Chapter 4: Interpreting Place and Cultural Landscape

4.2 What is a Cultural Landscape?

By chance, have you ever heard of the word “palimpsest”? I’m going to guess the answer is no, but this unique sounding word is helpful in understanding what cultural landscapes are, how they are formed, and how to interpret or produce meaning from them, all of which are the topics of this chapter.

Let’s take a closer look.

According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, a palimpsest is “writing material (such as a parchment or tablet) used one or more times after earlier writing has been erased” and “something having usually diverse layers or aspects apparent beneath the surface.”

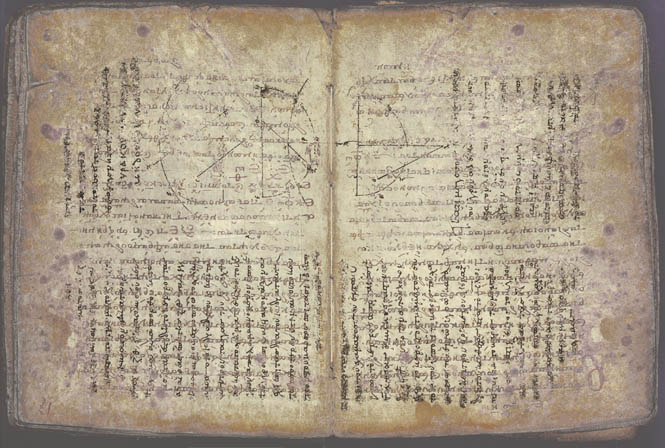

Below is a photograph of a prayer book, with traces of what was previously written on the parchment pages, which were mathematical notes by Greek mathematician Archimedes.

Source: “Archimedes Palimpsest” by Matthew Kon via Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain in the United States. Click the image to see it on Wikimedia Commons.

Before paper, books were made up of pages of parchment, which was typically made from animal skin and was scarce and pricey. This meant that instead of discarding an out-of-use book, the original text would be scraped off the parchment and new text would be layered on. The trace of what came before was figuratively palpable and literally present. You can see this on the page above.

Landscapes are like palimpsests: they bear the trace of what came before and frame what comes next.

Landscapes are accumulations of the past–both natural and human-made past influences, spanning from the recent past to the distant past. Like books, they can be read or interpreted. Instead of words on the page signifying the meaning, natural and human-made forces and elements that have shaped the landscape signify the landscape’s meaning. Cultural landscapes specifically examine how human systems and forces shape landscape more so than natural forces.

A landscape encompasses more than just a scenic view from a lookout point; it refers to an area of land that holds a socially-created unity due to the behaviors and meanings people associate with it. Cultural activities leave traces on the landscape, intentionally or unintentionally, which future cultural activities must navigate. Landscapes often serve a conservative function, as they are constructed to facilitate a particular way of life, thereby encouraging its continuation while making alternative lifestyles more challenging.

Source: “The View of Phoenix’s Urban Sprawl from 4000 Ft. South Mountain in Background , 6 1972” by Cornelius Michael via Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain.

For example, the Phoenix, Arizona metro area was designed for a car-centric culture, featuring wide roads often without sidewalks, extensive parking lots, and a sprawling layout of homes and businesses. Someone moving to Phoenix from a place like New York City or Paris where walking and public transportation are more common, will find it difficult to maintain those habits. Conversely, a Phoenix resident accustomed to car-based living will struggle to adapt to the densely packed, narrow streets of New York City or Paris.

