Chapter 7: Race and Ethnicity

7.7 Ethnic Landscapes – Large-Scale

7.7.1 Forced Migration of Slaves from Africa

Most African Americans are descended from Africans forced to migrate to the Western Hemisphere as slaves during the 18th century, Most but not all Asian and Hispanic Americans are descended from voluntary immigrants to the United States during the late 20th and early 21st century.

Slavery and the Triangular Slave Trade

The Atlantic slave trade began shortly after the arrival of the Spanish and Portuguese in the Americas. The transatlantic leg of the African slave trade most likely began with a Portuguese slaving voyage from Africa to the Americas in 1526. The earliest efforts were copied and accelerated by later Portuguese, British, French, and Dutch voyages. Overall, between the 16th and 19th centuries, approximately 12.5 million Africans were taken from the coast of Africa to the Americas, though about 2.5 million of those died during the voyage.

Source: “Map of both intercontinental and transatlantic slave trade in Africa” by KuroNekoNiyah via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade to the New World was part of a broad exchange of trade goods between England, West Africa, South America, the West Indies, and the United States. While the largest numbers of slaves were sent to South America, particularly Brazil, and the West Indies, smaller numbers arrived in the United States where Americans purchased them for labor. Most often from the west and central portions of the African continent, these enslaved people were kidnapped, forced to endure extreme violence, ripped from family and familiar language and culture, and treated as property. They endured the Middle Passage, the journey by ship from West African slave trading ports to the New World.

Source: Photo by Barbara Crain, CC BY 4.0.

While many of the slavers were Africans, it was European demand and economic power that drove and amplified the trade. Europe needed the labor, and African traders supplied it, turning slavery into a major business. As more enslaved people were sent to European colonies in the Americas, numerous African communities collapsed.

Source: Photo by Barbara Crain, CC BY 4.0.

Source: Photo by Barbara Crain, CC BY 4.0.

Source: Photo by Barbara Crain, CC BY 4.0.

From the European point of view, slave labor was crucial for economic production and increasing wealth. The expansion of plantation agriculture from Brazil into the Caribbean drove the expansion of the slave trade. By the end of the trade in the 19th century, more than eight out of every ten Africans taken in bondage to the Americas had disembarked in either Brazil or the islands of the Caribbean. Sugar—so labor intensive and difficult to produce—ruled these regions and thus promoted slave trade. In Brazil, the labor conditions were so harsh that the average life expectancy for a slave was only twenty-three years. This high mortality rate, in turn, created more of a slave demand.

Once in the United States, enslaved Africans were sold at auctions across the country, from the rice plantations of the South Carolina coast to the small businesses and farms of the rural Northeast. Both England and the United States outlawed the importation of slaves through slave trading in 1807. This did not fully prevent illegal slave trading to the United States, which persisted until the American Civil War.

