Social and Emotional Development

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Compare Erikson and Marcia’s Theories

- Explain Identity and Self-concept

- Summarize the Stages of Ethnic Identity Development

- Explain the Development of Gender Identity

- Summarize Sexuality Identity and Orientation

- Describe Antisocial Behaviors

- Explain the Developmental Stage of Emerging Adulthood[1]

Adolescents continue to refine their sense of self as they relate to others. Adolescent’s main questions are “Who am I?” and “Who do I want to be?” Some adolescents adopt the values and roles that their parents expect of them. Other teens develop identities that align more with the peer groups rather than their parents’ expectations. This is common as adolescents work to form their identities. They pull away from their parents and the peer group becomes very important (Shanahan, McHale, Osgood, & Crouter, 2007). Despite spending less time with their parents, most teens report positive feelings toward them (Moore, Guzman, Hair, Lippman, & Garrett, 2004). Warm and healthy parent-child relationships have been associated with positive outcomes for the adolescent, such as better grades and fewer school behavior problems, in the United States as well as in other countries (Hair et al., 2005).[2]

ERIK ERIKSON – THEORY OF PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Erikson proposed that each period of life has a unique challenge or crisis that a person must face. This is referred to as a psychosocial development. According to Erikson, successful development involves dealing with and resolving the goals and demands of each of these crises in a positive way. These crises are usually called stages, although that is not the term Erikson used. If a person does not resolve a crisis successfully, it may hinder their ability to deal with later crises. For example, an individual who does not develop a clear sense of purpose and identity (Erikson’s fifth crisis – Identity vs. Role Confusion) may become self-absorbed and stagnate rather than working toward the betterment of others (Erikson’s seventh crisis – Generativity vs. Stagnation). However, most individuals are able to successfully complete the eight crises of his theory.[1]

Identity vs. Role Confusion

Identity vs. Role Confusion is a major stage of development where the child has to learn the roles he will occupy as an adult. In adolescence, children (ages 12–18) face the task of identity vs. role confusion. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of fidelity. Fidelity involves being able to commit one’s self to others on the basis of accepting others, even when there may be ideological differences. According to Erikson, an adolescent’s main task is developing a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, most adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit; they explore various roles and ideas, set goals, and attempt to discover their “adult” selves.

Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. When adolescents are apathetic, do not make a conscious search for identity, or are pressured to conform to their parents’ ideas for the future, they may develop a weak sense of self and experience role confusion. They will be unsure of their identity and confused about the future. Teenagers who struggle to adopt a positive role will likely struggle to “find” themselves as adults.[2]

Erikson saw this as a period of confusion and experimentation regarding identity and how one navigates along life’s path. During adolescence, we experience psychological moratorium, where teens put their current identity on hold while they explore their options for identity. The culmination of this exploration is a more coherent view of oneself. Those who are unsuccessful at resolving this stage may either withdraw further into social isolation or become lost in the crowd. However, more recent research suggests, that few leave this age period with identity achievement, and that most identity formation occurs during young adulthood (Côtè, 2006).[3]

In this video, Dr. Boise briefly describes Erikson’s task for adolescence, identity development.

JAMES MARCIA – THEORY OF IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT

One approach to assessing identity development was proposed by James Marcia. In his approach, adolescents are asking questions regarding their exploration of and commitment to issues related to occupation, politics, religion, and sexual behavior. Studies assessing how teens pass through Marcia’s stages show that although most teens eventually succeed in developing a stable identity, the path to it is not always easy and there are many routes that can be taken.

Some teens may simply adopt the beliefs of their parents or the first role that is offered to them, perhaps at the expense of searching for other more promising possibilities (foreclosure status). Other teens may spend years trying on different possible identities (moratorium status) before finally choosing one.

Marcia identified four identity statuses that represent the four possible combinations of the dimension of commitment and exploration.

Table 15.1 Identity Status[1]

Identity Status

Description

Identity-Diffusion status is a status that characterizes those who have neither explored the options, nor made a commitment to an identity.

The individual does not have firm commitments regarding the issues in question and is not making progress toward them. Those who persist in this identity may drift aimlessly with little connection to those around them or have little sense of purpose in life.

Identity-Foreclosure status is the status for those who have made a commitment to an identity without having explored the options.

