Introduction to Adolescence

UNIT GOALS

Define adolescence.

Understand why adolescent thinking is different from child and adult thinking.

Define two types of thinking in adolescents.

Discuss the unique problems of adolescent people.

Highlight contributions of neurobehavioral science to the study of adolescent development.

Discuss the unique challenges to contemporary adolescents compared with previous generations.

OVERVIEW OF ADOLESCENCE

Adolescence represents one of the most perplexing periods of human development. It is a time of change. Both brains and bodies are rapidly transforming. People in this age group often try to gain a sense of identity as they experiment with various roles and possibilities. For many people, these changes may be associated with lonely, scary, even dangerous years. Yet this period can also be one of the opportunities and positive experiences.

Adolescence includes the onset of puberty and changes in secondary sexual characteristics. These are defined as physical characteristics developing at puberty which differ between the biological sexes but are not directly involved in reproduction.

However, adolescence is a time for many other changes beyond the obvious and physical. Many of these are psychological and may at first be more subtle. Typically, the individual becomes more autonomous, independent, open, develops more skills, and often anticipates living apart from their family. But by 19 or 20, a person may be quite different from the beginning of adolescence. They look different. Their personalities and interests change. They may have new friends, a new faith, and a different lifestyle.

Regardless, they are still the same person. Almost without exception, if you had a friend or family member you did not see between the ages of 11and 19, you could still identify them again when you reunited. You would recognize most, but not all, of their mannerisms and some, but not all, of their personality traits. Moreover, depending on how well you knew them, you probably would be able to recognize areas where they had changed and how much they had changed.

According to an East African folk tale, the teenage years are curious because we simultaneously change profoundly and stay the same.

Adolescence is also notable because the period carries many risks. The years between ages 13 and 19 are among the most dangerous in a person’s life. This is because people act impulsively, which means acting without thinking. The consequences can be devastating. One reason for the risk is because this period remains one of behavioral experimentation. People try new behaviors, often with unexpected results.

Furthermore, a misunderstanding of risk factors may place adolescents in dangerous situations or encourage them to behave recklessly. As a result, deaths from impulsive actions are often very high in this age group, compared to other ages. These include deaths through accidents, drug and alcohol overdoses, and aggressive behavior.

A common phrase that teenagers tell parents, teachers, and friends after trying a risky behavior is, “I had no idea it would turn out like this.”

The adolescent years are also some of the most precarious for an individual’s mental health. This is because adolescents are exceptionally vulnerable to mental and behavioral disorders (Ahmed et al., 2020). These include bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, substance abuse, depression, and antisocial behaviors. Yet fortunately, most people will make the transition to adulthood safely and in good mental health.

Society is also at risk for the effects of adolescents and their behaviors. In most cultures, adolescents commit a large amount of the total crime. Adolescents are notorious for breaking the rules. Too often, their behavior seems out of control. This pattern has been confirmed at least since recorded history. Yet, there are also many positive influences of large adolescent populations.

The Period of Adolescence

Although the adolescent years are developmentally critical, no one is sure when to say that the adolescent period starts. Unlike childhood, which divides into logical periods, the teenage years have no apparent natural boundaries. Parents and researchers often divide the term “youth” between the prenatal period, before birth, the newborn period, early childhood, middle childhood, and later childhood. Teenage years can be defined by a number, 13 to 19. However, no natural landmarks exist for the term “adolescence.” No one knows when it actually starts. Any divisions are somewhat subjective and based on social factors that change from culture to culture (Lewis, 2007).

Nor can people agree on when adolescence ends. An answer to this question involves a mixture of biology and cultural norms. A few cultures do not have a concept of adolescence at all. A person passes through the beginning of puberty and then is considered a full adult. Some cultures consider people as adults once they meet specific phases in the maturational process. An example might include when females reach an educational milestone or when males have completed a successful game hunt. Others treat adolescents more like younger children than soon-to-be adults. Different cultures have different needs, and this is reflected in their social systems.

In the United States, we usually do not make consistent divisions between the phases of adolescence. We informally recognize that the older teenager is much closer to being an adult. However, there is often little gradual transition to adult status. The law often offers us little guidance (Klimstra, Borghuis, & Bleidorn, 2018).

The legal definitions of when adolescence ends vary throughout the world. Many societies grant late teenagers limited autonomy at around age 18. For example, in the United States, most people of this age are allowed to quit school, end parental relations, get married without parental or court consent, and enter into most legal contracts. They can also vote, visit a health care provider, and have complete control over their medical and educational records.

