Visual Rhetoric

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Visual Rhetoric

These OWL resources will help you understand and work with rhetorical theories regarding visual and graphical displays of information. This area includes resources on analyzing and producing visual rhetoric, working with colors, and designing effective slide presentations.

Visual Rhetoric: Overview

What is visual rhetoric?

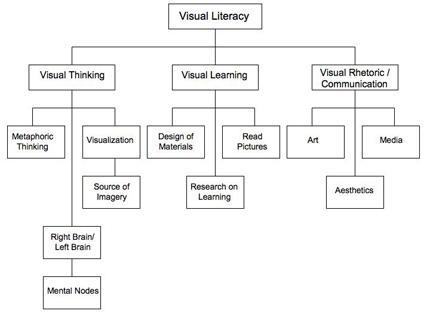

The term visual rhetoric falls under an umbrella term known as visual literacy, which is generally split into three categories: visual thinking, visual learning, visual rhetoric/communication (though clearly visual thinking and visual learning must occur in order to communicate visually). The following diagram illustrates these ideas. The graphic is modified from Sandra Moriarty’s diagram in her essay, “A Conceptual Map of Visual Communication” and from “Teaching Visual Literacy and Document Design in First-Year Composition” (MA Thesis) by Allen Brizee.

Visual Literacy

Essentially, a beginning definition of visual rhetoric and its applications are as follows:

- Use of images as argument

- Arrangement of elements on a page

- Use of typography (fonts, etc.)

- Analysis of existing images and visuals

Other OWL resources that are related to visual rhetoric and that may help you understand these ideas are the following:

- Visual Rhetoric Slide Presentation

- Color Theory Slide Presentation

- Using Fonts with Purpose

- Design an Effective PowerPoint Presentation

- HATS (Headings, Access, Typography, and Space) Slide Presentation: A Design Procedure for Routine Business Documents

For more information:

You may also download the pdf Works Cited and Works Referenced from “Teaching Visual Literacy and Document Design in First-Year Composition” in the Media box above. This pdf contains a number of resources on visual literacy, visual rhetoric, and document design and the uses of these concepts in composition and professional writing.

Visual Rhetoric: Text Elements

Lorem Ipsum Text Placeholder

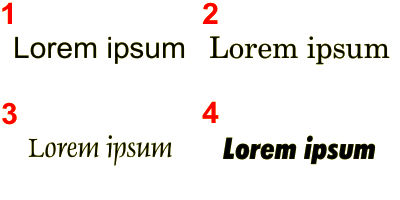

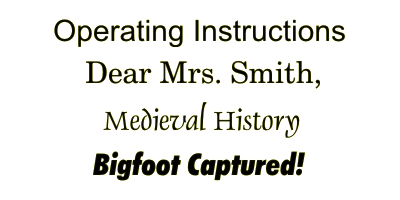

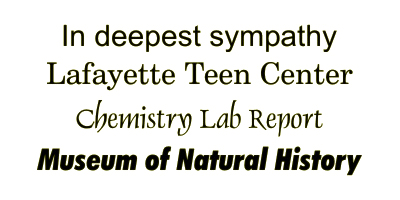

Even with just these four type faces, we can see different personalities (however limited), levels of formality, and even hints of the rhetorical concept ethos emerging (one’s credibility). Novice designers tend to choose fonts not according to their rhetorical situation, but rather to what they think looks pretty, or cool, or whatever. But it’s important to think about the kinds of visual/cultural associations that different fonts bring with them. Here are the same four fonts, with text that appears visually/culturally appropriate:

Arial, Century Schoolbook, Dauphin, Futura Xtra Black Condensed Italic

The first two fonts (Arial and Century Schoolbook, respectively) may not jump out at you as having a whole lot of cultural associations; that’s partly by design—the fonts are deliberately nondescript (especially Arial), and thus are used quite commonly. Not so with the fonts used for “Medieval History” (Dauphin) and “Bigfoot Captured!” (Futura Xtra Black Condensed Italic). The “Medieval History” text looks like our cultural conception of Medieval script. That is, the font looks almost like it was hand-written. Likewise, we’ve all seen tabloid papers in the checkout lanes of the supermarket, announcing in bold, loud text all sorts of incredible news.