The individual has not engaged in any identity experimentation and has established an identity based on the choices or values of others. Some parents may make these decisions for their children and do not grant the teen the opportunity to make choices. In other instances, teens may strongly identify with parents and others in their life and wish to follow in their footsteps.

Identity-Moratorium status is a status that describes those who are exploring in an attempt to establish an identity but have yet to have made any commitment.

The individual is exploring various choices but has not yet made a clear commitment to any of them. This can be an anxious and emotionally tense time period as the adolescent experiments with different roles and explores various beliefs. Nothing is certain and there are many questions, but few answers.

Identity-Achievement status refers to the status for those who, after exploration, have made a commitment.

The individual has attained a coherent and committed identity based on personal decisions. This is a long process and is not often achieved by the end of adolescence

The least mature status, and one common in many children, is identity diffusion. During high school and the college years, teens and young adults move from identity diffusion and foreclosure toward moratorium and achievement. The biggest gains in the development of identity are in college, as college students are exposed to a greater variety of career choices, lifestyles, and beliefs. This is likely to spur on questions regarding identity. A great deal of the identity work we do in adolescence and young adulthood is about values and goals, as we strive to articulate a personal vision or dream for what we hope to accomplish in the future (McAdams, 2013).[2]

To help them work through the process of developing an identity, teenagers may try out different identities in different social situations. They may maintain one identity at home and a different type of persona when they are with their peers. Eventually, most teenagers do integrate the different possibilities into a single self-concept and a comfortable sense of identity (identity-achievement status). For teenagers, the peer group provides valuable information about the self-concept. For instance, in response to the question “What were you like as a teenager? (e.g., cool, nerdy, awkward?),” posed on the website Answerbag, one teenager replied in this way:

I’m still a teenager now, but from 8th-9th grade I didn’t really know what I wanted at all. I was smart, so I hung out with the nerdy kids. I still do; my friends mean the world to me. But in the middle of 8th grade I started hanging out with which you may call the “cool” kids…and I also hung out with some stoners, just for variety. I pierced various parts of my body and kept my grades up. Now, I’m just trying to find who I am. I’m even doing my sophomore year in China so I can get a better view of what I want. (Answerbag, 2007). What were you like as a teenager? (e.g., cool, nerdy, awkward?). (Quoted from dojokills on http://www.answerbag.com/q_view/171753)[3]

A big part of what the adolescent is learning is social identity, the part of the self-concept that is derived from one’s group memberships. Adolescents define their social identities according to how they are similar to and different from others, finding meaning in the sports, religious, school, gender, and ethnic categories they belong to.[4]

|

|

|

|

In this video, Dr. Boise briefly reviews Marcia’s identity statuses.

DEVELOPMENT OF IDENTITY AND SELF CONCEPT: WHO AM I?

Developmental psychologists have researched several different areas of identity development for adolescence and some of the main areas include:

In this video, Dr. Boise briefly outlines multiple areas of identity.

Religious Identity

The religious views of teens are often similar to that of their families (Kim- Spoon, Longo, & McCullough, 2012). Most teens may question specific customs, practices, or ideas in the faith of their parents, but few completely reject the religion of their families.

|

|

|

|

Political Identity

The political ideology of teens is also influenced by their parents’ political beliefs. A new trend in the 21st century is a decrease in party affiliation among adults. Many adults do not align themselves with either the democratic or republican party, but view themselves as more of an “independent”. Their teenage children are often following suit or becoming more apolitical (Côtè, 2006).

Vocational Identity

While adolescents in earlier generations envisioned themselves as working in a particular job, and often worked as an apprentice or part-time, this is rarely the case today. Vocational identity takes longer to develop, as most of today’s occupations require specific skills and knowledge that will require additional education or are acquired on the job itself. In addition, many of the jobs held by teens are not in professions that most teens will seek as adults.