However, many societies do not allow an 18-year-old to be “fully adult.” For example, in the United States, people at this age are not allowed to purchase alcohol or legally gamble in many jurisdictions. Loosening alcohol restrictions, attempted in the 1980s, was rolled back after higher alcohol-driving fatalities occurred among young people.

Prohibition against alcohol use by 18-year-olds is less stringent in other areas of North America and Europe than in the United States. However, even older adolescents are restricted from nicotine use in most places in the United States and elsewhere.

In countries other than the United States, various pathways are associated with the teenage years. In some, usually those less economically well-off countries, adolescents must seek a living to support the family. This role is avoided as long as possible, often deferred to allow students optimal opportunities for education. In some countries, the period of adolescence ends abruptly with compulsory military service for everyone. In others, it ends with marriage, which may be arranged.

There is also variation in physical development. Almost without exception, everyone eventually goes through puberty, the biological process of sexual maturation during adolescence. However, the timing is often different. In addition, cultural factors appear to have a substantial influence. The process of puberty is discussed in Unit 5.

Units 2 and 4 discuss the field of neuroscience and its application to adolescence. Neuroscience is the scientific study of the functioning of the brain. Until relatively recently, researchers in the area of neuroscience were not primarily concerned with adolescent development. The belief was that teenage behavior was mainly learned or caused by social factors. Neuroscience research now shows that the adolescent brain experiences dramatic change during this critical period. It is very sensitive and capable of substantial rewiring. However, this makes adolescents especially vulnerable to trauma and adverse experiences that may occur during this period. Although adolescents are very resilient, there may be periods when they are very susceptible to stress, trauma, and a lack of environmental control.

Cognition During Adolescence

Findings from psychology and from neuroscience help us determine how adolescence are different from children or adults. One area is cognition.

Cognition involves the process of how we think. Adolescents think about the world differently than both younger children and adults. Understanding of the world in early adolescence may be very selfish or self-focused. Through time, the content and structure of cognition, meaning what and how people think, changes to be more inclusive of others. Adolescents also learn to think more logically. They develop what the cognitive psychologist Jean Piaget called formal operations or formal operational thought. This is discussed in Unit 2.

Formal operational thought is the last of Piaget’s concepts to develop. This is the most sophisticated type of thinking that humans typically have. It involves problem-solving. Piaget showed that adolescents demonstrate an increasing ability to develop hypotheses about the world and use deductive reasoning to test them. Their thinking becomes more logical than previously. This sets them apart from even their most intelligent but younger peers.

While adolescents can be more logical, their thinking is often dominated by a more emotional type of decision-making. Other theories describe the balance between two kinds of thinking that commonly occur during adolescence. One type of thinking is intuitive and reactive. This type of thinking tends to be more emotional and less logical. This thinking style is necessary for us to make quick decisions that involve “gut reactions.” The other type of thinking is more analytic and slower to activate. This second type of thinking is associated with more deliberate problem-solving. While both types of thinking increase during adolescence, the former tends to dominate during the earlier years. Emotional thinking is quicker than slower deliberation and often seems more satisfying over the short run.

Balancing out the two different thinking styles may take a long time to learn. The proper balance is difficult to develop. Some people never reach the goal and are dominated by one type throughout life. Some people never seem to strike a consistent balance and go from one extreme to another. But why do many adolescents have trouble attaining the balance?

This is an area where the field of neuroscience can help us understand adolescent behavior. Findings from neuroscience suggest that adolescent thinking is characterized by the more rapid development of the brain’s area known as the limbic system and slower growth of the prefrontal cortex (Gupta & Gehlawat, 2020). The limbic system is part of the brain is one of the areas that cause emotions. The prefrontal cortex is one central area that puts the breaks on emotions. In simpler terms, the adolescent brain is more wired to feel emotions and not necessarily inhibit or stop them.

Other research has shown that this is specifically true for one type of feeling dominated by social emotions. Adolescents are hardwired to react with feelings in situations that involve other people. Furthermore, research has shown that this tendency to respond emotionally increases in group situations. This may explain why adolescents often feel they are susceptible to peer pressure.