7.7.2 Internal Migration of African Americans in the United States

Interregional Migration

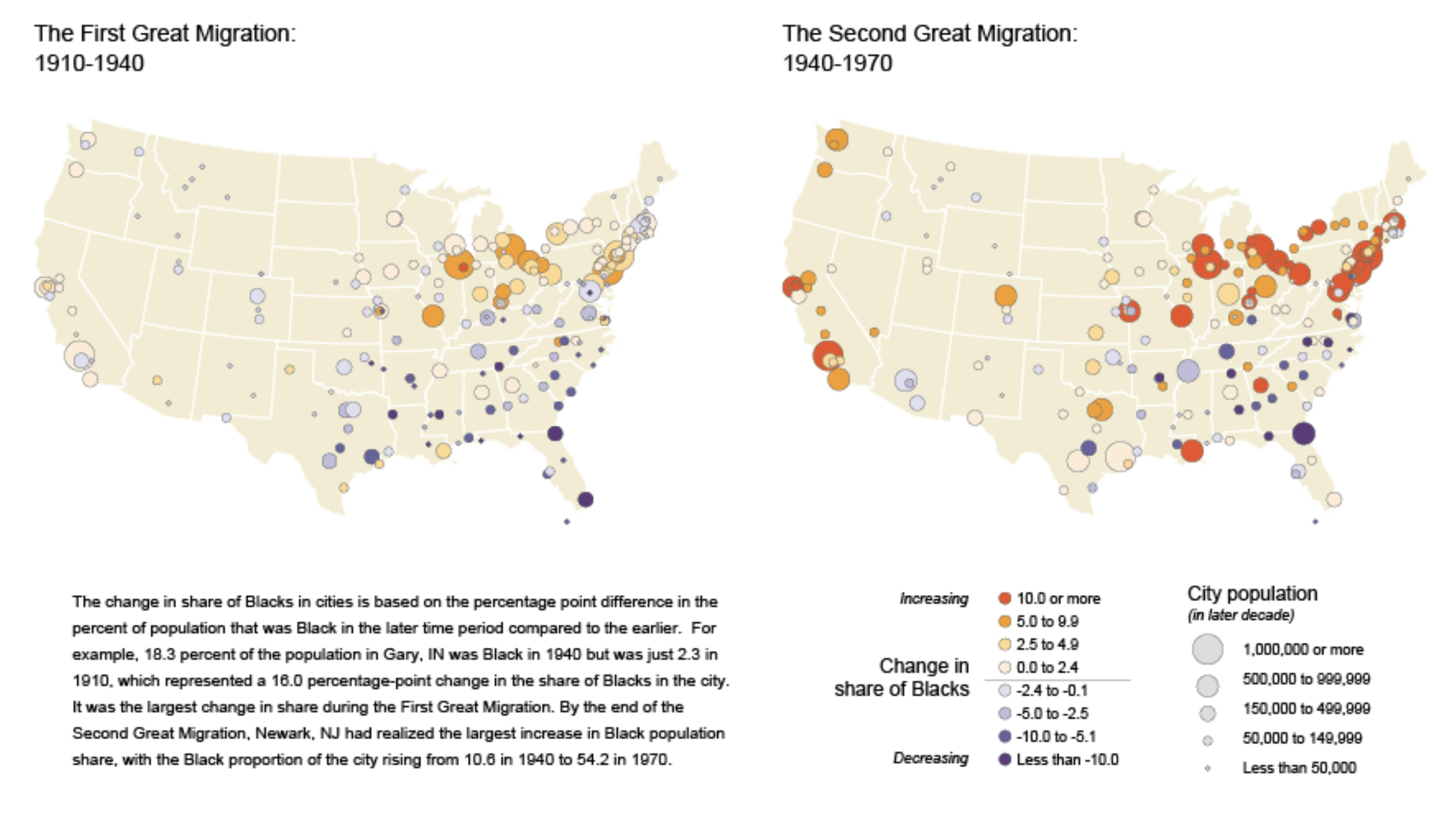

The Great Migration was one of the largest movements in U.S. history, with about six million African Americans relocating from the South to Northern, Midwestern, and Western states from the 1910s to the 1970s. They sought to escape racial violence, and oppression, and to pursue better economic and educational opportunities.

This migration occurred in two phases, linked to the U.S. involvement in both World Wars. The First Great Migration occurred from 1910-1940; the second Great Migration occurred between 1945 to 1970.

Source: “Great Migration 1910 to 1970 – Urban Population” by US Census Bureau is in the public domain.

The First Great Migration saw Black southerners move to northern and midwestern cities like New York, Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh, filling industrial jobs left vacant by men sent to fight in World War I. Despite better job opportunities, migrants faced significant challenges, including the racial violence of the Red Summer of 1919.

The Second Great Migration, from World War II to the 1970s, saw even more Black people move North and West, particularly to California cities like Oakland, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, as well as Portland and Seattle. By the end of this period, an additional three million Black individuals had relocated across the United States.

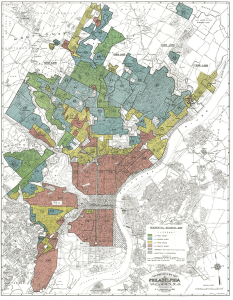

Source: “Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Philadelphia redlining map” is in the public domain.

Intraregional Migration

Those who migrated during the second phase of the Great Migration were met with housing discrimination, as localities had started to implement restrictive covenants and redlining, which created segregated neighborhoods, but also served as a foundation for the existing racial disparities in wealth in the United States. Newcomers were forced to settle where African Americans who arrived in the 19th century or a bit later already lived. Redlining systematically denied minority communities access to mortgages and other financial services. The impact of Redlining can be summed up as follows:

- Economic Disparities: Redlining led to significant economic disparities between white and minority communities. By denying loans and investment, minority neighborhoods were deprived of opportunities for homeownership, which is a major avenue for building wealth in the United States. This contributed to a persistent wealth gap between white and minority households.

