Chapter 12: Urban and Suburban Spaces

12.9 Challenges to the US City

12.9.1 The Federal Housing Administration (FHA)

The FHA, created in 1934 as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Depression-Era New Deal, was tasked with encouraging banks to make inexpensive loans to people seeking to buy new homes while ensuring that housing was built up to new safety standards. The FHA was part of a grand scheme to stimulate the housing sector of the economy during the Great Depression while extending federal oversight to the home loan industry. The program has worked. Overall homeownership was around 40% at the start of the Great Depression and it has been around 65% in recent years. The biggest jump in homeownership came shortly after World War II after the economy recovered and millions of veterans took advantage of the G.I Bill to help them secure a mortgage. However, the criteria upon which the government judged the desirability of insuring mortgage loans incentivized buying a new home in the suburbs, or rehabilitating old ones in the inner city. Faced with the option of buying a cheaper new home in a new suburban neighborhood or staying in the expensive, crowded inner-city, most people moved to the suburbs – if they could. Since many of those who qualified for loans were white and not in poverty, the FHA and related government programs helped increase the residential segregation of minorities by encouraging white flight from the cities. Minorities who were often poor and regularly prohibited from moving to new suburbs by discriminatory deed restrictions (see below), found themselves stuck in the city, where the FHA’s mortgage assistance programs were far less helpful.

12.9.2 Redlining

Source: “Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Philadelphia redlining map” from Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain.

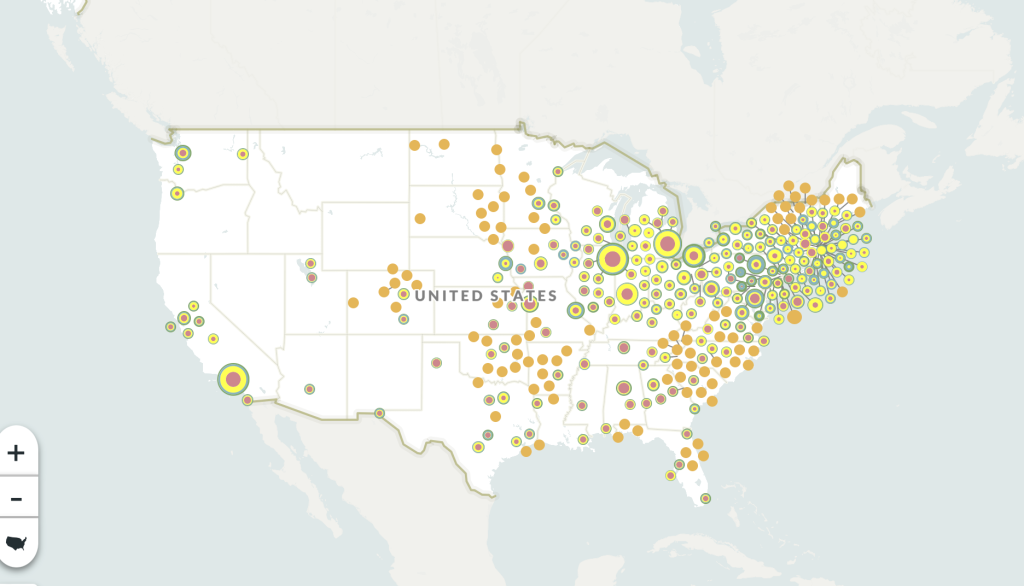

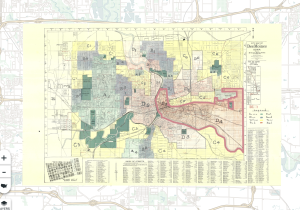

Redlining, a discriminatory practice that emerged in the 1930s, involved banks and insurers refusing loans or insurance to people living in certain areas, often based on racial or ethnic composition. This practice was institutionalized through maps created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) under the New Deal, which designated neighborhoods as high-risk based on their racial demographics. Areas with predominantly Neighborhoods with poor terrain, old buildings, or those threatened by “foreign-born, negro or lower grade population” were judged to be too risky for government help. These areas were marked in red, indicating high risk and effectively denying residents access to mortgages and investment. This systemic discrimination entrenched racial segregation and economic disparity, as minority communities were deprived of the opportunity to build wealth through homeownership. After the war, banks, insurance companies, and other financial institutions also mapped out where not to do business.

Source: A Screenshot of the Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America website.

Source: A screenshot of the Des Moines – redlining map.

