Chapter 9: Political Organization of Space

9.2 Theories in Political Geography

9.2.1 Power and Politics

One common misconception people have about geography is that it’s all about states and capitals. Geographers certainly do care about place, but memorizing a list of states and capitals is not at all what geographers do, nor how geography is taught, particularly in a world where this information is much more readily accessible than times past due to technology.

Political geography is a subfield of human geography that examines how politics influences place and how place and its distinctiveness shapes the kind of politics that operate there. Geographers always have an eye open towards noticing and evaluating the spatial distribution of phenomenon and possible resulting unevenness. In the case of political geography, this translates to examining how political structures are distributed across the world, understanding the context of why political structures operate where they do, and the impact this has on peoples’ everyday lives and the global world order, or how power is distributed internationally.

Politics is first and foremost about power.

Check out the video below to learn about two key types of power: hard power which operates by force and coercion and soft power which operates by fostering consent and attraction.

Politics can be understood in three senses:

- High Politics: essential to state survival (examples: elections, war and peace, diplomacy)

- Low Politics: non-essential to state survival; mundane; about welfare of the state (examples: department of education, environmental protection agency)

- politics with a lower case p: challenging existing structures of power (examples: Black Lives Matter movement, gun right’s advocacy groups)

Political geography examines how all three aspects of politics intersect in place and impact peoples’ livelihoods.

9.2.2 Theoretical Concepts

Political geography is the study of the ways in which humans have divided up the surface of the Earth for purposes of management and control. Looking beyond the patterns on political maps helps us to understand the spatial outcomes of political processes and the ways in which political processes are themselves affected by spatial features. Political spaces exist at multiple scales, from a kid’s bedroom to the entire planet; i.e. from very local to global levels. At each location, somebody or some group seeks to establish the rules governing what happens in that space, how power is shared (or not) and who even has the right to access those spaces. This is also known as territoriality.

Many people have tried to exert control over the physical world to exert power for religious, economic or cultural reasons (sometimes all three!). A few names you might recognize are Alexander the Great, Queen Victoria, Napoleon Bonaparte and Adolf Hitler. Scholars have developed many theories of how political power has been expressed geographically as leaders and nations vie to control people, land, and resources. In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s scholars developed many theories about how political power is expressed geographically. These theories have been used to both justify and work to avoid conflict.

Organic Theory by Friedrich Ratzel, 1897

This theory states that nations must continually seek nourishment in the form of gaining land to survive in the same way that a living organism seeks nourishment from food to survive. As a result, it implies that if a nation does not seek out and conquer new territories, it will risk failing because other nations also behave in an organic way. This is akin to the law of the jungle – eat or be eaten.

Hitler was a proponent of organic theory and used Raztel’s term Lebensraum or “living space” as justification for Germany’s behavior during World War II. He claimed that if Germany didn’t grow in this way, it would fall victim again to the rest of the Europe and eventually the world as it did during the First World War.

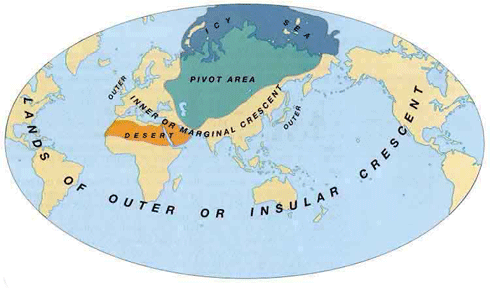

Heartland Theory by Sir Halford Mackinder, 1904

Also known as “The Geographic Pivot of History” theory, Mackinder thought that whoever controlled Eastern Europe – the Heartland – would control the world. The idea is that the Heartland is a pivot point for controlling all of Asia and Africa, which he referred to as the World Island. Why was the Heartland so important at this time? Eastern Europe is abundant in raw materials and farmland which are needed to support a large army who could then control the coasts and water ports that make international trade possible. Both Hitler and the USSR believed this was possible, but both failed because they did not foresee the rise of other world powers such as the United States and China. Nor did they know that military technology would soon advance far beyond tanks and ground troops to include nuclear weapons, high-tech missiles, and drone airplanes.

Rimland Theory by Nicholas John Spykman, 1942

Source: “Map Geopolitic Mackinder” by Arnopeters via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

According to Spykman, Mackinder’s “lands of the outer rim” were the key to controlling Eurasia and then the world. He theorized that because the Rimland contains most of the world’s people as well as a large share of world’s resources it was more important than Heartland. The Rimland’s defining characteristic is that it is an intermediate region, lying between the heartland and the marginal sea powers. As the amphibious buffer zone between the land powers and sea powers, it must defend itself from both sides, and therein lies its fundamental security problems.

