Chapter 1: Introduction to Geography

1.6 Regions at Different Scales

1.6.1 Types of Regions in the Cultural Landscape

A region’s distinct identity is shaped by its cultural landscape, which encompasses a blend of cultural elements such as language and religion, economic aspects like agriculture and industry, and physical characteristics including climate and vegetation. For instance, Northern Virginia can be clearly distinguished from the Tidewater region due to these varying cultural, economic, and physical attributes.

The world can be divided into regions based on human and/or physical characteristics. Regions simply refer to spatial areas that share a common feature. There are three types of regions: formal, functional, and vernacular.

Source: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

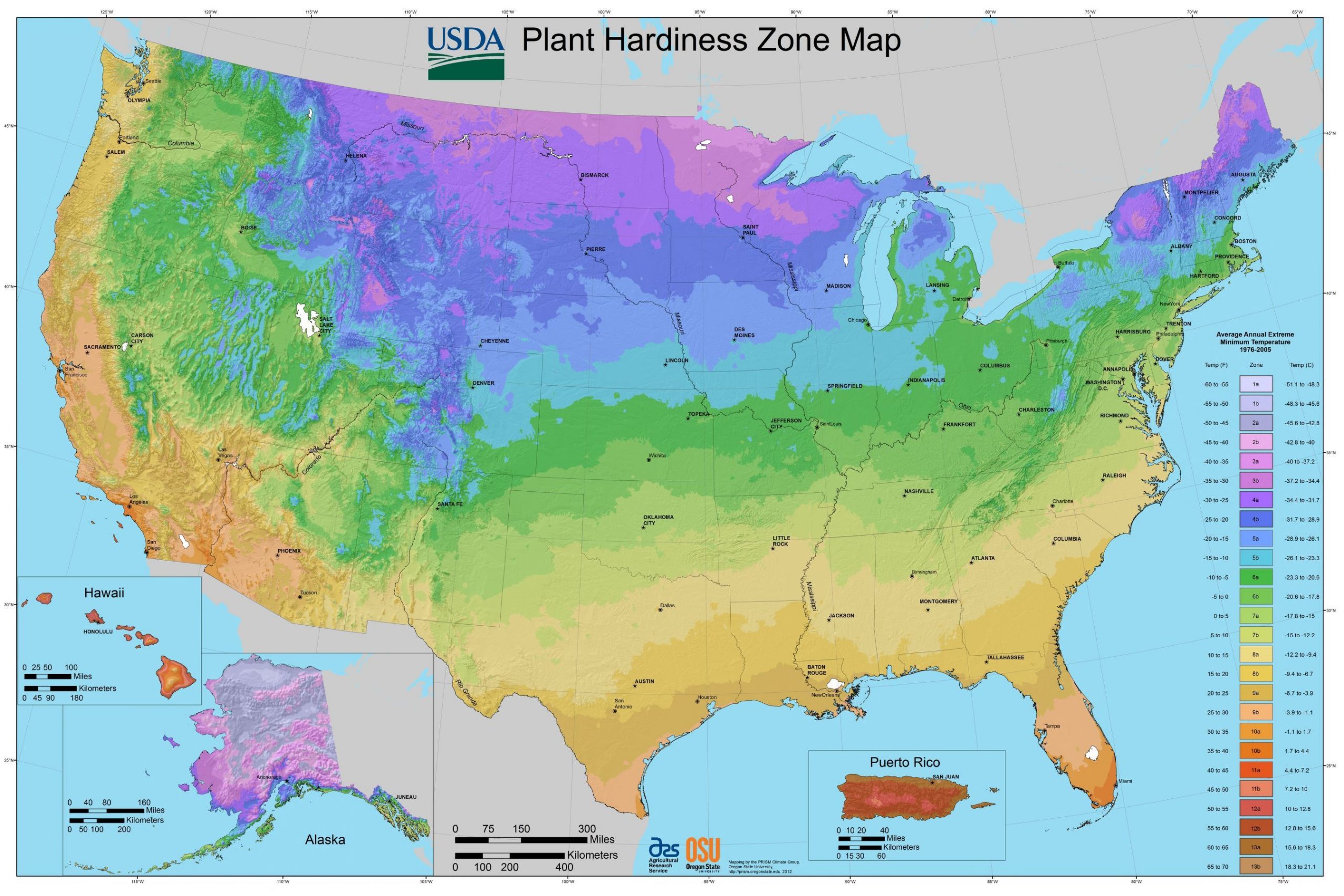

Formal regions have at least one characteristic in common. A map of plant hardiness regions, as in Figure 1.6.1, for example, divides the United States into regions based on average extreme temperatures, showing which areas particular plants will grow well. This isn’t to say that everywhere within a particular region will have the same temperature on a particular day, but rather that in general, a region experiences the same ranges of temperature. Other formal regions might include religious or political affiliation, agricultural crop zones, or ethnicity. Formal regions might also be established by governmental organizations, such as the case with state or provincial boundaries.

Source: “Europe religion map situation 1950 en.png” by San Jose via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Functional regions, unlike formal regions, are not homogenous in the sense that they do not share a single cultural or physical characteristic. Rather, functional regions are united by a particular function, often economic. Functional regions are sometimes called nodal regions and have a nodal arrangement, with a core and surrounding nodes. A metropolitan area, for example, often includes a central city and its surrounding suburbs. We tend to think of the area as a “region” not because everyone is the same religion or ethnicity, or has the same political affiliation, but because it functions as a region. Washington DC, for example, is the a city not even reaching 1 million people (~671,000 people). However, the region of the Greater Washington area extends far beyond its official city limits as show in Figure 1.6.3.

Source: “Population density by census tract in the DC metro area in 2010 and 2020” retrieved from Greater Greater Washington is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

