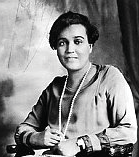

Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882-1961)

Jessie Redmon Fauset, n.d.

Photographer | Unknown

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Fair Use

Jessie Redmon Fauset, like her younger contemporary Countee Cullen, belongs to the first generation of Harlem Renaissance writers who used traditional literary forms to explore issues important to the African-American community. In this way, the growth of these writers can be likened to the path traced by nineteenth-century British women writers and outlined in Elaine Showalter’s book A Literature of Their Own (1977). In her study of women writers, Showalter traced three stages of literary development. In the first stage, underrepresented authors use traditional forms and adopt traditional viewpoints in order to gain wider acceptance. In the second stage, authors begin to use traditional forms to advance new viewpoints while, in the third stage, authors adopt new forms to advance progressive viewpoints. In many ways, these same three stages that Showalter assigned to British women writers of the nineteenth century can be applied to the writers of the Harlem Renaissance. Both Fauset and Cullen can be classified as second stage writers: those who used traditional forms to celebrate new ideas.

For much of the early twentieth century, Fauset was the literary editor of The Crisis, and her selections, as well as her own writing, adhered to W. E. B. Du Bois’s mission statement for the magazine:

The object of this publication is to set forth those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested today toward colored people. The policy of The Crisis will be simple and well defined: It will first and foremost be a newspaper, Secondly it will be a review of opinion and literature, . . . Thirdly it will publish a few short articles, Finally, its editorial page will stand for the right of men, irrespective of color or race, for the highest ideals of American democracy, and for reasonable but earnest and persistent attempt to gain these rights and realize these ideals. The Magazine will be the organ of no clique or party and will avoid personal rancor of all sorts. In the absence of proof to the contrary it will assume honesty of purpose on the part of all men, North and South, white and black.5

As the first African-American elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society at Cornell University (1905) and as a master’s graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Fauset was well positioned to advance Du Bois’s goals. Like Cullen and other early members of the Harlem Renaissance, Fauset was an articulate voice for a certain segment of the African-American community.

While Fauset’s relatively privileged position granted her access to mainstream literary circles of her time, this same privilege ultimately alienated her from other members of the Harlem Renaissance. Many of Fauset’s works concern the struggles of light-skinned, middle-class African-Americans to assimilate and succeed over the limitations of their racial identities, and this largely positive portrayal of assimilation and passing angered other members of the movement like Langston Hughes who argued for a full embrace of African-American racial identity.

The selection from Fauset, “The Sleeper Wakes” (1920), challenges both our preconceptions about Fauset and the attacks on her by Hughes. Although the story directly concerns the life of a light-skinned African-American who is married to a white husband, Fauset’s heroine, Amy, is ultimately unsettled by her success at passing. Stirred to action by her husband’s mistreatment of an African-American servant, Amy recognizes her racial identity and awakens as the title suggests. Awakened to her racial identity, Amy leaves her husband and his money behind in order to live a more direct representation of her identity. Although Fauset and Cullen both embrace traditional literary forms, their presentation of race demonstrates their active engagement with issues of identity, politics, and the promises of the American experiment that are more progressive than their forms suggest.

5.19.1 “The Sleeper Wakes”

Amy recognized the incident as the beginning of one of her phases. Always from a child she had been able to tell when “something was going to happen.” She had been standing in Marshall’s store, her young, eager gaze intent on the lovely little sample dress which was not from Paris, but quite as dainty as anything that Paris could produce. It was not the lines or even the texture that fascinated Amy so much, it was the grouping of colors—of shades. She knew the combination was just right for her.

Let me slip it on, Miss,” said the saleswoman suddenly. She had nothing to do just then, and the girl was so evidently charmed and so pretty—it was a pleasure to wait on her.

“Oh no,” Amy had stammered. “I haven’t time.” She had already wasted two hours at the movies, and she knew at home they were waiting for her.

The saleswoman slipped the dress over the girl’s pink blouse, and tucked the linen collar under so as to bring the edge of the dress next to her pretty neck. The dress was apricot-color shading into a shell pink and the shell pink shaded off again into the pearl and pink whiteness of Amy’s skin. The saleswoman beamed as Amy, entranced, surveyed herself naively in the tall looking-glass.

Then it was that the incident befell. Two men walking idly through the dress-salon stopped and looked—she made an unbelievably pretty picture. One of them with a short, soft brown beard,—”fuzzy” Amy thought to herself as she caught his glance in the mirror—spoke to his companion.

“Jove, how I’d like to paint her!” But it was the look on the other man’s face that caught her and thrilled her. “My God! Can’t a girl be beautiful!” he said half to himself. The pair passed on.

Amy stepped out of the dress and thanked the saleswoman half absently. She wanted to get home and think, think to herself about that look. She had seen it before in men’s eyes, it had been in the eyes of the men in the moving-picture which she had seen that afternoon. But she had not thought she could cause it. Shut up in her little room, she pondered over it. Her beauty,—she was really good-looking then—she could stir people—men! A girl of seventeen has no psychology, she does not go beneath the surface, she accepts. But she knew she was entering on one of her phases.

She was always living in some sort of story. She had started it when as a child of five she had driven with the tall, proud, white woman to Mrs. Boldin’s home. Mrs. Boldin was a bride of one year’s standing then. She was slender and very, very comely, with her rich brown skin and her hair that crinkled thick and soft above a low forehead. The house was still redolent of new furnoiture; Mr. Boldin was spick and span—he, unlike the furniture, remained so for that matter. The white woman had told Amy that this henceforth was to be her home.

Amy was curious, fond of adventure; she did not cry. She did not, of course, realize that she was to stay here indefinitely, but if she had, even at that age she would hardly have shed tears, she was always too eager, too curious to know, to taste what was going to happen next. Still since she had had almost no dealings with colored people and knew absolutely none of the class to which Mrs. Boldin belonged, she did venture one question.

“Am I going to be colored now?”

The tall white woman had flushed and paled. “You—” she began, but the words choked her. “Yes, you are going to be colored now,” she ended finally. She was a proud woman, in a moment she had recovered her usual poise. Amy carried with her for many years the memory of that proud head. She never saw her again.

When she was sixteen she asked Mrs. Boldin the question which in the light of that memory had puzzled her always. “Mrs. Boldin, tell me—am I white or colored?”

And Mrs. Boldin had told her and told her truly that she did not know.

“A—a—mee!” Mrs. Bolding’s voice mounted on the last syllable in a shrill crescendo. Amy rose and went downstairs.

