Chapter 7: Race and Ethnicity

7.2 Race

7.2.1 Race and Human Biology

Physical anthropologists have identified several important concepts regarding the true nature of humans’ physical, genetic, and biological variation that have discredited race as a biological concept. Many of the issues pertaining to this topic are discussed in further detail in Race: Are We So Different, a website created by the American Anthropological Association.

Since World War II, research has demonstrated that racial categories are socially and culturally constructed concepts. The definitions and labels attributed to races vary significantly across different countries. Concurrently, extensive genetic studies conducted by physical anthropologists since the 1970s have established that distinct biological human races do not exist. Molecular anthropology, or anthropological genetics, revolutionized and continues to add new layers to our understanding of human biological diversity and the evolutionary processes that gave rise to the patterns of variation we observe in contemporary populations. While humans exhibit variations in physical and genetic traits like skin color, hair texture, and eye shape, these differences do not provide scientifically accurate criteria for classifying racial groups biologically.

Anthropologists use the term “cline” to describe variations in traits across human populations in different geographical regions. For instance, a trait may be more prevalent south of the Sahara Desert than north of it, but these differences are gradual and continuous without distinct boundaries.

Consider skin color as an example. Do all white individuals you know share the same skin tone? Similarly, do all Black individuals share identical skin tones? Clearly not, as human skin color spans a spectrum from very light to very dark, encompassing countless hues, shades, and tones.

Imagine two people standing together—one from Norway and one from Nigeria. If we only focus on these two individuals without considering the populations between Norway and Nigeria, it might appear that they represent two distinct racial groups: one light (“white”) and one dark (“black”). However, traveling from Nigeria to Norway reveals a broader perspective on human skin color, showing that it generally becomes lighter as we move north from the equator. North Africans tend to have lighter skin than Central Africans, and southern Europeans typically have lighter skin than North Africans. Northern Italians have lighter skin than Sicilians, and populations in Ireland, Denmark, and Sweden tend to be lighter-skinned than those in northern Italy and Hungary. This gradual change in skin color illustrates that it cannot serve as a definitive marker for racial distinctions.

There are exceptions to these observations: Certain northern regions, such as Eastern Siberia and the Arctic, are inhabited by Inuits who are darker-skinned populations despite their high geographic latitudes. This contrasts with lighter-skinned Eurasian groups like Scandinavians at similar latitudes. Physical anthropologists attribute this to the unique dietary practices of Arctic indigenous peoples, who traditionally consume Vitamin D-rich foods such as polar bears, whales, seals, and trout.

The relationship between skin color and Vitamin D is intriguing. Dark skin provides protection against intense sunlight in tropical areas by blocking harmful ultraviolet rays, which can cause skin cancer and deplete folate levels crucial for reproduction. Melanin, the skin pigment, acts as a natural sunscreen, preserving skin cells and folate. However, sunlight exposure also stimulates Vitamin D production, essential for bone health and immune function. In regions with weaker sunlight, like higher latitudes, lighter skin appear to have evolved to ensure adequate Vitamin D synthesis. Yet, Arctic populations’ diet rich in Vitamin D sources mitigated this selective pressure, maintaining darker skin tones among the Inuit and Chukchi.

Anthropologist Nina Jablonski (2012) suggests another factor: in Arctic regions, where sunlight reflects intensely off snow and ice, darker skin may have been advantageous in protecting against high ultraviolet radiation during summer months.

There are no specific genetic traits exclusive to any racial group. For human races to have biological significance, multiple genetic traits would need to consistently classify individuals into the same racial categories. For instance, a racial classification based on skin color should align with classifications based on blood type, hair texture, eye shape, lactose intolerance, and other traits often incorrectly presumed to be racial markers.

Consider sickle-cell anemia, often mistakenly associated solely with Africans and African Americans. The sickle-cell allele, causing the disease, is prevalent among populations from regions where malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum is endemic, including Central and Western Africa, parts of Mediterranean Europe, the Arabian Peninsula, and India. Thus, the sickle-cell trait is not exclusive to African or Black populations, despite misconceptions.

