Theoretical Perspectives on Adolescence

Understand the concept of a research perspective.

Highlight developments in the Psychoanalytic tradition to adolescent psychology.

Understand the role that the Learning tradition played in the development of psychology.

Become aware of Piaget’s contributions to adolescent development theory.

Delineate between Biological perspectives and other paradigms.

Define central features of Humanistic Psychology relevant to adolescent development.

Apply the Ecological and Systemic approaches to adolescent life functioning.

WHAT ARE PSYCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES?

There are many statements that people make about adolescence. Some are based on opinions or personal experiences. While this is not necessarily wrong, analyzing adolescence from personal experience presents problems. Everyone’s experience is different. There is no way to determine what is true.If your teenage years were positive, then you are more apt to view the period positively. Similarly, suppose your experiences were primarily negative. In that case, you might be more likely to see adolescence as a sad and challenging time. Thus, personal experience may be a good starting point for gaining ideas to begin an inquiry. Still, it is rarely helpful to use our own experiences alone to draw conclusions that apply to diverse people.

The process of scientific research allows our findings to be more objective. In school, we take classes in science, yet the term can be confusing and intimidating. But in reality, science is just a specific way of conducting an inquiry and looking at the evidence. Scientists are always looking for alternative and logical explanations. Science supports explanations with the most evidence. Then scientists revise their theories if necessary and get better pictures of what is likely to be true, based on the existing evidence.

Some people criticize scientists for frequently changing their minds. However, scientists change their beliefs when they think they have been wrong. They constantly look at the evidence, including new evidence. They try to revise their ideas if new evidence supports new conclusions. They should always be skeptical, even of their own previous research. Therefore, to think like a good scientist is to have both curiosity and lots of skepticism. This is why scientists may seem to change their minds so frequently, especially to people who do not have training in science.

Psychology, the science of behavior and thinking, tries to categorize different ways of looking at psychological data into research perspectives. Perspectives, also called paradigms or theoretical orientations, among other terms, are ways that researchers approach topics. They indicate similar assumptions about research. Researchers that share perspectives often share presumptions about the world and about their subject matter. They may use the same set of theories and research techniques. Research techniques are discussed further in Unit 3.

There are several different theoretical perspectives in adolescent research. These perspectives or paradigms are also found in other areas of psychology. You may have heard about them in other classes. The discussion here highlights some, though not all, of the major perspectives and how they apply to adolescent psychology research.

None of these perspectives is entirely right or wrong. None has all of the answers. Perspectives are helpful if they aid us in producing hypotheses and ways of testing them. Perspectives are ways of asking questions and finding useful solutions. Some perspectives are more valuable in answering some types of questions than others. Sometimes problems can benefit from being studied from multiple perspectives or paradigms.

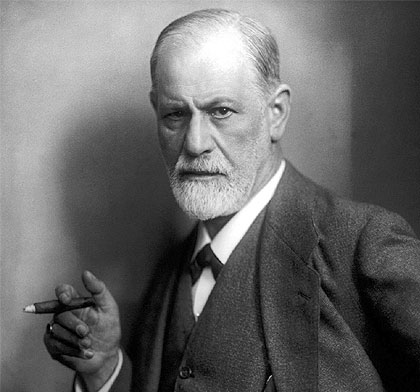

One of the most important paradigms in the history of psychology is Psychoanalytic Theory, pioneered by Sigmund Freud, the well-known Austrian psychiatrist. The theories were also advanced by his adherents, including his daughter Anna Freud. She made substantial contributions on her own that were different from her father’s. Freud’s theories were called a psychanalytic perspective. Revisions to them were often labeled psychodynamic theories (Wolitzky, 2016).

Freud’s theories are probably best understood against the backdrop of early 20th Century society. They seemed highly controversial but also very remarkable. Freud believed that we often do not really know why we act the way we do. This was shocking at the time. His central contribution is that much of human behavior is caused by unconscious motivations. He believed that these were primarily associated with sexuality and aggression. This pronouncement was even more shocking during the first half of the 20th Century when he first wrote it than it would be today.

Sigmund Freud Image is in the public domain.

Freud believed that the unconscious mind guided most of our behaviors. However, this aspect of the mind could not be observed directly. Regardless, it constantly left clues about its existence. The purpose of psychiatry was to look for these clues in patients, interpret them, and eventually provide patients insight about themselves through these interpretations. In many cases, Freud believed, this insight would eventually help cure patients(Knight, 2016).