Down in the comfortable, but rather shabby dining-room which the Boldins used after meals to sit in, Mr. Boldin, a tall black man, with aristocratic features, sat reading; little Cornelius Boldin sat practicing on a cornet, and Mrs. Boldin sat rocking. In all of their eyes was the manifestation of the light that Amy loved, but how truly she loved it, she was not to guess till years later.

“Amy,” Mr. Boldin paused in her rocking, “did you get the braid?” Of couse she had not, though that was the thing she had gone to Marshall’s for. Amy always went willingly, it was for the pure joy of going. Who knew what angels might meet one unawares? Not that Amy though in biblical or in literary phrases. She was in the High School, it is true, but she was simply passing through, “getting by” she would have said carelessly. The only reading that had ever made any impression on her had been fairy tales read to her in those long remote days when she had lived with the tall, proud woman; and descriptions in novels or histories of beautiful stately palaces tenanted by beautiful, stately women. She could pore over such pages for hours, her face flushed, her eyes eager.

At present she cast about for an excuse. She had so meant to get the braid. “There was a dress—” she began lamely, she was never deliberately dishonest.

Mr. Boldin cleared his throat and nervously fingered his paper. Cornelius ceased his awful playing and blinked at her shortsightedly through his thick glasses. Both of these, the man and the little boy, loved the beautiful, inconsequential creature with her airy, irresponsible ways. But Mrs. Boldin loved her too, and because she loved her she could not scold.

“Of course you forgot,” she began chidingly. Then she smiled. “There was a dress that you looked at perhaps. But confess, didn’t you go to the movies first?”

Yes, Amy confessed she had done just that. “And oh, Mrd. Boldin, it was the most wonderful picture—a girl—such a pretty one—and she was poor, awfully. And somehow se met the most wonderful people and they were so kind to her. And she married a man who was just tremendously rich and he gave her everything. I did so want Cornelius to see it.”

“Huh!” said Cornelius who had been listening not because he was interested, but because he wanted to call Amy’s attention to his playing as soon as possible. “Huh! I don’t want to look at no pretty girl. Did they have anybody looping the loop in an airship?”

“You’d better stop seeing pretty girl pictures, Amy,” said Mr. Boldin kindly. “They’re not always true to life. Besides, I know where you can see all the pretty girls you want without bothering to pay twenty-five cents for it.”

Amy smiled at the implied compliment and went on happily studying her lessons. They were all happy in their own way. Amy because she was sure of their love and admiration, Mr. and Mrs. Boldin because of her beauty and innocence and Cornelius because he knew he had in his foster-sister a listener whom his terrible practicing could never bore. He played brokenly a piece he had found in an old music-book. “There’s an aching void in every heart, brother.”

“Where do you pick up those old things, Neely?” said his mother fretfully. But Amy could not have her favorite’s feelings injured.

“I think it’s lovely,” she announced defensively. “Cornelius, I’ll ask Sadie Murray to lend me her brother’s book. He’s learning the cornet, too, and you can get some new pieces. Of, isn’t it awful to have to go to bed? Good-night, everybody.” She smiled her charming, ever ready smile, the mere reflex of youth and beauty and content.

“You do spoil her, Mattie,” said Mr. Boldin after she had left the room. “She’s only seventeen—here, Cornelius, you go to bed—but it seems to me she ought to be more dependable about errands. Though she is splendid about some things,” he defended her. “Look how willingly she goes off to bed. She’ll be asleep before she knows it when most girls of her age would want to be in the street.”

But upstairs Amy was far from sleep. She lit on gas-jet and pulled down the shades. Then she stuffed tissue paper in the keyhole and under the doors, and lit the remaining gas-jets. The light thus thrown on the mirror of the ugly oak dresser was perfect. She slipped off the pink blouse and found two scarfs, a soft yellow and soft pink,— se had had them in a scarf-dance for a school entertainment. She wound them and draped them about her pretty shoulders and loosened her hair. In the mirror she apostrophized the beautiful, glowing vision of herself.

“There,” she said, “I’m like the girl in the picture. She had nothing but her beautiful face—and she did so want to be happy.” She sat down on the side of the rather lumpy bed and stretched out her arms. “I want to be happy, too.” She intoned it earnestly, almost like an incantation. “I want wonderful clothes, and people around me, men adoring me, and the world before me. I want—everything! It will come, it will all come because I want it so.” She sat frowning intently as she was apt to do when very much engrossed. “And we’d all be so happy. I’d give Mr. and Mrs. Boldin money! And Cornelius—he’d go to college and learn all about his old airships. Oh, if I only knew how to begin!”

Smiling, she turned off the lights and crept to bed.

II

Quite suddenly she knew she was going to run away. That was in October. By December she had accomplished her purpose. Not that she was to least bit unhappy but because she must get out in the world,—she felt caged, imprisoned. “Trenton is stifling me,” she would have told you, in her unconsciously adopted “movie” diction. New York she knew was the place for her. She had her plans all made. She had sewed steadily after school for two months—as she frequently did when she wanted to buy her season’s wardrobe, so besides her carfare she had $25. She went immediately to a white Y. W. C. A., stayed there two nights, found and answered an advertisement for clerk and waitress in a small confectionery and bakery-shop, was accepted and there she was launched.

Perhaps it was because of her early experience when as a tiny child she was taken from that so different home and left at Mrs. Boldin’s, perhaps it was some fault in her own disposition, concentrated and egotistic as she was, but certainly she felt no pangs of separation, no fear of her future. She was cold too,—unfired though so to speak rather than icy,—and fastidious. This last quality kept her safe where morality or religion, of neither of which had she any conscious endowment, would have availed her nothing. Unbelievably then she lived two years in New York, unspoiled, untouched going to her work on the edge of Greenwich Village early and coming back late, knowing almost no one and yet altogether happy in the expectation of something wonderful, which she knew some day must happen.

It was at the end of the second year that she met Zora Harrisson. Zora used to come into lunch with a group of habitués of the place—all of them artists and writers Amy gathered. Mrs. Harrisson (for she was married as Amy later learned) appealed to the girl because she knew so well how to afford the contrast to her blonde, golden beauty. Purple, dark and regal, developed in velvets and heavy silks, and strange marine blues she wore, and thus made Amy absolutely happy. Singularly enough, the girl intent as she was on her own life and experiences, had felt up to this time no yearning to know these strange, happy beings who surrounded her. She did miss Cornelius, but otherwise she was never lonely, or if she was she hardly knew it, for she had always lived an inner life to herself. But Mrs. Harrisson magnetized her—she could not keep her eyes from her face, from her wonderful clothes. She made conjectures about her.