Similarly, the epicanthic eye fold, often linked with East Asian ancestry, is also found in Central Asians, parts of Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, some American Indian groups, and the Khoi San of southern Africa. This demonstrates that traits commonly used to define race do not strictly adhere to racial boundaries as conventionally understood.

The concept of biological human races tends to highlight perceived differences between groups while overlooking diversity within groups. In reality, the vast majority of genetic diversity in humans (88–92 percent) exists within populations on the same continent, emphasizing the complexity and fluidity of genetic traits across human populations.

PBS Website RACE – The Power of an Illusion

PBS has created an exciting website called RACE – The Power of an Illusion that looks at whether race indeed is a biological characteristic of humans or a social construct. Take the Sorting People quiz and watch The Human Family Tree and Black in Latin America: An Island Divided to “witness” how migration and geography play a role in the complex issues surrounding race and ethnicity. Pay attention to how the racial and ethnic landscape of the island of Hispaniola impacts cultural identity and the geopolitics both within Hispaniola and beyond its shores.

7.2.2 Race as a Social Construct

So, race does not exist, then? Yes, race does exist, but it is a construct shaped by arbitrary social and cultural definitions rather than biological or scientific principles. Therefore, racial categories like White and Black hold a reality akin to categories such as “American” and “African.” Many aspects of the world are real yet lack biological basis. Hence, while race lacks biological underpinnings, it represents socially constructed ideas that societies subjectively define to signify perceived divisions deemed significant. Consider, for example, the Irish Catholics, who were seen as racially different and inferior in the mid-1800s, or the Italians and the Jews in the early 20th century, who were seen as ‘Mediterranean’ and ‘Jewish’ races, respectively. However nowadays the aforementioned ethnic groups are seen as ‘white’; a development over time that may have been hastened by their acquisition of wealth. Some sociologists and anthropologists now prefer the term “social races” to underscore their cultural and arbitrary origins.

7.2.3 Different Countries, Different Social Constructs of Race – United States, Brazil, Japan

United States: Race has historically been portrayed as rigid and strictly delineated. Americans have traditionally viewed racial categories as distinct and mutually exclusive; for instance, individuals with one Black parent and one white parent were typically categorized solely as Black. The institution of slavery profoundly influenced how racial classification evolved in the United States, notably through the implementation of the one-drop rule. This rule mandated that any traceable non-European ancestry automatically precluded an individual from being classified as white. The one-drop rule was initially designed to ensure that children resulting from sexual relationships—often but not always coerced—between slave-owning men and enslaved women would inherit the status of slavery.

Only recently did the United States government, the media, and pop culture officially acknowledge and embrace biracial and multiracial individuals. The 2000 census was the first to allow respondents to identify as more than one race.

Brazil: Both countries came into existence as they are today due to European colonialism in the New World. They established major plantation economies that relied on large numbers of African slaves, and post abolition of slavery, experienced large waves of immigration from around the world, particularly Europe.

In Brazil, races are commonly seen as points along a continuum where one gradually transitions into another. White and Black represent opposite ends of this continuum, which includes numerous intermediate racial labels based on color that lack equivalents in the United States. The Brazilian term for these categories, which correspond to the concept of race in the United States, is tipos meaning types’.Tipos describe slight but noticeable differences in physical appearance, looking at complexion, hair texture and color, eye color, lips and nose.

Sociologists and anthropologists have identified over one hundred twenty-five tips in Brazil, with small villages of just five hundred people, sometimes having forty or more, depending on how residents describe each other. These labels can vary from one region to another, reflecting local cultural distinctions.