Adolescents are often thought to be especially sensitive to rewards. They become particularly sensitive to rewards in the presence of peers. Simultaneously they also become more insensitive to the possibilities of future punishments when peers are present. This can lead to a variety of poor choices often associated with “dares” made by friends. A reason for this may be that the brains of adolescents are wired to act this way. As a result, we may take more chances when others are present. From an evolutionary sense, this might make sense. However, it is easy to see how this type of wiring might lead us into trouble today.

Adolescence and Innovation

Although adolescence is a risky period, it is also one of potential change and innovation. Teenagers are socially prepared and biologically designed for novelty. But, not surprisingly, adolescents are, as a group, incredibly creative. This has been true throughout recorded history. It is just as accurate today.

Adolescents constantly produced innovations. This has been true through history and shows no sign of slowing down. Fashions, music, even the humor of just a few years ago may seem highly dated by now. Unfortunately, this has always been the case and probably always will be. Think back at your own teenage years and compare them to today. You may see changes that are beginning to emerge.

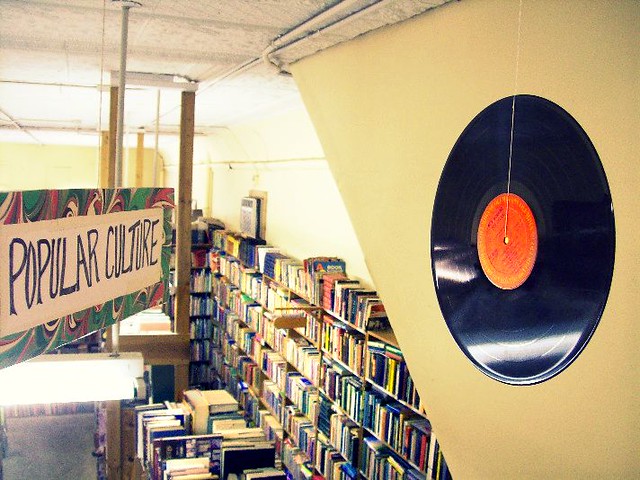

Regardless of other factors, the adolescent years are critical because of adolescents’ contributions to our shared national and world cultures. Popular culture and many other innovations would not exist in their present form without the continued inspiration and ideas of younger people. Developments in fashion, popular music, art, gaming, cooking, and many other areas frequently start with adolescents. While this has been true in many cultures and countries, it is especially true in the United States and Europe. This level of accelerated creativity in younger people is now increasingly observed in Asia and Africa. The impact of cultural innovation can be shared worldwide through the internet.

Regardless of other factors, the adolescent years are critical because of adolescents’ contributions to our shared national and world cultures. Popular culture and many other innovations would not exist in their present form without the continued inspiration and ideas of younger people. Developments in fashion, popular music, art, gaming, cooking, and many other areas frequently start with adolescents. While this has been true in many cultures and countries, it is especially true in the United States and Europe. This level of accelerated creativity in younger people is now increasingly observed in Asia and Africa. The impact of cultural innovation can be shared worldwide through the internet.

Adolescents have always had the drive to do something new and exciting. We are beginning to see the adolescent drive for novelty in many more areas than popular culture. Innovations in technology and even life sciences are profiting from ideas generated by adolescents. The internet allows the talent of younger people to be noticed in ways that it previously was not. This tendency will surely increase in the next quarter-century as reliance on newer technology increases.

THE HISTORY OF ADOLESCENCE

Many people believe that adolescence as a separate and definable age period started at the turn of the 20th Century. American psychology, in particular, paid a great deal of attention to this age group during this time. This attention was in part related to the rapid industrialization of America. As a result, young, more urbanized, often immigrant youth displayed different problems than those from more rural backgrounds. Poverty, overcrowding, and lack of opportunity made problems of this age group more frequent and observable.

In 1904, psychologist G. Stanley Hall wrote a very influential two-volume text on adolescents. This was one of the first scholarly accounts on the topic. He promoted the concept that adolescence was a time of extreme difficulty where behavioral problems were expected. Almost 120 years later, some of his ideas have withstood. Hall’s account is still influential.

Hall defined the adolescent years as the ages 14 and 24. He believed that adolescence was essentially a modern phenomenon, mainly related to industrialization. At best, this is only partly true. Industrialized societies typically pay more attention to the teenage years and the problems of adolescents. However, the often difficult period between childhood and adulthood has rarely escaped the interest of any social group.