The wonderful lady came in late one afternoon—an unusual thing for her. She smiled at Amy invitingly, asked some banal questions and their first conversation began. The acquaintance once struck up progressed rapidly—after a few weeks Mrs. Harrisson invited the girl to come to see her. Amy accepted quietly, unaware that anything extraordinary was happening. Zora noticed this and liked it. She had an apartment in 12th Street in a house inhabited only by artists—she was no mean one herself. Amy was fascinated by the new world into which she found herself ushered; Zora’s surroundings were very beautiful and Zora herself was a study. She opened to the girl’s amazed vision fields of thought and conjecture, phases of whose existence Amy, who was a builder of phases, had never dreamed. Zora had been a poor girl of good family. She had wanted to study art, she had deliberately married a rich man and as deliberately obtained in the course of four years a divorce, and she was now living in New York studying by means of her alimony and enjoying to its fullest the life she loved. She took Amy on a footing with herself—the girl’s refinement, her beauty, her interest in colors (though this in Amy at the time was purely sporadic, never consciously encouraged), all this gave Zora a figure about which to plan and build a romance. Amy had told her to truth, but not all about her coming to New York. She had grown tired of Trenton—her people were all dead—the folks with whom she lived were kind and good but not “inspiring” (she had borrowed the term from Zora and it was true, the Boldins, when one came to think of it, were not “inspiring”), so she had run away.

Zora had gone into raptures. “What an adventure! My dear, the world is yours. Why, with your looks and your birth, for I suppose you really belong to the Kildares who used to live in Philadelphia, I think there was a son who ran off and married an actress or someone—they disowned him I remember,—you can reach any height. You must marry a wealthy man—perhaps someone who is interested in art and who will let you pursue your studies.” She insisted always that Amy had run away in order to study art. “But luck like that comes to few,” she sighed, remembering her own plight, for Mr. Harrisson had been decidedly unwilling to let her pursue her studies, at least to the extent she wished. “Anyway you must marry wealth,—one can always get a divorce,” she ended sagely.

Amy—she came to Zora’s every night now—used to listen dazedly at first. She had accepted willingly enough Zora’s conjecture about her birth, came to believe it in fact—but she drew back somewhat at such wholesale exploitation of people to suit one’s own convenience, still she did not probe too far into this thought—nor did she grasp at all the infamy of exploitation of self. She ventured one or two objections, however, but Zora brushed everything aside.

“Everybody is looking out for himself,” she said airily. “I am interested in you, for instance, not for philanthropy’s sake, but because I am lonely, and you are charming and pretty and don’t get tired of hearing me talk. You’d better come and live with me awhile, my dear, six months or a year. It doesn’t cost any more for two than for one, and you can always leave when we get tired of each other. A girl like you can always get a job. If you are worried about being dependent you can pose for me and design my frocks, and oversee Julienne”—her maid-of-all-work—”I’m sure she’s a stupendous robber.”

Amy came, not at all overwhelmed by the good luck of it—good luck was around the corner more or less for everyone, she supposed. Moreover, she was beginning to absorb some of Zora’s doctrine—she, too, must look out for herself. Zora was lonely, she did need companionship; Julienne was careless about change and odd blouses and left-over dainties. Amy had her own sense of honor. She carried out faithfully her share of the bargain, cut down waste, renovated Zora’s clothes, posed for her, listened to her endlessly and bore with her fitfulness. Zora was truly grateful for this last. She was temperamental but Amy had good nerves and her strong natural inclination to let people do as they wanted stood her in good stead. She was a little stolid, a little unfeeling under her lovely exterior. Her looks at this time belied her—her perfect ivory-pink face, her deep luminous eyes,—very brown they were with purple depths that made one think of pansies—her charming, rather wide mouth, her whole face set in a frame of very soft, very live, brown hair which grew in wisps and tendrils and curls and waves back from her smooth, young forehead. All this made one look for softness and ingenuousness. The ingenuousness was there, but not the softness—except of her fresh, vibrant loveliness.

On the whole then she progressed famously with Zora. Sometimes the latter’s callousness shocked her, as when they would go strolling through the streets south of Washing Square. The children, the people all foreign, all dirty, often very artistic, always immensely human, disgusted Zora except for “local color”—she really could reproduce them wonderfully. But she almost hated them for being what they were.

“Br-r-r, dirty little brats!” she would say to Amy. “Don’t let them touch me.” She was frequently amazed at her protégée’s utter indifference to their appearance, for Amy herself was the pink of daintiness. They were turning from MacDougall into Bleecker Street one day and Amy had patted a child—dirty, but lovely—on the head.

“They are all people just like anybody else, just like you and me, Zora,” she said in answer to her friend’s protest.

“You are the true democrat,” Zora returned with a shrug. But Amy did not understand her.

Not the least of Amy’s services was to come between and the too pressing attention of the men who thronged about her.

“Oh, go and talk to Amy,” Zora would say, standing slim and gorgeous in some wonderful evening gown. She was extraordinarily attractive creature, very white and pink, with great ropes of dazzling gold hair, and that look of no-age which only American women possess. As a matter of fact she was thirty-nine, immensely sophisticated and selfish, even Amy thought, a little cruel. Her present mode of living just suited her; she could not stand any condition that bound her, anything at all exigeant. It was useless for anyone to try to influence her. If she did not want to talk, she would not.

The men used to obey her orders and seek Amy sulkily at first, but afterwards with considerably more interest. She was so lovely to look at. But they really, as Zora knew, preferred to talk to the older woman, for while with Zora indifference was a role, second nature by now but still a role—with Amy it was natural and she was also trifle shallow. She had the admiration she craved, she was comfortable, she asked no more. Moreover she thought the men, with the exception of Stuart James Wynne, rather uninteresting—they were faddists for the most part, crazy not about art or music, but merely about some phase such s cubism or syncopation.

Wynne, who was much older than the other half-dozen men who weekly paid Zora homage—impressed her by his suggestion of power. He was a retired broker, immensely wealthy (Zora, who had known him since childhood, informed her), very set and purposeful and very polished. He was perhaps fifty-five, widely traveled, of medium height, very white skin and clear frosty blue eyes, with sharp, proud features. He liked Amy from the beginning, her childishness touched him. In particular he admired her pliability—not knowing it was really indifference. He had been married twice; one wife had divorced him, the other had died. Both marriages were unsuccessful owing to his dominant, rather unsympathetic nature. But he had softened considerably with years, though he still had decided views, was glad to see that Amy, in spite of Zora’s influence, neither smoked nor drank. He liked her shallowness—she fascinated him.

III

From the very beginning he was different form what she had supposed. To start with he was far, far wealthier, and he had, too, a tradition, a family-pride which to Amy was inexplicable. Still more inexplicably he had a race-pride. To his wife this was not only strange but foolish. She was as Zora had once suggested, the true democrat. Not that she preferred the company of her maids, though the reason for this did not lie per se in the fact that they were maids. There was simply no common ground. But she was uniformly kind, a trait which had she been older would have irritated her husband. As it was, he saw in it only an additional indication of her freshness, her lack of worldliness which seemed to him the attributes of an inherent refinement and goodness untouched by experience.

He, himself, was intolerant of all people of inferior birth or standing and looked with contempt on foreigners, except the French and English. All the rest were variously “guinerys,” “niggers,” and “wops,” and all of them he genuinely despised and hated, and talked of them with the huge intolerant carelessness characteristic of occidental civilization. Amy was never able to understand it. People were always first and last, just people to her. Growing up as the average colored American girl does grow up, surrounded by types of every hue, color and facial configuration she had had no absolute ideal. She was not even aware that there was one. Wynne, who in his grim way had a keen sense of humor, used to be vastly amused at the artlessness with which she let him know that she did not consider him good-looking. She never wanted him to wear anything but dark blue, or somber mixtures always.

“They take away from that awful whiteness of your skin,” she used to tell him, “and deepen the blue of your eyes.”

In the main she made no attempt to understand him, as indeed she made no attempt to understand anything. The result, of course, was that such ideas as seeped into her mind stayed there, took growth and later bore fruit. But just at this period she was like a well-cared for, sleek, house-pet, delicately nurtured, velvety, content to let her days pass by. She thought almost nothing of her art just now, except as her sensibilities were jarred by an occasional disharmony. Likewise, even to herself, she never criticized Wynne, except when some act or attitude of his stung. She could never understand why he, so fastidious, so versed in elegance of word and speech, so careful in his surroundings, even down to the last detail of glass and napery, should take such evident pleasure in literature of a certain prurient type. He would get her to read to him, partly because he liked to be read to, mostly because he enjoyed the realism and in a slighter degree because he enjoyed seeing her shocked. Her point of view amused him.

“What funny people,” she would say naively, “to do such things.” She could not understand the liaisons and intrigues of women in the society novels, such infamy was stupid and silly. If one starved, it was conceivable that one might steal; if one were intentionally injured, one might hit back, even murder; but deliberate nastiness she could not en visage. The stories, after she had read them to him, passed out of her mind as completely as though they had never existed.

Picture the two of them spending three years together with practically no friction. To his dominance and intolerance she opposed a soft and unobtrusive indifference. What she wanted she h ad, ease, wealth , adoration, love, too, passionate and imperious, but she had never known any other kind. She was growing cleverer also, her knowledge of French was increasing, she was acquiring a knowledge of politics, of commerce and of the big social questions, for Wynne’s interests were exhaustive and she did most of his reading for him. Another woman might have yearned for a more youthful companion, but her native coldness kept her content. She did not love him, she had never really loved anybody, but little Cornelius Boldin—he had been such a n enchanting, such a darling baby, she remembered,—her heart contracted painfully when she thought as she did very of ten of his warm softness.

“He must be a big boy now,” she would think almost mater nally, wondering-once she had been so sure!-if she would ever see him again. But she was very fond of Wynne, and he was crazy over he r just as Zora had predicted. He loaded her with gifts, dresses, flowers, jewels-she amused him because none but colored stones appealed to her.

“Diamonds are so hard, so cold, and pearls are dead,” she told him.

Nothing ever came between them, but his ugliness, his hatefulness to dependents. It hurt her so, for she was naturally kind in her careless, uncomprehending way. True, she had left Mrs. Boldin without a word, but she did not guess how completely Mrs. Boldin loved her. She wo uld have been aghast had she realized how stricken her flight had left them. At twenty-two, Amy was still as good, as unspoiled, as pure as a child. Of course with all this she was too unquestioning, too selfish, too vain, but they were all faults of h er lovely, lovely flesh. Wynne’s intolerance finally got on her nerves. She used to blush for his unkindness. All the servants were colored, but she had long since ceased to think that perhaps she, too, was colored , except when he, by insult toward an employee, overt always at least implied, made her realize his contemptuous dislike and disregard for a dark skin or Negro blood .

“Stuart, how can you say such things?” she would expostulate. “You can ‘t expect a man to stand such language as that.” And Wynne would sneer, “A man—you don’t consider a nigger a man, do you? Oh, Amy, don’t be such a fool. You’ve got to keep them in their places.”

Some innate sense of the fitness of things kept her from condoling outspokenly with the servants, but they knew she was ashamed of her husband’s ways. Of course, they left—it seemed to Amy that Peter, the butler, was always getting new “help”,—but most of the upper servants stayed, for Wynne paid handsomely and although his orders were meticulous and insistent, the retinue of employees was so large that the individual’s work was light.

Most of the servants who did stay on in spite of Wynne’s occasional insults had a purpose in view. Callie, the cook, Amy found out, h ad two children at Howard University—of course she n ever came in contact wit h Wynne—the chauffeur had a crippled sister. Rose, Amy’s maid and purveyor of much outside information, was the chief support of her family. About Peter, Amy knew nothing; he was a striking, taciturn man, very competent, who had left the Wynnes’ service years before and had returned in Amy’s third year. Wynne treated him with comparative respect. But Stephen, the new valet, met with entirely different treatment. Amy’s heart yearned toward him, he was like Cornelius, with shortsighted, patient eyes, always wi llin g, a little over-eager. Amy recognized him for what he was; a boy of respectable, ambitious parentage, striving for the means for an education; naturally far above his present calling, yet willing to pass through all this as a means to an end. She questioned Rosa about him.

“Oh ,Stephen,” Rosa told her, “yes’m, he’s workin’ for fair. He’s got a brother at the Howard’s and a sister at Smith’s. Yes’m, it do seem a little hard on him, but Stephen, he say, th ey’re both goin’ to turn roun’ and help him when they get through . That blue silk h as a rip in it, Miss Amy, if you was thinkin’ of wearin’ that. Yes’m, som ehow I don’t think Steve’s very strong, kinda worries like. I guess he’s sorta nervous.”

Amy told Wynne. “He’s such a nice boy, Stuart, she pleaded, “it hurts me to have you so cross with him. Anyway don’t call him names.” She was both surprised and fightened at the feeling in her that prompted her to interfere. She had held so aloof from other people’s interests all these years.

“I am colored,” she told herself that night. “I f eel it inside of me. I must be or I couldn’t care so about Stephen. Poor boy, I suppose Cornelius is just like him. I wish Stuart would let him alone. I wonder if all white people are like that. Zora was hard, too, on unfortunate people.” She pondered over it a bit. “I wonder what Stuart would say if he knew I was colored?” She lay perfectly still, her smooth brow knitted, thinking hard. “But he loves me,” she said to herself still silently. “He’ll always love my looks,” and she fell to thinking that all the wonderful happenings in her sheltered, pampered life had come to her through her beauty. She reached out an exquisite arm, switched on a light, and picking up a hand-mirror from a dressing-table, fell to studying her face. She was right. It was her chiefest asset. She forgot Stephen and fell asleep.

But in the morning her husband’s voice issuing from his dressing-room across the hall, awakened her. She listened drowsily. Stephen, leaving the house the day before, had been met by a boy with a telegram. He had taken it, slipped it in to his pocket, (he was just going to the mail-box) and had forgotten to deliver it until now, nearly twentyfour hours later. She could hear Stuart’s storm of abuse—it was terrible, made up as it was of oaths a n d insults to the boy’s ancestry. There was a moment’s lull. Then she heard him again.

“If your brains are a f air sample of that black wench of a sister of yours— “

She sprang up then thrusting her arms as she ran into her pink dressing-gown . She got there just in time. Stephen, his face quivering, was standing looking straight in to Wynne’s smoldering eyes. In spite of herself, Amy was glad to see the boy’s bearing. But he did not notice her.

“You devil!” he was saying. “You white faced devil! I’ll make you pay for that!” He raised his arm. Wynne did not blench.

With a scream she was between them. “Go, Stephen, go,—get out of the house. Where do you think you are? Don’t you know you’ll be hanged, lynched, tortured?” Her voice shrilled at him.

Wynne tried to thrust aside her arms that clung and twisted. But she held fast till the door slammed behind the fleeing boy.

“God, let me by, Amy!” As suddenly as she had clasped him she let him go, ran to the door, fastened it and threw the key out the window.

He took her by the arm and shook her. “Are you mad? Didn’t you hear him threaten me, me,—a nigger threaten me?” His voice broke with anger, “And you’re letting him get away! Why, I’ll get him. I’ll set bloodhounds on him, I’ll have every white man in this town after him! He’ll be hanging so high by midnight—”he made for the other door, cursing, half-insane.

How, how could she keep him back! She hated her weak arms with their futile beauty! She sprang toward him. ‘Stuart, wait,” she was breathless and sobbing. She said the first thing that came into her head. Wait, Stuart, you cannot do this thing.” She thought of Cornelius—suppose it had been he—”Stephen,—that boy,—he is my brother.”

He turned on her. “What!” he said fiercely, then laughed a short laugh of disdain. “You are crazy,” he said roughly, “My God, Amy! How can you even in jest associate yourself with these people? Don’t you suppose I know a white girl when I see one? There’s no use in telling a lie like that.”

Well, there was no help for it. There was only one way. He had turned back for a moment, but she must keep him many moments—an hour. Stephen must get out of town.

She caught his arm again. “Yes,” she told him, “I did lie. Stephen is not my brother, I never saw him before.” The light of relief that crept into his eyes did not escape her, it only nerved her. “But I am colored,” she ended.

Before he could stop her she had told him all about the tall white woman. “She took me to Mrs. Boldin’s and gave me to her to keep. She would never have taken me to her if I had been white. If you lynch this boy, I’ll let the world, your world, know that your wife is a colored woman.”

He sat down like a man suddenly stricken old, his face ashen. “Tell me about it again,” he commanded. And she obeyed, going mercilessly into every damning detail.

IV

Amazingly her beatury availed her nothing. If she had been an older woman, if she had had Zora’s age and experience, she would have been able to gauge exactly her influence over Wynne. Through even then in similar circumstances she would have taken the risk and acted in just the same manner. But she was a little bewildered at her utter miscalculation. She had though he might not wasn’t his friends—his world by which he set such store—to know that she was colored, but she had not dreamed it could make any real difference to him. He had chosen her, poor and ignorant, out of a host of women, and had told her countless times of his love. To herself Amy Wynne was in comparison with Zora for instance, stupide and uninteresting. But his constant, unsolicited iterations had made her accept his idea.

She was just the same woman she told herself, she had not changed, she was still beautiful, still charming, still “different.” Perhaps that very difference had its being in the fact of her mixed blood. She had been his wife—there were memories—she could not see how he could give her up. The suddenness of the divorce carried her off her feet. Dazedly she left him—thought almost without a pang for she had only like him. She had bee perfectly honest about this, and he, although consume by the fierceness of his emotion toward her, had gradually forced himself to be content, for at least she had never made him jealous.

She was to live in a small house of his in New York, up town in the 80’s. Peter was in charge and there were a new maid and a cook. the servants, of course, knew od the separation, but nobody guess why/ She was living on a much smaller basis than the one to which she had become so accustomed in the last three years. But she was very comfortable. She felt, at any rate she manifested, no qualms at receiving alimony from Wynne. That was the way things happened, she supposed when she thought of it at all. Moreover, it seemed to her perfectly in keeping with Wynne’s former attitude toward her; she did not see how he could do less. She expected people to be consistent. That was why she was so amazed that he in spite of his oft iterated love, could let her go. If she had felt half the love for him which he had professed for her, she would not have sent him away if she had been a leper.

“Why I’d stay with him,” she told herself, “If he were one, even as I feel now.”

She was lonely in New York. Perhaps it was the first time in her life that she had felt so. Zora had gone to Paris the first of the year of her marriage and had not come back.

The days dragged on emptily. One thing helped her. She had gone one day to the modiste from whom she had bought her trousseau. The woman remembered her perfectly—”The lady with the exquisite taste for colors—ah, madame, but you have the rare gift.” Amy was grateful to be taken out of her thoughts. She bought one of two daring but altogether lovely creations and let fall a few suggestions:

“That brown frock, Madame,—you say it has been on your hands a long time? Yes? But no wonder. See, instead of that dead white you should have a shade of ivory, that white cheapens it.” Deftly she caught up a bit of ivory satin and worked out her idea. Madame was ravished.

“But yes, Madame Wen is correct,—as always. Oh, what a pity that the Madame is so wealthy. If she were only a poor girl—Mlle. Antoine with the best eye for color in the place has just left, gone back to France to nurse her brother—this World War is of such horror! If someone like Madame, now, could be found, to take the little Antoine’s place!”