- Urban Decay: Lack of investment in redlined areas resulted in deteriorating housing conditions, as property owners could not obtain the financing needed for maintenance or improvements. This often led to a cycle of decline, where disinvestment caused further decay and reduced property values.

- Segregation: Redlining reinforced racial segregation, as minority families were confined to specific neighborhoods. This segregation extended beyond housing to schools, public services, and other aspects of life, creating isolated pockets of poverty and limiting upward mobility (see White Flight below).

While overt redlining practices have been outlawed, subtle forms of discrimination and bias in lending and real estate still exist. Modern technology and data analysis have been employed to identify and combat these practices.

Suburbanization of White Residents

Starting in the 1950s through the 1980s the cities experienced the phenomenon of White Flight, i.e. the emigration of whites from an area in anticipation of African Americans moving into the area . This migration of white people to the suburbs was in part driven by factors such as increased suburban housing construction, improved accessibility via new highways, and higher incomes historically enjoyed by whites compared to African Americans. However, this explanation is incomplete because many affluent African Americans, who could also afford suburban living, did not relocate alongside their white counterparts. The disparity is widely acknowledged to be due to systemic barriers that prevented people of color from accessing homeownership opportunities in suburban areas, perpetuated by discriminatory practices by banks and real estate agents. White Flight was helped along by a process called blockbusting where real estate agents convinced white homeowners that were located in or near black areas to sell their house at low prices preying on their fears that black families would move into the neighborhood and cause the property values to decline. These processes gave rise to the inner cities as we know them today.

Suburbanization of African Americans

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s led to significant legislative and social changes. Laws like the Fair Housing Act of 1968 helped to dismantle some of the barriers that had prevented African Americans from moving to the suburbs. As African Americans began to achieve greater economic success, the desire to move to the suburbs for better housing, schools, and overall quality of life increased. The rise of the black middle class – greater attainment of college degrees led to people finding and securing better-paying jobs – facilitated their move to the suburbs. In addition, many inner-city areas faced economic decline, crime, and deteriorating schools from the 1970s onwards, prompting residents, including African Americans, to seek better living conditions in the suburbs.

Suburbs themselves became more diverse over time and also became locations for employers. The perception of the suburbs as predominantly white began to change, making them more attractive to African American families. By the 2000s, a significant portion of African Americans lived in suburban areas rather than central cities.

In addition to moving to the suburbs, African Americans have been returning to the South in a New Great Migration since 1965, significantly increasing since 1990, particularly to states like Georgia, Texas, and Maryland, which have seen economic growth particularly in knowledge industries, services, and technology..

7.7.3 Segregation

Segregation in the United States

A distinctive feature of ethnic relations in the US and South Africa has been the strong discouragement of spatial interaction among some groups in the past through legal means: segregation laws. Although these laws are no longer in effect, their legacy remains fundamental to understanding the geography in both countries.

Segregation in the United States refers to the enforced separation of different racial groups in everyday life, a practice prevalent from the late 19th century until the mid-20th century It particularly affected African Americans, although other minority groups, predominantly Asians, were also impacted.

Louisiana had enacted a law that required black and white passengers to use different train cars. This concept of ‘separate but equal’ was upheld by the Supreme Court 1896 because it provided separate but equal treatment of blacks and whites. This caused Southern states to enact Jim Crow laws to enforce racial segregation. These laws mandated the separation of races in public places and services, such as schools, transportation, restrooms, and restaurants. Segregated facilities, however, were rarely, if ever, equal in quality.

Key court cases like Brown v. Board of Education helped to overturn segregation laws because the Supreme Court found that having separate schools for blacks and hites unconstitutional because no matter how equivalent the facilities, racial separation branded minority children as inferior and thus was unequal. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. advocated for nonviolent resistance. Protests, boycotts, and marches, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956) and the March on Washington (1963), drew national attention to the injustices of segregation. Finally, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were landmark laws that prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin and protected voting rights for minorities.