4.2.1 Dysfunctional Landscapes / Landscape Elements

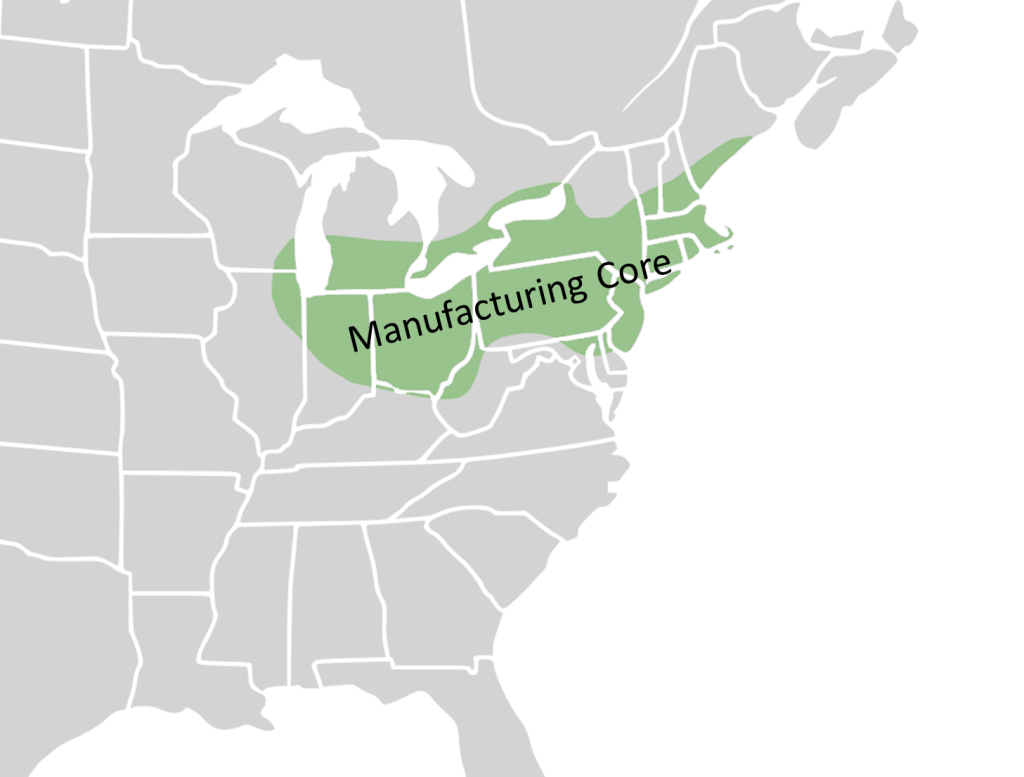

Source: “Figure 4.8: Map of the North American Manufacturing Core Region (Derivative work from original by Lokal Profil, Wikimedia Commons)” by Caitlin Finlayson via World Regional Geography is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

Source: “Map of Emerging US Megaregions” by IrvingPlNYC is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Tensions can arise when cultural demands are misaligned with the constructed landscape, leading to struggles to reshape it. For economic activity to thrive, infrastructure such as roads, houses, and factories must be built. However, as profit opportunities shift over time, this existing infrastructure can become a burden. The “rust belt” in the northeast and Great Lakes region of the United States exemplifies this. From the mid-1800s to mid-1900s, this region thrived due to factors like cheap labor and transportation access, making it ideal for industries like automobiles and steel forming the famous “Manufacturing Belt”. . The towns and cities that developed around these factories involved substantial investments in both infrastructure and culture, as places like Detroit or Worcester became “home” and fostered social networks. However, as the dominant manufacturing belt industries, such as steel and automotive manufacturing, faced intense international competition and decreased demand starting in the mid-20th century and thus relocated to the “sun belt” in the southern US for cheaper, non-unionized labor or abroad, the area became less profitable and turned into the “rust belt”. While this relocation offered long-term benefits for companies and opportunities for sun belt residents, it was disastrous for those in the rust belt. The mass exodus of jobs led to significant population loss as workers moved away in search of employment. This, in turn, caused urban decay, with abandoned buildings, deteriorating infrastructure, and reduced municipal tax revenues making it difficult for cities to maintain services and attract new businesses.They now face the choice between abandoning their cultural landscape or finding new creative ways to repurpose a landscape deeply marked by industrialism’s legacy.

On a smaller scale, one can observe the phenomenon of abandoned malls in urban areas and strip malls scattered across the landscape. Attitudes towards these shopping centers have shifted, partly due to the rise of online shopping and partly because people have less time to drive to and stroll through malls. In some areas, there are efforts to revitalize these once-thriving retail hubs.

