Chapter 7: Race and Ethnicity

7.4 Gender

7.4.1 Patriarchy

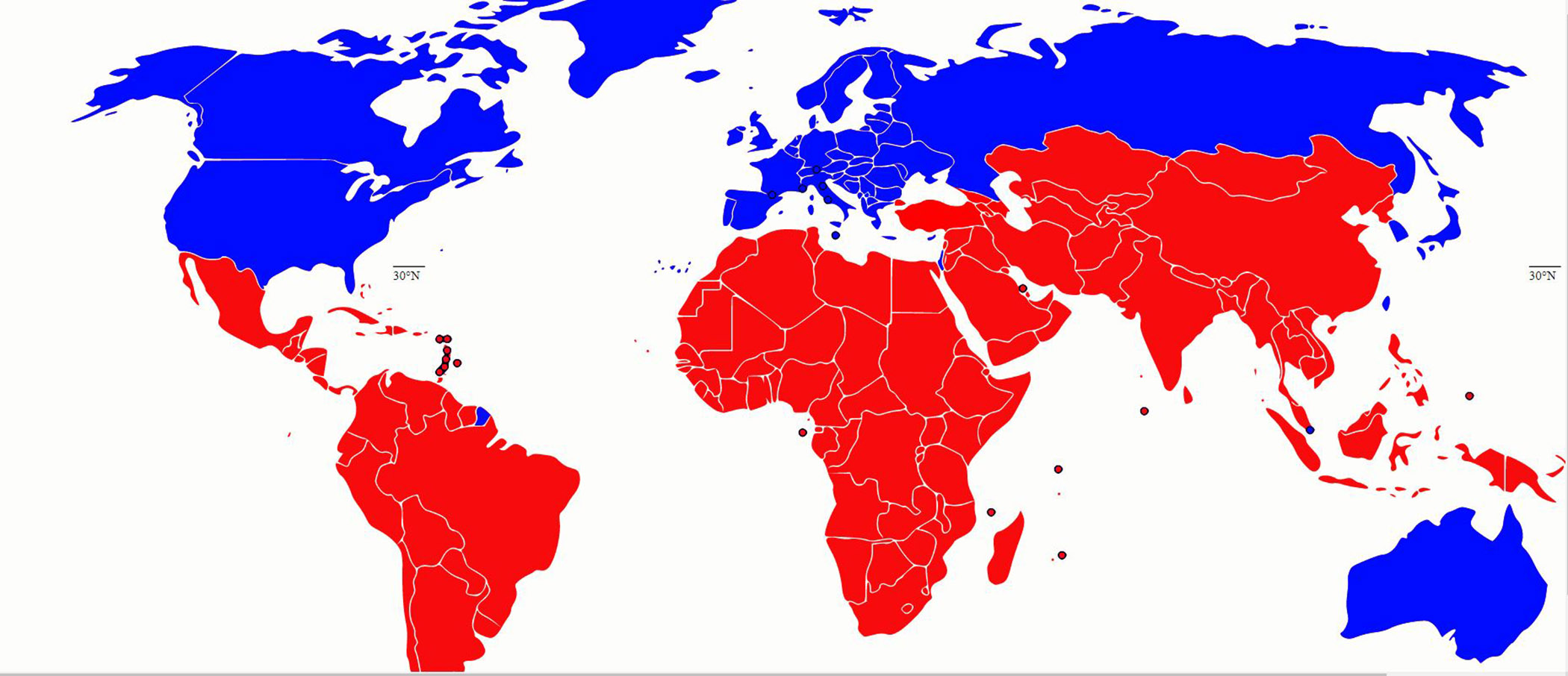

Source: “Map of Global North and Global South countries” from Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain.

In the societies of the Global North (high and higher income countries) societies, patriarchy has long been a central structural element, characterized by culturally specific symbols, behaviors, and ideas that are male-dominated, male-identified, and male-centric. This structure normalizes a binary view of gender, reinforces gender stereotypes, and limits gender roles. Patriarchy is deeply embedded in the fabric of these societies, making it difficult to see but highly influential. For example, in the Global North, patriarchy shapes rigid notions of “feminine” and “masculine” roles. This influence is evident in the expectation for cisgender men to serve in the military and for women to take on more domestic responsibilities. It is also reflected in the low number of men employed in care services like nursing and childcare, and the scarcity of women in manual labor-intensive jobs such as construction or in political leadership positions.