The legacy of redlining contributed to the phenomenon of white flight, which intensified in the post-World War II era. In a practice called blockbusting, realtors would solicit white residents of the neighborhood to sell their homes under the guise that the neighborhood was “going downhill” because a black person or family had moved in. So, as desegregation policies slowly took hold and Black families began moving into previously all-white neighborhoods, white residents frequently relocated to suburban areas, taking advantage of newly built homes and federally subsidized highways. Blockbusting caused a substantial turnover in housing, benefiting real estate agents through the commissions they earned from representing both buyers and sellers. It also pushed landowners to sell their properties at low prices to quickly exit the neighborhood. This allowed developers to subdivide lots and construct tenements, which they typically neglected, leading to a further decline in property values.The resulting suburban expansion further deepened segregation, as urban centers were left with diminished tax bases and deteriorating infrastructure. Minorities faced still with racist deed restrictions in many new suburbs, found themselves stuck in the city. Meanwhile, the predominantly white suburbs enjoyed better-funded schools and services, perpetuating socio-economic divides that continue to impact American cities today.

Residents in neighborhoods with a “red line” drawn around them would not be able to get loans to buy, repair, or improve housing. Some could not get insurance on what they owned. If they could, the terms of the loan or the insurance rates were higher than those outside the zone; a practice called reverse redlining. The main criteria for inclusion in a redlined neighborhood were the percentage of minorities, thus most of the people who suffered from the ill-effects of redlining were minorities, notably African-Americans and Asians. Individuals with good credit histories and a middle-class income could find it impossible to buy homes in specific neighborhoods. Redlining was a death sentence to neighborhoods.

In 1968, the Fair Housing Act tried to outlaw redlining (and other forms of housing discrimination), but new laws were needed to bolster the language in the 1970s. However, by that time, long-term damage was evident in inner cities across the United States; once thriving neighborhoods turned into poor areas.. Although it is illegal to discriminate against minorities (or anyone really) for non-economic characteristics, there is ample evidence to suggest it still occurs.

12.9.3 Inner Cities and Urban Renewal

The development of inner cities in the United States can be traced back to the industrial revolution of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As industries flourished, urban areas rapidly expanded to accommodate factories and an influx of workers seeking employment. Immigrants and rural Americans flocked to cities, leading to densely populated neighborhoods and the construction of affordable housing. During this period, inner cities were bustling hubs of economic activity and cultural diversity. However, post-World War II suburbanization, facilitated by federal policies favoring home loans in suburban areas and the construction of interstate highways, led to a mass exodus of middle-class residents from urban centers. The departure of these residents, along with their tax contributions, left inner cities struggling with poverty, declining infrastructure, and inadequate public services.

As age and federal policies tore away at the fabric of America’s inner cities, the US government launched an effort known as

urban renewal in an attempt to reinvigorate the urban cores of large cities. The Federal Government launched several programs to provide funds to cities to buy up land in degraded parts of the city, to build public housing projects for the displaced, to bulldoze old neighborhoods, and to incentivize investors to rebuild on the vacated land. The idea was partly driven by a mistaken conviction that the visual elements of urban blight, were largely responsible for the problems of inner cities. Legislators believed that because old parts of cities were ugly, demolishing thousands of buildings would create a clean slate upon which new investment would pour in, and new businesses and housing would rise up. The displaced would be housed in new, high-rise housing projects that were clean and efficient. In a few instances, it worked. In some places, new businesses with good-paying jobs replaced abandoned old factories and warehouses. New apartments replaced dilapidated houses. Displaced folks moved to newer, cleaner safer housing elsewhere.

However, the failures of urban renewal appear to have outnumbered its successes by a wide margin. Frequently, thousands of residents, most of them poor and minority, were displaced from their homes and their neighborhoods only to be herded into overcrowded, poorly built public housing projects. Within a decade, the word “projects” became synonymous with segregation and crime (see the Ethnicity chapter for additional information). Urban redevelopment efforts often turned out to be driven by unscrupulous deals made between land developers and corrupt civic leaders, who funneled millions into projects that were unnecessary, half-completed or doomed to failure. Perhaps worst of all were the numerous cities that found themselves with acre upon acre of empty lots; untaxable wastelands with only sidewalks where neighborhoods once thrived. Some urban renewal neighborhoods were also dissected by new highways or other transportation corridors, effectively rending the social fabric of those communities and cutting off traffic to businesses that remained.

Source: “Pruitt-igoeUSGS02” by United States Geological Survey via Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain.

he Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St. Louis, Missouri, is a striking example of an urban renewal project gone wrong. Built in the mid-1950s, Pruitt-Igoe comprised 33 eleven-story buildings designed to provide affordable housing for low-income residents. However, the project quickly deteriorated due to poor design and maintenance. The high-rise buildings and large open spaces did not meet residents’ needs, leading to unsafe common areas and dilapidated conditions. High unemployment rates, inadequate social services, and the complex’s racial segregation—predominantly housing African Americans—further marginalized the community.