In the case of brownfields—properties where redevelopment or reuse is complicated by the presence of hazardous materials, pollution, or contaminants—significant effort is required. Check this story map by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality.

Petroleum can contaminate groundwater, the source of drinking water for nearly half of the U.S. population. Petroleum brownfields, such as old, abandoned gas stations, are being cleaned up and reused to the benefit of communities across the country. Many of the old gas stations in Virginia (and elsewhere) joined this effort: for example, the Art of Coffee in Montross offers gourmet coffee and breakfast in an art gallery showcasing co-owner Holly Harman’s original watercolors. In Petersburg,; the Bistro at Market and Grove features a menu including honey-glazed duck and shrimp crostini; and on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, the Machipongo Trading Company boasts as “The Eastern Shore’s finest coffee and gourmet snack shop,” serves wraps, burritos, and paninis. Also, in Charlottesville Ivy Provisions presents tea and coffee specials alongside fresh, local menu items available for breakfast, lunch, and dinner alongside Fry’s Spring Station, which boasts a 22-pie brick oven for crafting fresh pizzas. Meanwhile, Jake’s Place in Ashland offers pulled pork, fried green tomatoes, and pimento cheese sandwiches.

4.2.2 Landscape as Symbol

In addition to imposing practical constraints on cultural activity, landscapes can also embody meaning, known as symbolic landscapes (Meinig 1979). Sometimes, this meaning is directly inscribed on the landscape through monuments. For example, the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, two giant Buddha statues carved in the 500s CE, honored the local Buddhist religion and served as a site for religious ceremonies. In 2001, the Taliban, Afghanistan’s ruling Islamic fundamentalist group, destroyed the Buddhas. For the Taliban, the statues not only represented a false religion but also violated a specific commandment in some interpretations of Islam against human depictions. After the Taliban’s fall in 2003 following the US invasion, various donors from Afghanistan and around the world expressed interest in rebuilding the Buddhas. With the Taliban currently in control of the country, such revitalization efforts are indefinitely postponed.

Another example of a symbolic landscape is the National Mall in Washington, D.C. This expansive area, stretching from the Capitol to the Lincoln Memorial, is more than just a public space; it embodies the ideals and history of the United States. The monuments and memorials within the Mall, such as the Washington Monument, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, and the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, each carry profound significance. They commemorate pivotal figures and events in American history, symbolizing the nation’s struggles, achievements, and ongoing aspirations for freedom, equality, and justice.

The interpretation of the National Mall extends beyond its physical presence. It is a place where Americans and visitors from around the world come to reflect on the country’s democratic principles and historical milestones. The Mall also serves as a gathering site for protests, celebrations, and public discourse, reinforcing its role as a living symbol of democracy and civic engagement. The presence of these monuments in a shared public space underscores the collective memory and identity of the nation, continuously shaping and being shaped by the evolving narrative of American history.

Source: “Houses in Sterling Park” by Ser Amantio di Nicolao via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal.

But meaning is not solely confined to intentional monumental architecture. Consider Figure 4. depicting a typical US suburb characterized by detached single-family homes surrounded by grassy yards along a tranquil residential street. This everyday landscape serves as a potent symbol of the American ideal, embodying the “American dream” of homeownership with a spouse and 2.3 children. It’s worth noting that this layout facilitates living out this dream but makes it challenging to adopt alternative cultural practices, such as large extended families residing together under one roof or life for empty nesters as these houses may be too large. This suburban setting symbolizes the essence of the United States as effectively as more overtly symbolic landscapes like the Capitol in Washington, DC (see above), or the presidential portraits on Mount Rushmore. Hence, such landscapes are extensively employed as symbols, often in advertisements seeking to link their products with wholesome, conventional American life.

Source: “Inner City Street Scene Camden – New Jersey” by Adam Jones, Ph.D. via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Conversely, some landscapes may symbolize negative aspects. The “inner city,” depicted in Figure 3, holds significant symbolic weight in mainstream US perception. It underscores what are commonly viewed as the primary societal challenges — crime, drug use, fractured families, and poverty — all associated with a specific place inhabited by particular demographics. However, it’s crucial to recognize that the symbolic significance of these landscapes may not align with the lived experiences of their residents. While the suburban ideal may represent alienation and discrimination for some individuals, such as gays and lesbians (Valentine 1993), the inner city can harbor functional social systems and provide sanctuary from discrimination in the broader society.

