Chapter 6: The Geography of Language

6.5 Multilingualism

Source: World Cloud by United States Census Bureau

No country in the world exclusively speaks one language. Practically, every country is multilingual, with multiple languages spoken. Officially, countries may designate a single official language (like Indonesia), acknowledge several official languages (like Canada and Switzerland), or choose not to declare any official language (like the United States). Countries with multiple official languages are referred to as multilingual states.

6.5.1 Multilingualism in Selected Countries

Multilingualism manifests differently across countries. In Canada and Switzerland, for instance, major languages are associated with specific provinces or regions. Canada recognizes French and English as equal federal official languages, with each province and territory having the autonomy to determine its official language(s). For example, Quebec designates French as its official language, while Nova Scotia uses English. Federal laws in Canada safeguard minority language speakers, ensuring education rights for native speakers of English in Quebec and French in Nova Scotia. Several provinces officially recognize both French and English, employing them in government and educational settings. Additionally, some Canadian provinces and territories, notably Nunavut, recognize and support Indigenous languages like Inuit.

Switzerland officially recognizes four national languages: German, French, Italian, and Romansh. German is the most widely spoken language, predominantly in the central and eastern regions. Romansh, a Romance language, is spoken by a small minority in the southeastern canton of Graubünden. Just like in Canada, Switzerland’s multilingualism is reflected in its federal structure. Each canton (region) has the authority to designate its official languages, leading to linguistic diversity across administrative boundaries. This linguistic diversity is supported by Switzerland’s federal government, which promotes multilingualism through education, media, and government services. As a result, Swiss residents often grow up learning multiple languages, contributing to a society where linguistic diversity is celebrated and multilingual proficiency is valued.

Another manifestation of multilingualism blends the language of a colonizing power with a local or regional language as an official means of communication. In India, British colonization entrenched English in education and government. Selecting English as an official language recognized its widespread use among the educated and politically influential elite. During colonization, the British encouraged academically talented Indians to pursue higher education in England to gain fluency in English, as well as exposure to Western ideas and disciplines. Upon gaining independence, India established parliamentary governance akin to that of its colonizers and adopted English alongside Hindi as an official language. At the time, Hindi was the primary language for 26% of Indians and currently is spoken by 44% of the population. This decision to elevate a major indigenous language not spoken by the majority has led to tensions.

Despite being colonized by France and Spain, Morocco opted not to adopt the languages of its colonizers upon gaining independence. Instead, the country designated Standard Arabic, the predominant language spoken, and in 2016 Moroccan Berber, the indigenous language of the region prior to Arab conquest, as its official languages. French, which is commonly taught as a third language, remains influential but holds a secondary status. Moroccan children typically learn Arabic as their first language, followed by Berber, and then French, necessitating proficiency in three languages and three different alphabets during their schooling.

6.5.2 Multilingualism in the United States

Language diversity existed in what is now the United States long before the arrival of the Europeans.

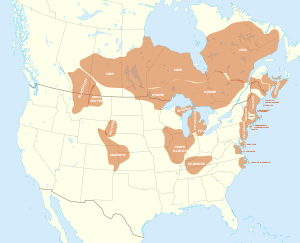

Source: “Early Localization Native Americans USA.jpg” by William C. Sturtevant, Smithsonian Institute, 1967 via Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain.

It is estimated that there were between 500 and 1,000 Native American languages spoken around the fifteenth century and that there was widespread language contact and bilingualism among the Indian nations. Here is a map showing the distribution of the many indigenous languages in the US. Figure 6. shows the distribution of the Algonquian languages (a language branch that was also present in Virginia). The Eastern Algonquian languages constitute a subgroup of the Algonquian languages.

Source: “Algonquian language map with states and provinces.svg” by Noahedits via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Prior to European contact, Eastern Algonquian consisted of at least 17 languages, whose speakers collectively occupied the Atlantic coast of North America and adjacent inland areas, from what are now the Maitimes tof Canada to North Carolina.

With the arrival of the Europeans, seven colonial languages established themselves in different regions of the territory:

- English along the Eastern seaboard, Atlantic coast

- Spanish in the South from Florida to California

- French in Louisiana and northern Maine

- German in Pennsylvania

- Dutch in New York (New Amsterdam)

- Swedish in Delaware

- Russian in Alaska

Dutch, Swedish and Russian survived only for a short period, but the other four languages continue to be spoken to the present day. In the 1920’s, six major minority languages were spoken in significant numbers partly to due to massive immigration and territorial histories. The “big six” minority languages of the 1940’s include German, Italian, Polish, Yiddish, Spanish and French. Of the six minority languages, only Spanish and French have shown any gains over time, Spanish because of continued immigration and French because of increased “language consciousness” among individuals from Louisiana and Franco-Americans in the Northeast.

