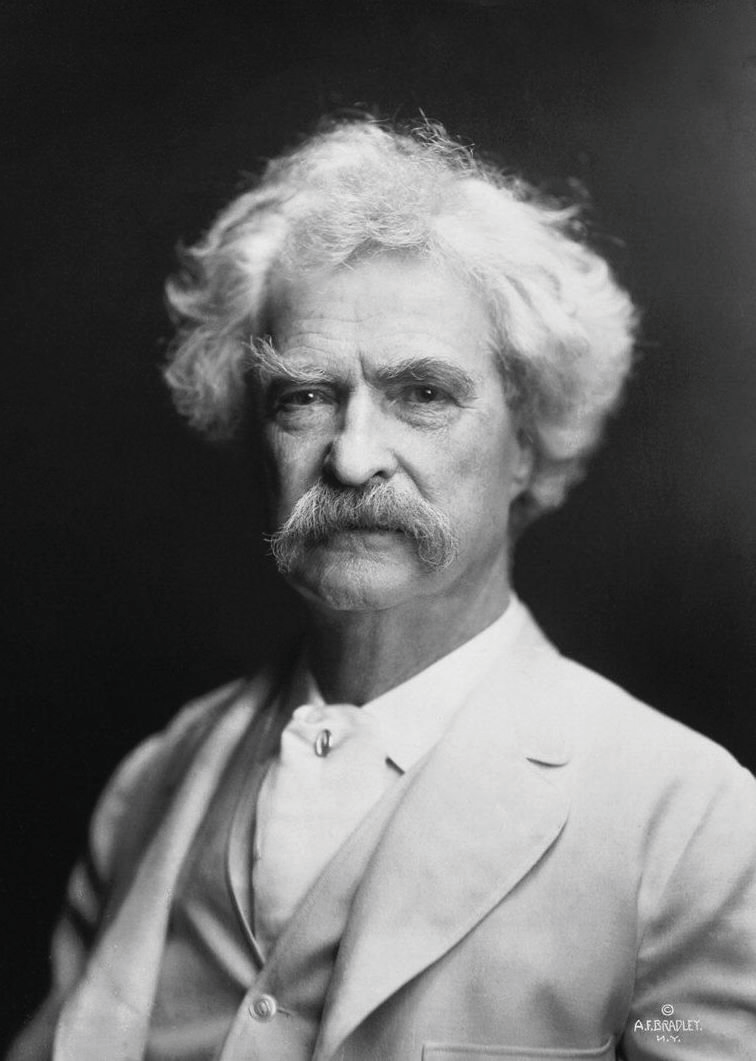

Mark Twain (1835-1910)

Mark Twain, 1907

Photographer | A. F. Bradley

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

Mark Twain is the pen name of author Samuel Langhorne Clemmons. Twain was born in Florida, Missouri, but grew up in Hannibal, Missouri, near the banks of the Mississippi River. This location was a major influence on his work and severed as the setting for many of his stories. Although Twain originally apprenticed as a printer, he spent eighteen months on the Mississippi River training as a riverboat pilot (the name Mark Twain is a reference to a nautical term). By the start of the Civil War (1861), traffic on the Mississippi River had slowed considerably, which led Twain to abandon his dreams of piloting a riverboat. Twain claims to have spent two weeks in the Marion Rangers, a poorly organized local confederate militia, after leaving his job on a riverboat. In 1861, Twain’s brother Orion was appointed by President Lincoln to serve as the Secretary of Nevada, and Twain initially accompanied him out West, serving as the Assistant Secretary of Nevada. Twain’s adventures out West would become the material for his successful book, Roughing It!, published in 1872, following on the heels of the success of his international travelogue, Innocents Abroad (1869). While living out West, Twain made a name for himself as a journalist, eventually serving as the editor of the Virginia City Daily Territorial Enterprise. The multi-talented Twain rose to prominence as a writer, journalist, humorist, memoirist, novelist, and public speaker.

Twain was one of the most influential and important figures of American Literary Realism, achieving fame during his lifetime. Twain was hailed as America’s most famous writer, and is the author of several classic books such as The Adventure of Tom Sawyer (1876), The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), Roughing It!, Innocents Abroad, Life on the Mississippi (1883), and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889). Twain is known for his use of dialect, regional humor, and satire, as well as the repeated theme of having jokes at the expense of an outsider (or work featuring an outsider who comes to fleece locals).