In 2019, approximately 779,000 residents of the Washington metropolitan area reported D.C. as their workplace. By 2021, this number had decreased to 561,600, likely because many of the commuters chose to work remotely. Washington, as with all metropolitan areas, functions economically as a single region and is thus considered a functional region. Other examples of functional regions include church parishes, radio station listening areas, and newspaper subscription areas.

While the three major inner-suburban areas—Fairfax County, Montgomery County, and Prince George’s County—grew at a slower pace (13.0%) compared to the overall region, the core urban areas experienced slightly higher growth rates: Arlington County grew by 14.9%, the District of Columbia by 14.6%, and Alexandria by 13.9%. However, the most significant growth occurred in the outer suburban and exurban areas near the region’s edge-particularly along Route 7 and Interstate 95-reflecting a broader national trend of population growth driven primarily by exurban sprawl. Other examples of functional regions include church parishes, radio station listening areas, and newspaper subscription areas.

Source: “Map of the Southern United States modern definition.png” by Astrokey44 via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

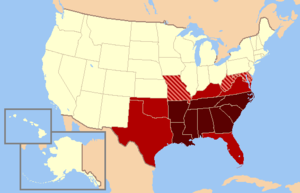

Vernacular regions are those that exist in people’s minds.] Vernacular regions are not as well-defined as formal or functional regions and are based on people’s perceptions. The southeastern region of the United States is often referred to as “the South,” but where the exact boundary of this region is depends on individual perception (see Figure 1.6.4). Some people might include all of the states that formed the Confederacy during the Civil War. Others might exclude Missouri or Oklahoma; include or exclude Texas or parts of Florida.

Vernacular regions exist at a variety of scales. In your hometown, there might be a vernacular region called “the west side.” Such “west sides’ tended to be the wealthier areas as they were upwind from the prevailing west winds.

Source: “Greater Middle-East (orthographic projection).svg” by Hogweard via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Internationally, regions like the Midlands in Britain or the Swiss Alps are considered vernacular. Similarly “the Middle East” is a vernacular region. It is perceived to exist as a result of religious and ethnic characteristics, but people wouldn’t necessarily agree on which countries to include. Vernacular regions are real in the sense that our perceptions are real, but their boundaries are not uniformly agreed upon.

