Chapter 8: The Geography of Religion

8.6 Religion and Conflict

8.6.1 Religion and Social Change

Religion and social change are deeply interconnected, with each influencing the other significantly. Fundamentalism and communism represent two distinct ideological approaches to societal transformation. Religion often provides moral and ethical frameworks that guide human behavior and societal norms, inspiring movements for social justice and equity. However, fundamentalism advocates for a strict adherence to traditional religious doctrines, often opposing modernity and secularism. This approach can enforce traditional values and norms, sometimes leading to societal tension, especially in diverse or secular societies where pluralism and modern values prevail.

Conversely, communism seeks to create a classless, stateless society through collective ownership of production means and the abolition of private property. Viewing religion as a tool for maintaining social control, many communist regimes promote secularism and scientific rationalism, often suppressing religious practices. This ideological clash frequently results in conflict, as fundamentalist groups resist the atheistic and secular principles of communism, while communist regimes see religious movements as threats to their vision of social equality and unity. The interaction between these ideologies continues to shape global politics and social dynamics profoundly.

India: Hinduism and Social Equality

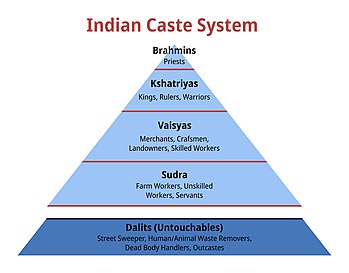

Source: “Indian Caste System” by Giveaway285 via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Hinduism, one of the world’s oldest religions, has historically been associated with the caste system, a social stratification structure that divides people into distinct groups. This system classifies individuals into four main castes: Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (traders and merchants), and Shudras (laborers and service providers). Beyond these, there is a group traditionally considered outside the caste system, known as the Dalits or “untouchables.” Over the centuries, the original castes split into thousands of subcastes. The caste system dictates various aspects of life, including occupation, dietary habits, and social interactions, often leading to significant social and economic inequalities. Until very recently, social interactions such as enjoying a meal together or marriage were limited and the rights of non-Brahmans were quite restricted. The rigid caste system has been considerably relaxed in recent years, particularly in urban areas. But consciousness of caste persist despite government interventions.

Below the four castes outlined above were the Dalits, i.e. people outside the caste system also known as outcastes or untouchables who performed work considered ‘dirty’. Historically marginalized and subjected to severe discrimination and exclusion, they have faced significant barriers to social and economic mobility. They have been relegated to the most menial and degrading jobs and denied access to resources, education, and public facilities. Despite legal protections and affirmative action policies introduced in India since its independence, such as the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, Dalits continue to struggle against entrenched social prejudices and systemic discrimination. Efforts by Dalit leaders, social reformers, and modern Hindu movements have aimed at promoting social equality and dismantling caste-based discrimination, advocating for a more inclusive interpretation of Hindu teachings that emphasize the inherent dignity and equality of all individuals.

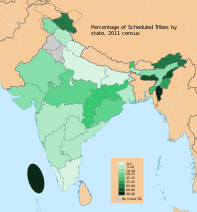

Source: “2011 Census Scheduled Caste caste distribution map India by state and union territory” by M Tracy Hunter via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Source: “2011 Census Scheduled Tribes distribution map India by state and union territory” by M Tracy Hunter via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

The Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) constitute approximately 16.6% and 8.6% of India’s population, respectively, according to the 2011 census. Since India gained independence, SCs and STs have been granted Reservation status, ensuring their political representation, preferential treatment in promotions, university quotas, free and stipended education, scholarships, access to banking services, and various government schemes. The Constitution outlines the general principles of positive discrimination to support the social and economic upliftment of these communities.

China: Buddhism and the Dalai Lama

Conflict between the doctrine of communism and the authority of Buddhist religious leaders is especially acute in Tibet, China. The conflict between the Dalai Lama and China is rooted in a complex history of political and cultural tensions. The Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, is the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism and was also the political leader of Tibet before the Chinese government took control of the region in 1951. The Chinese Communist Party, led by Mao Zedong, sent troops into Tibet in 1950, asserting that the region was historically part of China. This led to the signing of the Seventeen Point Agreement in 1951, which ostensibly guaranteed autonomy for Tibet while affirming Chinese sovereignty. However, the Chinese sought to reduce the domination of Buddhist traditions by attacking the economic and cultural pillars of daily life. Monasteries and temples were destroyed and people were required to work on agricultural communes rather than in their traditional jobs as herdsmen. This lead to increased tensions and unrest in the region.