In his famous “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” which has also been published under its original title “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog” and “The Notorious Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” Twain experiments with early versions of meta-fiction, embedding a story within a story. Furthermore, the story relies on local color humor and regional dialect (“Why blame my cats”) as well as featuring an outsider entering a new place, a staple in Twain’s work. In Roughing It!, which details Twain’s travels out West from 1861-1867, Twain details many adventures visiting with outlaws and other strange characters, as well as encounters with notable figures of the age, such as Brigham Young and Horace Greeley. Furthermore, Roughing It! provided descriptions of the frontier from Nevada to San Francisco to Hawaii to an audience largely unfamiliar with the area. Although he claimed it to be a work of non-fiction, Roughing It! features many fantastic stories of Twain’s travels in the West, several of which were exaggerated or untrue. In “The War Prayer,” a satire of the Spanish-American War (1898), Twain proves to be a master of irony. The story, which was originally rejected during Twain’s lifetime, begins as a prayer for American soldiers and, as it continues, highlights many of the horrors of war.

“The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County”

In compliance with the request of a friend of mine, who wrote me from the East, I called on good-natured, garrulous old Simon Wheeler, and inquired after my friend’s friend, Leonidas W. Smiley, as requested to do, and I hereunto append the result. I have a lurking suspicion that Leonidas W. Smiley is a myth; that my friend never knew such a personage; and that he only conjectured that if I asked old Wheeler about him, it would remind him of his infamous Jim Smiley, and he would go to work and bore me to death with some exasperating reminiscence of him as long and as tedious as it should be useless to me. If that was the design it succeeded.

I found Simon Wheeler dozing comfortably by the bar-room stove of the dilapidated tavern in the decayed mining camp of Engel’s, and noticed that he was fat and bald-headed, and had an expression of winning gentleness and simplicity upon his tranquil countenance. He roused up and gave me good-day. I told him a friend of mine had commissioned me to make some inquires about a cherished companion of his boyhood named Leonidas W. Smiley—Rev. Leonidas W. Smiley, a young minister of the Gospel, who be had heard was at one time a resident of Angel’s Camp. I added that if Mr. Wheeler could tell me anything about this Rev. Leonidas W. Smiley, I would feel under many obligations to him.

Simon Wheeler backed me into a corner and blockaded me there with his chair, and then sat down and reeled off the monotonous narrative which follows this paragraph. He never smiled, he never frowned, he never changed his voice from the gentle-flowing key to which he tuned his initial sentence, be never betrayed the slightest suspicion of enthusiasm; but all through the interminable narrative there ran a vein of impressive earnestness and sincerity, which showed me plainly, that, so far from his imagining that there was anything ridiculous or funny about his story, he regarded it as a really important matter, and admired its two heroes as men of transcendant genius in finesse. I let him go on in his own way, and never interrupted him once.

“Rev. Leonidas W. H’m, Reverend Le—well, there was a feller here once by the name of Jim Smiley, in the winter of ‘49or maybe it was the spring of ‘5o—I don’t recollect exactly, somehow, though what makes me think it was one or the other is because remember the big flume warn’t finished when he first come to the camp; but any way he was the curiosest man about always betting on anything that turned up you ever see, if he could get anybody to bet on the other side; and if he couldn’t he’d change sides. Any way that suited the other man would suit him—any way just so’s he got a bet, he was satisfied. But still he was lucky, uncommon lucky; he most always come out winner. He was always ready and laying for a chance; there couldn’t be no solit’ry thing mentioned but that feller’d offer to bet on it, and take any side you please as I was just telling you. If there was a horse-race, you’d find him flush or you’d find him busted at the end of it; if there was a dog-fight, he’d bet on it; if there was a cat-fight he’d bet on it; if there was a chicken-fight he’d bet on it; why, if there was two birds sitting on a fence, he would bet you which one would fly first; or if there was a camp-meeting, he would be there reg’lar to bet on Parson Walker, which ·he judged to be the best exhorter about here, and so he was too, and a good man. If he even see a straddle-bug start to go anywheres, he would bet you how long it would take him to get to—to wherever he was going to, and if you took him up he would foller that straddle-bug to Mexico but what he would find out where he was bound for and how long he was on the road. Lots of the boys here has seen that Smiley, and can tell you about him. Why, it never made no difference to him—he’d bet on any thing—the dangdest feller. Parson Walker’s wife laid very sick once, for a good while, and it seemed as if they warn’t going to save her; but one morning he come in, and Smiley up and asked him how she was, and he said she was considerable better—thank the Lord for his inf’nit mercy—and coming on so smart that with the blessing of Prov’dence she’d get well yet; and Smiley, before he thought, says, “Well, I’ll resk two-and-a-half she don’t anyway.’’

Thish-yer Smiley had a mare—the boys called her· the fifteen minute nag, but that was only in fun, you know, because of course she was faster than that—and he used to win money on that horse, for all she was so slow and always had the asthma, or the distemper, or the consumption, or something of that kind. They used to give her two or three hundred yards’ start, and then pass her under way; but always at the fag end of the race she’d get excited and desperate-like, and come cavorting and straddling up and scattering her legs around limber, sometimes in the air, and sometimes out to one side amongst the fences, and kicking up m-o-r-e dust and raising m-o-r-e racket with her coughing and sneezing and blowing her nose—and always fetch up at the stand just about a neck ahead, as near as you could cipher it down.