Government policies and insufficient funding exacerbated these issues. The federal government’s withdrawal of support for public housing in the late 1960s left Pruitt-Igoe in financial and operational limbo. By the early 1970s, the complex had become a symbol of the failures of urban renewal, plagued by crime and neglect. In 1972, just two decades after its construction, the decision was made to demolish Pruitt-Igoe. Its implosion highlighted the flaws of urban renewal strategies at the time, underscoring the necessity for comprehensive planning, sustainable design, and the integration of social services in urban development projects.

Gentrification: Today, many inner cities in the U.S. face significant challenges but also show signs of revitalization. Decades of disinvestment have resulted in persistent poverty, crime, and deteriorating infrastructure in some areas. As a way for city officials to deal with these inner-city problems, there has been a push to renovate inner-city areas, a process called gentrification. Middle-class families are drawn to city life because housing is cheaper, yet can be fixed up and improved, whereas suburban housing prices continue to rise. Some cities also offer tax breaks and affordable loans to families who move into the city to help pay for a renovation. Also, city houses tend to have more cultural style and design compared to quickly made suburban homes. Transportation tends to be cheaper and more convenient, so that commuters do not spend hours a day traveling to work. Couples without children and also retirees are drawn to city living because of the social aspects of theaters, clubs, restaurants, bars, and recreational facilities.

The logic behind gentrification is that it not only reduces crime and homelessness; it also brings tax revenue to cities to improve the city’s infrastructure. However, there has also been a backlash against gentrification because some view it as a tax break for the middle and upper class rather than spending much-needed money on social programs for low-income families. It could also be argued that improving lower-class households would also increase tax revenue because funding could go toward job skill training, childcare services, and reducing drug use and crime.

12.9.4 Homelessness

Homelessness is another primary concern for citizens of large cities. In January 2023, approximately one in every 500 Americans was homeless. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) recorded 653,104 homeless individuals in its annual point-in-time report, which assesses homelessness across the US on a single night each winter. This figure represents a 12.1% increase compared to the same report in 2022.

The total homeless population saw a steady decline from 2007 to 2022 before experiencing a 12.1% increase in 2023. The US Interagency Council on Homelessness attributes this recent rise to insufficient systems for affordable housing, wages, and equitable access to physical and mental healthcare, as well as economic opportunities. According to the council, individuals experiencing homelessness have a life expectancy of 50 years, significantly lower than the average American’s 77 years.

Who are the homeless? According to USAFacts, nearly 250,000 homeless Americans — 37.3% of the entire homeless population — identified as Black, African American, or African in 2023. By comparison, this demographic made up 13.6% of the US population in 2022.

There are multiple reasons why people become homeless. The Los Angeles Homeless Authority estimates that about one-third of the homeless have substance abuse problems, and another third are mentally ill. Nearly a quarter have a physical disability. A disturbing number are veterans of the armed forces or victims of domestic abuse. Economic conditions locally and nationally also have a significant impact on the overall number of homeless people in a particular year, not only because during recessions, people lose their jobs and homes, but because the stresses of poverty can worsen mental illness.

The government plays a significant role in the pattern and intensity of homelessness. Ronald Reagan is the politician most associated with the homeless crisis both nationally and in California. When Reagan became governor of California in the late 1960s, the deinstitutionalization of people with a mental health condition was already a state policy. Under his administration, state-run facilities for the care of mentally ill persons were closed and replaced by the for-profit board and care homes. The idea was that people should not be locked up by the state solely for being mentally ill and that government-run facilities could not match the quality and cost-efficiency of privately run boarding homes. Many private facilities, though, were severely run, profit-driven, located in poor neighborhoods, and had little professional staff. Patients could, and did, leave these facilities in large numbers, frequently becoming homeless or incarcerated. Other states followed California’s example. By the late 1970s, the federal government passed some legislation to address the growing crisis, but sweeping changes in governmental policy at the federal level during the Regan presidency shelved efforts started by the Carter administration. Drastic cuts to social programs during the 1980s ensured an explosion of mental illness related homelessness. Most funding has never been restored, though the Obama administration has aggressively pursued policies aimed at housing homeless veterans.

Though homeless people come from many types of neighborhoods, facilities for serving homeless populations are not well distributed throughout the urban regions. Many cities have a region known as Skid Row, a neighborhood unofficially reserved for the destitute. The term originated as a reference to Seattle’s lumber yard areas where workers used skids (wooden planks) to help them move logs to mills. Today, many of the shelters and services for the homeless are found in and around skid row.