Some obscure impulse drove Amy to accept the half proposal: “Oh! I don’t know, I have nothing to do just now. My husband is abroad.” Wynne had left her with that impression. “I could contribute the money to the Red Cross or to charity.”

The work was the best thing in the world for her. It kept her from becoming too introspective, though even then she did more serious, connected thinking than she had done in all the years of her varied life.

She missed Wynne definitely, chiefly as a guiding influence for she had rarely planned even her own amusements. Her dependence on him had been absolute. She used to picture him to herself as he was before the trouble—and his changing expressions as he looked at her, of amusement, interest, pride, a certain little teasing quality that used to come into his eyes, which always made her adopt her “spoiled child air,” as he used to call it. It was the way he liked her best. Then last, there was that look he had given her the morning she had told him she was colored—it had depicted so many emotions, various and yet distinct. There were dismay, disbelief, coldness, a final aloofness.

There was another expression, too, that she thought of sometimes—the look on the face of Mr. Packard, Wynne’s lawyer. She, herself, had attempted no defense.

“For God’s sake why did you tell him, Mrs. Wynne?” Packard asked her. His curiosity got the better of him. “You couldn’t have been in love with that yellow rascal,” he blurted out. “She’s too cold really, to love anybody,” he told himself. “If you didn’t care about the boy why should you have told?”

She defended herself feebly. “He looked so like little Cornelius Boldin,” she replied vaguely, “and he couldn’t help being colored.” A clerk came in then and Packard said no mare. But into his eyes had crept a certain reluctant respect. She remembered the look, but could not define it.

She was so sorry about the trouble now, she wished it had never happened. Still if she had it to repeat she would act in the same way again. “There was nothing else for me to do,” she used to tell herself.

But she missed Wynne unbelievably.

If it had not been for Peter, he life would have been almost that of a nun. But Peter, who read the papers and kept abreast of the times, constantly called her attention with all due respect, to the meetings, the plays, the sights which she ought to attend or see. She was truly grateful to him. She was very kind to all three of the servants. They had the easiest “places” in New York, the maids used to tell their friends. As she never entertained, and frequently dined out, they had a great deal of time off.

She had been separated from Wynne for ten months before she began to make any definite plans for her future. Of course, she could not go on like this always. It came to her suddenly that probably she would go to Paris and live there—why or how she did not know. Only Zora was there and lately she had begun to think that her life was to be like Zora’s. They had been amazingly parallel up to this time. Of course she would have to wait until after the war.

She sat musing about it one day in the big sitting-room which she had had fitted over into a luxurious studio. There was a sewing-room off to the side from which Peter used to wheel into the room waxen figures of all colorings and contours so hat she could drape the various fabrics about them to be sure of the bext results. But today she was working out a scheme for one of Madame’s customers, who was of her own color and size and she was her own lay-figure. She sat in front of the huge pier glass, a wonderful soft yellow silk draped about her radiant loveliness.

“I could do some serious work in Paris,” she said half aloud to herself. “I suppose if I really wanted to, I could be very successful along this line.”

Somewhere downstairs and electric bell buzzed, at first softly then after a slight pause, louder, and more insistently.

“If Madame send me that lace today,” she was thinking, idly, “I could finish this and start on the pink. I wonder why Peter doesn’t answer the bell.”

She remembered then that Peter had gone to New Rochelle on business and she had sent Ellen to Altman’s to find a certain rare velvet and had allowed Mary to go with her. She would dine out, she told them, so they need not hurry. Evidently she was alone in the house.

Well she could answer the bell. She had done it often enough in the old days at Mrs. Boldin’s. Of course it was the lace. She smiled a bit as she went down stairs thinking how surprised the delivery-boy would be to see her arrayed thus early in the afternoon. She hoped he wouldn’t go. She could see him through the long, thick panels of glass in the vestibule and front door. He was just turning about as she opened the door.

This was no delivery-boy, this man whose gaze fell on her hungry and avid. This was Wynne. She stood for a second leaning against the door-lamb, a strange figure surely in the sharp November weather/ Some leaves—brown, skeleton shapes—rose and swirled unnoticed about her head. A passing letter-carrier looked at them curiously.

“What are you doing answering the door?” Wynne asked her roughly. “Where is Peter? Go in, you’ll catch cold.”

She was glad to see him. She took him into the drawing room—a wonderful study in browns—and looked at him and looked at him.

“Well,” he asked her, his voice eager in spite of the commonplace words, “are you glad to see me? Tell me what do you do with yourself.”

She could not talk fast enough, her eyes clinging to his face. Once it struck her that he had changed in some indefinable way. Was it a slight coarsening of that refined aristocratic aspect? Even in her sub-consciousness she denied it.

He had come back to her.

“So I design for Madame when I feel like it, and send the money to the Red Cross and wonder when you are coming back to me.” For the first time in their acquaintanceship she was conscious deliberately of trying to attract, to hold him. She put on her spoiled child air which had once been so successful.

“It took you long enough to get here,” she pouted. She was certain of him now. His mere presence assured her.

They sat silent a moment, the later November sun bathing her head in an austere glow of chilly gold. As she sat there in the big brown chair she was, in her yellow dress, like some mysterious emanation, some wraith-like aura developed from the tone of her surroundings.

He rose and came toward her, still silent. She grew nervous, and talked incessantly with sudden unusual gestures. “Oh, Stuart, let me give you tea. It’s right there in the pantry off the dining-room. I can wheel the table in.” She rose, a lovely creature in her yellow robe. He watched her intently.

“Wait,” he bade her.

She paused almost on tiptoe, a dainty golden butterfly.

“You are coming back to live with me?” he asked her hoarsely.

For the first time in her life she loved him.

“Of course I am coming back,” she told him softly. “Aren’t you glad? Haven’t you missed me? I didn’t see how you could stay away. Oh! Stuart, what a wonderful ring!”

For he had slipped on her finger a heavy dull gold band, with an immense sapphire in an oval setting—a beautiful thing of Italian workmanship.

“It is so like you to remember,” she told him gratefully. “I love colored stones.” She admired it, turning it around and around on her slender finger.

How silent he was, standing there watching her with his somber yet eager gaze. It made her troubled, uneasy. She cast about for something to say.

“You can’t think how I’ve improved since I saw you, Stuart. I’ve read all sorts of books—Oh! I’m learned,” she smiled at him. “And Stuart,” she went a little closer to him, twisting the button on his perfect coat, “I’m so sorry about it all,—about Stephen, that boy you know. I just couldn’t help interfering. But when we’re married again, if you’ll just remember how it hurts me to have you so cross—”

He interrupted her. “I wasn’t aware that I spoke of our marrying again,” he told her, his voice steady, his blue eyes cold.