Freud formed theories that emphasized that early experiences were crucial in personality development and in subsequent abnormal behavior. Unfortunately, his findings were often based on observations from his clinical work with just a few people. These days scientists realize that this is not a way to reach valid conclusions. While case studies are useful, they are never sufficient proof.

Table 2.1 illustrates Freud’s well-known psychosexual stages. These are so common that you may have heard of them many times previously.

Table 2.1 Freud’s Stages of Development

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Freud believed that we all pass through these psychosexual stages but that we likely have little recall of them. They occur relatively unconsciously. Only when they are disrupted or when we encounter problems later in life are we likely to recall clues of their existence. He believed it is sometimes necessary to identify them through a particular therapy type that he pioneered psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis is a lengthy treatment process, generally taking several sessions a week for several years. At the end of successful psychoanalysis, the patient gains insight. With the help of their therapist, they can often be cured of their unconscious conflicts, which Freud believed were the cause of most mental disorders.

Is Freud correct? Do we all pass through these stages and have little or no conscious recollection of them? Are these types of conflicts the cause of most mental disorders? As you can imagine, many people disagreed with him. Many others modified his theories to make them more useful. Anna Freud, his daughter, presented a more helpful set of ideas based on some aspects of his views (Wolitzky, 2016). She introduced the concept of “ego defense” and many concepts that therapists of adolescents often use to this day. Her theories parted substantially from her father’s, yet she remained committed to his idea of development. Many psychotherapists found her contributions of enduring value.

Most researchers do not accept Freud’s theories as necessarily or completely true but believe they contained some valuable ideas. Many psychologists, especially clinicians, think they have enough good ideas to be used in therapy with at least a subset of clients. Some students of behavior do not accept Freud’s theories but acknowledge that they are “somewhat true.” Others passionately disagree with his views and believe they are incorrect or outdated. Nevertheless, a few psychologists and other mental health professionals are still strong adherents of Freud and his theories, even to this day.

Many of Freud’s theories are criticized because they seem absurd. They are also very sexist. In addition, they seem highly culturally biased, favoring Europeans, mainly European males. His views were also hostile towards people of faith and also towards gays and lesbians.

Furthermore, Freud did not appear to believe it was necessary to do scientific research as research is conducted today. He often thought that the process of clinical observation and insight alone was sufficient for realizing what is true. We know that this is not good science. Clinical observation is frequently insightful but can often be misleading and can produce biasing results.

Science needs to test its hypotheses. Many people believe that Freud’s theories are so general that they are impossible to test. They are too vague. Freud himself may have also thought this. However, some researchers believe that Freud has not been supported in areas where his theories can be tested. Others disagree and say they have received at least some support. One hundred years after his time, people are still debating whether the evidence supports him.

However, Freud and Freud’s theories are still taught in the 21st Century because some of his insights were very helpful. Freud was a starting point. His ideas have generated many other valuable approaches. Perhaps more importantly, Freud’s theories are constantly being revised and combined into newer methods by theorists of many types.

Anna Freud, Founder of Ego Psychology Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC

Perhaps the most practical current application of Freud is in the areas of psychological trauma. Freud believed that events occurring early in life could have lifelong influences. It is now recognized that exposure to trauma early in life can have profound and lifelong consequences. Similarly, traumas during the teen years may have psychologically crippling effects that may last years or longer. Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, which Freud pioneered, can help treat trauma and many other disorders.

Alfred Adler is sometimes classified as a psychoanalytic theorist in Freud’s shadows. However, many people believe he was much more. Adler, an Austrian physician, was one of Freud’s earliest and most enthusiastic followers. This, however, did not last long. He was also the first close associate to disagree with and eventually to break with Freud and his inner circle (Ryckman, 2004). Adler criticized Freud, and their once-close friendship never recovered. Adler believed Freud’s theories were too narrow. He thought that people have many motives in their lives other than sex and aggression. Adler emphasized social motives. He believed that people responded to others and not necessarily in response to unconscious drives.

Unlike Freud, Adler was a strong proponent of teleology, meaning that he believed people act for a purpose. People work towards goals. Freud saw behavior as being caused chiefly by unconscious motives that a person could not recognize. Adler disagreed. Although unconscious behavior is essential to understand, people can also set their own purposes. They can consciously strive towards these self-selected goals. They can overcome their unconscious conflicts. They do not have to be driven by forces that they do not control.