Hall’s work was groundbreaking for its time (Lerner & Steinberg, 2004). What is also evident from his work is how he made claims that sometimes lacked adequate research. Many of his conclusions, for example, that boys and girls should be separated in school during their adolescent years, seem quaint. Some were based on speculation. Psychologists today require that theorists support their beliefs with research, which was lacking in Hall’s day. As we will learn in Unit 2, research is essential for scientific progress. Unfortunately, many of Hall’s assertions were, by our current standards, not supported by necessary evidence.

European and Eurasian societies were keenly aware of children’s difficulties as they transition into their teenage years (Dennis, 1946). For example, the writings of the ancient Persians and Greeks, for example, over 2400 years ago, offer thoughtful advice to parents of adolescents. In the early Christian era, the Romans promoted adolescents as an intellectually active time where students were encouraged to challenge adults. Teenagers, especially males, were given some degree of freedom.

But as the Dark Ages descended on Europe, adolescence as a distinct age group seemed to vanish. Economic conditions often forced children to grow up quickly and assume adult roles, even before puberty. The appallingly high death rates from war, plagues, and constant famines solidified customs where children became adults at a young age. However, there were variations in this pattern based on economic conditions.

In Africa, as in Europe and Asia, different societies had different needs. In some areas, often those with high infant mortality, children became adults with little preparation. In others, adolescence was part of a prolonged initiation period, not unlike Western cultures today. During these periods, young people learned complex skills, mastered complicated ways of future social interaction, and learned about rich oral or other cultural histories.

In Asia, there was also tremendous variation in how young people in the teenage years were viewed. Some societies afforded children an extended adolescent period comparable to today. Some compacted adolescence into an extended childhood and then into early adulthood. Differences were based on social realities, economic and environmental conditions, customs, and traditions.

Native people in the Americas were not a distinct group. No generalizations are possible. However, groups that were primarily hunters and gatherers had less of an adolescent period. They often needed to replace their members quickly, with the youngest and most robust. Groups that had more specialization of labor or were more urban dwellers had rites of passage associated with adolescence. This occurred after members had specialized periods of training. This is not different from today.

In general, as society has developed more specialized roles, a more extended period of adolescence is required. Not surprisingly, this means that the definition of adolescence can and does change through time. For example, once adolescence was restricted to the early teen years and essentially over by ages 16 or 17. With work and life demanding increasing specialized knowledge, perhaps the future of adolescence will be one of progressive length well into a person’s early or mid-20s or beyond.

Variations and Common Paths in Adolescence

There is often significant variation in maturation rates in adolescents. Boys are usually slower to develop. Some girls grow quicker than others. What is normal for one person in one society or group may not be typical or average for another. However, despite the tremendous differences, there are often some common patterns.

Many of these standard features are psychological. For many people in our culture, the early teen years include an increased awareness of others and enhanced self-consciousness. As a result, adolescent people may be incredibly self-critical of their own appearance, style, and looks. Consequently, they may be vulnerable to eating disorders such as bulimia or anorexia. They may also be likely to become depressed, especially when comparing their appearances to peers, or more likely, distant media icons or social media influencers.

At the same time that adolescents are increasingly self-critical, they may suffer gaps in monitoring their own behavior. They are likely to be more impulsive and act more without thinking. Paying attention, especially to activities that they do not enjoy, may become more complex. Adolescent teens may find displays of sarcasm and bullying are rewarded. They may express these behaviors among themselves or in other groups. When combined with the difficulties in monitoring behaviors, parents and siblings may be very unhappy with the person they see temporarily emerging during these times.

In our society, the teenage years are characterized by a tendency to form elaborate personal narratives or life stories. As adults, we develop stories or accounts to live by. These are often rooted in what we did during our teen years, where we tried on several different roles. A teenager may imagine herself to be an internet influencer, an athlete, an entrepreneur, and a caring medical professional, all in the span of a brief period. Various approaches to faith, politics, and fashion may appear in succession. They seem to try on what fits their experience, personality, and most current worldview.

Eventually, the person finds a role and a self that fits the best. They may carry this role throughout the rest of their life. They may discard it for a better fit if one comes along. They may develop their personality further and find they have no choice but to move on. The adolescent years can afford this flexibility in a way that other periods often cannot.

William James, who many people consider the founder of American psychology, believed that the adolescent years were necessary for trying on various hypothetical selves. He noted that we can experiment with possible selves because we have lots of imagination during these years. We can pretend. Adolescents find that they can suddenly think hypothetically about the world, imagining “as if.” To outsiders, this may not make sense, but to the adolescent, it is perfectly logical. A young person can behave one way with friends but have entirely different values while another group of friends. They may have different values and behaviors with parents or family and not feel ungenuine or hypocritical. There is no other time in life that allows so much flexibility of roles.