The symbolic value of a given landscape may be contested between different groups if they feel strongly about the use of a certain landscape. Take, for example, the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff, Arizona. For the US Forest Service and its contractors who operate a ski lodge there, the peaks represent the beauty of nature and the prospect of outdoor recreation. On the other hand, for local Native American tribes like the Hopi and Navajo, the peaks represent a sacred source of life-giving water (Glowacka et al. 2009). Each of these groups would like to use and modify the landscape in accordance with the meaning it bestows on it. Thus, the Native Americans would like to limit most human interference while maintaining the trails they use to visit sites on the peaks where religious ceremonies are carried out. The Forest Service, on the other hand, wants to expand the ski area by using reclaimed wastewater for snow-making. The incompatibility of these two versions of the cultural landscape led to a lawsuit in which the federal 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ultimately upheld the Forest Service’s right to expand the ski area (Navajo Nation v. US Forest Service 2008).

4.2.3 Toponyms

Symbolic landscapes are often reinforced through the use of place names, also known as toponyms (see Chapter 6 on Language for more information).. The name given to a place not only reflects the significance attributed to it by the namer but also influences how subsequent generations perceive the place. For instance, Pittsburgh was named after the British statesman William Pitt, the city of Charleston, South Carolina named after King Charles II of England, Louisville, Kentucky in honor of the French king.

In Australia, the nickname “Oz” conjures a laid-back yet enchanting image of the country because The word Australia when referred to informally with its first three letters becomes Aus. When Aus or Aussie, the short form for an Australian, is pronounced for fun with a hissing sound at the end, it sounds as though the word being pronounced has the spelling Oz. On the other hand, New Zealanders honor indigenous culture by using “Aotearoa,” the native Maori name for their land.

Figure 4.2.7 St. Petersburg in Russia from Google Maps

The impact of toponyms becomes particularly evident when place names undergo changes. For example, the Russian city of St. Petersburg was initially named to honor Tsar Peter the Great, who aimed to integrate Russia more closely with Western Europe. In 1914, amidst anti-German sentiment, the city’s name was changed to “Petrograd” , “grad” being Russian and meaning “city”. During the Soviet era, it was further renamed “Leningrad” to reflect communist ideals and honor Vladimir Lenin. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the city reverted to its original name, “St. Petersburg,” as part of a broader initiative to remove Lenin’s legacy, including statues and place names, from the Russian landscape.

4.2.4 Cultural Traits and Diffusion

Cultural landscapes often contain a record of successive waves of cultural diffusion (see the Chapter on Cultural Patterns). Diffusion can take many forms. In some cases, diffusion is caused by the movement of people. Immigrants to a new place bring with them the cultures they obtained from their original home country. Diffusion may also occur without the movement of people. It is common for people in one society to take up cultural traits they learned from another.

As a cultural trait spreads, it undergoes inevitable adaptations to fit into its new cultural context, necessitating adjustments to both the trait itself and the receiving culture. Therefore, to comprehend the diffusion of a cultural trait, it is essential to study the processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization.

When a cultural trait spreads, it undergoes adaptation to fit its new cultural context, and this adjustment requires reciprocal changes in the receiving culture. Therefore, to comprehend the diffusion of a cultural trait, it is essential to study processes like deterritorialization and reterritorialization (Androutsopoulos and Scholz 2003). Deterritorialization involves isolating a specific trait or group of traits from its original cultural system, defining its boundaries, and preparing it for transfer. Reterritorialization, on the other hand, integrates the trait into its new environment, often necessitating modifications to align with other cultural traits of the destination. For instance, even a globally standardized product like a McDonald’s hamburger undergoes adjustments: in India, where religious dietary rules prohibit beef consumption, veggie burgers are offered, while in Australia, the “McOz” features a slice of pickled beet, reflecting local preferences for beet in sandwiches.