Adolescents, Adler believed, often act confused because their goals are confused. When their aspirations become more consistent, their behavior will usually conform to the standards set by society. Adler was against excessively harsh punishment to teenagers and other juveniles, which was very popular in his day. He believed that some younger people simply lack the maturity to make reliably correct decisions. Given adequate time, he argued, most people will mature correctly. They will be able to act responsibly. While this seems common sense these days in Adler’s time, this statement was highly controversial.

Adler, unlike Freud, was a proponent of free will. He believed that everyone had a choice to do better. Freud disagreed, thinking that our behavior was determined by our conflicts and past traumas. Adler emphasized that biology, which we now understand related to genetics, influences people’s behaviors. But people can and do overcome the physical limits imposed by biology. Everyone, according to Adler, has their own constitutional inferiority or inborn tendencies to some types of weaknesses. However, we are also free to challenge our limitations and rise to new and different potentials, finding unexpected areas of talent. This is part of our human nature.

To Adler, the period of adolescence is when people begin to show that they can transcend the weaknesses they are faced with and develop new talents (Carlson, Watts, & Maniacci, 2006). Thus, the adolescent years offer a profound chance for people to experience personal growth and an opportunity to strive towards excellence.

Adler also emphasized that people’s thoughts and beliefs are essential in determining their personalities and behaviors. To Freud, personality is a fixed pattern usually set in early childhood. To Adler, personality can change if a person’s thoughts, behaviors, or social environment changes. Thus, any of these areas will generate a change. This conceptualization is recognized as one of the frameworks for cognitive behavioral therapy discussed in a later unit.

Erik Erikson was a European theorist who later emigrated to America. He was influenced by the Freudians, especially by Anna Freud, whom he worked with closely. Erikson was remarkable because he was largely self-taught. He had very little formal education. Despite this, he wrote extensively and shaped developmental psychology and specifically the study of adolescent development (Wolitzky, 2016).

Erikson believed that our personality continues to change throughout our lifespan as we face ongoing challenges in living. He identified eight stages he thought that everyone passed through in life. He also identified the conflicts that were associated with each of these stages.

|

Table 2.2 – Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory Name of Stage and Age |

|

|

Trust vs. mistrust (0-1) |

The infant must have basic needs met to feel that the world is trustworthy. |

|

Autonomy vs. shame and doubt (1-2) |

Toddlers have newfound freedom. They feel good about trying out their skills in the world. |

|

Initiative vs. Guilt (3-5) |

Preschoolers tackle many independent activities. They enjoy doing things “all by myself.” |

|

Industry vs. inferiority (6-11) |

School-aged children focus on accomplishments. They begin making comparisons between themselves and others. |

|

Identity vs. role confusion (adolescence) |

Adolescents try to gain a sense of identity as they experiment with various roles, beliefs, and ideas. |

|

Intimacy vs. Isolation (young adulthood) |

In our 20s and 30s, we make some of our first long-term commitments in intimate relationships. |

|

Generativity vs. stagnation (middle adulthood) |

The 40s through the 60s focus on being productive at work and home. People are motivated by wanting to feel that we have contributed to the world. |

|

Integrity vs. Despair (late adulthood) |

People look back on life and hope to see something positive. They believe that they have lived well if we have a sense of integrity and lived according to their beliefs. |

_____________________________________________________

Erikson’s contributions were in many areas and not just to developmental or adolescent psychology. These include personality theory and abnormal psychology, where his contributions remain essential. However, his work was considered perhaps the most important for understanding adolescence. Like Adler, he believed that the adolescent’s primary task was to establish a sense of “Who am I? What can I do?”. This was made easier if society allowed people to have some degree of freedom regarding various roles.

This task was also easier where society had a more specific set of rites of passage. This included well-defined rituals. When the path to adulthood was often poorly defined, Erikson believed young people were at high risk for developing psychological problems. In addition, historical periods when adolescents did not have the freedom to find out about their true natures were also risky for adolescent development.

The cognitive perspective in developmental psychology emphasizes how we think and the role of thinking in development. One of the most notable theorists in this domain was the Swiss psychologist and botanist Jean Piaget. Piaget’s theories and research were truly unique. His work was exacting, complex, and comprehensive (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009b).

Piaget’s theories and observations suggested that children and adolescents view the world very differently than adults. They think differently because their thought processes and perceptions are different. Their cognitive structures, which are how they think about the world and respond to it, are predictably different.