She thought he was teasing. “Why you just asked me to. You said ‘aren’t you coming back to live with me—’”

“Yes,” he acquiesced, “I said just that—‘to live with me’.”

Still she didn’t comprehend. “But what do you mean?” she asked bewildered.

“What do you suppose a man means,” he returned deliberately, “when he asks a woman to live with him, but not to marry him?”

She sat down heavily in the brown chair, all glowing ivory and yellow against its somber depths.

“Like the women in those awful novels?” she whispered. “Not like those women!—Oh Stuart! you don’t mean it!” Her heart was numb.

“But you must care a little—” she was amazed at her own depth of feeling. “Why I care—there are all those me memories back of us—you must want me really—”

“I do want you,” he told her tensely. “I want you damnably. But—well—I might as well out with it—A white man like me simply doesn’t marry a colored woman. After all what difference need it make to you? We’ll live abroad—you’ll travel, have all the things you love. Many a white woman would envy you.” He stretched out an eager hand.

She evaded it, holding herself aloof as though his touch were contaminating. Her movement angered him.

Like a rending veil suddenly the veneer of his high polish cracked and the man stood revealed.

“Oh, hell!” he snarled at her roughly. “Why don’t you stop posing? What do you think you are anyway? Do you suppose I’d take you for my wife—what do you think can happen to you? What man of your own race could give you what you want? You don’t suppose I am going to support you this way forever, do you? The court imposed no alimony. You’ve got to come to it sooner or later—you’re bound to fall to some white man. What’s the matter—I’m not rich enough?”

Her face flamed at that—”As though it were that that mattered!”

He gave her a deadly look. “Well, isn’t it? Ah, my girl, you forget you told me you didn’t love me when you married me. You sold yourself to me then. Haven’t I reason to suppose you are waiting for a higher bidder?”

At these words something in her died forever, her youth, her happy, happy blindness. She saw life leering mercilessly in her face. It seemed to her that she would give all her future to stamp out, to kill the contempt in his frosty insolent eyes. In a sudden rush of savagery she struck him, struck him across his hateful sneering mouth with the hand which wore his ring.

As she fell, reeling under the fearful impact of his brutal but involuntary blow, her mind caught at, registered two things. A little thin stream of blood was trickling across his chin. She had cut him with the ring, she realized with a certain savage satisfaction. And there was something else which she must remember, which she would remember if only she could fight her way out of this dreadful clinging blackness, which was bearing down upon her—closing her in.

When she came to she sat up holding her bruised, aching head in her palms, trying to recall what it was that had impressed her so.

Oh, yes, her very mind ached with the realization. She lay back again on the floor, prone, anything to relieve that intolerable pain. But her memory, her thoughts went on.

“Nigger,” he had called her as she fell, “nigger, nigger,” and again, “nigger.”

“He despised me absolutely,” she said to herself wonderingly, “Because I was colored. And yet he wanted me.”

V

Somehow she reached her room. Long after the servants had come in, she lay face downward across her bed, thinking. How she hated Wynne, how she hated herself! And for ten months she had been living off his money although in no way had she a claim on him. Her whole body burned with the shame of it.

In the morning she rang for Peter. She faced him, white and haggard, but if the man noticed her condition, he made no sign. He was, if possible, more impertur bable than ever.

“Peter,” she told him, her eyes and voice very steady, “I am leaving this house today and shall never come back.”

“Yes, Miss.”

“I shall wan t you to see to the packing and storing of the goods and to send the keys and the receipts for the jewelry and valuables to Mr. Packard in Baltimore.”

“Yes, Miss.”

“And, Peter, I am very poor now and shall have no money besides what I can make for myself.”

“Yes, Miss.”

Would nothing surprise him, she wondered dully. She went on “I don’t know whether you knew it or not, Peter, but I am colored, and hereafter I mean to live among my own people. Do you think you could find me a little house or a little cottage not too far from New York?”

He had a little place in New Rochelle, he told her, his manner altering not one whit, or better yet his sister had a four room house in Orange, with a garden, if he remembered correctly. Yes, he was sure there was a garden. It would be just the thing for Mrs. Wynne.

She had four hundred dollars of her very own which she had earned by designing f or Madame. She paid the maids a month in advance-they were to stay as long as Peter needed them. She, herself, went to a small hotel in Twenty-eighth Street, and here Peter came for her at the end of ten days, with the acknowledgement of the keys and receipts from Mr. Packard. Then he accompanied her to Orange and installed her in her new home.

“I wish I could afford to keep you, Peter ,” she said a little wistfully, “but I am very poor. I am heavily in debt and I must get that off my shoulders at once.”

Mrs. Wynne was very kind, he was sure; he could think of no one with whom he would prefer to work. Furthermore, he of ten ran down from New Rochelle to see his sister; he would come in from time to time, and in the spring would plant the garden if she wished.

She hated to see him go, but she did not dwell long on that. Her only thought was to work and work and work and save until she could pay Wynne back. She had not lived very extravagantly during those ten months and Peter was a perfect manager—in spite of her remonstrances he had given her every month an account of his expenses. She had made arrangements with Madame to be her regular designer.The French woman guessing that more than whim was behind this move drove a very shrewd bargain, but even then the pay was excellent. With care, she told herself, she could be free within two years, three at most.

She lived a dull enough existence now, going to work steadily every morning and getting home late at night. Almost it was like those early days when she had first left Mrs. Boldin, except that now she had no high sense of ad venture, no expectation of great things to come, which might buoy her up. She no longer thought of phases and the proper setting f or her beauty. Once indeed catching sight of her face late one night in the mirror in her tiny work-room in Orange, she stopped and scanned herself, loathing what she saw there.

“You thing!” she said to the image in t he glass, “if you hadn’t been so vain, so shallow!” And she had struck herself violently again and again across the f ace until her head ached.

But such fits of passion were rare. She had a curious sense of freedom in these days, a feeling that at last her brain, her senses were liberated from some hateful clinging thralldom. Her thoughts were always busy. She used to go over that last scene wit h Wynne again and again trying to probe the inscrutable mystery which she felt was at the bottom of the affair. She groped her way toward a solution, but always something stopped her. Her impulse to strike, she realized, and his brutal rejoinder had been actuated by something more than mere sex antagonism, there was race antagonism there—two elements clashing. That much she could fathom. But that he despising her, hating her for not being white should yet desire her! It seemed to her that his attitude toward her—hate and yet desire, was the attitude in microcosm of the whole white world toward her own, toward that world to which those few possible strains of black blood so tenuously and yet so tenaeciously linked her.