As geographers, we can divide the world into a number of different regions based upon formal criteria and functional interaction. However, there is a matter of perception, as well. We might divide the world based on landmasses, since landmasses often share physical and cultural characteristics. Sometimes water connects people more than land, though. In the case of Europe, for example, the Mediterranean Sea historically provided economic and cultural links to the surrounding countries though we consider them to be three separate continents. Creating regions can often be a question of “lumpers and splitters;” who do you lump together and who do you split apart? Do you have fewer regions united by only a couple characteristics, or more regions that share a great deal in common?

1.6.2 Global Regions

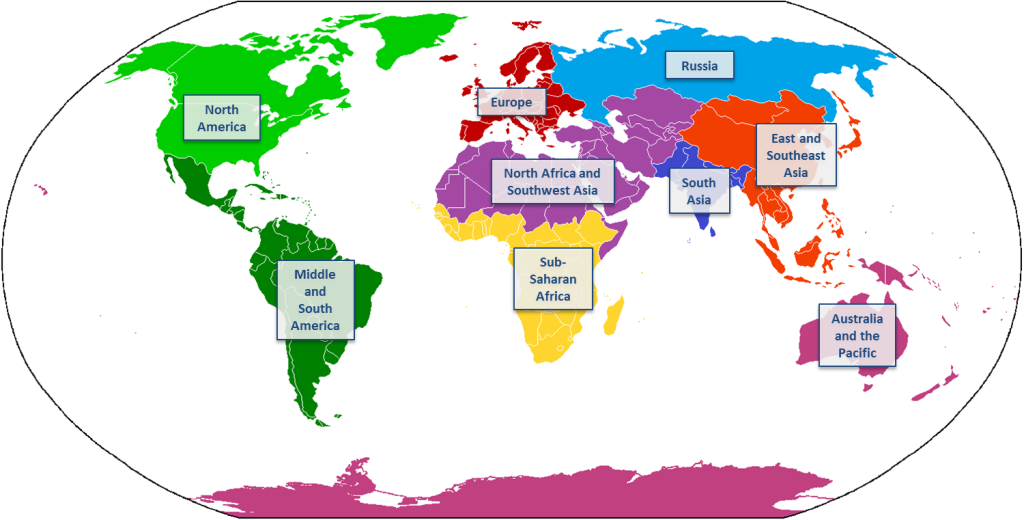

Textbooks on regional geography often explore certain regions of the world such as ‘Europe’ or ‘North America”. Figure 1.6.6 is an attempt at splitting the world up into several regions, however, these regions are largely vernacular. Where does “Middle” America end and “South” America begin, and why is it combined into a single region? Why is Pakistan, a predominantly Muslim country, characterized as “South” Asia and not “Southwest” Asia? Why is Russia its own region? You might divide the world into entirely different regions, maybe seven based on the continents, or just two: the “core” and the “periphery.” These nine regions are not universally agreed-upon; they are simply foundations for discussing the different areas of the world.

Source: “Map of World Regions” by Caitlin Finlayson is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. The image was adapted from “Continents vide couleurs 2.png” by Cogito ergo sumo via Wikimedia Commons.

Furthermore, while it might seem like there are clear boundaries between the world’s regions, in actuality, where two regions meet are zones of gradual transition. These transition zones are marked by gradual spatial change. Moscow, Russia, for example, is quite similar to other areas of Eastern Europe, though they are considered two different regions on the map. The ongoing war in Ukraine and President Putin claiming eastern Ukraine as Russian is testament to the area being a transition zone.Were it not for the Rio Grande and a large border fence dividing the cities of El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, you might not realize that this metropolitan area stretches across two countries and world regions. Even within regions, country borders often mark spaces of gradual transition rather than a stark delineation between two completely different spaces. The border between Peru and Ecuador, for example, is quite relaxed as international borders go and residents of the countries can move freely across the boundary to the towns on either side (see Figure 1.6.7).