And he had a little small bull-pup that to look at him you’d think he warn’t worth a cent but to set around and look ornery and lay for a chance to steal something. But as soon as money was up on him he was a different dog; his under jaw began to stick out like the fo’castle of a steamboat, and his teeth would uncover and shine like the furnaces. And a dog might tackle him and bullyrag him, and bite him, and throw him over his shoulder two or three times, and Andrew Jackson—which was the name of the pup—Andrew Jackson would never let on but what he was satisfied, and hadn’t expected nothing else—and the bets being doubled and doubled on the other side all the time, till the money was all up; and then all of a sudden he would grab that other dog jest by the j’int of his hind leg and freeze to it—not chaw, you understand, but only just grip and hang on till they throwed up the sponge, if it was a year. Smiley always come out winner on that pup, till he harnessed a dog once that did’nt have no hind legs, because they’d been sawed off in a circular saw, and when the thing had gone along far enough, and the money was all up, and he come to make a snatch for his pet holt, he see in a minute how he’d been imposed on, and how the other dog had him in the door, so to speak, and he ‘peared surprised, and then he looked sorter discouraged-like, and didn’t try no more to win the fight, and so he got shucked out bad. He give Smiley a look, as much as to say his heart was broke, and it was his fault, for putting up a dog that hadn’t no hind legs for him to take holt of, which was his main dependence in a fight, and then he limped off a piece and laid down and died. It was a good pup was that Andrew Jackson, and would have made a name for hisself if he’d lived, for the stuff was in him and he had genius—I know it, because he hadn’t no opportunities to speak of, and it don’t stand to reason that a dog could make such a fight as he could under them circumstances if he hadn’t no talent. It always makes me feel sorry when I think of that last fight of his’n, and the way it turned out.

Well, thish-yer Smiley had rat-tarriers, and chicken cocks, and tom-cats and all them kind of things, till you couldn’t rest, and you couldn’t fetch nothing f or him to bet on but he’d match you. He ketched a frog one day, and took him home, and said be cal’lated to educate him; and so he never done nothing for three months but set in his back yard and learn that frog to jump. And you bet you he did learn him, too. He’d give him a little punch behind, and the next minute you’d see that frog whirling in the air like a doughnut-see him turn one summerset, or maybe a couple, if he got a good start, and come down flat-footed and all right, like a cat. He got him up so in the matter of catching flies, and kep’ him in practice so constant, that he’d nail a fly every time as fur as he could see him. Smiley said all a frog wanted was education and he could do ‘most anything—and I believe him. Why, I’ve seen him set Dan’l Webster down here on this floor—Dan’l Webster was the name of the frog—and sing out, “Flies Dan’l, flies!” and quicker’n you could wink he’d spring straight up and snake a fly off’n the counter there, and flop down on the floor ag’in as solid as a gob of mud, and fall to scratching the side of his head with his hind foot as indifferent as if he hadn’t no idea he’d been doin’ any more’n any frog might do. You never see a frog so modest and straightfor’ard as he was, for all he was so gifted. And when it come to fair and square jumping on a dead level, he could get over more ground at one straddle than any animal of his breed you ever see. Jumping on a dead level was his strong suit, you understand; and when it come to that, Smiley would ante up money on him as long as he had a red. Smiley was monstrous proud of his frog, and well he might be, for fellers that had travelled and been everywhere, all said he laid over any frog that ever they see.

Well, Smiley kep’ the beast in a little lattice box, and he used to fetch him down town sometimes and lay for a bet. One day, a feller—a stranger in the camp, he was—come acrost him with his box, and says:

“What might it be that you’ve got in the box?”

And Smiley says, sorter indifferent-like, “It might be a parrot, or it might be a canary, maybe, but it ain’t—it’s only just a frog.”

And the feller took it, and looked at it careful, and turned it round this way and that, and says, “H’m—so ‘tis. Well, what’s he good for?”

“Well,” Smiley, says, easy and careless, “he’s good enough for one thing, I should judge—he can outjump any frog in Calaveras county.”

The feller took the box again, and took another long, particular look, and gave it back to Smiley, and says, very deliberate, “Well,’’ he says, “I don’t see no p’ints about that frog that’s any better’n any other frog.”

“Maybe you don’t,” Smiley says. “Maybe you understand frogs and maybe you don’t understand ‘em; maybe you’ve had experience, and maybe you ain’t only a amature, as it were. Anyways, I’ve got my opinion and I’ll resk forty dollars that he can outjump any frog in Calaveras county.”

And the feller studied a minute, and then says, kinder sad like, ‘‘Well, I’m only a stranger here, and I aint got no frog; but if I had a frog, I’d bet you.”