Gender Identity

This is also becoming an increasingly prolonged task as attitudes and norms regarding gender keep changing. Societal views on the roles appropriate for particular genders are evolving. Some teens may foreclose on a gender identity as a way of dealing with this uncertainty, and they may adopt more stereotypic male or female roles (Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013). We will be looking more closely at gender identity later in the chapter.[1]

Self-Concept and Self-Esteem

In adolescence, teens continue to develop their self-concept. Their ability to think of the possibilities and to reason more abstractly may explain the further differentiation of the self during adolescence. However, the teen’s understanding of self is often full of contradictions. Young teens may see themselves as outgoing but also withdrawn, happy yet often moody, and both smart and completely clueless (Harter, 2012). These contradictions, along with the teen’s growing recognition that their personality and behavior seem to change depending on who they are with or where they are, can lead the young teen to feel like a fraud. With their parents they may seem angrier and sullen, with their friends they are more outgoing and goofy, and at work they are quiet and cautious. “Which one is really me?” may be the refrain of the young teenager. Harter (2012) found that adolescents emphasize traits such as being friendly and considerate more than do children, highlighting their increasing concern about how others may see them. Harter also found that older teens add values and moral standards to their self- descriptions.

|

|

As self-concept develops, so does self-esteem. In addition to the academic, social, appearance, and physical/athletic dimensions of self-esteem in middle and late childhood, teens also add perceptions of their competency in romantic relationships, on the job, and in close friendships (Harter, 2006). Self-esteem often decreases when children transition from one school setting to another, such as shifting from elementary to middle school, or junior high to high school (Ryan, Shim, & Makara, 2013). These decreases are usually temporary, unless there are additional stressors such as parental conflict, or other family disruptions (De Wit, Karioja, Rye, & Shain, 2011). Self-esteem rises from mid to late adolescence for most teenagers, especially if they feel confident in their peer relationships, their appearance, and athletic abilities (Birkeland, Melkivik, Holsen, & Wold, 2012).[2]

DEVELOPMENT OF GENDER IDENTITY

“Sex,” refers to physical or physiological differences between males, females, and intersex persons, including both their primary and secondary sex characteristics. “Gender,” on the other hand, refers to social or cultural distinctions associated with a given gender.

When babies are born, they are assigned a gender based on their biological sex—male babies are assigned as boys, female babies are assigned as girls, and intersex babies are born with sex characteristics that do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies, and are usually relegated into one gender category or another. Scholars generally regard gender as a social construct, meaning that it doesn’t exist naturally but is instead a concept that is created by cultural and societal norms. From birth, children are socialized to conform to certain gender roles based on their biological sex and the gender to which they are assigned.[1]

A person’s subjective experience of their own gender and how it develops, or gender identity, is a topic of much debate. It is the extent to which one identifies with a particular gender; it is a person’s individual sense and subjective experience of being a man, a woman, or other gender. It is often shaped early in life and consists primarily of the acceptance (or non-acceptance) of one’s membership into a gender category. In many societies, there is a basic division between gender attributes assigned to males and females. In all societies, however, some individuals do not identify with some (or all) of the aspects of gender that are assigned to their biological sex.

Those that identify with the gender that corresponds to the sex assigned to them at birth (for example, they are assigned female at birth and continue to identify as a girl, and later a woman) are called cisgender. In many Western cultures, individuals who identify with a gender that is different from their biological sex (for example, they are assigned female at birth but feel inwardly that they are a boy or a gender other than a girl) are called transgender. Some transgender individuals, if they have access to resources and medical care, choose to alter their bodies through medical interventions such as surgery and hormonal therapy so that their physical being is better aligned with their gender identity.

Recent terms such as “genderqueer,” “genderfluid,” “gender variant,” “androgynous,” “agender,” and “gender nonconforming” are used by individuals who do not identify within the gender binary as either a man or a woman. Instead they identify as existing somewhere along a spectrum or continuum of genders, or outside of the spectrum altogether, often in a way that is continuously evolving.

The Gender Continuum

Viewing gender as a continuum allows us to perceive the rich diversity of genders, from trans- and cisgender to gender queer and agender. Most Western societies operate on the idea that gender is a binary, that there are essentially only two genders (men and women) based on two sexes (male and female), and that everyone must fit one or the other. This social dichotomy enforces conformance to the ideals of masculinity and femininity in all aspects of gender and sex—gender identity, gender expression, and biological sex.