Politically, Spykman called for the consolidation of the Rimland countries to ensure their survival during World War II. With the defeat of Germany and the emergence of the USSR, Spykman’s views were embraced during the formulation of the Cold War American policy to containing communist influence.

While the Rimland theory focuses on strategic geopolitical zones and their importance in global politics, the world-systems theory discussed next focuses on economic relationships and hierarchies between core, periphery, and semi-periphery countries.

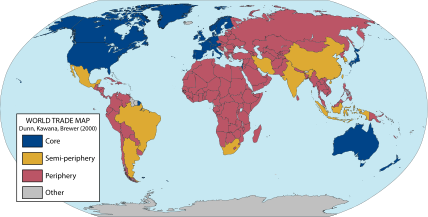

World Systems Theory by Wallerstein, 1974

Source: “World trade map” by Vladusty via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC0 1.0.

World-systems theory offers a framework for understanding the hierarchical relationships between different regions and countries. At its core, this theory posits that the world economy is characterized by a hierarchical structure composed of three interconnected zones: core, periphery, and semi-periphery.

The core countries represent the economically dominant and technologically advanced nations, typically with diversified economies and strong infrastructure. These countries exert significant influence over global trade, finance, and production networks. They often benefit from high levels of industrialization, innovation, and capital accumulation. Examples include countries like the United States, Germany, and Japan.

Conversely, the periphery comprises countries and regions that are economically marginalized, often reliant on exporting raw materials and agricultural products. These nations have limited industrialization and infrastructure development, resulting in economic dependence on the core countries. They frequently experience lower standards of living, higher levels of poverty, and limited access to education and healthcare. Examples include many countries in Africa, parts of Latin America, and parts of Asia.

The semi-periphery occupies an intermediate position between the core and periphery. These countries exhibit characteristics of both core and periphery nations. They may have developed industrial sectors and significant economic growth but still face challenges such as income inequality, political instability, and dependence on core countries for technology and investment.

9.2.3 Colonialism and Resultant Power Disparities

According to Wallerstein, the emergence of a global economy commenced with the mercantilist practices of early modern European states. Mercantilism laid the groundwork for the ascent of an increasingly expansive capitalist economic system that encompassed the entire world by 1900. Capitalism denotes a system wherein individuals, corporations, and states possess land and produce goods and services for exchange with the aim of generating profit. In pursuit of profit, producers seek cost-effective production methods. For instance, when labor costs (including wages and benefits) became the priciest aspect of production, companies relocated manufacturing operations from North Carolina to Mexico, and subsequently to China and Southeast Asia, to capitalize on lower labor costs.

In addition to leveraging the global labor pool, producers profit by commodifying whatever they can. Commodification involves assigning a monetary value to goods, services, or ideas and engaging in their trade. Companies innovate new products, introduce variations of existing ones, and stimulate demand through marketing. As children, neither author of this book could have conceived of purchasing bottled water. Now, bottled water sales are commonplace.

World-systems theory helps us understand how colonial powers amassed and maintained significant concentrations of wealth. Initially, European colonizers extracted resources from the Americas, the Caribbean, and Africa, employing slave labor to cultivate commodities like sugar, coffee, fruit, and cotton. Meanwhile, Russia expanded through territorial conquests over land, while the United States pursued similar expansionist policies in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. After the Industrial Revolution, European powers targeted industrial labor, raw materials, and large-scale agricultural plantations across Africa, Southeast Asia, and beyond, fostering a more interconnected global economy. Even nations like China and Iran, which were never formally colonized, were coerced into signing unequal treaties granting concessions to European powers. Following European models, Japan developed its own colonial empire, extending control over Korea, parts of East and Southeast Asia, and numerous Pacific islands until its defeat in World War II.

Source: “Descolonización – Decolonization” by Universalis via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

This historical process resulted in a global system marked by profound power disparities between core and periphery nations. Notably, not all current core countries were colonial powers; countries such as Switzerland, Singapore, and Australia wield substantial global influence despite never engaging in traditional colonialism. Their influence stems from strategic relationships with colonial powers or their adeptness in navigating a global economy dominated by core nations. They attained core status by integrating into networks of production, consumption, and trade in the wealthiest regions of the world, capitalizing on their access to these networks.

Thus, world-systems theory provides insights into how colonial powers reshaped global political structures. Following the end of colonialism in Africa and Asia, newly independent states adopted the European model of state organization. Colonial borders, drawn arbitrarily during the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 (usually straight lines meaning geometric boundaries), became the boundaries of these newly sovereign nations. Former colonial territories transitioned into independent states, with colonial administrative centers often serving as their capitals. One of the primary political hurdles for African states post-independence has been forging cohesive, stable nations from highly diverse and sometimes conflicting ethnic groups.