And then Smiley says, “That’s all right—that’s all right—if you’ll hold my box a minute, I’ll go and get you a frog.’’ And so the feller took the box, and put up his forty dollars along with Smiley’s, and set down to wait. So he sat there a good while thinking and thinking to hisself, and then he got the frog out and prized his mouth open and took a teaspoon and filled him full of quail shot—filled him pretty near up to his chin—and set him on the floor. Smiley he went to the swamp and slopped around in the mud for along time, and finally he ketched a frog, and fetched him in, and gave him to this feller and says:

“Now, if you’re ready, set him alongside of Dan’l, with his fore-paws just even with Dan’l’s, and I’ll give the word.” Then he says, “One—two—three—git !” and him and the feller touched up the frogs from behind, and the new frog hopped off lively, but Dan’l gave a heave, and hysted up his shoulders—so—like a Frenchman, but it warn’t no use—he couldn’t budge; he was planted as solid as a church, and he couldn’t no more stir than if he was anchored out. Smiley was a good deal surprised, and he was disgusted too, but he didn’t have no idea what the matter was, of course.

The feller took the money and started away; and when he was going out at the door, he sorter jerked his thumb over his shoulder—so—at Dan’l, and says again, very deliberate, “Well,” he says, “I don’t see no p’ints about that frog that’s any better’n any other frog.”

Smiley he stood scratching his head and looking down at Dan’l a long time, and at last he says, “I do wonder what in the nation that frog throw’d off for—I wonder if there ain’t something the matter with him—he ‘pears to look mighty _baggy, somehow.” And he ketched Dan’l by the nap of the neck, and hefted him, and says, “Why, blame my cats if he don’t weigh five pound!” and turned him upside down and he belched out a double handful of shot. And then he see how it was, and he was the maddest man—he set the frog down and took out after that feller, but he never ketched him. And—”

[Here Simon Wheeler heard his name called from the front yard, and got up to see what was wanted.] And turning to me as he moved away, he said: “Just set where yon are, stranger, and rest easy—I ain’t going to be gone a second.”

But, by your leave, I did not think that a continuation of the history of the enterprising vagabond Jim Smiley would be likely to afford me much information concerning the Rev. Leonidas W. Smiley, and so I started away.

At the door I met the sociable Wheeler returning, and he button-holed me and re-commenced:

“Well, thish-yer Smiley had a yaller one-eyed cow that didn’t have no tail, only jest a short stump like a bannanner, and—“

However, lacking both time and inclination, I did not wait to hear about the afflicted cow, but took my leave.

Selections from Roughing It

CHAPTER VII

IT did seem strange enough to see a town again after what appeared to us such a long acquaintance with deep, still, almost lifeless and houseless solitude! We tumbled out into the busy street feeling like meteoric people crumbled off the corner of some other world, and wakened up suddenly in this. For an hour we took as much interest in Overland City as if we had never seen a town before. The reason we had an hour to spare was because we had to change our stage (for a less sumptuous affair, called a “mud-wagon”) and transfer our freight of mails.

Presently we got under way again. We came to the shallow, yellow, muddy South Platte, with its low banks and its scattering flat sand-bars and pigmy islands—a melancholy stream straggling through the centre of the enormous flat plain, and only saved from being impossible to find with the naked eye by its sentinel rank of scattering trees standing on either bank. The Platte was “up,” they said—which made me wish I could see it when it was down, if it could look any sicker and sorrier. They said it was a dangerous stream to cross, now, because its quicksands were liable to swallow up horses, coach and passengers if an attempt was made to ford it. But the mails had to go, and we made the attempt. Once or twice in midstream the wheels sunk into the yielding sands so threateningly that we half believed we had dreaded and avoided the sea all our lives to be shipwrecked in a “mud-wagon” in the middle of a desert at last. But we dragged through and sped away toward the setting sun.

Next morning, just before dawn, when about five hundred and fifty miles from St. Joseph, our mud-wagon broke down. We were to be delayed five or six hours, and therefore we took horses, by invitation, and joined a party who were just starting on a buffalo hunt. It was noble sport galloping over the plain in the dewy freshness of the morning, but our part of the hunt ended in disaster and disgrace, for a wounded buffalo bull chased the passenger Bemis nearly two miles, and then he forsook his horse and took to a lone tree. He was very sullen about the matter for some twenty-four hours, but at last he began to soften little by little, and finally he said:

“Well, it was not funny, and there was no sense in those gawks making themselves so facetious over it. I tell you I was angry in earnest for awhile. I should have shot that long gangly lubber they called Hank, if I could have done it without crippling six or seven other people—but of course I couldn’t, the old ‘Allen’s’ so confounded comprehensive. I wish those loafers had been up in the tree; they wouldn’t have wanted to laugh so. If I had had a horse worth a cent—but no, the minute he saw that buffalo bull wheel on him and give a bellow, he raised straight up in the air and stood on his heels. The saddle began to slip, and I took him round the neck and laid close to him, and began to pray. Then he came down and stood up on the other end awhile, and the bull actually stopped pawing sand and bellowing to contemplate the inhuman spectacle. Then the bull made a pass at him and uttered a bellow that sounded perfectly frightful, it was so close to me, and that seemed to literally prostrate my horse’s reason, and make a raving distracted maniac of him, and I wish I may die if he didn’t stand on his head for a quarter of a minute and shed tears. He was absolutely out of his mind—he was, as sure as truth itself, and he really didn’t know what he was doing. Then the bull came charging at us, and my horse dropped down on all fours and took a fresh start—and then for the next ten minutes he would actually throw one hand-spring after another so fast that the bull began to get unsettled, too, and didn’t know where to start in—and so he stood there sneezing, and shovelling dust over his back, and bellowing every now and then, and thinking he had got a fifteen-hundred dollar circus horse for breakfast, certain. Well, I was first out on his neck—the horse’s, not the bull’s—and then underneath, and next on his rump, and sometimes head up, and sometimes heels—but I tell you it seemed solemn and awful to be ripping and tearing and carrying on so in the presence of death, as you might say. Pretty soon the bull made a snatch for us and brought away some of my horse’s tail (I suppose, but do not know, being pretty busy at the time), but something made him hungry for solitude and suggested to him to get up and hunt for it. And then you ought to have seen that spider-legged old skeleton go! and you ought to have seen the bull cut out after him, too—head down, tongue out, tail up, bellowing like everything, and actually mowing down the weeds, and tearing up the earth, and boosting up the sand like a whirlwind! By George, it was a hot race! I and the saddle were back on the rump, and I had the bridle in my teeth and holding on to the pommel with both hands. First we left the dogs behind; then we passed a jackass rabbit; then we overtook a cayote, and were gaining on an antelope when the rotten girth let go and threw me about thirty yards off to the left, and as the saddle went down over the horse’s rump he gave it a lift with his heels that sent it more than four hundred yards up in the air, I wish I may die in a minute if he didn’t. I fell at the foot of the only solitary tree there was in nine counties adjacent (as any creature could see with the naked eye), and the next second I had hold of the bark with four sets of nails and my teeth, and the next second after that I was astraddle of the main limb and blaspheming my luck in a way that made my breath smell of brimstone. I had the bull, now, if he did not think of one thing. But that one thing I dreaded. I dreaded it very seriously. There was a possibility that the bull might not think of it, but there were greater chances that he would. I made up my mind what I would do in case he did. It was a little over forty feet to the ground from where I sat. I cautiously unwound the lariat from the pommel of my saddle—”

“Your saddle? Did you take your saddle up in the tree with you?”

“Take it up in the tree with me? Why, how you talk. Of course I didn’t. No man could do that. It fell in the tree when it came down.”

“Oh—exactly.”

“Certainly. I unwound the lariat, and fastened one end of it to the limb. It was the very best green raw-hide, and capable of sustaining tons. I made a slip-noose in the other end, and then hung it down to see the length. It reached down twenty-two feet—half way to the ground. I then loaded every barrel of the Allen with a double charge. I felt satisfied. I said to myself, if he never thinks of that one thing that I dread, all right—but if he does, all right anyhow—I am fixed for him. But don’t you know that the very thing a man dreads is the thing that always happens? Indeed it is so. I watched the bull, now, with anxiety—anxiety which no one can conceive of who has not been in such a situation and felt that at any moment death might come. Presently a thought came into the bull’s eye. I knew it! said I—if my nerve fails now, I am lost. Sure enough, it was just as I had dreaded, he started in to climb the tree—”

“What, the bull?”

“Of course—who else?”

“But a bull can’t climb a tree.”

“He can’t, can’t he? Since you know so much about it, did you ever see a bull try?” “No! I never dreamt of such a thing.”

“Well, then, what is the use of your talking that way, then? Because you never saw a thing done, is that any reason why it can’t be done?”

“Well, all right—go on. What did you do?”

“The bull started up, and got along well for about ten feet, then slipped and slid back. I breathed easier. He tried it again—got up a little higher—slipped again. But he came at it once more, and this time he was careful. He got gradually higher and higher, and my spirits went down more and more. Up he came—an inch at a time—with his eyes hot, and his tongue hanging out. Higher and higher— hitched his foot over the stump of a limb, and looked up, as much as to say, ‘You are my meat, friend.’ Up again—higher and higher, and getting more excited the closer he got. He was within ten feet of me! I took a long breath,—and then said I, ‘It is now or never.’ I had the coil of the lariat all ready; I paid it out slowly, till it hung right over his head; all of a sudden I let go of the slack, and the slipnoose fell fairly round his neck! Quicker than lightning I out with the Allen and let him have it in the face. It was an awful roar, and must have scared the bull out of his senses. When the smoke cleared away, there he was, dangling in the air, twenty foot from the ground, and going out of one convulsion into another faster than you could count! I didn’t stop to count, anyhow—I shinned down the tree and shot for home.”