According to supporters of queer theory, gender identity is not a rigid or static identity but can continue to evolve and change over time. Queer theory developed in response to the perceived limitations of the way in which identities are thought to become consolidated or stabilized (for instance, gay or straight), and theorists constructed queerness in an attempt to resist this. In this way, the theory attempts to maintain a critique rather than define a specific identity. While “queer” defies a simple definition, the term is often used to convey an identity that is not rigidly developed but is instead fluid and changing.[2]

Video briefly defines different gender identities.

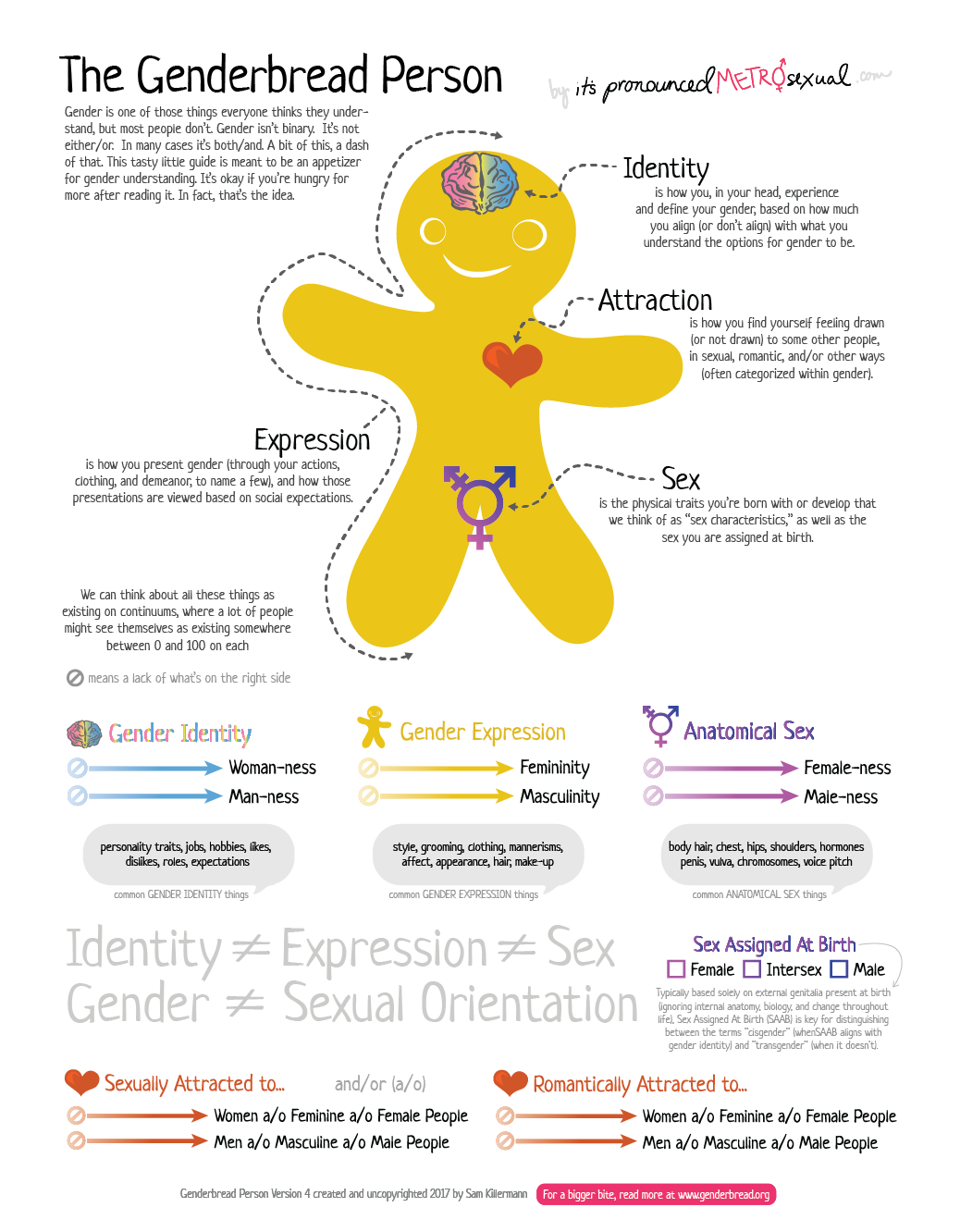

The Genderbread Person

In 2012, Sam Killerman created the Genderbread Person as an infographic to break down gender identity, gender expression, biological sex, and sexual orientation.[3] He has since updated it to version 4.0 to be more accurate, and inclusive.[4]

Video talks through aspects of one’s identity that are highlighted with the Gingerbread Person model.