Source: “Dalailama1 20121014 4639” by christopher via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Tibetan Buddhists believe that when the Dalai Lama dies, his spirit enter the body of a child so that the leader is reincarnated. A search committee of high lamas and monks interpret certain signs to find the reincarnation. They travel to regions indicated by the signs, conducting tests and rituals to verify candidates. A child who correctly identifies items belonging to the previous Dalai Lama is considered the true reincarnation. This child then undergoes religious training, with the recognition endorsed by the Tibetan government-in-exile and high lamas. The formal enthronement ceremony marks the child’s official recognition as the new Dalai Lama, with full duties assumed gradually. The current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, has suggested that the process might be modified due to the political situation with China, including the possibility of selecting the next Dalai Lama from outside Tibet or through alternative methods. However, the Chinese government insist on finding the next leader in China and they accuse Buddhist leaders of plotting to restore Tibet as an independent country.

In 1959, a major uprising against Chinese rule erupted in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital. The Chinese military suppressed the rebellion with significant force, leading to the deaths of thousands of Tibetans and the eventual flight of the Dalai Lama to India. The Dalai Lama established a government-in-exile in Dharamshala, India, where he continues to advocate for the rights and autonomy of the Tibetan people. The Chinese government, meanwhile, has maintained strict control over Tibet, implementing policies that many Tibetans and international observers view as repressive. These include restrictions on religious freedom, cultural practices, and movement, as well as efforts to assimilate Tibetans into the dominant Han Chinese culture.

The Dalai Lama has consistently called for greater autonomy for Tibet rather than full independence, proposing the “Middle Way” approach, which seeks genuine autonomy within the framework of the Chinese constitution. Despite these conciliatory efforts, the Chinese government has remained intransigent, viewing the Dalai Lama’s influence as a threat to its sovereignty and territorial integrity. The issue remains a significant point of contention in international relations, with various countries and human rights organizations calling on China to engage in dialogue with the Dalai Lama and to respect the cultural and religious rights of the Tibetan people. The situation in Tibet continues to be a sensitive and highly charged issue, reflecting broader concerns about human rights and self-determination in the face of state power.

Religious beliefs and histories can bitterly divide peoples who speak the same language, have the same ethnic background, and make their living in similar ways. Such divisions are not only between followers of different major religions (like Muslims and Christians in the former Yugoslavia). They sometimes emerge among believers of the same overarching religion. Indeed, some of the most destructive conflicts have pitted Christian against Christian and Muslim against Muslim.

Religious conflicts usually involve more than differences in spiritual practices and beliefs. Religion serves as a symbol of a wider set of cultural and political differences. The “religious” conflict in Northern Ireland is not just about different views of Christianity, and the conflict between Hindus and Muslims in India has a strong political dimension. Nevertheless, in these and other cases, religion serves as the principal symbol separating competing groups.

Many times conflict arises at interfaith boundaries, boundaries that divide two major world religions. Many of these countries have faced divisive cultural forces, especially when religious differences are viewed as the primary source of social identity. This situation is evident in several African countries that straddle the Christian–Muslim interfaith boundary. Check Figure 8.6.1.

Nigeria: Conflict with Boko Haram, a fundamentalist group

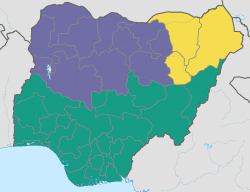

Source: “Use of Sharia in Nigeria” derivative work of Underlying lk via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Source: “Religion distribution Africa crop” derivative work of T L Miles by Moshin via Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain.

Similar to other countries in West Africa, Nigeria is predominantly Muslim in the north and Christian and animist in the south. Since 1999, when the country transitioned from years of military rule, Nigeria has experienced persistent violence along the interfaith boundary between these communities, resulting in hundreds of thousands of lives lost.

As Figure 8.6.2 clearly shows, much of the North is Islamic; approximately half of these Islamic states follow Sharia law, while the other half (the yellow portion of the map) is an area where Islamic law applies to personal status issues such as marriage only. Boko Haram rebels aim to make north- ern Nigeria an Islamic state. More than 4,700 people have died in violence that first erupted in 2009 in the northeast city of Maiduguri. Half have been killed in Boko Haram attacks on government institutions, churches, and secular schools. An equal number, many with no ties to the terrorists, have died in government counterattacks.

