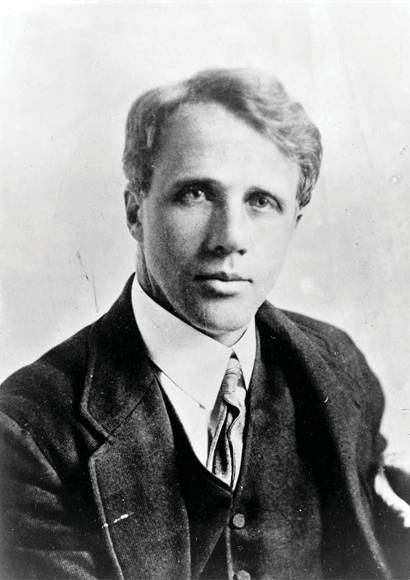

Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Image 5.1 | Robert Frost, circa 1910

Photographer | Unknown

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

When Robert Frost was asked to recite “The Gift Outright” at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy in 1961, he was not only the first poet to be invited to participate in a presidential inauguration, he was also an American icon whose poetry was as recognizable to the nation as were Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers. Yet like his contemporary Rockwell, Frost’s poems reflect a rapidly changing cultural landscape in which the warm glow of memory was tinted by the cold reality of a highly mechanized, and often cruel, world. Frost was no passive megaphone for a comfortable past; like other Modernists, Frost melded traditional forms to the American vernacular to produce poetry that was strikingly American and contemporary.

Listeners and readers who are unfamiliar with Frost’s poetry often remark on the consistency of his poetic voice. Many of the poems, in fact, appear to originate from the same person, an older New England gentleman who spends much of his time reminiscing about the past, remarking wistfully on the changes taking place around him, and celebrating those rare moments when he has stepped out of the norm. Thus, poems like “The Road Not Taken,” are often recited at high school graduation ceremonies as a way to encourage students to take risks and celebrate life. Closer inspection of the poems reveals that this voice is not Frost’s at all, but that of an alter ego who exists not to highlight the past glories, but to underline very contemporary frustrations with a decaying world.

“Mending Wall,” a poem written around the time of Frost’s fortieth birthday in 1914, is a strong introduction to his use of this alter ego. A dramatic monologue in forty-five lines of iambic pentameter, the poem opens with the vague pronouncement, “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,” and proceeds to spell out the conditions for this seasonal activity, that of mending the fence that separates two farms. As the speaker and his neighbor proceed to rebuild the wall, each one responsible for the stones that have fallen onto his own side, the first farmer pauses to reflect on how it is that every year the wall requires new attention even though no one, save for a few hunters, has been observed disturbing the stones. This annual cycle of decay and reconstruction is at the heart of this poem, and the need for annual maintenance occurs not only in the world of fences, but in the world of human relationships as well.

This idea of continual decay and maintenance in human relationships provides a useful frame for understanding “Home Burial,” a longer narrative poem that describes the apparently divergent responses of a husband and wife to the death of one of their children. A primer in the relationship between appearance and reality as the wife and husband struggle to understand their individual responses to this most recent death, the poem continues the theme of decay and rebuilding that is apparent in “Mending Wall.” As the husband and wife appear to move closer together in the poem, they must also rebuild trust in their own relationship. Throughout Frost’s poetry this cycle of decay and reconstruction continues unabated.

“Mending Wall”

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbour know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

“Stay where you are until our backs are turned!”

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, “Good fences make good neighbours.”

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

“Why do they make good neighbours? Isn’t it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offence.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.” I could say “Elves” to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, “Good fences make good neighbours.”

“Home Burial”

He saw her from the bottom of the stairs

Before she saw him. She was starting down,

Looking back over her shoulder at some fear.

She took a doubtful step and then undid it

To raise herself and look again. He spoke

Advancing toward her: “What is it you see

From up there always—for I want to know.”

She turned and sank upon her skirts at that,

And her face changed from terrified to dull.

He said to gain time: “What is it you see,”

Mounting until she cowered under him.

“I will find out now—you must tell me, dear.”

She, in her place, refused him any help

With the least stiffening of her neck and silence.

She let him look, sure that he wouldn’t see,

Blind creature; and awhile he didn’t see.

But at last he murmured, “Oh,” and again, “Oh.”

“What is it—what?” she said.

“Just that I see.”

“You don’t,” she challenged. ‘tell me what it is.”