Gender Pronouns

Pronouns are a part of language used to refer to someone or something without using proper nouns. In standard English, some singular third-person pronouns are “he” and “she,” which are usually seen as gender-specific pronouns, referring to a man and a woman, respectively. A gender-neutral pronoun or gender-inclusive pronoun is one that gives no implications about gender, and could be used for someone of any gender.

Some languages only have gender-neutral pronouns, whereas other languages have difficulty establishing any that aren’t gender-specific. People with non-binary gender identities often choose new third-person pronouns for themselves as part of their transition. They often choose gender-neutral pronouns so that others won’t see them as female or male.[5]

Here is a table based on the Rainbow Coalition of Yellowknife’s Handy Guide to Pronouns offering three examples of pronouns people may use:

|

Pronouns |

Example |

|

He/His/Him (masculine pronouns) |

He is going to the store to buy himself a hat. I saw him lose his old hat yesterday. |

|

She/Her/Her (feminine pronouns) |

She is going to the store to buy herself a hat. I saw her lose her old hat yesterday. |

|

They/Them/Their (gender neutral pronouns) |

They are going to the store to buy themselves a hat. I saw them lose their old hat yesterday. |

Factors that Influence Gender Identity

Although the formation of gender identity is not completely understood, many factors have been suggested as influencing its development. Biological factors that may influence gender identity include pre- and post-natal hormone levels and genetic makeup. Social factors include ideas regarding gender roles conveyed by family, authority figures, mass media, and other influential people in a child’s life. According to social-learning theory, children develop their gender identity through observing and imitating the gender-linked behaviors of others; they are then “rewarded” for imitating the behaviors of people of the same gender and “punished” for imitating the behaviors of another gender. For example, male children will often be rewarded for imitating their father’s love of baseball but punished or redirected in some way if they imitate their older sister’s love of dolls. Children are shaped and molded by the people surrounding them, who they try to imitate and follow.

Gender Roles

The term “gender role” refers to society’s concept of how people of a particular gender are expected to act. As we grow, we learn how to behave from those around us. In this socialization process, children are introduced to certain roles that are typically linked to their biological sex. Gender roles are based on norms, or standards, created by society. In American culture, masculine roles have traditionally been associated with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles have traditionally been associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination.

Gender Socialization

The socialization process in which children learn these gender roles begins at birth. Today, our society is quick to outfit male infants in blue and girls in pink, even applying these color-coded gender labels while a baby is in the womb. It is interesting to note that these color associations with gender have not always been what they are today. Up until the beginning of the 20th century, pink was actually more associated with boys, while blue was more associated with girls—illustrating how socially constructed these associations really are.

Gender socialization occurs through four major agents: family, education, peer groups, and mass media. Each agent reinforces gender roles by creating and maintaining normative expectations for gender-specific behavior. Exposure also occurs through secondary agents, such as religion and the workplace. Repeated exposure to these agents over time leads people to develop a sense that they are acting naturally based on their gender rather than following a socially constructed role.

Gender Stereotypes, Sexism, and Gender-Role Enforcement

The attitudes and expectations surrounding gender roles are not typically based on any inherent or natural gender differences, but on gender stereotypes, or oversimplified notions about the attitudes, traits, and behavior patterns of males and females. We engage in gender stereotyping when we do things like making the assumption that a teenage babysitter is female.

While it is somewhat acceptable for women to take on a narrow range of masculine characteristics without repercussions (such as dressing in traditionally male clothing), men are rarely able to take on more feminine characteristics (such as wearing skirts) without the risk of harassment or violence. This threat of punishment for stepping outside of gender norms is especially true for those who do not identify as male or female.