“Bemis, is all that true, just as you have stated it?”

“I wish I may rot in my tracks and die the death of a dog if it isn’t.”

“Well, we can’t refuse to believe it, and we don’t. But if there were some proofs—”

“Proofs! Did I bring back my lariat?”

“No.”

“Did I bring back my horse?”

“No.”

“Did you ever see the bull again?”

“No.”

“Well, then, what more do you want? I never saw anybody as particular as you are about a little thing like that.”

I made up my mind that if this man was not a liar he only missed it by the skin of his teeth. This episode reminds me of an incident of my brief sojourn in Siam, years afterward. The European citizens of a town in the neighborhood of Bangkok had a prodigy among them by the name of Eckert, an Englishman—a person famous for the number, ingenuity and imposing magnitude of his lies. They were always repeating his most celebrated falsehoods, and always trying to “draw him out” before strangers; but they seldom succeeded. Twice he was invited to the house where I was visiting, but nothing could seduce him into a specimen lie. One day a planter named Bascom, an influential man, and a proud and sometimes irascible one, invited me to ride over with him and call on Eckert. As we jogged along, said he:

“Now, do you know where the fault lies? It lies in putting Eckert on his guard. The minute the boys go to pumping at Eckert he knows perfectly well what they are after, and of course he shuts up his shell. Anybody might know he would. But when we get there, we must play him finer than that. Let him shape the conversation to suit himself—let him drop it or change it whenever he wants to. Let him see that nobody is trying to draw him out. Just let him have his own way. He will soon forget himself and begin to grind out lies like a mill. Don’t get impatient—just keep quiet, and let me play him. I will make him lie. It does seem to me that the boys must be blind to overlook such an obvious and simple trick as that.”

Eckert received us heartily—a pleasant-spoken, gentle-mannered creature. We sat in the veranda an hour, sipping English ale, and talking about the king, and the sacred white elephant, the Sleeping Idol, and all manner of things; and I noticed that my comrade never led the conversation himself or shaped it, but simply followed Eckert’s lead, and betrayed no solicitude and no anxiety about anything. The effect was shortly perceptible. Eckert began to grow communicative; he grew more and more at his ease, and more and more talkative and sociable. Another hour passed in the same way, and then all of a sudden Eckert said:

“Oh, by the way! I came near forgetting. I have got a thing here to astonish you. Such a thing as neither you nor any other man ever heard of—I’ve got a cat that will eat cocoanut! Common green cocoanut—and not only eat the meat, but drink the milk. It is so—I’ll swear to it.”

A quick glance from Bascom—a glance that I understood—then:

“Why, bless my soul, I never heard of such a thing. Man, it is impossible.”

“I knew you would say it. I’ll fetch the cat.”

He went in the house. Bascom said:

“There—what did I tell you? Now, that is the way to handle Eckert. You see, I have petted him along patiently, and put his suspicions to sleep. I am glad we came. You tell the boys about it when you go back. Cat eat a cocoanut—oh, my! Now, that is just his way, exactly—he will tell the absurdest lie, and trust to luck to get out of it again. Cat eat a cocoanut—the innocent fool!”

Eckert approached with his cat, sure enough. Bascom smiled. Said he: “I’ll hold the cat—you bring a cocoanut.”

Eckert split one open, and chopped up some pieces. Bascom smuggled a wink to me, and proffered a slice of the fruit to puss. She snatched it, swallowed it ravenously, and asked for more!

We rode our two miles in silence, and wide apart. At least I was silent, though Bascom cuffed his horse and cursed him a good deal, notwithstanding the horse was behaving well enough. When I branched off homeward, Bascom said:

“Keep the horse till morning. And—you need not speak of this—foolishness to the boys.”