Despite seeing the teenage years as problematic, we also portray them as intense fun and enjoyment. This is a stereotype in the media that goes back to before World War II. Yet data does not support this. In the United States, the adolescent years are not necessarily the happiest. Longitudinal studies- meaning those conducted through time on the same people- show that many people rate their least enjoyable times in life as their middle teen years. However, people report increasing levels of happiness from then on, at least on average. This trend continues well into a person’s 70s or even into older ages.

This is welcomed news for anyone who had a rough teenage experience. Life should get better. Again, these are averages, and there are tremendous variations. (If you had many unhappy experiences in your teen years which affect your present life, you might wish to discuss them with a mental health professional. Mental health treatment is helpful for many people.)

Specifically, for groups (though not necessarily true of any particular person), we can see lifelong patterns that bear this out. Neuroticism, a personality trait usually thought of as the tendency to experience negative emotions reaches its lifetime height in most people’s middle teen years. The trait of Conscientiousness, which is defined as the tendency to enjoy and want to do a good job, often reaches its lowest point in the teen years, again for most people. This combination of high negative emotions and a low desire to do a good job might predict unhappiness.

On the other hand, Openness to Experience, a personality trait associated with creativity and acceptance of new ideas, reaches its high point in the late teen years. This helps explain why adolescents are usually at the forefront of music, fashion, and media. Unit 6 will discuss these traits more fully.

In most industrial countries, the primary activity for adolescence is attending school. Unfortunately, adolescents are often disengaged from their primary activity, finding it unattractive, dull, and a waste of time. Only about 20% of young people note that they are fully engaged in school. This figure has been relatively consistent through the years. School engagement correlates with positive achievement and college attendance. Unfortunately, the majority of adolescents do not like school, at least not much.

Many people see their high school years as unproductive and full of anxiety. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA

Many late-age teenagers or emerging adults look back and see their intermediary or middle and high school years as academically unproductive. This has held true for every recent generation. People realize these school years are a time of possible anxiety and depression for many students. Yet meaningful school reforms still have not been forthcoming. Very few people are happy with the quality of middle and high school education. Yet, no one has an acceptable improvement plan.

Some adolescents believe that their middle and high school years are a time of particular personal struggle. There are often few social diversions for those who do not like or excel in sports, especially in rural and more impoverished communities. For adolescents who are not extroverted nor sociable, schools may offer few rewarding options. Moreover, many latter-age teens must work in jobs to bring in needed income, making participation in co-curricular activities difficult or impossible.

As one 20-something said about his high school years in a large suburban high school, “I thought it was supposed to be a fun time. It wasn’t. I thought I would learn a lot. I didn’t. And a couple of years after I graduated, I found out everyone pretty much had the same miserable, lonely, anxious experience.”

Public Perception of Adolescence

While many people believe their own middle and high school years were unhappy, most people believe that others were happier during this period than themselves. This is because, in time, unpleasant memories fade, painting a more optimistic portrait for memory.

The farther we get from our adolescent years, the happier they become to us. This is because we tend to forget the unpleasant experiences, stress, embarrassment, difficulties, and awkwardness. In other words, we may actually look back and remember our adolescent years as actually better than they were.

Attitudes about adolescence by the general population have always been complex. These attitudes usually come from a blend of optimistic recall about personal experiences, friends and family accounts, and more negative media portrayals of “kids today.” As a result, many people have a positive memory of this period in their own lives that may not be accurate.

Many people, including many psychology students, measure current adolescents’ behavior against their own positive memories. Depending on how selective their memories are, adolescents today may seem less engaged, more emotional, less headed for a bright future, or massively less respectful. As we age, we tend to remember our “best teenage selves” and compare them to current adolescents engaged in everyday lives or the “bad” behavior that makes the newspapers. It is not a fair comparison.

The media, particularly social media, typically does not focus on the positives. Young people who stand out negatively from the social norm are more likely to be newsworthy. This gives the impression of an ongoing adolescent crisis or sudden behavior changes unknown in the past. This pattern may make it look like young people are undergoing social upheaval and are in constant turmoil. This behavioral exaggeration is entirely untrue. By almost every measurable indicator, today’s young people are more socially positive than many previous generations. They are less violent, less likely to engage in drug and alcohol use, less sexually active, and less likely to have behavioral problems. They are more likely to volunteer, value their families, plan for the future, and save money. However, this is not the perception or the stereotype that the media and other sources portray.