Piaget discovered that there are sequential stages of cognitive development. Children are in earlier cognitive stages than adolescents. Consequently, their thinking is different than adolescents’. Even the most intelligent child will see the world as a child does and think in a childlike fashion. While this seems obvious to us now, before Piaget, it was not apparent at all. Children were often viewed as miniature adults or “adult-like” individuals who simply lacked sufficient learning and life experiences. Piaget showed that children think differently from adolescents. Adolescents also may think differently from adults.

He showed this through many innovative experiments. For example, Piaget invented many elaborate tests to determine how children and adolescents think about the world and respond to it.

Press this link to Piaget’s stages

https://iastate.pressbooks.pub/parentingfamilydiversity/chapter/piaget/

There is substantial empirical support for Piaget’s theories. Piaget’s research regarding children shows that there are clearly cognitive differences in the thinking styles associated with development. However, subsequent researchers have found that Piaget’s stages do not always hold true for everyone. Children do not always precisely pass through the stages that he described. They may not be as universal as he believed. Cultural factors may also help determine these sequences.

Regardless, despite over 70 years of research, much of his theory has withstood well and is still valued. It continues to be popular because it gives us insights and generates new ideas. More recent research has suggested some of his details may be more limited than he thought. However, Piaget’s framework may remain and is still valuable.

Psychologists spend much of their time studying the processes of learning. During much of the 20th Century, psychologists tried to determine similarities between the ways that animals and humans learn. This perspective is called behaviorism. Behaviorists study learning in humans but also in other animals. This research paradigm is primarily concerned with what can be directly measured or observed. It avoids making statements about events that cannot be directly observed, like thoughts, wishes, and feelings.

Behaviorists are not concerned with what the mind does because they believe that the mind cannot be objectively measured. They are doubtful that the mind can ever be scientifically studied at all. However, behaviors can be objectively studied. Their study can tell us very much. Therefore, they focus on behaviors because they are observable.

The behavioral perspective emphasizes how a person behaves or what they do. The roots of behaviorism are largely from physiological laboratories. In Europe, the major contributor was the Russian Nobel Prize winner Ivan Pavlov. Pavlov showed that when a neutral even is paired with an emotional or physically reactive event, the neutral event will eventually “take on” aspects of the emotional event. This is referred to as classical conditioning. It gets this name because it was the first type of conditioning that was discovered. Hence it is “classical” like classical music or classic rock.

Classical conditioning, also called Pavlovian conditioning, pairs a naturally occurring response with a neutral response. Loud noises, obnoxious smells, bursts of light can all become classically conditioned to us (C. S. Hall, Lindzey, & Campbell, 1998).

For example, look at a lemon a few times before you taste the juice. You will find that you start to salivate very quickly when you see the lemon, even if you are not actually tasting the lemon juice. This is an example of classical conditioning. Furthermore, you may even salivate just being in the grocery produce section aisle where lemons are located. This is a process called secondary conditioning.

Try it. It also works well with hot peppers, depending on your experience eating them. However, it will not work with butter or white bread because they do not typically cause people to salivate.

Many types of trauma and addiction are thought to be rooted in classical conditioning. As an example, a person might be hit by a large red car while crossing the street. After this, any red car might make them highly anxious. This experience may generalize to where the accident occurred and even the time of day. This is thought to be how traumas generalize.

Taste aversion is a particular type of classical conditioning that most of us have experienced. We are born with the capacity for taste aversion, but it has to be activated by learning. When you get very sick from eating something, you will not want to eat it again. If you eat food in a particular restaurant and become ill, your experience may generalize. You may want to avoid that restaurant or any place that resembles it. Furthermore, you will not want to eat anything that resembles the food that made you ill. You may even avoid the people associated with the food, such as the people with whom you ate it.

Operant conditioning, a different type of conditioned learning, was discovered before Pavlovian conditioning but gained prominence about two decades later when researched more thoroughly by the American psychologist B. F. Skinner and his many associates (Ryckman, 2004). Operant conditioning occurs when something in the environment or world “operates” on behavior to encourage or discourage it.

Operant conditioning occurs all the time around us. We are operantly conditioning others, even if we do not realize it. For example, when we have a lively conversation with someone, we engage in operant conditioning because we actively talk about specific topics and discourage others. Suppose you have a roommate, brother, or sister, and you avoid or encourage talking about particular topics with them. In that case, you are operantly conditioning them, and you did not even know it.

