Chapter 14: The Humanized Environment

14.4 Nature Consumerism – Tourism

14.4.1 Impact of Transportation

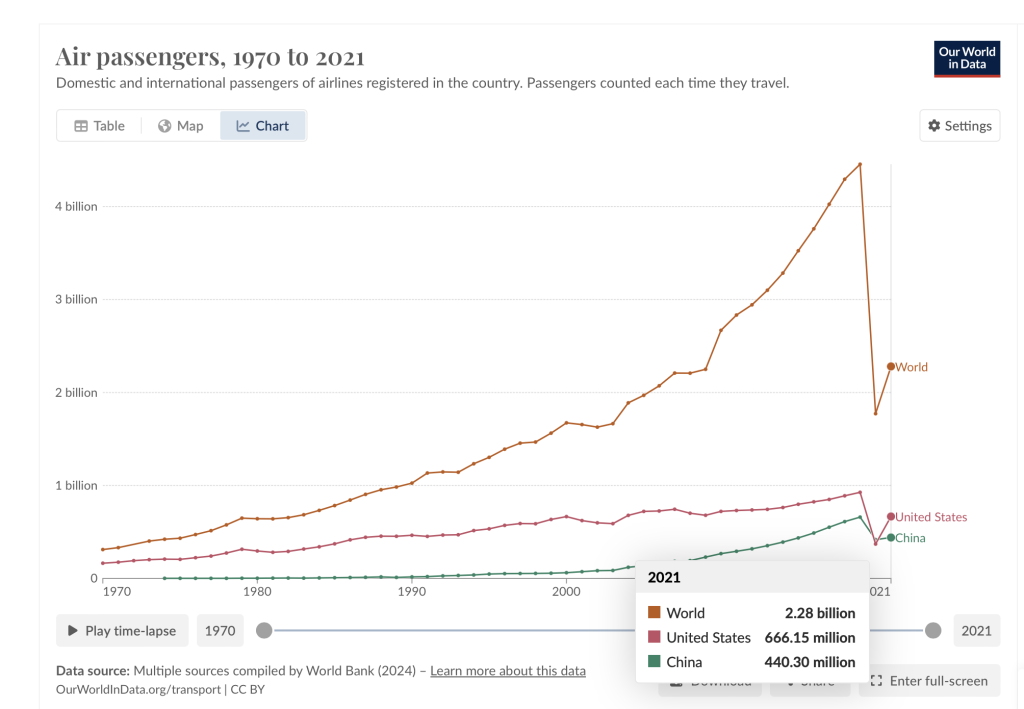

Large-scale tourism relies heavily on mass transportation, particularly air travel. Although aircraft are now twice as fuel-efficient as they were four decades ago, air travel has increased tenfold in that time (see Figure 14.4.1). In addition, the graph depicting air freight in tonne kilometers looks very similar to Figure 14.4.1. In 2010, over 5 billion Revenue Passenger Kilometers were recorded, and this figure is expected to rise to 40 billion by 2042 (International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), 2016).Despite improvements in fuel efficiency and quieter engines, these aircraft still emit significant amounts of nitrous oxides and carbon dioxide into the upper atmosphere.

Source: “Wonder of the Seas” by Jörg Fuhrmann via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

As of November 2022 there were 302 cruise ships operating worldwide (in 2023 there were 450 cruise ships but not all were on the oceans at the same time), with a combined capacity of 664,602 passengers. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that, apart from the daily fuel burn, an average cruise ship with 3000 passengers generates some 21,000 gallons of sewage each day – not all of it properly disposed of; i.e. it is often dumped into the seas.

While congestion is the more noticeable issue resulting from the increase in vehicles at popular tourist destinations, the concentration of exhaust gases in both urban and rural areas can significantly impact the health of tourists and residents. The unchecked rise of private vehicles in major tourist cities like Bangkok can degrade the visitor experience to the extent that it deters people from traveling to or staying in the city.

The popularity of off-roading with SUVs and ATVs is also damaging to the environment in sensitive areas of the world. This sport is popular among American tourists, and some wilderness areas are now under threat, particularly in Utah. Moab, south-east of Salt Lake City, has attracted significant numbers of such vehicles, as have sand dunes in several parts of the world, where these vehicles can destroy sparse scrubland and erode the landscape.In upstate New York, certain state parks initially permitted the use of ATVs but later reversed their decision and banned them.