Let’s look again at a negative example, where these cultural codes are ignored:

Arial, Century Schoolbook, Dauphin, Futura Xtra Black Condensed Italic Used Out of Context

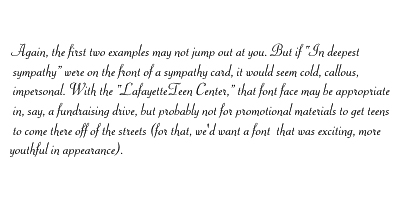

Again, the first two examples may not jump out at you. But if “In deepest sympathy” were on the front of a sympathy card, it would seem cold, callous, impersonal. With the “Lafayette Teen Center,” that font face may be appropriate in, say, a fundraising drive, but probably not for promotional materials to get teens to come there off of the streets (for that, we’d want a font that was exciting, more youthful in appearance). The “Chemistry Lab Report” example might seem OK at first glance (it’s formal, it evokes a sense of history with the word “chemistry”—though chemistry is a relatively young discipline), but it fails rhetorically because it does not acknowledge the expectations of the general audience of chemists or chemistry instructors. Taken in that light, in fact, the text for “Chemistry Lab Report” looks ridiculous. Likewise with “Museum of Natural History”; we still see the tabloid headline in it, as though “Overtaken by Mutants” were the words we’d expect next!

Headline versus Body Text

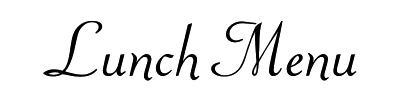

Keeping in mind the ideas we’ve already covered, there is an issue of readability involved in font choices. For example, this script font is fine for the following headline text:

Lunch Menu

However, let’s repeat the text from the preceding section in the same font:

Script block text

Now, that font may be OK if that’s all the text there is. But can you imagine reading that for five pages? 25? An entire biology textbook? Absolutely not! This is specifically why we have fonts like Times New Roman or Arial (though there are far better choices, in print, than those): they are comfortable to read for quite awhile; we don’t have to strain to read the words.

Text and the Web

When novice designers bring some of their bad font-choice habits to the Web, the results can be disastrous.

First, there is the issue of how fonts get handled on the Web. You may have a computer with hundreds or even thousands of fonts installed on it, and as you’re designing for the Web on that computer, it may seem no big deal to use Poster Wangedoodle Medium Xtra Bold, or whatever font it is that you’re feeling is appropriate. However, you must realize that not all users have that (and many other fonts) installed on their computers. So stick with the simple standard for HTML text: Arial, Verdana, etc. In certain Web-authoring programs, you can also specify simply San Serif (no ornamentation, like Arial) or Serif (ornamentation, like Times New Roman); in these cases, your Web audience’s browser will use a common font on the user’s machine.

Second, following directly from the first issue, is screen readability. Some fonts that look awesome in print fail miserably on the screen (and vice-versa; Times New Roman is a great screen font, but doesn’t work as well when it’s printed). Again, even assuming the compatibility issues we just covered, fonts meant to look like handwritten script become practically illegible. And if the font used on a Web page isn’t on the user’s computer, they may just get a string of boxes or nonsense characters.

TEXT SUMMARY:

Questions to Consider When Choosing Fonts

- What kinds of expectations does my audience have regarding fonts? Are they scholars or soccer fans? Church-goers or movie-goers?

- What am I representing in my font choices? Am I a job applicant? A student writing a seminar paper? A club officer making a poster to advertise a formal dinner?

- What kind of text am I running in different fonts? Headlines or fine print? Body text or bulleted lists?

- What distance is my text being viewed at? On a greeting card or a bumper sticker? A poster or a flyer?

- What fonts are commonly available on computers that I can use for the Web? What kinds of alternatives are available for text that cannot be displayed in Web browsers?

