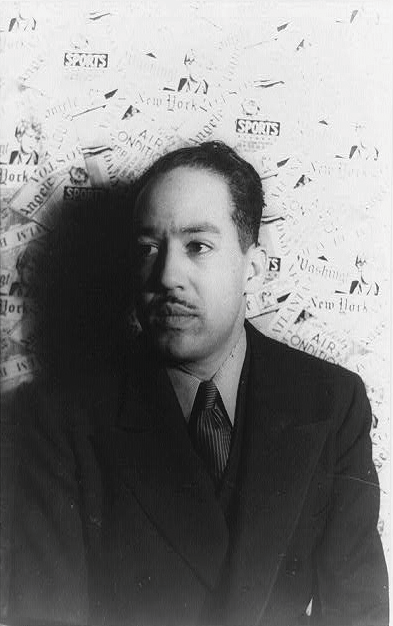

Langston Hughes (1902-1967)

Langston Hughes, 1936

Photographer | Carl Van Vechten

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

“We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame,” Langston Hughes writes in his 1926 manifesto for the younger generation of Harlem Renaissance artists, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” He continues, “If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful.” Celebrated as “the poet laureate of Harlem,” Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, and traveled extensively before settling in the neighborhood he came to call home. When growing up, Hughes lived variously with his grandmother in Lawrence, Kansas, his father in Mexico, and his mother in Washington, D.C. After just one year at Columbia University, Hughes left college to explore the world, working as a cabin boy on ships bound for Africa and as a cook in a Paris kitchen. Throughout these early years, Hughes published poems in the African-American magazines The Crisis and Opportunity; these poems soon earned him recognition as a rising star of the Harlem Renaissance who excelled at the lyrical use of the music, speech, and experiences of urban, working-class African-Americans. Hughes published his first book of poetry, The Weary Blues, at the age of twenty-four while still a student at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. Over the course of his long and influential literary career, Hughes worked extensively in all areas of African-American literature, writing novels, short stories, plays, essays, and works of history; translating work by black authors; and editing numerous anthologies of African-American history and culture, such as The First Book of Jazz (1955) and The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers (1969).

Hughes’s poems embody one of the major projects of the Harlem Renaissance: to create distinctively African-American art. By the turn of the twentieth century, African-Americans had awakened to the realization that two hundred years of slavery had simultaneously erased their connections to their African heritage and created, in its wake, new, vital forms of distinctively African-American culture. Accordingly, politicians, authors, and artists associated with the Harlem Renaissance reconstructed that lost history and championed art rooted in the black American experience. Hughes’s poems from the 1920s are particularly notable for celebrating black culture while also honestly representing the deprivations of working-class African-American life. In “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” Hughes connects African-American culture to the birth of civilization in Africa and the Middle East. In “Mother to Son,” Hughes draws upon the music of the blues and black dialect to celebrate the indomitable heart of working black America. Hughes grew increasingly radicalized in the 1930s following such high-profile examples of American racism as the 1931 Scottsboro trial in Alabama. He travelled to the Soviet Union in 1932 to work on an unfinished film about race in the American South and published in leftist publications associated with the American Communist Party, the only political party at the time to oppose segregation. “Christ in Alabama” is a good example of Hughes’s more pointed political style, in which the poet criticizes the immorality of racism by equating the suffering of African-Americans in Alabama with the suffering of Christ. Poems such as “I, too,” and “Theme for English B,” in turn, combine Hughes’s provocative politics with his cultural lyricism to articulate a theme that runs throughout his life’s work: that the American experience is as black as it is white.

“Christ in Alabama”

Please click the link below to access this selection:

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma05/dulis/poetry/Hughes/hughes2.html

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers”

I’ve known rivers

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

“Theme for English b”

Please click the link below to access this selection:

http://www.eecs.harvard.edu/~keith/poems/English_B.html

Reading and Review Questions

- What is significant about the rivers—the Euphrates, the Congo, the Nile, and the Mississippi—that Hughes names in “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”?

- Jesus Christ is often represented as being white in Western art. What does Hughes’s identification of Christ as “a nigger” say about the Christians of the segregated American South of the early twentieth century?

- The semi-autobiographical poem “Theme for English B” was first published in 1946, decades after Hughes attended his one year of college at Columbia “on the hill above Harlem.” However, Hughes writes the poem not in the past tense but in the present tense. How does Hughes’s use of the present tense affect the meaning of the poem?