14.4.2 Visual Blight

Scenic areas attract large numbers of tourists, leading to the loss of natural landscapes due to the development of hotels and other amenities to meet tourist demands. As a result, these areas eventually lose their scenic appeal, causing tourists to seek out more tranquil and beautiful destinations. Similarly, without careful management, stately homes may expand visitor facilities—such as larger car parks, cafés, shops, signposts, and toilets—diminishing the main attraction’s charm. In extreme cases, like in the USA, excessive signage and advertising can spoil both rural and urban landscapes, though some may argue that illuminated signs in places like Reno and Las Vegas add to the appeal. Additionally, visual pollution from poorly designed tourist buildings is common, often due to a lack of planning control. Developers favor cheap, high-rise hotels that clash with the local architecture, resulting in unattractive structures. This trend is evident in seaside resorts worldwide, where concrete skyscraper hotels, from Waikiki in Hawaii to Benidorm in Spain, disregard the cultural and traditional aesthetics of their locations.

Other common forms of visual pollution by tourists include littering. In environmentally sensitive areas like wilderness regions, littering is a major issue due to the lack of nearby public services. Tourists must take responsibility for their waste. This problem is prominent in the Himalayas, where the popularity of trekking has led to litter and human waste accumulating in some valleys, with trash decomposing slowly at high altitudes. Environmentalists and responsible tour operators urge visitors to burn or carry out their rubbish and bury human waste, though local villagers often repurpose left-behind tins, bags, and bottles.

Another type of pollution that affects fauna and flora tremendously is that of light pollution at night.

Source: “City Lights 2012 – Flat map crop” by NASA Earth Observatory is in the public domain in the United States.

1.4.4.3 Carrying Capacity

One of the most obvious problems caused by mass tourism is congestion-overcrowding of the natural environment. Recognizing that the number of tourists an area can accommodate is limited has led to the concept of carrying capacities—the maximum number of people an area can sustain before the damage becomes irreversible. Parking lots, streets, beaches, ski slopes, cathedrals, camping sites and similar areas have a finite limit to the number of tourists they can accommodate at any time. Theoretically, this also applies to entire regions and countries, although defining a city’s or country’s tourist capacity is rarely attempted. Most national tourist offices aim to increase tourist numbers annually with little consideration for the area’s ability to handle them. Some efforts may be made to divert tourists to off-peak times or less crowded areas. A few cities under extreme pressure, like Florence and Venice, have taken steps to control tourist numbers, including limiting access, which can lead to visitor disappointment.

The rapid increase in mega-ship arrivals at popular coastal destinations has made site management crucial. Dubrovnik, a key port for these ships, can see four or more vessels daily, with over 12,000 passengers flooding its narrow streets, leading to shoulder-to-shoulder congestion as pedestrians navigate shops and restaurants. Similarly, Venice faces massive congestion in its main shopping streets due to the influx of cruise visitors. Barcelona, Spain, saw 10 cruise ships per day during the peak season coming into the city center before the decisions was made to limit the number of ships to 7/day and for the cruise ships to dock 30 minutes away. Nevertheless, the recent uproar of the population of Barcelona as a response to ‘Overtourism’ gives insight to local residents suffering.

Source: “TheWave 1600pixels” by Gb11111 via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC0 1.0.

In wilderness areas, the psychological capacity of the region is often very low, and even a relatively small number of visitors can cause significant environmental damage. In the USA, both Yellowstone and the Everglades National Parks are under severe physical threat from tourism. Psychologically, their remoteness means that any influx of mass tourism significantly diminishes their appeal. An extreme example of this is The Wave. The Wave, a remote rock feature in the USA, requires a 3-mile trek across the Colorado Plateau desert. It attracts photographers worldwide, but due to its sensitivity, only 20 visitors daily gain access. Ten are chosen months ahead via a US Bureau of Land Management lottery, while the remaining ten are selected on-site daily at 9am through another lottery.

The behaviour of tourists at wilderness sites will be a factor in deciding their psychological capacity. Many visitors to an isolated area will tend to stay close to their cars, so hikers who are prepared to walk a mile or so away from the car park will readily find the solitude they seek.

The ecological capacity to accommodate tourists is crucial. In urban areas, excessive tourism can diminish its appeal, though environmental impact in the short term is typically limited. Conversely, in rural or delicate environments, excessive tourism can disrupt natural balance, as evident in African safari parks where high vehicle densities during ‘big five’ hunts resemble car rallies, posing significant challenges.

Tourism in Sensitive Areas

In ecologically sensitive areas, such as the Galapagos Islands, Costa Rica, and Belize, tourism development was initially controlled, and efforts were and are made to ensure visitors respect the natural environment. Especially Costa Rica became quite known for its thoughtfully worked out ecotourism brand that attracted people who’d want to leave little trace.