Source: “Nigerian-deforrestation-b” by FrankvEck via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Islamic and Christian groups converge in the middle part of the country, a region known as the Middle Belt, where Muslim, Christian, and animist communities now coexist. As with many such conflicts, the cause of north-south violence in Nigeria cannot be attributed solely to different religious beliefs. Due to climate differences, many people in northern Nigeria engage in cattle herding, whereas most rural inhabitants in the south are farmers. As land has become scarcer (see Figure 8.6.3), the fertile grasslands of central Nigeria have become coveted by both cattle herders and farmers. Land once reserved for grazing has gradually been replaced by agriculture, and violence against herders is often justified as retaliation for acts of trespassing on planted fields and crop destruction by cattle.

“Nigerian States by estimated GDP, 2021” by Karimbobboi via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The north and south of Nigeria also vary in several other aspects. The oil-rich economy and the employment opportunities it generates are predominantly found in the south. As a result, the southern region enjoys a higher per capita GDP and a greater accumulation of wealth compared to the north. Moreover, while the Hausa-Fulani ethnic group is the majority in northern Nigeria, the southern region is more ethnically diverse. Western-style education is more widely accepted in the south, leading to higher female literacy rates. Lastly, access to healthcare is better in the south.

8.6.2 Challenges for Religions in Southwest Asia

Israel: A longstanding Conflict over Land

Conflict in this portion of Southwest Asia is among the world’s longest standing and most intractable. Jews, Christians, and Muslims have fought for many centuries to control the same small strip of land.

Source: “Figure 8.24 The Western Wall in Jerusalem” in World Regional Geography by R. Berglee via University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

The control of Israel has been fiercely contested due to its significance to three major Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. This region, often referred to as the Holy Land, is believed to be the ancestral homeland promised to Abraham and his descendants in Jewish and Christian traditions. It is also revered as the site of key events in the lives of prophets and the birthplace of Jesus Christ in Christianity. For Muslims, Jerusalem is the third holiest city after Mecca and Medina, being the location of the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque, associated with the Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey. Throughout history, this shared religious importance has made the land of Israel a focal point of conflict and contention. Various empires, kingdoms, and religious factions have fought for control over Jerusalem and its surroundings, leading to numerous wars, conquests, and occupations. The Crusades, Ottoman rule, British mandate, and the Arab-Israeli conflicts are all manifestations of this enduring struggle for religious, cultural, and political dominance in a region that holds profound spiritual significance for millions worldwide.

The land of Israel holds profound significance in the development of Judaism. It served as the historical and spiritual center where key events in Jewish history, such as the lives of the patriarchs, the establishment of the First Temple in Jerusalem, and the teachings of the prophets, unfolded. This land, often referred to as the Promised Land, not only shaped Jewish identity and religious practice but also inspired the enduring connection between the Jewish people and their ancestral homeland, even during periods of exile and dispersion. This historical and spiritual bond continues to influence Jewish faith, culture, and aspirations today, including the establishment of the modern state of Israel.

Source: “Cia-is-map2” by Central Intelligence Agency is in the public domain.

The state of Israel is bordered by Lebanon to the north, Syria and Jordan to the east, and Egypt to the south. Covering an area of only 8,522 square miles, Israel is smaller than the US state of Massachusetts and only one-fifth the size of the state of Kentucky. Israel is quite an ethnically diverse state with Jewish majority. Before Israel’s establishment in 1948 the country was called Palestine, its people Palestinians who were primarily Arab Muslims, Samaritans, Bedouins, and Jews. Before 1948, most Jewish people were dispersed throughout the world, with the majority in Europe and the United States.

Historically, Palestine was a part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire before the end of World War I. Britain defeated Turkish forces in 1917 and occupied Palestine for the remainder of the war. The British government was granted control of Palestine by the mandate of the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919 at the end of World War I. Britain supported the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which favored a Jewish homeland. The British Mandate included Palestine and Transjordan, the area east of the Jordan River, which includes the current country of Jordan.

Between 1922 and 1947, under British control, Palestine was predominantly Arab and Muslim, with Jews comprising less than 20% of the population. Jewish settlements were primarily located along the west coast and in the north, with additional migration occurring, notably by Jews fleeing German oppression in the 1930s. After World War II, in 1945, Palestine was placed under the administration of the newly formed United Nations (UN).