About 70% of adolescents report that their family interactions are mainly positive. More than three-quarters enjoy being with their parents or parent figures and their families. While this number is lower than during childhood, it is remarkably higher than observers might think. Moreover, it runs against the stereotype that adolescents dread and despise their parents and families.

New Challenges For Contemporary Adolescence

Each generation believes that they possess unique challenges that distinguish them from previous groups. While the current generation is no exception, there are many reasons present-day adolescents certainly face unique challenges that other generations did not.

One set of risks and challenges is the dangers and promises from the internet. On the other hand, the internet and the digital world have opened up tremendous opportunities for creativity and learning. Changes have occurred so dramatically that some people forget the speed at which this happened.

We are increasingly involved in a rapidly shifting digital culture. Each generation now finds the internet has a deeper footprint. New platforms and their unexpected benefits and problems arise quickly, and the life complications become more entangled. Promises, possibilities, and threats not dreamed of a few years ago are constantly faced by teens. Go back just a few years to see how much social media has changed. In fact, social media has changed to the point that adolescents frequently find the technology portrayed in television and films from even a few years ago almost laughable and quaint.

Researchers have noted that we do not know how rapidly the pace of these changes will persist. However, they will continue to offer both opportunities and disruptions. Adolescent culture evolves quickly in response to technology changes, usually consistently outstripping the larger society’s capacity to respond. Adolescents develop their own rules of media interaction, their own preferences, and in some cases, entire subcultures. No one can see the future well enough to know if future trends have a dangerous side.

For the entire world, the Covid-19 pandemic was a chaotic disruption. Everyone alive was affected by the virus in some way. This means that the results were almost unpredictable but that they had profound consequences. While most adolescents escaped the most devastating effects of illness from the virus, the pandemic’s psychological disruptive impact may continue for years.

By the end of the teenage years, people in our society are supposed to know how they support themselves and transition into adulthood. Adolescence cannot go on forever. This is society’s consistent message and game plan. Unfortunately, this type of knowledge was delayed by Covid-19 just as it was delayed by the Great Recession of 2008-2013 and previous economic downturns. This is but one reason that unplanned events are so difficult for adolescents. They disrupt the social transitions that typically occur during this period.

Psychologists and other behavioral and social scientists will have much to study in the future as the pandemic’s psychological effects continue to ripple through society. What is clear is that there may be no easy roadmap to recovery when rituals are upended, even briefly.

A Look Into the Future

Recently there have been open divisions in North American and European society regarding political affiliations and dissatisfaction with democratic institutions. In a relatively short time, conspiracy theories concerning a variety of topics have become common. An anti-science agenda has arisen from many political areas. There are cynicism and doubts about the government and the future. None of this was the fault of adolescents. However, it is the world in which young people must live.

There is also the realization by many adolescents in the United States and elsewhere that institutional racism, sexism, homophobia, and classism have existed for too long. There is the feeling among many young people that these problems are not being addressed satisfactorily. Many adolescents are tired of a world that promises changes but consistently fails to deliver.

There is also valid concern regarding climate change. Climate change has been occurring and is undeniable. Strong evidence shows it is caused by human behavior. According to most experts, the atmosphere is heating up at an unsustainable rate. Adolescents live in a world where many species are beginning to disappear. A no-return point may be reached, well within the lifespan of today’s adolescents. As in few times in the past, adolescents face a potentially bleak future.

Each generation thinks of themselves as unique. Adolescents living in the second decade past the millennium are no exception to this thinking. Still, they really are faced with different challenges beyond even these threats to survival.

Changes in the digital age have occurred very quickly, in fact at a disruptive pace. Innovations, such as online learning, social media, digital streaming, smartphones, even texting, are recent. Perhaps we should be optimistic at the rate of technological changes. But many people are worried about the consequences. Everyone these days seems wired to their devices. We do not know how this will affect future development.

Tremendous health care disparities across communities continue in the United States, and they also continue to increase. Adolescents see wealthier people having access to better care. People unfortunate enough to be born poor often have less essential medical resources. They often see no rational reason for this. Such a situation traps people in the likelihood of poverty before they are born.

Economic inequalities have been part of the American landscape since long before the country’s inception. Many argue that they are necessary to fuel competition. Others point out that they have increased dramatically during the past 30 years while American competitiveness has decreased. These are the concerns that younger people now have to face.