Stop for a second and think about how many things in the environment operably condition you?

Psychologists have discovered various schedules of reinforcements that act during operant conditioning. These are ways that reinforcements can be timed to change the likelihood that a behavior will change. Some of these are listed below.

|

Figure 2.4 Schedules of Reinforcement https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-psychology/chapter/reading-reinforcement-schedules/

|

Psychologists realize that the best way to change a behavior is to reward or reinforce it when possible. Withdrawing of rewards or negative reinforcement is included in this.

Punishment to change a behavior is usually not as effective as providing rewards. This is true for several reasons.

One reason is that punishment draws attention to negative behavior. The person or animal who performs the behavior observes the punishment. So do other people or animals. Everyone learns what not to do. As soon as the environment changes, they have learned something, usually the wrong thing.

Secondly, punishment almost always causes an excessive emotional response. The emotional response is always a negative one that gets in the way of emotions likely to produce positive behavior. In the case of humans, these include feelings of rationality and future cooperation.

Third, punishment suppresses behaviors, but the behaviors often return after a time. It is a phenomenon seen throughout nature in every animal. Punishment may stop a behavior but remove the punishment, and the behavior will almost always start again.

Punishment may result in quick but generally not long-lasting behavioral changes. It may also make us overconfident about the effectiveness of our interventions. But often, punishment does not work as well as we typically think. This is why psychologists generally do not like to recommend it.

The most effective way to change behavior is ceasing to reward it when possible or to reward alternative behaviors.

Beyond this, behavioral psychologists have also understood that the best way to change behavior is to provide quick and specific feedback. Unfortunately, this is not always possible. This is true for rewards or punishments, although the limitations regarding the effects of punishment still hold true.

In summary, in most situations, the most effective way of changing behavior is to provide immediate rewards when possible and ignore, reframe, or otherwise redirect inappropriate behavior.

The behavioral perspective has been successful in producing various therapies for specific emotional and physical disorders. These include autism, addictions, depression, anxiety, psychological trauma, speech problems, and movement disorders, to name just a few areas. Psychologists and specially trained therapists administer treatments in a variety of settings. They use behavioral principles in their treatments.

The use of behavioral principles is an exciting area in psychology and continues to find new applications.

Psychologist Edna Foa who pioneered Behavioral Treatments for Traumatic Stress and was a Time Magazine 100 Most Influential People CC BY 3.0 CC BY 3.0 File: David Shankbone 2010.jpg

SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY

Towards the last third of the 20th Century, many psychologists realized the much human learning occurred through social interaction. It was not directly reinforced by rewards or punishment. The laws of learning that behaviorists discovered just did not seem enough to account for how people learned in the real world.

Social Learning theorists move beyond behaviorism, studying how people learn from watching others’ behavior (Boyle, Matthews, & Saklofske, 2008). Although many researchers are associated with this perspective, the Canadian psychologist Albert Bandura is perhaps the best known. Bandura showed that many very important human behaviors are not be learned directly through rewards and punishments. Instead, they are modeled by watching others and then imitated. Bandura’s contribution was to show that reinforcement can be vicarious¸which means that it can be learned through observing the behavior of others.A person does not have to be directly rewarded for learning to occur.

Like Behaviroists, Social Learning theorists recognize the importance of the environment. But they also acknowledge the importance of mental states or thinking. Most Social Learning theorists believe that what a person thinks can be as important as what is directly reinforced in the person. In fact, the two are intertwined.

Social Learning theorists also emphasize a person’s perception of the situation. They realize a person can discount rewards or ignore them in ways that might not apply to many other animals. This perspective is very similar to that proposed by Alfred Adler. He believed that people’s perceptions of situations determine their realities.

As an example, people can choose to engage in short-term pains for long-term gains. They can engage in very physically punishing behavior, such as intense exercise training. They can do so if they anticipate the results will be positive. They can also reward themselves with self-talk rather than rely on others complimenting them. People can change, according to Bandura, without overt reinforcement or rewards.

Social Learning theorists are called mutual determinists. Like Adler, they believe that behavior determines thinking and that thinking determines behavior. It works in both directions. A person who does something is likely to think in specific ways. But our thought causes us to act in a particular direction. This gives us two powerful techniques to change behaviors.