For example, sayings such as “boys will be boys” are often used to justify aggressive behaviors among young boys, implying such behavior is inherent and unchangeable, aligning with the cultural script for masculinity perpetuated by society. Through socialization, children learn to conform to these gender expectations from an early age, with boys allowed to exhibit aggression fitting the masculine script, while deviations can lead to social sanctions. By age two or three, children recognize gender roles and adhere to them by age four or five, reinforcing stereotypes and contributing to sexism, which manifests in access to resources like nutrition, healthcare, and education.

Consider another example. You may have heard a popular riddle that goes like this: “A father and son are in a car accident and are both badly injured. They are taken to separate hospitals. When the boy is brought in for surgery, the surgeon says, ‘I cannot operate on this boy because he is my son.’ How is this possible?” The trick (spoiler alert!) is that the surgeon is the boy’s mother. This riddle confounds many people who have been conditioned to associate being a surgeon with being a man. The idea that a woman (or mother) could be the surgeon seems so improbable that we unconsciously dismiss it. These types of ingrained associations are part of a patriarchal system that shapes how people in the Global North perceive the world and their roles within it.

Socialization continues through family, education, peer groups, and mass media, with each agent reinforcing gender-specific behaviors. Families often grant more independence to sons while expecting daughters to be passive and nurturing, and schools historically segregate boys and girls into different educational tracks. Mass media and advertisements perpetuates gender stereotypes by portraying women in less significant or stereotypically feminine roles, emphasizing beauty and domesticity while men dominate leadership and action-oriented roles. This portrayal shapes societal perceptions and contributes to ongoing gender stratification, where men hold more authoritative and higher-paying jobs. Despite advancements toward gender equality, the persistence of these stereotypes and social structures highlights the deep-rooted nature of gender stratification and the challenge of achieving true equality.

Despite the influence of patriarchy, in the Global North many of these gendered characteristics have been changing in recent years. More men and women are entering into nontraditional gender employment, and more women are taking on leadership roles. Men are increasingly active in childrearing, and some are even opting to stay home and raise children while their spouse works outside the home. Gender, and the influence of patriarchy, is in flux in the Global North.

In the Global South we also have societies with very strong preference for males as is evident when looking at the sex ratio in China or India leading to practices like female undernourishment, infanticide or abandonment. Even in countries with balanced sex ratios, gender preferences manifest in other ways, such as girls leaving school early to support their families financially. Divisions of labor and expectations around unpaid domestic work further illustrate how cultures are inherently gendered. For instance, in lower-income countries, factory jobs often favor women due to perceived advantages like being an expendable labor pool. In Southeast Asia, young women migrate for domestic work – often in the Middle East – sending remittances home to support their families. Check out this Ted Talk by Lilly Singh who is clearly a strong and amazing woman!

7.4.2 Gender in the Global North[1]

In general, by the year 2000, women in the United States on average earned seventy-one cents per every dollar that a man earned (Graf et al. 2019[2]). By 2020, that rate rose to eighty-five cents, although, paradoxically, women for the first time also made up more than half the workforce (Omeokwe 2020[3]). Transgendered people in many parts of the Global North face discrimination, violence, anemic legal protections and obstacles accessing health care, among other concerns. While we explore some of these contemporary gender-related issues in the Global North, we also recognize that gender is dynamic and responsive to larger social, cultural, and political forces.

The Global North in the twentieth century is marked by a gradual arc of increasing gender equity; however, some countries, and particular groups within these countries, continue to experience high rates of gender-based violence. In the United States, Canada, and Australia, for example, ethnic minorities and Indigenous women tend to experience the highest rates of such violence. The concept of intersectionality[4] allows us to understand the compounding factors of oppression (such as poverty, racism, sexism, social neglect, among others) that contribute to gender violence within some communities in the Global North. For instance, in the United States, murder is the third top cause of death for American Indian women, which is more than twice the rate than for white women (Heron 2018)[5]. In Canada, Indigenous women are sixteen times more likely than white women to be murdered or go missing (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019)[6]. And in Australia, aboriginal women are thirty-two times more likely to be hospitalized as a result of domestic violence and ten times more likely to die from a violent assault than non-Indigenous women (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018)[7].

