36 Why Does Experiencing ‘Flow’ Feel So Good? A Communication Scientist Explains

Learning Outcomes

- Apply the reading process to “Why Does Experiencing ‘Flow’ Feel So Good? A Communication Scientist Explains.”

- Summarize the article.

- Respond to the article.

- Connect the ideas in the article to your personal experience.

Preview the Article

Follow the steps below to preview the article “Why Does Experiencing ‘Flow’ Feel So Good? A Communication Scientist Explains.” Ideally, you should print the article and write your responses in the margins of the printed copy. To read more about previewing, visit the chapter on previewing a reading.

- Read the title. What does it make you think about? What do you think the article is about? What questions do you have? Record your predictions and questions on the printed copy of the article next to the title.

- Have you heard of the term “flow” in relation to psychology? If not, Google it. Record what you learn on the printed copy of the article.

- Read the first two or three paragraphs. What additional predictions do you now have about the article? What additional questions do you have? Record them on the printed copy of the article.

- Scan the article and notice the headings (e.g. What is it like to be in flow?). What additional thoughts or questions do these raise? Record them on the printed copy of the article.

- Scan the bolded and underlined vocabulary in the article. If there are any words that you do not know well, look them up in a print or online dictionary and write some notes about their meanings on the printed copy of the article. Keep in mind that some words have multiple meanings. You may need to read the sentence containing the word to understand the word’s usage. Additionally, this article contains several words often used when discussing research studies, such as hypothesis (paragraph 15), correlational (paragraph 17), and causal (paragraph 17). Make a note of these words, which you are likely to encounter in other texts that discuss the results of research.

- Based on your preview of the article, what do you think is the central point of the article? (Don’t worry if you are not sure. This is a prediction or guess – you do not have to be correct as long as you are engaging your brain.) Record your prediction on the printed copy of the article.

- Based on your preview, do you predict that the article is narrative, expository, or argumentative?

Read Interactively

Now, read the article using the guidelines from the chapter on reading interactively. As you read, follow these steps to engage with the text.

- Pause to confirm or revise your predictions and to answer the questions you posed while previewing the article. Write down those revised predictions and responses to the questions as you read. If you cannot find the answers to your questions, save them for further research and discussion.

- Pause at other points to check for understanding of what you just read. Can you explain key ideas in your own words yet? If not, reread to clarify. Ideas that come later in a text build on the previous ones. Therefore, it makes no sense to keep reading if you did not understand something or if you became distracted. Anyone can become distracted while reading, so don’t hesitate to use the strategy of rereading when necessary.

- Pay attention to any vocabulary words that are confusing. Look up the words in a dictionary if they are interfering with your understanding, or mark them to return to later.

- Record any opinions or reactions you have to the reading in the margins of the article.

- Write down any further questions that develop as you read.

Why does experiencing ‘flow’ feel so good? A communication scientist explains

Richard Huskey, University of California, Davis

1 New years often come with new resolutions. Get back in shape. Read more. Make more time for friends and family. My list of resolutions might not look quite the same as yours, but each of our resolutions represents a plan for something new, or at least a little bit different. As you craft your 2022 resolutions, I hope that you will add one that is also on my list: feel more flow.

2 Psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi’s research on flow started in the 1970s. He has called it the “secret to happiness.” Flow is a state of “optimal experience” that each of us can incorporate into our everyday lives. One characterized by immense joy that makes a life worth living.

3 In the years since, researchers have gained a vast store of knowledge about what it is like to be in flow and how experiencing it is important for our overall mental health and well-being. In short, we are completely absorbed in a highly rewarding activity – and not in our inner monologues – when we feel flow.

4 I am an assistant professor of communication and cognitive science, and I have been studying flow for the last 10 years. My research lab investigates what is happening in our brains when people experience flow. Our goal is to better understand how the experience happens and to make it easier for people to feel flow and its benefits.

What it is like to be in flow?

5 People often say flow is like “being in the zone.” Psychologists Jeanne Nakamura and Csíkszentmihályi describe it as something more. When people feel flow, they are in a state of intense concentration. Their thoughts are focused on an experience rather than on themselves. They lose a sense of time and feel as if there is a merging of their actions and their awareness. That they have control over the situation. That the experience is not physically or mentally taxing.

6 Most importantly, flow is what researchers call an autotelic experience. Autotelic derives from two Greek words: autos (self) and telos (end or goal). Autotelic experiences are things that are worth doing in and of themselves. Researchers sometimes call these intrinsically rewarding experiences. Flow experiences are intrinsically rewarding.