‘the wonder is I didn’t see at once.

I never noticed it from here before.

I must be wonted to it—that’s the reason.

The little graveyard where my people are!

So small the window frames the whole of it.

Not so much larger than a bedroom, is it?

There are three stones of slate and one of marble,

Broad-shouldered little slabs there in the sunlight

On the sidehill. We haven’t to mind those.

But I understand: it is not the stones,

But the child’s mound—”

“don’t, don’t, don’t, don’t,” she cried.

She withdrew shrinking from beneath his arm

That rested on the banister, and slid downstairs;

And turned on him with such a daunting look,

He said twice over before he knew himself:

“Can’t a man speak of his own child he’s lost?”

“Not you! Oh, where’s my hat? Oh, I don’t need it!

I must get out of here. I must get air.

I don’t know rightly whether any man can.”

“Amy! Don’t go to someone else this time.

Listen to me. I won’t come down the stairs.”

He sat and fixed his chin between his fists.

‘there’s something I should like to ask you, dear.”

“You don’t know how to ask it.”

“Help me, then.”

Her fingers moved the latch for all reply.

“My words are nearly always an offense.

I don’t know how to speak of anything

So as to please you. But I might be taught

I should suppose. I can’t say I see how.

A man must partly give up being a man

With women-folk. We could have some arrangement

By which I’d bind myself to keep hands off

Anything special you’re a-mind to name.

Though I don’t like such things ‘twixt those that love.

Two that don’t love can’t live together without them.

But two that do can’t live together with them.”

She moved the latch a little. ‘don’t—don’t go.

Don’t carry it to someone else this time.

Tell me about it if it’s something human.

Let me into your grief. I’m not so much

Unlike other folks as your standing there

Apart would make me out. Give me my chance.

I do think, though, you overdo it a little.

What was it brought you up to think it the thing

To take your mother-loss of a first child

So inconsolably—in the face of love.

You’d think his memory might be satisfied—”

“there you go sneering now!”

“I’m not, I’m not!

You make me angry. I’ll come down to you.

God, what a woman! And it’s come to this,

A man can’t speak of his own child that’s dead.”

“You can’t because you don’t know how to speak.

If you had any feelings, you that dug

With your own hand—how could you?—his little grave;

I saw you from that very window there,

Making the gravel leap and leap in air,

Leap up, like that, like that, and land so lightly

And roll back down the mound beside the hole.

I thought, Who is that man? I didn’t know you.

And I crept down the stairs and up the stairs

To look again, and still your spade kept lifting.

Then you came in. I heard your rumbling voice

Out in the kitchen, and I don’t know why,

But I went near to see with my own eyes.

You could sit there with the stains on your shoes

Of the fresh earth from your own baby’s grave

And talk about your everyday concerns.

You had stood the spade up against the wall

Outside there in the entry, for I saw it.”

“I shall laugh the worst laugh I ever laughed.

I’m cursed. God, if I don’t believe I’m cursed.”

“I can repeat the very words you were saying:

‘three foggy mornings and one rainy day

Will rot the best birch fence a man can build.’

Think of it, talk like that at such a time!

What had how long it takes a birch to rot

To do with what was in the darkened parlor?

You couldn’t care! The nearest friends can go

With anyone to death, comes so far short

They might as well not try to go at all.

No, from the time when one is sick to death,

One is alone, and he dies more alone.

Friends make pretense of following to the grave,

But before one is in it, their minds are turned

And making the best of their way back to life

And living people, and things they understand.

But the world’s evil. I won’t have grief so

If I can change it. Oh, I won’t, I won’t!”

“there, you have said it all and you feel better.

You won’t go now. You’re crying. Close the door.

The heart’s gone out of it: why keep it up.

Amy! There’s someone coming down the road!”

“You—oh, you think the talk is all. I must go—

Somewhere out of this house. How can I make you—”

“If—you—do!” She was opening the door wider.

“Where do you mean to go? First tell me that.

I’ll follow and bring you back by force. I will!—”

Reading and Review Questions

- Compare and contrast the speakers in “Mending Wall” and “Home Burial.” How does each of these men understand the world around them?

- The two figures in “Mending Wall” rebuild the wall in silence. What does their silence tell us about their relationship?

- At the end of “Home Burial,” Amy appears ready to exit the house? Does she depart?

- Compare Frost’s “Home Burial” to Williams’s “The Dead Baby.”