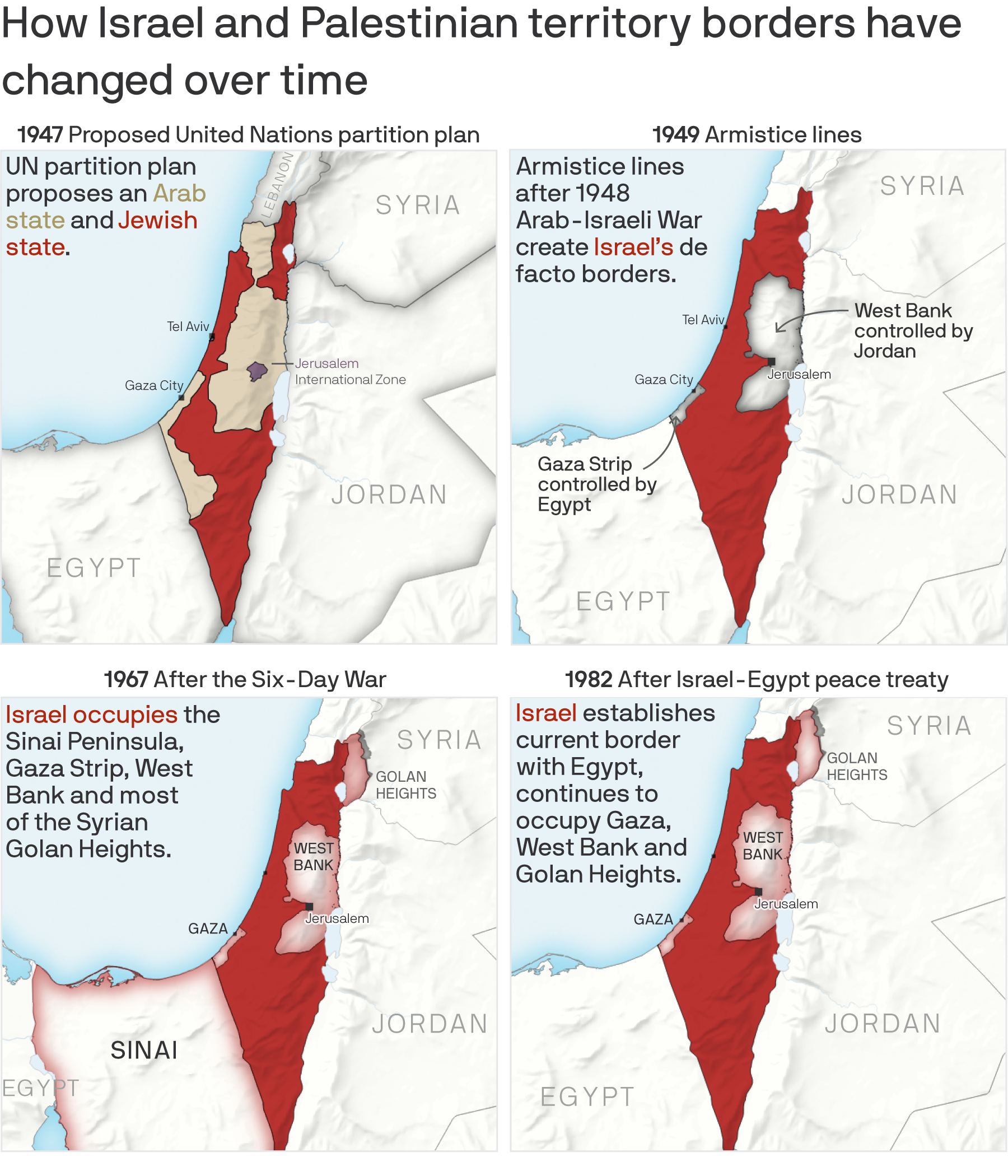

The United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) was created by the UN in 1947. To address the Palestine region, UNSCOP recommended that Palestine be divided into an Arab state, a Jewish state, and an international territory that included Jerusalem. About 44% of the territory was allocated to the Palestinians, who made up 67% of the population. Approximately 56% of the territory was allocated to the minority Jewish population which amounted to at 33%. The country of Jordan was created out of the region east of the Jordan River and the Dead Sea. The city of Jerusalem was to remain under the administrative control of the UN as an international city.

The Jewish State of Israel was officially recognized in 1948. The Palestinians, who were a majority of Israel’s total population at the time denounced the agreement as unacceptable. One of the consequences of the territorial partition was that thousands of Palestinian Arabs were forced off the land that was allocated to the Jewish state. These Palestinians became refugees in the Palestinian portion or in neighboring countries.