The Social Learning perspective is not limited to clinical use. It has a broader application for social justice problems. An example has been the work of psychologist Dr. Jennifer Eberhardt. She is 2014 received a MacArthur Foundation award for her groundbreaking work on racial stereotypes. She has applied Social Learning theory to racism and social justice problems in a way that can help law enforcement and juries act more equitably. What is notable is that even if racial stereotypes are unconscious, they can be challenged and even changed through cognitive and Social Learning techniques.

A type of psychological treatment called Cognitive Behaviorism is closely related to Social Learning theory. Adherents of this treatment recognize the importance of the behavioral perspective and techniques but add more. They see the significant reinforcers of behavior within the person(Hupp, Reitman, & Jewell, 2008). The person has a say in deciding if the situation is reinforcing. In cognitive-behavioral therapy, also called cognitive therapy, the patient or client may learn to reinterpret or reframe adverse life events in a more positive light (C. S. Hall et al., 1998).

Cognitive-behavioral and cognitive therapy have produced successful psychological interventions for many disorders. These interventions have been effective for depression, anxiety, substance abuse, couples therapy, and many other problems. Therapists now know that by changing people’s thinking, they can change their behavior. For example, the cognitive-behavioral treatment of depression may examine the thoughts associated with drug dependence and assist a person in changing them.

The Biological perspective attempts to reduce cognition, behavior, and other psychological processes down to components found in individual biology. Biological perspectives in adolescent psychology have gained a more prominent place in the last 20 years. This is not surprising. During the teen years, the most prominent event is puberty, triggered by biological changes through hormones. The changes are undoubtedly dramatic and notable to everyone, especially the adolescent. Much research has gone into this area. Our knowledge has been furthered in part because we can use animal models to advance our biological and medical knowledge.

One of the more exciting fields today is neuroscience. This field combines chemistry, biology, psychology, and aspects of medicine to understand the brain. The area of neuroscience also uses animal models to investigate the brain. In recent years, advances in neuroscience have given scientists a more detailed understanding of the adolescent brain’s functions. Advances include ways of viewing the brain through time to chart the changes. Other advances involve observing the effects of alcohol and other drugs and addictive behaviors on the adolescent brain.

Neuroscience is closely related to the methods of behaviorism. The scientific rigor, as well as some of the laboratory techniques, are similar. The difference is that new technologies allow science to link brain processes more directly to behavior, a glimpse that previous generations did not have. Behaviorists believed that it was technologically impossible to study the brain. Now we know that in many situations, we now can. With each year, we are finding newer ways of applying technology for this goal. The distinction between these two paradigms has dissolved in many areas.

As outlined in Unit 4, the human brain comprises neurotransmitters and receptors, chemicals, and pathway targets that make us who we uniquely are. Our ability to study these has grown tremendously and will continue to grow.

Until recently, it was thought that the human brain was essentially fixed from early childhood onward. Thus, it was believed that no significant growth occurred. Then it was discovered that in adolescence, a remarkable event took place. A substantial amount of rewiring of the brain was found to be typical during the teenage years. Furthermore, it was found that the brain was more “plastic,” meaning changeable. This was a monumental discovery! As one older textbook said, “You have what you had as a five-year-old.”

Psychologists and neuroscientists still do not fully understand the implications of these findings. But we now refer to the brain as being “plastic” at more extended portions of life. This means that it is changeable, well into later adulthood. This is an essential series of discoveries that overturned much of what we thought was true about how the brain developed.

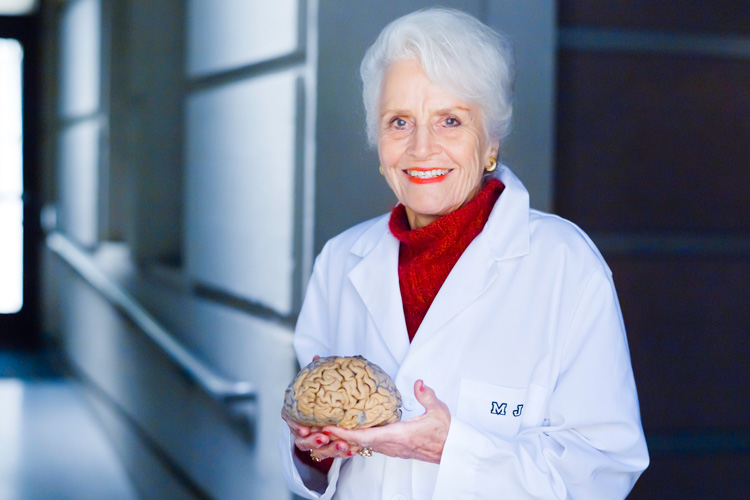

Dr. Marian Diamond, a Researcher who discovered Neuroplasticity and was a founder of the field of Neuroscience. Author unknown CC 3.0

The pace of findings in neuroscience makes it very likely that our understanding of the brain will increase rapidly and dramatically in the future.