Another significant contrast in how race is perceived between the United States and Brazil lies in the more flexible and adaptable nature of racial identity in Brazil. This is encapsulated in a popular Brazilian saying: “Money whitens.” In Brazil, as individuals with darker complexions rise in social status—such as through obtaining higher education and securing well-paid professional roles—they often come to be seen as belonging to a somewhat lighter tipo. Conversely, light-complexioned individuals who experience economic decline may be perceived as belonging to a slightly darker tipo.

In the United States, however, social class does not influence one’s racial categorization. A non-white person who achieves upward social mobility through education and wealth accumulation may be viewed as more socially esteemed due to their class status, but their racial classification remains unchanged.

Brazil’s fluid approach to race is, for all intents and purposes, accompanied by generally more harmonious and benign social interactions among individuals of varying colors and complexions. This perception has led to Brazil being labeled as a “racial paradise” and a “racial democracy,” distinct from other multiracial nations like the United States and South Africa, which have historically been marked by harsh prejudices and societal discrimination. However, this is not so.

Source: “Map – Human Development Index of Brazilian municipalities in 1991, 2000, and 2010” retrieved from Silva, S. A. da. (2019). Regional inequalities in Brazil: Divergent readings on their origin and public policy design. EchoGéo (48). https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.15060

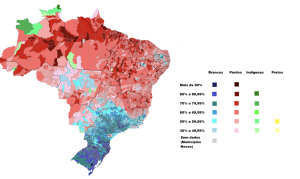

Source: “A map of predominant racial groups by municipality” by Magno Brasil via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

When comparing the status of human development with the inhabitants of the areas in Brazil (see the maps on Figure 7.2.2 and 7.2.3 above) it becomes evident that high or very high human development corresponds with the populations being mostly light-skinned. The majority of the country’s Afro-Brazilians live in the less-affluent northern region, the site of the original sugar cane plantations, while the majority of Brazilians of European descent live in the industrial and considerably wealthier southern region.

Japan: Japan represents an example of a third way of constructing race that is neither influenced by Western societies nor African slavery.

Japan’s population, known as the Burakumin, has historically faced discrimination. The Burakumin are a social minority group that has been subjected to prejudice and social exclusion due to their ancestral association with occupations considered impure or tainted, such as butchery, leatherwork, and undertaking. These occupations were deemed impure under Buddhist and Shinto beliefs, leading to the Burakumin being socially marginalized. Up to the mid-19th century, the Burakumin were officially segregated and forced to live in separate communities. While this caste system was abolished in 1871, the stigma lived on. Despite legal equality, Burakumin often faces social discrimination in various aspects of life, including marriage, employment, and education. Some employers and families still avoid Burakumin based on hidden registries and ancestral records.

Source: “Foreign residents in Japan” by Yuasan via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC0.

The Japanese government has implemented laws and policies aimed at reducing discrimination against the Burakumin. For example, the “Law on Special Measures for Dowa Projects” was enacted to improve living conditions in Burakumin communities. While significant progress has been made in addressing formal discrimination, more needs to be done.

In addition, there is the problem of xenophobia. Figure 7.3.4 demonstrates that Japanese society is diverse; the number of Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Brazilian immigrants began to increase in the 1980s and has been doing so ever since. According to CNN January 29, 2024, three such ‘foreigners’, one with Japanese citizenship, sued the government for racial discrimination as they felt repeatedly profiled and stopped by police. This is just one of the instances that have come to international attention. In the article Why does Japanese society overlook racism? the author Yoshitaka cites three significant cites three reasons that hinder the Japanese public from acknowledging the problem: 1. the Japanese government claims there is no racism in the country; 2. the Japanese census does not collect data on ethnicity or race, giving the impression that all Japanese are one single ethnic group and 3. Japanese politicians tout the existence of a monoethnic group even though Japan has always been characterized by diverse cultures and customs that vary across regions, alongside a rich linguistic diversity including Ainu, Uchinaguchi (Okinawan), and Japanese Sign Language. The country also has a history marked by migratory movements and nomadism.