Arab-Israeli Wars

The conflict in the Middle East is now played out primarily among various countries and groups of people aspiring to control territory. But differences in religious traditions and their uses in nationalist ideologies underlie the origins of the conflicts and the challenges in peacefully resolving them.

Here is a listing of conflicts that helped shape the modern geopolitical landscape of the Middle East, influencing regional dynamics, peace negotiations, and international relations.

- 1948 Arab-Israeli War: Immediately following Israel’s declaration of independence, neighboring Arab states invaded, seeking to prevent the establishment of the Jewish state. Israel successfully defended itself and expanded its territory.

- Suez Crisis (1956): Not a conventional war, but a conflict involving Israel, Egypt, the UK, and France. Israel, with support from the latter two, occupied the Sinai Peninsula and sought to reopen the Suez Canal after Egypt nationalized it. Egypt sought to blockade international waterways near its shores that Israeli ships were using.

- Six-Day War (1967): Israeli neighbors blocked Israeli ships from using international waterways. Israel launched preemptive strikes against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, resulting in a swift and decisive victory. Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank, and Golan Heights.

- War of Attrition (1967-1970): A prolonged conflict primarily between Israel and Egypt, characterized by continuous border clashes and aerial battles along the Suez Canal and Sinai Peninsula.

- Yom Kippur War (1973): Egypt and Syria launched surprise attacks on Israel during the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur. Despite initial setbacks, Israel repelled the attacks and maintained control over the Sinai and Golan Heights.

- Lebanon War (1982): Israel’s military intervention in Lebanon aimed at removing the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) threat from its northern border. It led to a prolonged conflict with Lebanese and Palestinian forces.

In 1980, Israel passed the Jerusalem Law, which stated that greater Jerusalem was Israeli territory and that Jerusalem was the eternal capital of the State of Israel. The UN rejected Israel’s claim on greater Jerusalem, and few if any countries have accepted it. Israel moved its capital from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem to solidify its claim on the city even though most of the world’s embassies remained in Tel Aviv until very recently former President Trump decided to declare Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and relocated the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Palestinians were left with only the regions of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, which is controlled by the Israeli government and is subject to Israel’s national jurisdiction. Before the present conflict 2023/2024 about 2 million Palestinians lived in the Gaza Strip and about 3 to 4 million lived in the West Bank.

PLO vs. PA

The Palestinian Authority (PA) exercises municipal authority over Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT), managing local affairs. In contrast, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) makes broader decisions concerning Palestinians globally and the status of Palestine, yet lacks legal authority over internal governance. The PLO, as the signatory to the Oslo Accords, negotiated the creation of the PA, which was established to implement these agreements.

A number of cities in the West Bank and Gaza Strip have been turned over to the Palestinian Authority (PA) for self-governing. The PA was established between the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Israeli government to administer internal security and civil matters. The PLO is the internationally recognized governing body of the Palestinian people. It is legitimately recognized by the UN to represent the area known as Palestine in political matters. There are two main political parties within the PLO: Hamas, an Islamist party, and Fatah, a secular party. The Hamas party is the strongest in the region of the Gaza Strip, and the Fatah party is more prominent in the West Bank.

Source: “How Israel and Palestinian territory borders have changed over time” Data: Axios research. (Depicts region after the end of the British Palestine Mandate. Not shown are Israeli settlements in the West Bank.) Map: Will Chase and Jacque Schrag/Axios retrieved from “Maps Tell the Story of the Palestinians and the State of Israel” by Axios, Saturday Edition 10/21.

Possible Solutions for Palestinians and Israel

The future of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip has been the focus of talks and negotiation for decades. Proposals included a one-state solution and a two-state solution. The one-state solution proposes the creation of a fully democratic state of Israel and the integration of all the people within its borders into one country. Integration of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank into the Jewish State of Israel is part of this plan. Many Palestinians support the one-state solution, but most of the Jewish population does not. Since the family size is much larger on the Palestinian side, it is feared that it would be only a matter of time before the Jewish population would be a minority population and would not have full political control with a democratic government. To have the Jewish State of Israel, the Jewish population wants to keep its status as the majority.

Source: “Figure 8.26 Security Wall between Israel and the West Bank” in World Regional Geography by R. Berglee via University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

In a two-state solution, Palestinians would have their own nation-state, which would include the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. The rest of former Palestine would be included in the Jewish State of Israel. The two-nation concept (Israel and a Palestinian state) has been proposed and supported by a number of foreign governments, including the United States. Implementation of a two-state solution is, of course, not without its own inherent problems. At the present time, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip are subjects under the Jewish State of Israel without full political or economic autonomy. The two-state solution would buy more time for the Jewish population with smaller families to retain power as a majority political voting bloc.