Already we see exciting possibilities for new treatments based on the findings of neuroscience. One example is in violence research. Research shows that violent events in childhood (or perhaps adolescence) that occur to an individual accelerate biological aging, including speeding up the onset of puberty (Colich, Rosen, Williams, & McLaughlin, 2020). Exposure to violence also speeds up cellular aging and thins the cortex, a sign of increased aging. Thus, it is possible that by treating psychological traumas, including the traumas of adolescence, we can delay aging or blunt some of its most profound aspects.

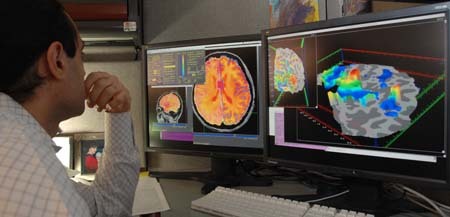

Neuroimaging is a tool to study the brain. Most people are familiar with neuroimaging. CT (computerized tomography) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans are used by physicians and can diagnose many disorders. Researchers use them because these techniques are very good at obtaining pictures of the structure of the brain. However, these are not especially helpful for watching the brain’s processes and how it changes as thoughts occur. These imaging techniques are similar to very accurate but very still snapshots.

Of course, we are very interested in having accurate pictures of the brain when it is still. But we are also interested in the brain when it is active and doing something that we want to study. New methods of neuroimaging make this more possible.

Positron emission tomography scans (PET scan) record blood flow in the brain. In this procedure, researchers inject a safe but slightly radioactive substance into a person’s bloodstream. A radioactive scanner detects the amount of positron radiation emitted from the brain in various areas while performing a psychological test or task. The radioactivity level indicates how much brain activity is occurring in specific regions during these processes.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) also measures the brain’s processes in real-time through blood flow. It uses changes in oxygen levels of the blood as a measure and does not require added radiation. Areas with more blood flow indicate more significant activity.

While these methods are good at identifying brain structures, they also have limitations. It takes time for blood to flow. We may not have a fast enough ability to picture the brain as it makes rapid changes that determine who we are and how we think.

Researcher looking at a brain image

Image: National Institute of Mental Health, CC0 Public Domain, https://goo.gl/m25gce]

Older technology can detect rapid changes in brain functioning. Electroencephalography (EEG) is a technology to measure brain activity in real-time. Electrodes are placed directly on the scalp in various places. A computer records the results. These results can be accurate to a hundredth of a second or faster. Data can be plotted to show brain waves. A limitation of EEG technology is that EEGs are not usually as precise as the PET or fMRI at identifying exact brain locations. This is because they measure multiple areas of the brain simultaneously. Yet, EEGs are extremely useful for some types of research.

Although new methods are being devised to examine the brain, it is still mysterious. However, our knowledge is increasing each year dramatically. As our technology becomes more adept, we can penetrate more into its mysterious functioning. The future of neuroscience, especially in adolescent research, will continue to show progress for many years.

Often closely aligned to the biological paradigm is the evolutionary perspective. This paradigm is rooted in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and natural selection. Researchers emphasize how present-day behaviors are adapted for the survival value of the species. We behavior to pass on our genes to the next generation. We are often unaware of why we act as we do.

Evolutionary Developmental Psychology is a new subfield that applies the evolutionary perspective to human development. Behaviors such as excessive adolescent risk-taking and challenging authority may make more sense from this view. These strategies maximize a person’s likelihood of reproductive success in some situations. Whether they are adaptive for our current culture is questionable and depends on many factors.

In the late 1930s, the psychologist Carl Rogers observed that juvenile delinquents –youths committed into prison for rehabilitation- who felt positive about themselves had a better outcome than those who felt negative about themselves (C. S. Hall et al., 1998). The finding was unusual. According to the existing beliefs, self-rejection should cause criminals to rehabilitate rather than self-acceptance. For almost 50 years, Rogers spent his career attempting to make sense of these findings and determine how we can best help people change. His therapeutic technique, which encourages therapists to listen with genuine empathy, has become one of the most critical tools in treating psychological problems.