Gender stereotypes form the basis of sexism, or the prejudiced beliefs that value males over females. Common forms of sexism in modern society include gender-role expectations, such as expecting women to be the caretakers of the household. Sexism also includes people’s expectations of how members of a gender group should behave. For example, girls and women are expected to be friendly, passive, and nurturing; when she behaves in an unfriendly or assertive manner, she may be disliked or perceived as aggressive because she has violated a gender role (Rudman, 1998). In contrast, a boy or man behaving in a similarly unfriendly or assertive way might be perceived as strong or even gain respect in some circumstances.[7]

MEDIA: INFLUENCES ON TEENS

Media is another agent of socialization that influences our political views; our tastes in popular culture; our views of women, people of color, and the LGBTQ+ community; and many other beliefs and practices. In an ongoing controversy, the media is often blamed for youth violence and many other of society’s ills. The average child sees thousands of acts of violence on television and in the movies before reaching young adulthood. Musical lyrics may extol violence or aggression, including violence against women. Commercials can greatly influence our choice of soda, shoes, and countless other products. The mass media may also reinforce racial and gender stereotypes, including the belief that women are sex objects and suitable targets of male violence. In the General Social Survey (GSS), about 28% of respondents said that they watch four or more hours of television every day, while another 46% watch 2-3 hours daily (see “Average Number of Hours of Television Watched Daily”). The media certainly are an important source of socialization that was unimaginable a half-century ago.

As the media socializes children, adolescents, and even adults, a key question is the extent to which media violence causes violence in our society. Studies consistently uncover a strong correlation between watching violent television shows and movies and committing violence. However, this does not necessarily mean that watching the violence actually causes violent behavior: perhaps people watch violence because they are already interested in it and perhaps even committing it. Scholars continue to debate the effect of media violence on youth violence. In a free society, this question is especially important, as the belief in this effect has prompted calls for monitoring the media and the banning of certain acts of violence. Civil libertarians argue that such calls smack of censorship that violates the First Amendment to the Constitution, while others argue that they fall within the First Amendment and would make for a safer society. Certainly the concern and debate over mass media violence will continue for years to come.[1]

Queer is not specific to sexual identity or gender identity and can be used to refer to the community as a whole. While Queer was used as a derogatory term for decades, it was reclaimed by the LGBTQ community in the 1990s with the rise of an organization called Queer Nation. As an activist group out of New York, Queer Nation opposed discrimination of the LGBTQ community and rejected the heteronormative ideals of society.

What does the plus sign mean?

Recently LGBTQ is also used as LGBTQ+. The plus sign, “+” accounts for many additional identifications in the community, including two-spirit, intersex, asexual, pansexual, and gender queer. Gender Queer is an umbrella term that can be used for all gender identities not exclusive to masculine or feminine, including gender fluid, agender, bigender, pan gender, gender free, genderless, gender variant, and gender non-conforming. The plus also includes allies or people in support of the LGBTQ community.

While LGBTQ+ or Queer are currently the most common terms, the important takeaway is that the community will continue to evolve, and the terminology will evolve with it.[6]

Open identification of one’s sexual orientation or sexual identity may be hindered by homophobia, which encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward people who are identified or perceived as being LGBTQ. It can be expressed as antipathy, contempt, prejudice, aversion, or hatred; it may be based on irrational fear and is sometimes related to religious beliefs (Carroll, 2016). Homophobia is observable in critical and hostile behavior, such as discrimination and violence on the basis of sexual identities that are non- heterosexual. Recognized types of homophobia include institutionalized homophobia, such as religious and state-sponsored homophobia, and internalized homophobia in which people with same-gender attractions internalize, or believe, society’s negative views and/or hatred of themselves.

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual people regularly experience stigma, harassment, discrimination, and violence based on their sexual orientation (Carroll, 2016). Research has shown that gay, lesbian, and bisexual teenagers are at a higher risk of depression and suicide due to exclusion from social groups, rejection from peers and family, and negative media portrayals of LGBTQ individuals (Bauermeister et al., 2010). Discrimination can occur in the workplace, in housing, at schools, and in numerous public settings. Much of this discrimination is based on stereotypes and misinformation. Major policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have only come into effect in the United States in the last few years.[7]

Adolescent Sexuality

Human sexuality refers to people’s sexual interest in and attraction to others, as well as their capacity to have erotic experiences and responses. Sexuality may be experienced and expressed in a variety of ways, including thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles, and relationships. These may manifest themselves in biological, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual aspects. The biological and physical aspects of sexuality largely concern the human reproductive functions, including the human sexual-response cycle and the basic biological drive that exists in all species. Emotional aspects of sexuality include bonds between individuals that are expressed through profound feelings or physical manifestations of love, trust, and care. Social aspects deal with the effects of human society on one’s sexuality, while spirituality concerns an individual’s spiritual connection with others through sexuality. Sexuality also impacts, and is impacted by cultural, political, legal, philosophical, moral, ethical, and religious aspects of life.

The Human Sexual Response Cycle: Sexual motivation, often referred to as libido, is a person’s overall sexual drive or desire for sexual activity. This motivation is determined by biological, psychological, and social factors. In most mammalian species, sex hormones control the ability to engage in sexual behaviors. However, sex hormones do not directly regulate the ability to have sexual intercourse or to copulate in primates (including humans); rather, they are only one influence on the motivation to engage in sexual behaviors. Social factors, such as work and family also have an impact, as do internal psychological factors like personality and stress. Sex drive may also be affected by hormones, medical conditions, medications, lifestyle stress, pregnancy, and relationship issues.

The human sexual response cycle is a model that describes the physiological responses that take place during sexual activity. According to Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin (1948), the cycle consists of four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution.

|

Phase |

Description |

|

Excitement Phase |

the phase in which the intrinsic (inner) motivation to pursue sex arises |

|

Plateau Phase |

the period of sexual excitement with increased heart rate and circulation that sets the stage for orgasm |

|

Orgasm Phase |

the climax |

|

Resolution Phase |

the un-arousal state before the cycle begins again |

Societal Views on Sexuality: Society’s views on sexuality are influenced by everything from religion to philosophy, and they have changed throughout history and are continuously evolving. Historically, religion has been the greatest influence on sexual behavior in the United States; however, in more recent years, peers and the media have emerged as two of the strongest influences, particularly among American teens (Potard, Courtois, & Rusch, 2008).

Media Influences on Sexuality: Media in the form of television, magazines, movies, music, online, etc., continues to shape what is deemed appropriate or normal sexuality, targeting everything from body image to products meant to enhance sex appeal. Media serves to perpetuate a number of social scripts about sexual relationships and the sexual roles of men and women, many of which have been shown to have both empowering and problematic effects on people’s (especially women’s) developing sexual identities and sexual attitudes.

Cultural Differences with Sexuality: In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States and Canada, and in northern and Eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties, when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross- cultural comparisons, about three fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age 20, versus less than one fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield & Rapson, 2006).[8]

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0; Lifespan Development – Module 7: Adolescence by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0; Lifespan Development – Module 7: Adolescence by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Dating Abuse and Teen Violence (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/dating_abuse_and_teen_violence_ncadv.pdf ↵

- Who is Doing What to Whom? Determining the Core Aggressor in Relationships Where Domestic Violence Exists. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/who_is_doing_what_to_whom.pdf ↵

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). National Domestic Violence Awareness Month. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/resources/public-awareness/national-domestic-violence-awareness-month ↵

- Understanding the Acronyms: LGBT, LGBTQ, LGBTQ+. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.horizon- health.org/blog/2019/01/understanding-the-acronym-lgbtq/ ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 Boundless Psychology – Gender and Sexuality references Curation and Revision by Boundless Psychology, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (sections modified by Courtney Boise) ↵

- Sociology: Brief Edition – Agents of Socialization by Steven E. Barkan is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Intersex by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Boundless Psychology – Gender and Sexuality references Curation and Revision by Boundless Psychology, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- The Genderbread Person by Sam Killermann is in the public domain ↵

- The Genderbread Person v4.0 by Sam Killermann is in the public domain ↵

- Pronouns by Nonbinary Wiki is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Rainbow Coalition of Yellowknife. (n.d). Handy Guide to Pronouns [PDF files]. Retrieved from http://www.rainbowcoalitionyk.org/resources/.; ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (sections modified by Courtney Boise) ↵

- Introduction to Psychology by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond licensed under CC BY 4.0 (sections modified by Courtney Boise) ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Introduction to Psychology by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Education, Society, & the K-12 Learner – Part II: Educational Psychology references Modification of Erickson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development by Boundless, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0; ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Adolescent Development by Jennifer Lansford is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Developmental Psychology – Chapter 7: Adolescence by Laura Overstreet is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