Parties to the negotiations have acknowledged that the most likely solution is to create a Palestinian state bordering Israel. However, it is not clear how to make this happen. Palestine is now divided between the Jewish State of Israel (with 7.3 million people) on one side and the Palestinians (with 5.0 million people) in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip on the other side. About 75 percent of Israel’s population of 7.3 million people are Jewish, and about 25 percent are Arab. Travel between Israel and the Palestinian areas is heavily restricted and tightly controlled. A high concrete and barbed wire barrier separates the two sides for much of the border. The West Bank provides fresh water used on the Israeli side for agriculture and industrial processes. The industries also employ Palestinians and support them economically.

Jewish people from various parts of the world continue to migrate to Israel, and the Israeli government continues to build housing settlements to accommodate them. Since the West Bank region is under the Israeli national jurisdiction, many of the new housing settlements have been built in the West Bank. The Palestinians who live there strongly oppose these settlements. In 1977, only about five thousand Jews lived in the West Bank settlements; in 2022 Jewish settlements passed the half million mark. The Palestinians argue that if they were to have their own nation-state, then the Jewish settlements would be in their country and would have to be either resettled or absorbed. Israel responds by indicating that the two-state solution is indefensible because the Jewish settlements in the West Bank cannot be protected if the West Bank is separated from Israel.

The central problems remain: Jews and Palestinians both want the same land, both groups want Jerusalem to be their capital city, and neither group can find a compromise. Support for the Jewish State of Israel has primarily come from the United States and from Jewish groups external to Israel. There are more Jews in the United States than there are in Israel, and the US Jewish lobby is powerful. Israel has been the top recipient of US foreign aid for most of the years since 1948. Through charitable donations, US groups provide Israel additional billions of dollars annually. Foreign aid has given the Jewish population in Israel a standard of living that is higher than the standard of living of many European countries.

In the past decade, most of the PLO’s operating budget has come from external sources as well as Arab neighbors provide millions of dollars annually. Though Iran is not Arab, they have provided aid to the Palestinian cause in support of fellow Muslims against the Jewish State of Israel. The PLO has received the bulk of its funding from the European Union. Russia has also provided millions of dollars in aid. The United States provides millions in direct or indirect aid to the Palestinians annually.

In 2006, both Israel and the PLO held democratic elections for their leaders. In 2006, a candidate from the Hamas party won the election for the leadership of the PLO, which concerned many of the PLO’s external financial supporters. The Israeli government characterizes Hamas as a terrorist organization that supports the destruction of the State of Israel. Hamas has advocated for suicide bombers to blow themselves up on populated Jewish streets. The conflict between Hamas and Israel intensified in recent years due to a variety of factors, including political tensions, territorial disputes, and retaliatory acts of violence. Hamas, controlling the Gaza Strip, has launched numerous rocket attacks into Israeli territory, leading to military responses from Israel. This cycle of violence has resulted in significant casualties and destruction, culminating in the October 7, 2023 attacks on Israel where 1,200 people were brutally killed further complicating efforts toward a peaceful resolution.

In 2008 Mahmoud Abbas from the Fatah party as president of the State of Palestine. In 2024, Abbas appointed his longtime economic adviser Mohammed Mustafa to be the next prime minister in the face of US pressure to reform the Palestinian Authority (PA) as part of Washington’s post-war vision for Gaza. He is supposed to re-unify administration in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, lead reforms in the government, security services and economy and fight corruption. Israel, meanwhile, said it will never cooperate with any Palestinian government that refuses to reject Hamas and its October 7 attack on southern Israel.

Even if the present mission to eliminate the Hamas threat is successful, the problems between Israel and Palestinians are far from settled. The region has plenty of interconnected concerns. Israel has nuclear weapons, and Iran has worked at developing nuclear weapons. US involvement in the region has heightened tensions between Iran and Israel. Oil revenues are driving the economies of most of the Arab countries that support the Palestinians. Oil is an important export of the region, with the United States as a major market. The difficulties between Israel and the Palestinians continue to fuel the conflict between Islamic fundamentalists and Islamic reformers. Some Islamic groups have accepted Israel’s status as a country and others have not. The Israel-Palestinian problem drives the geopolitics of the Middle East.