Visual Rhetoric: Color

Many beginning designers, however, find themselves overwhelmed by the palettes available on most comptuers, and begin choosing colors for the palette of their designed based on favorites. However, results like that can be disastrous:

Blue on Red

Can you read that? Not comfortably! Imagine an entire screen of text like that. Part of the reason that this color combination (which appears more frequently on the Web than you can imagine) is so hard on the eyes has to do with how computer screens handle color information. If you move your face close enough to the screen, you’ll notice an almost black outline at the left side of the characters, and a strange, almost white glow at the right. Why? Computer screens are made up of tiny little boxes of light, called pixels. Each pixel contains a red element, a green element, and a blue element (you can see this even better on a standard television set). But what happens in this case is the red element of the red areas of the screen is full on (leaving green and blue dark), and the blue element of the blue areas is full on (leaving red and green dark). The result is a literal “black hole” on the left side (remember, RED GREEN BLUE), and a glow on the right (since both the far-right BLUE element is full on, as is the far-left RED).

OK, enough technical information. But another problem with this palette is the fact that blue and red do not have much contrast from one another—they are roughly the same brightness. Worse than that, red is culturally-coded to jar us (just like the bulls at the Plaza de Toros). That’s why red is typically used on everything from stop signs and stop lights to warning labels and fire alarms.

![]()

Gray on Yellow

Now, this is not an ideal palette—but it does illustrate our concern with contrast. This may not be a fun palette for reading several thousand pages of an online novel, but it’s great for small areas of text and encouraging a soft, peaceful mood.

![]()

Black on Yellow

Part of what’s at issue with these colors—the black versus the grays, the muted versus bright yellows—is the idea of saturation. Saturation is how much of a color there is. You might think back to when you painted with watercolors as a child. If you really scrubbed your brush around in the yellow paint, you’d get a deep, bright yellow. But by watering the brush down, and dabbing just the tiniest bit of yellow, you got something of a more faint, muted yellow.

One of the common mistakes that beginning designers make is using highly-saturated colors (which is another reason the red-on-blue thing didn’t work above). Perhaps it’s because we liked the brightest-colored crayons as children. However, you’ll find that most sophisticated designs tend to use muted/desaturated colors.

Finally, the advice we’ll leave you with (besides “go pick up a few dozen books on color theory”) is this: just like we have certain culturally-loaded sensibilities when it comes to font choices, the same is often true for color. Think, for example, about the difference in color schemes between a Best Buy ad (deep blues, bright yellows) and a Fall catalogue for J. Crew (deep wood-tones, crisp blue-grays). Each one conveys a level of excitement (or not), and a degree of sophistication. Observe the colors around you—see what they do, and what impacts they have on you. Bring those ideas with you as you design with color. And remember: it’s no sin to borrow and experiment with a color scheme you find.

Color Summary: Questions to Consider

When Choosing Colors

- Does the combination of colors you’re using lend itself to easy reading, either on-screen or on paper?

- Are the cultural associations, if any, accompanying the colors appropriate?

Visual Rhetoric: Use of Images

A. Clip-Art

Very little commercially-available clip-art looks good or has any type of sophistication—especially clip art that comes packaged with common software programs. Clip-art is often cartoony and silly, or abstract and general to the point of being useless. And remember: every user of Microsoft Word has the same clipart, and has probably used it, and will recognize it when you use it, and be unimpressed accordingly.

When choosing visuals, think about the kinds of extra information that is conveyed. For example, this piece of clipart seems to be a nice touch for advertising a pipe and cigar shop:

Clipart

But then there are so many elements that surround the main object of emphasis, which in this case is the pipe. Besides, again, the “cartoony” look, there are ridiculous, outmoded fashions (which may be OK if the design is striving for an antique/nostalgic look), plus there is an issue of colors that get introduced by the clipart (if your design scheme is using deep reds and yellows, say, this is going to look awful). And what’s with the guy’s facial expression? Yet most beginning designers will look no further than the pipe, and ruin their design because of it. Worse still, for this rhetorical situation (but certainly not for public health), there is the depiction of the health-hazardous act of smoking.

If the pipe is what’s important, then perhaps seek out something along these lines:

Pipe Clipart

Again, there is a palette at work here (although it’s natural to what we think of as pipe); but more importantly, there is a style: the rough lines, for example. While it’s not cartoony, this pipe may not fit into a total design (see the Overall Design section below).

