Ireland where he was ordained as an Anglican priest. After an appointment to a church in Northern Ireland, followed by again unproductive work in England with Temple and then with Charles Berkeley, Earl of Berkeley (1649-1710), Swift took an ecclesiastical living near Dublin. He also began a long, probably platonic relationship with a woman named Esther Johnson (1681-1728) with whom he lived in close emotional contact for the rest of her life. The letters he wrote her, collected in Journal to Stella (1766), give an intimate view of Swift’s political and religious activities and friendships.

At Temple’s encouragement, Swift wrote laudatory poetry. On his own initiative, he wrote satire, beginning with A Tale of a Tub (1704) which he published anonymously, a satire on excesses in religion, politics, human pride, literature, science—and much else. Swift’s hopes for his church career were tied to politics, and he eventually allied himself with the Tory party and its resistance to Dissenters and nonconformists. On their behalf, Swift wrote propagandist satire in The Examiner. He became particularly close to the activities and political ambitions of Robert Harley and Henry St. John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, the most prominent Tory rulers. Their debacle and loss of power cost Swift a hoped-for Bishopric in the English Church. Queen Anne, personally offended by A Tale of a Tub which she thought obscene, effectively exiled Swift to Ireland by appointing him as the Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin.

His political and moral acumen persisted strong, leading him to write the Drapier’s Letters to the People of Ireland (1724-35), pamphlets against British corruption and exploitation of the Irish economy. These pamphlets made Swift a

hero to the Irish. Although published anonymously, the Irish populace knew their writer’s identity; despite charges of sedition against the writer and offers of reward for identifying the writer, the Irish never informed against Swift. He further vilified British exploitation of Irish resources in A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People of Ireland from Being a Burden to Their Parents (1729). It offers a literal rendition of this exploitation by suggesting the Irish sell their children as food to the wealthy.

His Gulliver’s Travels (1726) vilified humankind for its misdirected pride and various atrocities against humanity. The force, range, and bitterness of this text’s indictment against humans who wrongly assume their own rationality strike home even today. Generations of critics resisted its satire, considering it the work of a madman. Indeed, Swift did decline into senility and dependency (Samuel Johnson later claimed that Swift in this condition was displayed as an object of entertainment). Gulliver’s Travels’ prose style shifts markedly among its four books, suggesting a possible mental incoherence. The beauties and wonders of Lilliput are pushed aside in Brobdingnag, with its stinking giants, and Houyhnhnm land, with the vicious and howling Yahoos. But Swift had a very serious point to make about human nature, one that he seemed to want to drive home (and against which his readers, and parishioners, may have been dully resistant). So he was artful and deft but also heavy-handed and blunt. By having the Houyhnhnms (“superior” horses) reject Gulliver for being a complete Yahoo (humans), Swift shows that humans are not rational animals but only capable of rationality. The distinction, and its consequences, was too important for Swift not to want to drive it home however he could. After his death, Swift was buried near Esther Johnson in St. Patrick’s.

This material is from British Literature: Middle Ages to the Eighteenth Century and Neoclassicism by Bonnie J. Robinson from the University System of Georgia, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms