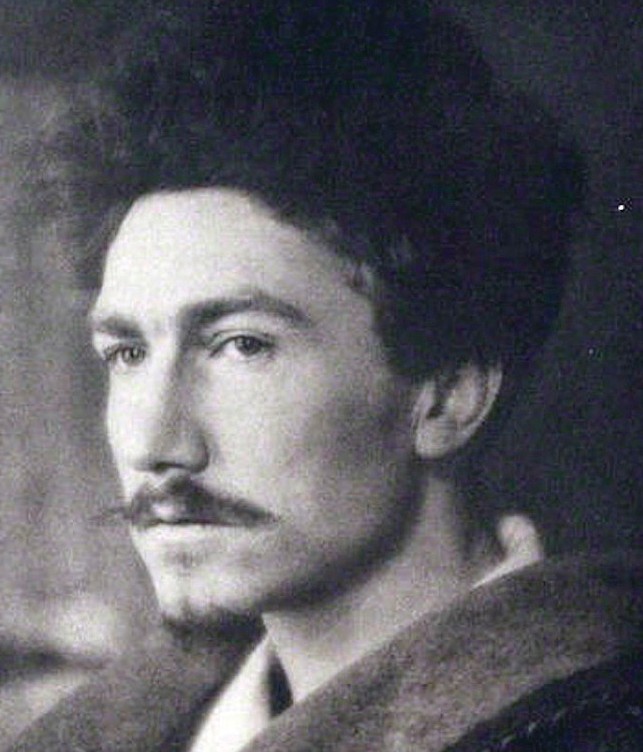

Ezra Pound (1885-1972)

Ezra Pound, 1913

Photographer | Alvin Langdon Coburn

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

As brilliant as he was controversial, Ezra Pound more than any other single poet or editor shaped modernist poetry into the forms you find in this chapter. Pound grew up in Philadelphia and attended the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied world languages and became friends with fellow poets Hilda Doolittle (H. D.) and William Carlos Williams. After being fired from his first college teaching job at Wabash College for his idiosyncratic behavior, Pound moved to London in 1908, working as a teacher, book reviewer, and secretary to William Butler Yeats. The energetic and prolific Pound soon became a force within London’s literary scene, urging his fellow poets to break from poetic tradition and, as he famously wrote, “make it new.” Over his lifetime Pound published collections of critical essays such as “Make it New” (1934) and The ABC of Reading (1934), translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry, and volumes of his own poetry, most notably his 116 Cantos, a decades-long project that he envisioned as the sum total of his life’s learnings and observations. After the World War I, Pound became disillusioned with free-market democratic society, blaming it for both the immediate war and the general decline of civilization. He moved to Italy and became enamored with Italy’s fascist government, recording hundreds of pro-fascist radio programs for Rome Radio that were broadcast to allied troops. After the war, Pound was arrested for treason, found mentally unfit, and incarcerated in Washington, D.C.’s Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital until 1958, when his fellow poets successfully lobbied to have him freed.

Pound influenced modernist literature in two ways: by championing and editing numerous writers such as H. D., Robert Frost, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Wyndham Lewis, and T. S. Eliot (whose The Waste Land he substantially revised); and by campaigning for the Imagist and Vorticist poetic movements. “In a Station of the Metro” is a perfect example of an Imagist poem. The poem is based on an experience Pound had of stepping off a train in Paris’s underground Metro. As he writes in his essay, “From Vorticism,” he “saw suddenly a beautiful face, and then another and another…and I tried all that day to find words for what this had meant to me…” It took Pound an entire year to find those words. His first draft of the poem was thirty lines long. His second draft was fifteen lines long. Still unable to express the emotion he felt that day, Pound continued to cut verbiage from the poem until it came closer in form to a Japanese haiku than a traditional Western lyric. The final two-line poem exemplifies Pound’s three criteria for an Imagist poem: that the poet must treat things directly; eliminate unnecessary words; and use rhythm musically, not mechanically.

“In a Station of the Metro”

The apparition of these faces in the crowd:

Petals on a wet, black bough.

Reading and Review Questions

- Consider the title as part of the poem. How does the title set your expectations for what follows?

- Explore the word “apparition” in the poem’s first line. What meanings and associations does this one word evoke?

- What emotions does the imagery of petals and water in the poem’s second line convey?