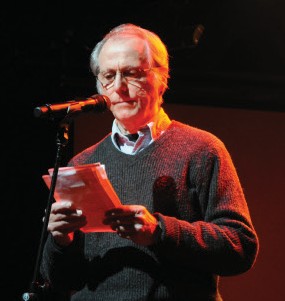

Don Delillo (1936 – )

Don Delillo, 2011

Photographer | User “Thousand Robots”

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY-SA 2.0

In the sixteen darkly satiric novels he has published to date, Don DeLillo shows us how disorienting, mysterious and absurd life in postmodern America can be. DeLillo was born in Brooklyn, New York, and graduated from Fordham University in the Bronx. While DeLillo is known for his careful research and erudition, he admits that “I never liked school” in a rare 2000 interview in the South Atlantic Quarterly. Instead, he explains that he received his education primarily from New York City itself, in particular from the city’s intense avant-garde artistic culture on display in its modern art museums, jazz clubs, and art cinemas. After college, DeLillo stayed in the city to work for an advertising agency, quitting in 1964 after five years to pursue a career as a writer. Since then he has published in venues ranging from The Kenyon Review and The New Yorker to Rolling Stone and Sports Illustrated and has won dozens of awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, the National Book Award for Fiction, and the PEN/ Faulkner Award. DeLillo’s capacious work centers around a wide cast of familiar American characters, from football players, rock stars, writers, and child prodigies to college professors, spies, stock brokers, and the real-world assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald—all of whom live in an America that is saturated with media, obsessed with violent entertainment, prone to conspiracy, overloaded with sensation, overcrowded with the detritus of militarism and capitalism, and poised on the brink of apocalypse. To represent the superabundance of contemporary American culture—from the lives we live to those we mythologize to those we know only through movies and TV—DeLillo has worked in numerous narrative forms, including the sports novel (End Zone 1972 and Amazons 1980), the rock and role satire (Great Jones Street 1972), science fiction (Ratner’s Star 1976), the thriller (Players 1977, Running Dog 1978, and The Names 1982), the weighty modernist odyssey (Cosmopolis 2003), the dense postmodernist historical novel (Underworld 1997, Libra 1988, and Mao II 1991), and even closely observed American realism (Falling Man 2007).

DeLillo’s academic satire White Noise, a selection of which is included here, received the National Book Award for Fiction in 1985. White Noise represents what everyday American life is like for “men and women who live,” as DeLillo describes in a 1993 Paris Review interview, “in the particular skin of the late twentieth century.” White Noise holds an estranging mirror to 1980s Cold War American culture, foregrounding the absurdity behind much everyday American behavior. The novel is narrated by Jake Gladney—a professor of an invented academic field called “Hitler Studies”—who is so disconnected from the real Adolph Hitler that he doesn’t even know German and does not study the Holocaust. A four-time divorcee, Jake lives in a house full of the children from his past marriages and his present wife, a woman addicted to a drug that cures her fear of death. DeLillo uses the misadventures of Professor Gladney to explore themes ranging from consumerism, non-traditional families, addiction, and medicalization to conspiracies, mass destruction, the relation of media to reality, and the mystery of life itself. In the brief section included here, Jake has accompanied his colleague Murray Jay Siskind (a professor who wants to create a new academic field modeled on Hitler Studies called “Elvis Presley Studies”) to “The Most Photographed Barn in America.” The visit to this piece of Americana then becomes an occasion for DeLillo’s characters to converse about what it means to live in America today.

“The Most Photographed Barn in America” (excerpt from White Noise)

Please click the link below to access this selection:

http://text-relations.blogspot.com/2011/03/most-photographed-barn-in-america.html

Reading and Review Questions

-

- “No one sees the barn,” Murray observes. Why does no one see the barn?

- In his influential essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” the cultural theorist Walter Benjamin argues that photographs and films strip their original objects of the “aura” of authenticity by removing them from the traditions and situations of which they are organically a part. One cannot photograph the entire material history of a work of art, after all. Murray argues that “every photograph” taken of the barn actually “reinforces the aura” it possesses. If photographs strip things of their aura of authenticity then how can this be? Describe the aura these pictures reinforce. What is unique or artistic about this barn, if anything? What do we see when we look within the barn’s much-photographed aura?