CHAPTER XIV

Mr. Street was very busy with his telegraphic matters —and considering that he had eight or nine hundred miles of rugged, snowy, uninhabited mountains, and waterless, treeless, melancholy deserts to traverse with his wire, it was natural and needful that he should be as busy as possible. He could not go comfortably along and cut his poles by the roadside, either, but they had to be hauled by ox teams across those exhausting deserts—and it was two days’ journey from water to water, in one or two of them. Mr. Street’s contract was a vast work, every way one looked at it; and yet to comprehend what the vague words “eight hundred miles of rugged mountains and dismal deserts” mean, one must go over the ground in person—pen and ink descriptions cannot convey the dreary reality to the reader. And after all, Mr. S.’s mightiest difficulty turned out to be one which he had never taken into the account at all. Unto Mormons he had sub-let the hardest and heaviest half of his great undertaking, and all of a sudden they concluded that they were going to make little or nothing, and so they tranquilly threw their poles overboard in mountain or desert, just as it happened when they took the notion, and drove home and went about their customary business! They were under written contract to Mr. Street, but they did not care anything for that. They said they would “admire” to see a “Gentile” force a Mormon to fulfil a losing contract in Utah! And they made themselves very merry over the matter. Street said—for it was he that told us these things: “I was in dismay. I was under heavy bonds to complete my contract in a given time, and this disaster looked very much like ruin. It was an astounding thing; it was such a wholly unlooked-for difficulty, that I was entirely nonplussed. I am a business man—have always been a business man—do not know anything but business—and so you can imagine how like being struck by lightning it was to find myself in a country where written contracts were worthless!—that main security, that sheet-anchor, that absolute necessity, of business. My confidence left me. There was no use in making new contracts—that was plain. I talked with first one prominent citizen and then another. They all sympathized with me, first rate, but they did not know how to help me. But at last a Gentile said, ‘Go to Brigham Young!—these small fry cannot do you any good.’ I did not think much of the idea, for if the law could not help me, what could an individual do who had not even anything to do with either making the laws or executing them? He might be a very good patriarch of a church and preacher in its tabernacle, but something sterner than religion and moral suasion was needed to handle a hundred refractory, half-civilized sub-contractors. But what was a man to do? I thought if Mr. Young could not do anything else, he might probably be able to give me some advice and a valuable hint or two, and so I went straight to him and laid the whole case before him. He said very little, but he showed strong interest all the way through. He examined all the papers in detail, and whenever there seemed anything like a hitch, either in the papers or my statement, he would go back and take up the thread and follow it patiently out to an intelligent and satisfactory result. Then he made a list of the contractors’ names. Finally he said:

“‘Mr. Street, this is all perfectly plain. These contracts are strictly and legally drawn, and are duly signed and certified. These men manifestly entered into them with their eyes open. I see no fault or flaw anywhere.’ Then Mr. Young turned to a man waiting at the other end of the room and said: ‘Take this list of names to Soand-so, and tell him to have these men here at such-and-such an hour.’

“They were there, to the minute. So was I. Mr. Young asked them a number of questions, and their answers made my statement good. Then he said to them:

“‘You signed these contracts and assumed these obligations of your own free will and accord?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Then carry them out to the letter, if it makes paupers of you! Go!’ And they did go, too! They are strung across the deserts now, working like bees. And I never hear a word out of them. There is a batch of governors, and judges, and other officials here, shipped from Washington, and they maintain the semblance of a republican form of government—but the petrified truth is that Utah is an absolute monarchy and Brigham Young is king!”

Mr. Street was a fine man, and I believe his story. I knew him well during several years afterward in San Francisco.

Our stay in Salt Lake City amounted to only two days, and therefore we had no time to make the customary inquisition into the workings of polygamy and get up the usual statistics and deductions preparatory to calling the attention of the nation at large once more to the matter. I had the will to do it. With the gush ing self-sufficiency of youth I was feverish to plunge in headlong and achieve a great reform here—until I saw the Mormon women. Then I was touched. My heart was wiser than my head. It warmed toward these poor, ungainly and pathetically “homely” creatures, and as I turned to hide the generous moisture in my eyes, I said, “No—the man that marries one of them has done an act of Christian charity which entitles him to the kindly applause of mankind, not their harsh censure— and the man that marries sixty of them has done a deed of open-handed generosity so sublime that the nations should stand uncovered in his presence and worship in silence.”

“The War Prayer”

It was a time of great and exalting excitement.

The country was up in arms, the war was on, in every breast burned the holy fire of patriotism; the drums were beating, the bands playing, the toy pistols popping, the bunched firecrackers hissing and spluttering; on every hand and far down the receding and fading spread of roofs and balconies a fluttering wilderness of flags flashed in the sun; daily the young volunteers marched down the wide avenue gay and fine in their new uniforms, the proud fathers and mothers and sisters and sweethearts cheering them with voices choked with happy emotion as they swung by; nightly the packed mass meetings listened, panting, to patriot oratory which stirred the deepest deeps of their hearts, and which they interrupted at briefest intervals with cyclones of applause, the tears running down their cheeks the while; in the churches the pastors preached devotion to flag and country, and invoked the God of Battles beseeching His aid in our good cause in outpourings of fervid eloquence which moved every listener. It was indeed a glad and gracious time, and the half dozen rash spirits that ventured to disapprove of the war and cast a doubt upon its righteousness straightway got such a stern and angry warning that for their personal safety’s sake they quickly shrank out of sight and offended no more in that way.