Why is clipart so difficult to work with? Because clipart is often stylized and colored, it may be hard to find some that really works well with your design, and manages to pull off the kind of ethos you’re striving for.

B. Illustrations and Diagrams

Like clipart, illustrations and diagrams can make or break a design. However, unlike clipart, which is meant usually as an accent, illustrations and diagrams often serve a central purpose to inform.

Always strive for clarity in illustrations and diagrams. Think about maps, for example. A driving atlas of the United States does not include representations and labels of every single office building, townhouse, apartment, gas station, and tool shed between New York City and Los Angeles. If it did, we’d have a hard time reading what we really want out of the map: the roads! Illustrations and diagrams are selective pictures of reality; that’s what makes them useful. In the case of representing large amounts of complex information, it is probably helpful to break up the information spatially—that’s why driving atlases of the United States are in book form, and not gigantic maps; each state gets its own page, rather than the entire country squeezed onto a bedsheet-sized piece of paper.

C. Graphs

Programs like Microsoft Excel will automatically generate everything from bar graphs to pie charts; you can choose things like color and scale. Some issues to consider when choosing to graphically represent quantitative information:

- Everyone likes pie charts, but they are only helpful in terms of showing parts of a whole. So if your figures are not in percentages, pie charts won’t be of much help to you. And unless several pie charts are included, they are not useful for demonstrating changes over time.

- Bar graphs are especially helpful for comparisons between a number of different numeric variables, even over time.

- Line graphs are excellent for plotting changes in one variable over time, particularly over small time segments. When multiple colors are used, several variables can be plotted, but too many lines may be confusing, and a bar graph might be a better choice.

D. Photographs and Manipulated Images

With the availability of digital cameras, scanners, and other imaging devices coupled with the easy electronic distribution of photo-quality images, photographs are more popular than ever. Yet many beginning designers tend to avoid capturing their own images. Many will search the Web for images and, quality or not, copyright or not, will select the first available image. Again, we stumble onto the important question of ethos, which in the world of photographic images is primarily tied to two aspects of the photographic image: composition and quality.

We’ll start with the second aspect, quality. Practically every computer image format has some settings for “compressing” the image. That is, areas of similar color lose their information, and are filled in with approximations when the image is opened in a Web browser or other program. Especially when designing for a Web audience, there is a constant push and pull between the quality of the image, and its size on disk. The better quality image, the larger it is on disk, and thus the longer it takes to load in a Web browser. However, in terms of ethos—and this itself is audience-dependent—it is often wise to opt for a slightly larger image file, rather than sacrifice quality.

Consider these two photos of the Purdue Memorial Union:

Good Picture

Poor Picture

In both photos, the subject matter is clear; however, the quality is strikingly different. While the first photo still uses a fairly high compression, little details like the wisps of clouds and treetops are clear, as is the texture of the bricks and the panes in the windows. The second photo is clearly degraded—there are large blocks of blue visible in the sky area, and there are “sparkles” between the treetops and clouds, and the building and sky. Of course, the top photo file is three times larger than the bottom—but is the speed with which the second photo can be transferred worth the loss in quality? If this photo were in the context of a Web page meant to encourage students to come study at Purdue, which would likely have a more powerful effect on your impression of the University? Why?

In terms of composition, remember that photos are basically frames of reality. Any given subject can be photographed an infinite number of ways, both in terms of the framing (what is where in the shot) and the exposure (shutter speed, aperture, etc.) When shooting or selecting your images, pay careful attention to how the shot is composed. Is the image light? Dark? What gets highlighted? What is the central subject in the shot? What do you notice? Is there anything inappropriate in the shot that you wouldn’t want? Now, there are entire books and courses on photography, so we’ll have to limit our discussion to what has been said so far, with the exception of that last question: Is there anything inappropriate in the shot that you wouldn’t want? Digital photo manipulation has opened up huge possibilities for image manipulation. Consider the following two images:

Original Picture

Manipulated Picture

In the top image, various clutter (in this case, street lights) have been removed to improve the overall look of the Lafayette skyline. The question is this: what is the line between an accurate portrayal of reality, and an aesthetic representation of it? How is our ethos as visually-oriented writers affected, positively and negatively, when we manipulate images to achieve a certain effect?