What causes flow?

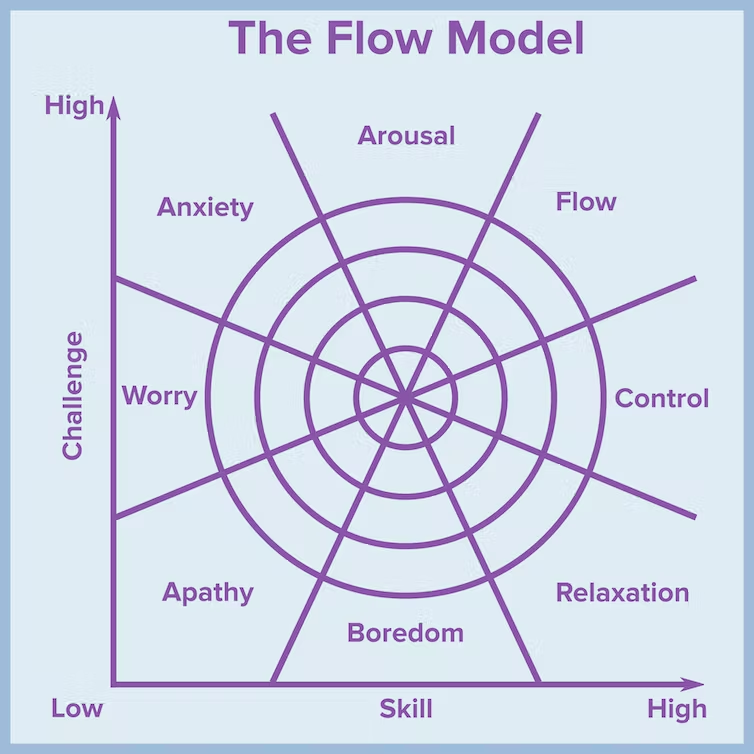

7 Flow occurs when a task’s challenge is balanced with one’s skill. In fact, both the task challenge and skill level have to be high. I often tell my students that they will not feel flow when they are doing the dishes. Most people are highly skilled dishwashers, and washing dishes is not a very challenging task.

8 So when do people experience flow? Csíkszentmihályi’s research in the 1970s focused on people doing tasks they enjoyed. He studied swimmers, music composers, chess players, dancers, mountain climbers and other athletes. He went on to study how people can find flow in more everyday experiences. I am an avid snowboarder, and I regularly feel flow on the mountain. Other people feel it by practicing yoga – not me, unfortunately! – by riding their bike, cooking or going for a run. So long as that task’s challenge is high, and so are your skills, you should be able to achieve flow.

9 Researchers also know that people can experience flow by using interactive media, like playing a video game. In fact, Csíkszentmihályi said that “games are obvious flow activities, and play is the flow experience par excellence.” Video game developers are very familiar with the idea, and they think hard about how to design games so that players feel flow.

Why is it good to feel flow?

10 Earlier I said that Csíkszentmihályi called flow “the secret to happiness.” Why is that? For one thing, the experience can help people pursue their long-term goals. This is because research shows that taking a break to do something fun can help enhance one’s self-control, goal pursuit and well-being.

11 So next time you are feeling like a guilty couch potato for playing a video game, remind yourself that you are actually doing something that can help set you up for long-term success and well-being. Importantly, quality – and not necessarily quantity – matters. Research shows that spending a lot of time playing video games only has a very small influence on your overall well-being. Focus on finding games that help you feel flow, rather than on spending more time playing games.

12 A recent study also shows that flow helps people stay resilient in the face of adversity. Part of this is because flow can help refocus thoughts away from something stressful to something enjoyable. In fact, studies have shown that experiencing flow can help guard against depression and burnout.

13 Research also shows that people who experienced stronger feelings of flow had better well-being during the COVID-19 quarantine compared to people who had weaker experiences. This might be because feeling flow helped distract them from worrying.

What is your brain doing during flow?

14 Researchers have been studying flow for nearly 50 years, but only recently have they begun to decipher what is going on in the brain during flow. One of my colleagues, media neuroscientist René Weber, has proposed that flow is associated with a specific brain-network configuration.

15 Supporting Weber’s hypothesis, studies show that the experience is associated with activity in brain structures implicated in feeling reward and pursuing our goals. This may be one reason why flow feels so enjoyable and why people are so focused on tasks that make them feel flow. Research also shows that flow is associated with decreased activity in brain structures implicated in self-focus. This may help explain why feeling flow can help distract people from worry.