Most adolescents realize that equitable internet access is not available to everyone. Unfortunately, internet bandwidth is still limited for people without access in many areas, including lower economic status, minorities, rural dwellers, and many others. This digital divide separates many people in North America from other parts of the world and increases disparities.

Is the World Improving for Adolescents?

It is common for adolescents to wonder if their world is much better than their parents’ or grandparents’. This is a complex question without easy answers. However, there is reason to believe that things may be getting better. Compared to people living 40 or 50 years ago, adolescents may have many more possibilities in life. Many, though not all, have access to more technology, maybe sharing in more affluence, have better health, and enjoy an overall higher standard of living.

Some of today’s adolescents express more concern about racial and ethnic diversity than in previous generations. There is evidence that racial issues are discussed more openly by adolescents than their parents. Whether we have made any actual progress in social change is uncertain. Some people argue we have, while others point to poverty and social failure and disagree. Laws exist that promise more equity, although significant gaps remain in critical areas of equality. At least, some people say, we are having a dialogue. For many, the discussion has been most thoughtful because of adolescent input.

There is evidence that today’s adolescents are being exposed to a more diverse world. Textbooks once reflected a view that neglected our culture’s complexity. These books ignored people who were different. Those slighted often included people of color, single parents, people with diverse physical or mental needs, gays, lesbians, transgender people, and usually anyone who did not fit a stereotype of ideal American life. These trends are starting to change.

Perhaps related to this, today’s adolescents are growing up in a culture that strives to decrease the stigma from psychological and psychiatric disorders. The adolescent-oriented media now openly discusses addiction, bulimia, anxiety, depression, and suicide. These were once considered too “upsetting” topics for public discussion, especially for adolescents. Whether many young people themselves are opening up to these issues remains unknown, but hopeful signs are evident.

Gay, lesbian, and transgender issues are more openly discussed in some areas. A generation ago, it was not uncommon for LGBTQ+ communities to be openly targeted for ridicule by teachers and fellow students. Violence, though still too frequent, was much more common. Social exclusion continues, regrettably, but is not official policy.

People with different ability needs are perhaps more accepted than in previous generations. Many people realize that the concept of disabilities exists on a spectrum. They are not “all or none.” Disabilities are not necessarily lifelong or all-encompassing. Some conditions labeled as disabling may even be seen as a chance for the individual to develop their other strengths and find alternative abilities.

The overall philosophy has shifted from separating people with diverse abilities from the mainstream to allowing and encouraging them to reach their maximum potential. For example, cartoons that feature adolescent characters now show people in wheelchairs or with prosthetic limbs, reflecting reality. This is something that did not occur consistently several years ago.

We believe that the next decades in adolescent research will produce remarkable insights. One reason is that society is experiencing increasing tolerance. But, unfortunately, the history of behavioral science indicates that acceptance almost always comes before progress and understanding.

Yet another reason for optimism is the numerous advances in science associated with adolescent research. Psychologists and other scientists now understand considerably more about the neuroscience of adolescence. During most of the 20th Century, the brain was very much a mystery. Slowly, however, the “black box” of the brain, as earlier psychologists labeled it, is beginning to give up secrets. Recent discoveries have included that portions of the adolescent brain can rewire and reorganize. This will be discussed in Unit 4. We also know that the teenage prefrontal lobes, also described in Unit 4, are not finished development until well into a person’s mid-twenties.

Perhaps a broader reason is that science is becoming more critical of itself. It is challenging even its most basic assumptions. We have already put aside some of our false notions, mainly because we have insisted on a better quality of scientific evidence. The importance of research will be discussed in Unit 2.

Regardless, these are exciting times for Psychology and exciting times for the study of adolescent behavior. This is a field where you can be a contributor. You can be part of the future.

Critical Thinking

How was your adolescence different from that of people your parents’ age? Your grandparents’ age?

Why does each generation seem to feel that current adolescents are acting uncontrollably and are in a crisis? Is there any truth to these statements?

Do you think that the period associated with adolescence starts too early? Does society force young people into a role when they are not ready? Why or why not? When should adolescents be said to end?

Look back on your life at something that you or your friends did in your adolescent years that was creative. What do you think helped the process? What could help make young people more creative?

Based on your experience, or perhaps the experiences of your friends, how could we make social media a more positive and safer experience for adolescents?