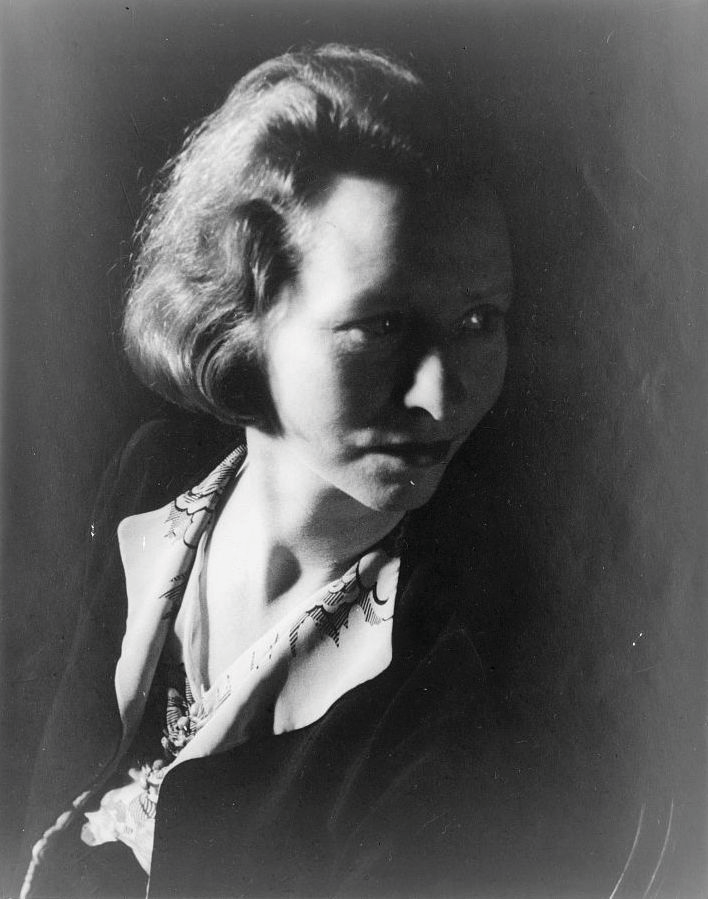

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950)

Edna St. Vincent Millay, 1933

Photographer | Carl Van Vechten

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

When the first of our selections from Edna St. Vincent Millay, “First Fig,” was published in Poetry in October 1918, the twenty-six year old author was already a published poet and a rising figure in the Greenwich Village literary scene. Yet “First Fig,” and the four other lyrics that appeared alongside it in that issue, are notable because they demonstrate—in a total of just twenty lines—both Millay’s mastery of the lyric form and her determined frankness. In this way, Millay represents both a continuation of poetic traditions and a new approach to appropriate subject matter for women’s poetry. Like many female poets of the early part of the twentieth century, Millay appears at once to straddle two worlds: on one hand her poetry shows great technical skill, which permits her entry into the ranks of so-called serious poets, while on the other hand, her verses show a lightness, a frankness, and a freshness from which a poet like Dickinson would retreat. For Millay and other female poets, as for their African-American contemporaries like Countee Cullen, it was often necessary to embrace traditional poetic forms even as their subject matter was decidedly modern.

One of three daughters of a divorced mother at the turn of the century, Millay’s early successes resulted in the unusual opportunity to attend Vassar College in her early twenties, and these social and educational connections proved highly useful to the young writer. A gifted playwright as well as a poet, Millay was a member of the experimental theatre group, the Provincetown Players, for whom she frequently wrote while also composing several books of poetry. As a sometime expatriate in the 1920s, Millay liberally combined traditional poetic forms and contemporary subjects in her verse, prose, and drama. The winner of the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1923, for The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver, Millay was both a critically and a commercially successful writer.

“First Fig,” the opening lyric in a group known as Figs from Thistles, is familiar to many readers who encountered it in high school, where it is often included as a tool for teaching about scansion and prosody. Composed of just four lines that alternate between iambic pentameter and iambic tetrameter, and featuring a strong end-rhyme, “First Fig” is often a gateway work in modernist poetry because it mimics forms with which readers are already comfortable. Yet the poem quickly challenges our expectations by celebrating excess: “My candle burns at both ends,” for example, and then acknowledging the speaker’s foes as readily as the speaker’s friends. These elements combined with the exclamatory, “It gives a lovely light!” in the last line transport the imagery from the usual one of decay into a celebration. This celebration of rapid change unites “First Fig” with the other four lyrics with which it was first published into a celebration of the present.

The second selection from Millay, “I Think I Should Have Loved You Presently” (1922), provides additional evidence of the poet’s technical skills. A sonnet in the Shakespearean tradition, “I Think I Should Have Loved You Presently,” uses the occasion of an absent lover not as a moment for regret but as an occasion to acknowledge the impermanence of romantic love. In the first few lines, the speaker makes clear that it was a choice, and not mere caprice that caused her to act as she did in jesting with a recent lover. Despite the loss of her lover’s affections, the speaker would not change her ways, instead choosing to “Cherish no less the certain stakes I gained” (11) than to regret her dalliance. For these and other epigrammatic lines, Millay remains one of the most quoted modernist poets.

“First Fig”

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

“I Think I should Have loved You Presently”

I think I should have loved you presently,

And given in earnest words I flung in jest;

And lifted honest eyes for you to see,

And caught your hand against my cheek and breast;

And all my pretty follies flung aside

That won you to me, and beneath your gaze,

Naked of reticence and shorn of pride,

Spread like a chart my little wicked ways.

I, that had been to you, had you remained,

But one more waking from a recurrent dream,

Cherish no less the certain stakes I gained,

And walk your memory’s halls, austere, supreme,

A ghost in marble of a girl you knew

Who would have loved you in a day or two.

Reading and Review Questions

- How does Millay’s choice of the sonnet form distinguish her work from that of other Modernists such as Eliot, Moore, Stevens, and Williams? Also, why do writers like Cullen and Millay experiment with the sonnet form?

- Millay is one of the first American poets to write candidly about female sexuality. How does Millay’s poetry reflect the attitudes of Modernism in relation to female sexuality?