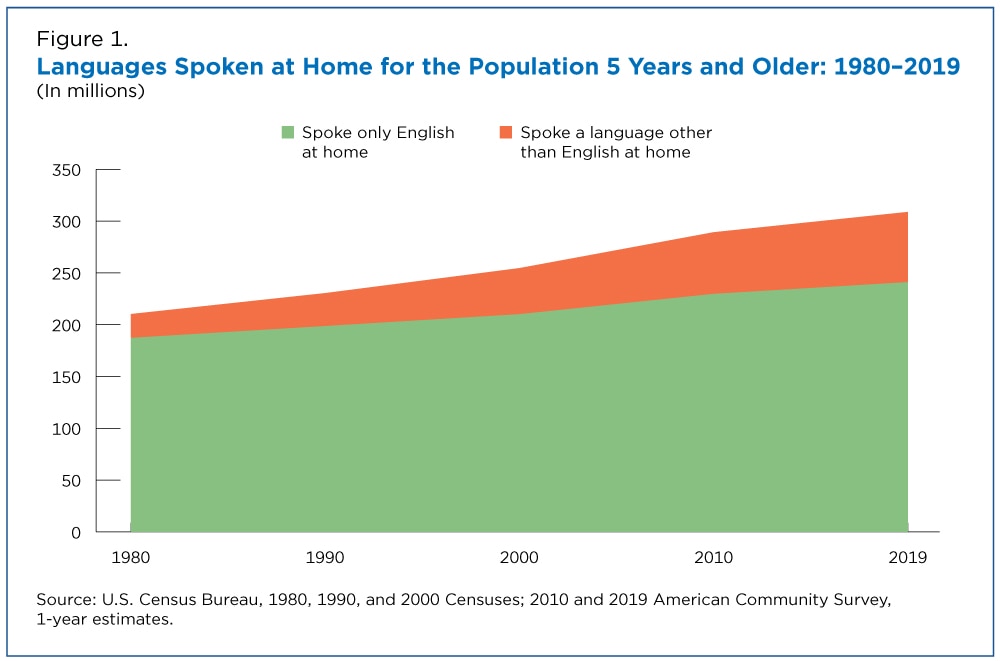

Source: “Figure 1: Languages Spoken at Home for the Population 5 Years and Older: 1980-2019” by Sandy Dietrich and Erik Hernandez via United States Census Bureau.

In 2019, nearly 68 million people spoke a language other than English at home. According to a recent U.S. Census Bureau report the number of people in the United States who spoke a language other than English at home nearly tripled from 23.1 million in 1980 to 67.8 million ) in 2019; at the same time the number of English-only speakers also increased considerably.

Source: “Languages cp-02.svg” by Datavizzer via Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

6.5.3 The Benefits of Multilingualism

While 92% of primary and secondary students in Europe learn a foreign language, only 20% of their counterparts in the U.S. do so. This disparity is not surprising given that Europe consists of many different countries, each with its own language, necessitating the need for learning multiple languages. In contrast, the United States is a large landmass that primarily borders only two countries: Canada, where English and French are spoken, and Mexico. However, in an increasingly globalized world, it would be beneficial for everyone to speak a second language. Although there is debate over the benefits of foreign language education, many agree that bilingualism enhances communication with diverse populations and provides job market advantages. Research from Concordia University highlights an additional benefit: cognitive advantages. Evidence suggests that bilingual individuals exhibit superior inhibitory control, allowing them to ignore irrelevant information during tasks. For example, a 2015 study using the Stroop test found that bilinguals outperformed monolinguals when the color and word did not match, demonstrating less distraction by irrelevant information. Additionally, bilinguals are better at managing complex tasks and switching attention to relevant goals.

One of the most significant findings is that bilingualism may delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, which is characterized by progressive memory loss and cognitive decline. Studies[1] have shown that bilingual Alzheimer’s patients experience a delay of 4-5 years in the onset of symptoms compared to monolingual patients, regardless of sex, lifestyle, education, and occupation. This delay is linked to thicker and denser brain regions associated with language and cognitive control in bilingual individuals. These brain characteristics help patients maintain some memory function, particularly in recalling autobiographical events. However, whether bilingualism directly causes the delay in Alzheimer’s onset remains to be conclusively determined.

- Hilary D. Duncan, Jim Nikelski, Randi Pilon, Jason Steffener, Howard Chertkow, Natalie A. Phillips, Structural brain differences between monolingual and multilingual patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease: Evidence for cognitive reserve, Neuropsychologia, Volume 109, 2018, Pages 270-282, ISSN 0028-3932, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.12.036. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0028393217305109) ↵