16 Weber, Jacob Fisher and I have developed a video game called Asteroid Impact to help us better study flow. In my own research, I have participants play Asteroid Impact while having their brain scanned. My work has shown that flow is associated with a specific brain network configuration that has low energy requirements. This may help explain why we do not experience flow as being physically or mentally demanding. I have also shown that, instead of maintaining one stable network configuration, the brain actually changes its network configuration during flow. This is important because rapid brain network reconfiguration helps people adapt to difficult tasks.

What more can the brain tell us?

17 Right now, researchers do not know how brain responses associated with flow contribute to well-being. With very few exceptions, there is almost no research on how brain responses actually cause flow. Every neuroscience study I described earlier was correlational, not causal. Said differently, we can conclude that these brain responses are associated with flow. We cannot conclude that these brain responses cause flow.

18 Researchers think the connection between flow and well-being has something to do with three things: suppressing brain activation in structures associated with thinking about ourselves, dampening activation in structures associated with negative thoughts, and increasing activation in reward-processing regions.

19 I’d argue that testing this hypothesis is vital. Medical professionals have started to use video games in clinical applications to help treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. Maybe one day a clinician will be able to help prescribe a Food and Drug Adminstration-approved video game to help bolster someone’s resilience or help them fight off depression.

20 That is probably several years into the future, if it is even possible at all. Right now, I hope that you will resolve to find more flow in your everyday life. You may find that this helps you achieve your other resolutions, too.![]()

Richard Huskey, Assistant Professor of Communication and Cognitive Science, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Reflect

After reading the article, use the following questions to reflect on the content of the article and your reading process. See the chapter about reflecting for a discussion of why this is a crucial step.

- Try to paraphrase the main idea in a sentence. This may be challenging because you have read the article only once. If you are struggling, do your best. You can refine this when you reread and summarize the article.

- Is the article primarily narrative, expository, or argumentative? What is the purpose of the article? In other words, why do you think the author wrote it?

- Which predictions were accurate, and which did you have to revise?

- As you previewed the article, you wrote questions. What questions remain unanswered after reading the article?

- What else do you want to know about the article or topic of the reading? Write down any additional questions.

- How did previewing the article help you to understand and engage with the text while reading?

- Where did you struggle to understand something in the text, and how did you work through it?

- What, if anything, could you have done differently to improve your reading process?

Summarize

Complete a summary of the article by following these steps. Make sure you have read the chapters about Reading to Summarize before proceeding with the summary.

- Reread the article and complete the Summary Notes. See Preparing to Summarize for a review of this topic and an example.

- Then, use your Summary Notes to write a one-paragraph summary of the article. See Writing a Summary for a review of this topic and an example. Make sure that you include in-text citations and the Work Cited.

- Use the self-assessment/peer review questions from Evaluating a Summary to self-assess your summary or invite a peer to provide feedback.

- Use the self-assessment or peer feedback to make changes to your summary.

Make sure you are comfortable with your summary before advancing to the response. If you misunderstand something in the article, then your response may be skewed based on that misunderstanding.

Respond

Write a response to the article by following these steps. Make sure you have read the chapters about Reading to Respond before proceeding with the summary.

- Use the Response Questions from Preparing to Respond to brainstorm possible ideas for your response. See the example in that same chapter.

- Read over your replies to the Response Questions. Choose one idea to write about in your response. Express that idea in a topic sentence. See Writing a Topic Sentence for a Response for examples. Ask a peer for feedback on your topic sentence.

- Brainstorm about possible support you could use in your response. See Generating Support for a Response for examples.

- Use your topic sentence and ideas from the list of support to write a one-paragraph response. See Writing a Response writing guidelines and examples. Make sure that you include the Work Cited and in-text citations for any quotes or specific ideas from the article.

- Use the self-assessment/peer review questions from Evaluating a Response to evaluate your response or have a peer provide feedback.

- Use the self-assessment or peer feedback to make improvements to your response.

Extend: Connect and Reflect

Identify an activity that would help you to enter a state of flow. As Richard Huskey states, in order to achieve flow, the activity you choose should be something fairly challenging, and you should have a reasonably high skill level with that task so that it requires concentration but is also somewhat automatic for you (par. 7). For example, if you play soccer, you might choose to practice dribbling the ball up and down a soccer field or in a grassy area. If you are a musician, you might play your instrument for a while.

Engage in the activity for at least 15 minutes. Reflect on your experience. Was it hard to achieve flow? What was your mind doing during the activity? How did you feel after the activity? Write down your reflections on your experience. Share your experience with your peers.