Source: “Aguas Verdes, Peru.jpg” by Vanished_user_j123kmqwfk56jd via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

1.6.3 From the Global to Local Scale

Scale refers to the relationship between the area of Earth being studied and the Earth as a whole. Geographers are particularly interested in the contrasts between the local scale and the global scale, especially in the context of globalization. Globalization is a process that involves the entire world and results in making something worldwide in scope.

Globalization means that the scale of the world is shrinking in terms of the ability of a person, object, or idea to interact with another person, object, or idea in a different place. Simultaneously, geographers acknowledge the growing importance of the local scale, where groups of people are preserving and reviving distinctive cultural characteristics and implementing unique economic practices to counteract globalization impacts.

Scale and Cultural Change

Scale plays a crucial role in understanding cultural change, particularly in how global and local influences shape each other. As globalization progresses, uniform cultural preferences have emerged, leading to the creation of consistent global landscapes characterized by similar material artifacts and cultural values. This phenomenon reflects a convergence where diverse cultures begin to exhibit common traits, driven by the widespread exchange of ideas, products, and media.

One prominent example is the proliferation of global fast-food chains like McDonald’s and Starbucks. These brands, initially rooted in American culture, have become ubiquitous across the world, creating a uniform landscape of food consumption and dining experiences. Despite regional adaptations, such as local menu items or store designs, the core elements of these chains—standardized menus, logos, and service styles—contribute to a globally recognizable dining experience. This uniformity reflects a broader trend where local variations are increasingly influenced by global cultural norms and commercial practices.

Another example is the global impact of popular music and entertainment. Music genres such as pop and hip-hop have transcended their origins, becoming dominant across various cultures and regions. Artists from different countries often incorporate elements of these global genres into their work, creating a shared cultural experience. The widespread appeal of international music festivals and streaming platforms further illustrates how global cultural products shape local tastes and preferences, contributing to a more uniform cultural landscape.

However, while globalization fosters cultural homogenization, it also prompts local responses and adaptations. In many cases, communities strive to preserve their unique cultural identities amidst global influences. For instance, traditional festivals, languages, and artisanal crafts are actively maintained and promoted as a form of resistance to cultural erosion. These efforts highlight the ongoing tension between global uniformity and local distinctiveness, where cultural change is continually negotiated at different scales.

The concept of scale is fundamental in understanding economic change, particularly as it relates to the dynamics between local, national, and global economies. Economic activities are increasingly interconnected, and the scale at which these activities operate can significantly influence economic outcomes and transformations. Globalization, driven by technological advances and international trade, has led to the integration of markets and economies across the world, creating a complex web of economic interactions.

Scale and economic change

At a global scale, multinational corporations have become dominant players in the world economy, shaping economic practices and influencing local markets. For example, companies like Apple and Amazon operate on a global scale, with production, distribution, and sales spanning multiple countries. Their economic activities affect local economies by influencing labor markets, driving innovation, and setting global standards for consumer products. This global reach allows these corporations to leverage economies of scale, reducing costs and increasing efficiency, but it can also lead to local economic shifts, such as job displacement or changes in local business practices.

Conversely, local economies are also impacted by global economic trends, and local responses can drive economic change. For instance, the rise of global tourism has significantly affected local economies in popular destinations. Cities and regions that attract international tourists often experience economic growth through increased spending in hospitality, retail, and service sectors. However, this influx can also lead to economic challenges, such as rising property prices and the displacement of local residents. Local governments and businesses must navigate these changes by balancing economic benefits with sustainable development and community needs.

Economic change also manifests at the national scale, where policies and economic strategies are developed to respond to global trends. Countries may adopt policies to attract foreign investment, foster technological innovation, or protect local industries from global competition. For example, China’s rapid economic growth over the past few decades has been driven by its integration into the global economy, coupled with strategic national policies aimed at boosting manufacturing and technology sectors. This economic transformation at the national level demonstrates how countries adapt to and shape global economic forces, influencing their development trajectories and global economic standing.

Overall, the interplay between different scales—global, national, and local—highlights the dynamic nature of economic change. Understanding these interactions helps in grasping how economic policies, global market trends, and local responses collectively shape economic outcomes and drive transformation across different levels.