Sunday morning came—next day the battalions would leave for the front; the church was filled; the volunteers were there, their young faces alight with martial dreams—visions of the stern advance, the gathering momentum, the rushing charge, the flashing sabers, the flight of the foe, the tumult, the enveloping smoke, the fierce pursuit, the surrender! Then home from the war, bronzed heroes, welcomed, adored, submerged in golden seas of glory! With the volunteers sat their dear ones, proud, happy, and envied by the neighbors and friends who had no sons and brothers to send forth to the field of honor, there to win for the flag, or, failing, die the noblest of noble deaths. The service proceeded; a war chapter from the Old Testament was read; the first prayer was said; it was followed by an organ burst that shook the building, and with one impulse the house rose, with glowing eyes and beating hearts, and poured out that tremendous invocation

God the all-terrible!

Thou who ordainest!

Thunder thy clarion

and lightning thy sword!

Then came the “long” prayer. None could remember the like of it for passionate pleading and moving and beautiful language. The burden of its supplication was, that an ever-merciful and benignant Father of us all would watch over our noble young soldiers, and aid, comfort, and encourage them in their patriotic work; bless them, shield them in the day of battle and the hour of peril, bear them in His mighty hand, make them strong and confident, invincible in the bloody onset; help them to crush the foe, grant to them and to their flag and country imperishable honor and glory—

An aged stranger entered and moved with slow and noiseless step up the main aisle, his eyes fixed upon the minister, his long body clothed in a robe that reached to his feet, his head bare, his white hair descending in a frothy cataract to his shoulders, his seamy face unnaturally pale, pale even to ghastliness. With all eyes following him and wondering, he made his silent way; without pausing, he ascended to the preacher’s side and stood there waiting. With shut lids the preacher, unconscious of his presence, continued with his moving prayer, and at last finished it with the words, uttered in fervent appeal, “Bless our arms, grant us the victory, O Lord our God, Father and Protector of our land and flag!”

The stranger touched his arm, motioned him to step aside—which the startled minister did—and took his place. During some moments he surveyed the spellbound audience with solemn eyes, in which burned an uncanny light; then in a deep voice he said:

“I come from the Throne—bearing a message from Almighty God!” The words smote the house with a shock; if the stranger perceived it he gave no attention. “He has heard the prayer of His servant your shepherd, and will grant it if such shall be your desire after I, His messenger, shall have explained to you its import—that is to say, its full import. For it is like unto many of the prayers of men, in that it asks for more than he who utters it is aware of—except he pause and think.

“God’s servant and yours has prayed his prayer. Has he paused and taken thought? Is it one prayer? No, it is two—one uttered, the other not. Both have reached the ear of Him Who heareth all supplications, the spoken and the unspoken. Ponder this—keep it in mind. If you would beseech a blessing upon yourself, beware! lest without intent you invoke a curse upon a neighbor at the same time. If you pray for the blessing of rain upon your crop which needs it, by that act you are possibly praying for a curse upon some neighbor’s crop which may not need rain and can be injured by it.

“You have heard your servant’s prayer—the uttered part of it. I am commissioned of God to put into words the other part of it—that part which the pastor— and also you in your hearts—fervently prayed silently. And ignorantly and unthinkingly? God grant that it was so! You heard these words: ‘Grant us the victory, O Lord our God!’ That is sufficient. The whole of the uttered prayer is compact into those pregnant words. Elaborations were not necessary. When you have prayed for victory you have prayed for many unmentioned results which follow victory— must follow it, cannot help but follow it. Upon the listening spirit of God fell also the unspoken part of the prayer. He commandeth me to put it into words. Listen!

“O Lord our Father, our young patriots, idols of our hearts, go forth to battle— be Thou near them! With them—in spirit—we also go forth from the sweet peace of our beloved firesides to smite the foe. O Lord our God, help us to tear their soldiers to bloody shreds with our shells; help us to cover their smiling fields with the pale forms of their patriot dead; help us to drown the thunder of the guns with the shrieks of their wounded, writhing in pain; help us to lay waste their humble homes with a hurricane of fire; help us to wring the hearts of their unoffending widows with unavailing grief; help us to turn them out roofless with little children to wander unfriended the wastes of their desolated land in rags and hunger and thirst, sports of the sun flames of summer and the icy winds of winter, broken in spirit, worn with travail, imploring Thee for the refuge of the grave and denied it—for our sakes who adore Thee, Lord, blast their hopes, blight their lives, protract their bitter pilgrimage, make heavy their steps, water their way with their tears, stain the white snow with the blood of their wounded feet! We ask it, in the spirit of love, of Him Who is the Source of Love, and Who is the ever-faithful refuge and friend of all that are sore beset and seek His aid with humble and contrite hearts. Amen.

(After a pause.) “Ye have prayed it; if ye still desire it, speak! The messenger of the Most High waits!”

It was believed afterward that the man was a lunatic, because there was no sense in what he said.

Reading and Review Questions

- In “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” what is Jim Smiley’s talent? Why does he lose it?

- Would you consider Mark Twain an experimental writer? How are his stories different from other authors of his time period?

- In Twain’s “War Prayer,” how do the town’s people react to the prophet? Is his message clear? How is this a controversial story?