Source: The image is from This GIF Shows How The D.C. Area’s Demographics Have Changed Since 1970 by Rachel Kurzius, dcist.

While legal segregation was dismantled, its legacy persists as economic disparities persist due to the significant wealth gap, higher poverty rates and employment discrimination. Schools in predominantly African American neighborhoods often remain underfunded and resource-poor, perpetuating educational disparities. Many urban areas remain segregated due to historical practices and ongoing economic inequalities, affecting access to quality housing, healthcare, and services. African Americans are disproportionately affected by systemic issues in the criminal justice system, including higher rates of incarceration and police violence.

Segregation in South Africa

Apartheid was a system of institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination in South Africa that was implemented by the National Party government from 1948 until the early 1990s. The term “apartheid” is Afrikaans for “separateness,” and the policy was designed to maintain white supremacy and control over the country’s economic, political, and social systems by segregating the population based on race.

Apartheid was characterized by:

- Racial Classification: The Population Registration Act of 1950 classified South Africans into racial groups: White, Black, Coloured (mixed race), and Indian. These classifications determined every aspect of a person’s life, including where they could live, work, go to school, and whom they could marry.

- Pass Laws: At the height of Apartheid, black South Africans were required to carry passbooks that contained their personal information and details of their employment. These passes restricted their movement and employment opportunities, effectively controlling their mobility and confining them to designated areas.

-

Figure 7.7.9 Racial-demographic map of South Africa published by the CIA in 1979 with data from the 1970 South African census (Click the image to see it on Wikimedia.)

Source: “South Africa racial map, 1979” is in the public domain.Residential Segregation: The Group Areas Act of 1950 designated specific areas where different racial groups could live. Whites were allocated the best urban and rural areas, while non-whites were forced into overcrowded and underdeveloped regions known as “townships” or “Bantustans” , the homelands. The creation of the homelands was a central element of the strategy to make whites a demographic majority. The long-term goal was to make the homelands independent so that blacks would lose their South African citizenship and voting rights, allowing whites to remain in control of South Africa.

- Education: The Bantu Education Act of 1953 established separate and unequal education systems for different races. Schools for Black South Africans were severely underfunded and provided an inferior education designed to prepare them for menial labor.

- Employment: Job opportunities and wages were heavily skewed in favor of whites. Black South Africans were largely restricted to low-paying, unskilled jobs and were often barred from joining labor unions or striking.

- Political Exclusion: The apartheid regime systematically disenfranchised non-white populations. Black South Africans had no political representation and were excluded from participating in the national government. Instead, they were assigned citizenship in the Bantustans, which were nominally independent but effectively controlled by the South African government.

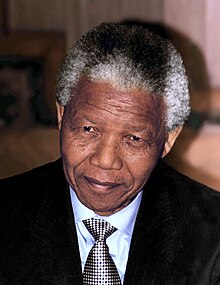

Source: “Nelson Mandela 1994” by John Mathew Smith 2001 via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Resistance to apartheid came from various quarters, including internal movements and international pressure. Internal resistance grew stronger thanks to organizations such as the African National Congress (ANC)- now the leading party in the country- and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) led campaigns of protest, civil disobedience, and armed struggle. Notable leaders like Nelson Mandela (who was imprisoned for over 27 years), Oliver Tambo, and Steve Biko became symbols of the anti-apartheid movement. Moreover, the global community condemned apartheid, leading to economic sanctions, cultural boycotts, and political isolation of the South African government. The United Nations and numerous countries imposed embargoes and trade restrictions to pressure the regime to dismantle apartheid.

The apartheid system began to unravel in the late 1980s due to the combination of above said reasons and economic pressures. Under President F.W. de Klerk, the South African government initiated reforms, including the release of Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990 and the unbanning of anti-apartheid organizations. In addition, negotiations between the government and anti-apartheid leaders led to the dismantling of apartheid laws. In 1994, South Africa held its first multiracial democratic elections, resulting in Nelson Mandela becoming the country’s first black president.

The legacy of apartheid remains evident in South Africa through ongoing economic and social disparities. The post-apartheid government has faced significant challenges in addressing the inequalities and injustices created by decades of systemic discrimination. Efforts to promote reconciliation, such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and policies aimed at redressing economic imbalances, like Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), have been central to the country’s efforts to heal and rebuild.