Once she got hold of a big thought. Perhaps there was some root, some racial distinction woven in with the stuff of which she was formed which made her persistently kind and unexacting. And perhaps in the same way this difference, helplessly, inevitably operated in making Wynne and his kind, cruel or at best indifferent. Her reading for Wynne reacted to her thought—she remembered the grating insolence of white exploiters in foreign lands, the wrecking of African villages, the destruction of homes in Tasmania. She couldn’t imagine where Tasmania was, but wherever it was, it had been the realest thing in the world to its crude inhabitants.

Gradually she reached a decision. There were two divisions of people in the world—on the one hand insatiable desire for power; keenness, mentality; a vast and cruel pride. On the other there was ambition, it is true, but modified, a certain humble sweetness, too much inclination to trust, an unthinking, unswerving loyalty. All the advantages in the world accrued to the first division. But without bitterness she chose the second. She wanted to be colored, she hoped she was colored. She wished even that she did not have to take advantage of her appearance to earn her living. But that was to meet an end. After all she had contracted her debt with a white man, she would pay him with a white man’s money.

The years slipped by— four of them. One day a letter came from Mr. Packard. Mrs. Wynne had sent him the last penny of the sum received from Mr. Wynne f rom February to November, 1914. Mr. Wynne had refused to touch the money, it was and would be indefinitely at Mrs. Wynne’s disposal.

She never even answered the letter. Instead she dismissed the whole incident,—Wynne and all,—from her mind and began to plan for her future. She was free, free ! She had paid back her sorry debt with labor, money and anguish. From now on she could do as she pleased. Almost she caught herself saying “something is going to hap pen.” But she checked herself, she hated her old attitude.

But something was happening. Insensibly from the moment she knew of her deliverance, her thoughts turned back to a stifled hidden longing, which had lain, it seemed to her, an eternity in her heart. Those days with Mrs. Boldin! At night,—on her way to New York,—in the workrooms,—her mind was busy with little intimate pictures of that happy, wholesome, unpretentious life. She could see Mrs. Boldin, clean and portly, in a lilac chambray dress, upbraiding her for some trifling, yet exasperating fault. And Mr. Boldin, immaculate and slender, with h is noticeably polished air—how kind he had always been, she remembered. And lastly, Cornelius; Cornelius in a thousand attitudes and engaged in a thousand occupations, brown and near-sighted and sweet—devoted to his pretty sister, as he used to call her; Cornelius, who used to come to her as a baby as willingly as to his mother; Cornelius spelling out colored letters on his blocks, pointing to them stickily with a brown, perfect finger; Cornelius singing like an angel in his breathy, sexless voice and later murdering everything possible on his terrible cornet. How had she ever been able to leave them all and the dear shabbiness of that home! Nothing, she realized, in all these years had touched her inmost being, had penetrated to the ·core of her cold heart like the memories of those early, misty scenes.

One day she wrote a letter to Mrs. Boldin. She, the writer, Madame A. Wynne, had come across a young woman, Amy Kildare, who said that as a girl she had run away from home and now she would like to come back. But she was ashamed to write. Madame Wynne had questioned the girl closely and she was quite sure that this Miss Kildare had in no way incurred shame or disgrace. It had been some time since Madame Wynne had seen the girl but if Mrs. Boldin wished, she would try to find her again—perhaps Mrs. Boldin would like to get in touch with her. The letter ended on a tentative note.

The answer came at once.

My dear Madame Wynne:

My mother told me to write you this letter. She says even if Amy Kildare had done something terrible, she would want her to come home again. My father says so too. My mother says, please find her as soon as you can and tell her to come back. She still misses her. We all miss her. I was a little boy when she left, but though I am in the High School now and play in the school orchestra, I would rather see her than do anything I know. If you see her, be sure to tell her to come right away. My mother says thank you.

Yours respectfully,

CORNELIUS BOLDIN.

The letter came to the modiste’s establishment in New York. Amy read it and went with it to Madame. “I have had wonderfu l news,” she told her, “I must go away immediately, I can’t come back—you may have these last two weeks f or nothing.” Madame, who h ad surmised long since the separation, looked curiously at the girl’s flushed cheeks, and decided that “Monsieur Ween” had returned. She gave her fatalistic shrug. All Americans were crazy.

“But, yes, Madame,—if you must go—absolument.”

When she reached the ferry, Amy looked about her searchingly. “I hope I’m seeing you for the last time—I’m going home, home!” Oh, the unbelievable kindness! She had left them without a word and they still wanted her back!

Eventually she got to Orange and to the little house. She sent a message to Peter’s sister and set about her packing. But first she sat down in the little house and looked about her. She would go home, home—how she loved the word, she would stay there a while, but always there was life, still beckoning. It would beckon forever she realized to her adventurousness. Afterwards she would set up an establishment of her own,—she reviewed possibilities—in a rich suburb, where white women would pay and pay for her expertness, caring nothing f or realities, only for externals.

“As I myself used to care,” she sighed. Her thoughts flashed on. “Then some d ay I’ll work and help with colored people—the only ones who have really cared for and wanted me.” Her eyes blurred.

She would never make any attempt to find out who or what she was. If she were white, there would always be people urging her to keep up the silliness of racial prestige. How she hated it all!

“Citizen of the world, that’s what I’ll be. And now I’ll go home.”

Peter’s sister’s little girl came over to be with the pretty lady whom she adored. “You sit here, Angel, and watch me pack,” Amy said, placing her in a little arm-chair. And the baby sat there in silent observation, one tiny leg crossed over the other, surely the quaintest, gravest bit of bronze, Amy thought, that ever lived.

“Miss Amy cried,” the child told her mot he r afterwards.

Perhaps Amy did cry, but if so she was unaware. Certainly she laughed more happily, more spontaneously than she had done for years. Once she got down on her knees in front of the little arm-chair and buried her face in the baby’s tiny bosom.

“Oh Angel, Angel,” she whispered, “do you suppose Cornelius still plays on that cornet?”

Reading and Review Questions

- The story opens with Amy in a dressmaker’s shop trying on a new and expensive gown. What does the story’s fascination with costume suggest about Amy’s racial identity?

- How does Fauset’s treatment of Amy’s “awakening” compare to the presentation of race in the work of Nella Larsen and Zora Neale Hurston?

- Compare and contrast Amy’s relationships with other women in the story.