Rogers and many others developed an approach called Humanistic Psychology, which emphasized that people have choices. In some ways, it was very similar to Adler’s approach. But in therapy, it was different from traditional methods, where people are often considered passive. Not surprisingly, it emphasized self-acceptance and empathy (Searight, 2016). In addition, Rogers developed a specific type of therapy called Client-Centered Therapy that is widely used by many therapists regardless of their theoretical beliefs. Client-Centered Therapy involves listening to the client and closely reflecting on what they said.

An early proponent of Humanistic Psychology was Abraham Maslow. Maslow met Freud as a young man. He was also briefly a student of Alfred Adler. Maslow is known for the hierarchy of needs usually discussed in every psychology class (Barenbaum & Winter, 2013).

Recent research has discussed that adolescents may seem to lack goals and values. A constant criticism for adolescents’ contemporary education has been that it does not prepare students to think about moral issues. This has been a topic of people from all political spectrums.

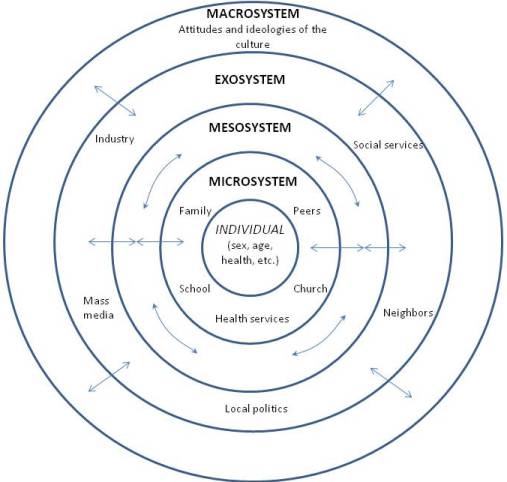

The Ecological Perspective states that a person is a product of their genetics, environment, and interaction at a specific place and time. Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979) suggests that interactions with others and the environment are the keys to development.

Proponents of this perspective believe that we experience multiple environments that may simultaneously interact with each other.

The microsystem, such as a family, is the current environment in which a person exists.

The mesosystem is the interaction of microsystems. An example is an interaction between an adolescent’s home and school or home and church.

The exosystem is an external system that a person is not directly involved but which affects them. An example for an adolescent is a parent’s workplace. Stress at the workplace, such as a moody or mean boss or coworker, can indirectly affect a person’s children.

The macrosystem is the larger cultural context. It includes everything outside of these other systems that might affect an individual. An example is a state or country where politics can affect a young person’s life situation.

Each system has its expectations, roles, and patterns. Bronfenbrenner believed that when the expectations between systems were similar, there tended to be harmony and progress. When rules were different at each level of the system, it was confusing and caused problems. The ecological perspective can also be called a multi-system perspective.

Disruptions to systems are possible at any level. For example, being in a cohort that experienced stress or an economic downturn can significantly affect multiple systems. The stress experienced by people following the terrorist attack of 9/11 or the economic downturn in the Great Recession of 2007-2012 had a substantial impact on some adolescents’ development.

One source of stress that affects systems is the adverse effects of racial and other forms of discrimination. Adolescents from groups that have been historically denied rights are at high risk for problem behaviors. Racism, sexism, and poverty have long-term and confirmed effects on people. These effects may include an impact on the immune system, sometimes many decades later.

The effects of events like the Covid-19 pandemic may be profound. They could likely have a long-lasting impact on adolescents as they transition into young adults and beyond. This event could affect multiple systems. These effects could be both psychological and physical.

The Ecological Perspective This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY

SYNTHESIZING PERSPECTIVES

Different perspectives are sometimes in competition. Are any of these perspectives “correct”? It is easy to look at some of them and say that they are no longer worthy of consideration. But is that a good idea? Is there one best paradigm? This is a very complicated issue, and psychologists disagree.

Sometimes a complex question needs to be addressed from various research traditions. A paradigm is valuable if it helps us generate additional research that allows us greater understanding. It is not beneficial if it interferes with the development of knowledge.

Freud may seem strange but imagine a life where none of his concepts had ever been thought of. How would we go about discussing our feelings, thoughts, and intentions?

How would you analyze adolescent gang membership from each of these perspectives?

What type of problems are best researched from a biological orientation or perspective?

What do you think the strengths and weaknesses are with an ecological perspective?

Which perspective might be more interested in issues of social justice, equity, and fairness? Why?