Similar to the increasing awareness and sensitivity to sexual assault, societal awareness of the lived experiences of transgender and gender-diverse people has improved in recent years in the Global North. Transgendered people are those whose biological sex at birth is inconsistent with their gender identity. In addition, some Northern societies are increasingly recognizing people who do not identify as male or female, or whose gender identity is fluid. Languages are adapting to these changes by including new pronouns, verbs, and nouns. For instance, some English-speaking populations are using “they/them” or “xe/xem” instead of “he/she.” In Spanish, words ending with “a” are usually considered feminine, and those ending with “o” are usually considered masculine. However, some Spanish-speaking populations are now using the gender-neutral “x” in place of “a” or “o” at the end of words, as in “Latinx.”

7.4.3 Societies with a Third Gender

n several countries, the concept of a third gender is recognized, reflecting identities that go beyond the traditional male and female categories. This recognition is deeply rooted in cultural traditions and historical contexts, although contemporary legal and social acceptance varies significantly.

In India, hijras have been recognized as a third gender since ancient times and were granted legal recognition by the Supreme Court in 2014. Hijras often live in tightly-knit communities with their own social structures and rituals. They play significant roles in religious ceremonies and blessings, especially during childbirth and weddings. Despite this cultural significance, hijras face substantial social stigma and discrimination, limiting their access to education, employment, and healthcare. They are often marginalized, and many resort to begging or sex work to survive, highlighting the gap between legal recognition and societal acceptance.

In Bangladesh and Pakistan, hijras are also acknowledged as a third gender. In Bangladesh, a landmark decision in 2013 granted them legal recognition, and they were included in the national census for the first time in 2021. Pakistan followed suit with similar recognition in 2009, and the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act was passed in 2018, providing comprehensive rights and protections. Despite these legal advances, hijras in both countries often face violence, social ostracism, and limited economic opportunities. They frequently encounter barriers in accessing public services, and societal attitudes still lag behind legal reforms.

Thailand is known for its relatively visible third-gender community, commonly referred to as kathoey or “ladyboys.” Kathoey are often prominent in the entertainment industry and are culturally recognized for their distinct identity. However, legal recognition remains ambiguous, and they often face challenges in official documentation, which can impact their access to various rights and services. Social acceptance is a double-edged sword; while kathoey may enjoy visibility and certain cultural freedoms, they also face significant discrimination and stereotyping, particularly outside urban centers.

In Samoa, the fa’afafine are an integral part of Samoan culture, embodying both masculine and feminine traits. Unlike in many other cultures, fa’afafine are generally accepted and integrated into Samoan society, participating fully in family and community life. This acceptance is rooted in traditional Samoan values, where fa’afafine play essential roles in the social and cultural fabric. However, the influence of Western norms and values has introduced some challenges to this acceptance, as modern Samoan society navigates the balance between traditional and contemporary views on gender.

Despite the varying degrees of recognition and acceptance, third-gender individuals in these and other countries often face challenges in achieving full equality. Legal recognition is a crucial step, but societal attitudes and systemic barriers continue to impede their ability to live free from discrimination and violence. Efforts to bridge this gap require comprehensive approaches that include legal reforms, public education, and the promotion of inclusive policies that respect and protect the rights of third-gender individuals.

- this term coincides with that higher and high income countries ↵

- Graf, Nikki, Anna Brown, and Eileen Patten. 2019. “The Narrowing, but Persistent, Gender Gap in Pay.” Fact Tank. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. ↵

- Omeokwe, Amara. 2020. “Women Overtake Men as Majority of U.S. Workforce.” Washington Post. January 10, 2020. ↵

- refers to the interconnected nature of social categories such as race, class, and gender, which create overlapping systems of discrimination or disadvantage. The goal of an intersectional analysis is to understand how different forms of discrimination, like racism, sexism, and homophobia for example, interact to shape our identities and experiences in society. ↵

- Heron, Melonie. 2018. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2016. National Vital Statistics Reports 67, no. 6. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics ↵

- National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. 2019. Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1a. National Inquiry, Canadian Government. ↵

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018. Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence in Australia, 2018. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. ↵