Source: “Iguanamarina” by Marc Figueras via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Marine iguana.However, the demand is difficult to resist due to the significant economic benefits for lower income countries. For example, in 1974, authorities of the Galápagos Islands set a target of 12,000 visits to the Galapagos (later revised to 40,000), but the number of visitors now reaches around 225,000 annually, effectively abolishing the limit. The growing tourism industry has attracted residents, mostly from mainland Ecuador, increasing the population from 5,000 in the 1960s to over 25,000 today. Despite tourism contributing nearly $100 million to the economy, poverty remains a significant issue for many island residents.

14.4.4 Erosion

Certain sites are exceptionally delicate. In the USA, sand dunes have suffered destruction and erosion from beach buggies and four-wheel drive vehicles. Similarly, in the UK, motorcycle rallying poses threats by disturbing crucial dune grass clumps that support entire ecosystems. According to a report from the European Environment Agency in 2001, three-quarters of Mediterranean coastline sand dunes from Spain to Sicily have vanished due to tourism expansion.

Preservation Effort: La Dune du Pilat, FR

Source: “DunePyla2” by Mtu33260 via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Aerial view of the Dune of PilatLocated on the Atlantic coast of southwest France, this sand dune is Europe’s largest, standing over 100 meters tall and stretching 500 meters wide along 2.7 kilometers of coastline. Continuously shaped by wind and tides, the dune steadily advances inland by several meters each year, causing erosion of nearby pine forests and engulfing adjacent camping sites.

Source: “Paragliding Dune de Pilat” by Dennis Buntrock via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Recent infrastructure improvements, such as expanded highways, larger car parks, and a new visitor center, have facilitated easier access to the site. Consequently, over a million visitors annually flock to witness and ascend the dune. Recognizing the physical challenge of scaling its height, especially for less agile tourists, site managers have installed a staircase to assist in reaching the summit.

While constructed sites are generally more resilient than natural ones, they too can undergo erosion over time—externally from weather and internally from the wear and tear caused by numerous visitors. For instance, to preserve the ancient buildings, parts of the Acropolis in Athens have been restricted from tourist access. Similarly, popular attractions like Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon face challenges with the deterioration of wooden floors and staircases due to the high volume of annual visitors. Despite Stratford’s modest population of 26,000, it attracts 4.9 million visitors annually, many of whom seek out Shakespeare’s birthplace.

14.4.5 Impact on Flora and Fauna

Wildlife often serves as a major draw for tourists in various destinations. For example, the Great Barrier Reef in Australia attracts snorkelers and scuba divers eager to witness its diverse marine life, while African safaris appeal to those seeking encounters with large game animals. However, tourism can pose significant threats to the very wildlife it promotes.

Firstly, the construction of tourist infrastructure such as hotels, restaurants, and visitor centers can encroach on wildlife habitats. Fences around developments may disrupt traditional grazing or migration routes and divert essential resources like water from rivers and watering holes. Improper waste management can also lead to wildlife scavenging on leftover food and potentially harmful items like plastic packaging and camera batteries. Noise from construction activities can disturb nesting grounds and scare away wildlife.

Even when tourist facilities are not directly adjacent to wildlife habitats, frequent visits by tourists can disrupt breeding patterns, foraging behaviors, and natural responses to human presence. This disturbance has been observed affecting loggerhead turtles in regions like Greece, Turkey, and the Caribbean, where bright lights from tourist resorts can distract them from nesting and egg-laying activities.

Careful management is essential to mitigate these impacts and ensure sustainable coexistence between tourism and wildlife conservation efforts.

Tourism in Antarctica

Source: “Kaiserpinguine mit Jungen” by Giuseppe Zibordi via Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain.

Antarctica stands alone as a place unlike any other on Earth, more comparable to the moon or an uncontacted tribe than a crowded national park. Its wildness and profound silence make it truly extraordinary, drawing visitors not just to observe its wildlife, but also to experience a sense of adventure.

The Antarctic continent has increasingly become a destination for mass tourism, with cruise ships capable of accommodating up to 600 passengers regularly visiting the peninsula. Ice-breakers designed for passenger transport also reach as far south as Scott’s and Shackleton’s bases. Visitor numbers to Antarctica were modest in the past, with 6,704 in 1992, rising to 12,109 in 2001, and peaking at over 45,000 in 2007. Subsequent years saw annual numbers drop to around 35,000, but in recent years, they have surged past 50,000. For the 2023-2024 season the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operations (IAATO) reports over 80,000 landed visits and over 43,000 visitors remaining on the cruise ships[1].

While some visitors only fly over the continent, often to reach the South Pole, the majority (between 75% and 85%) land to participate in sightseeing or adventure activities such as seal and penguin watching, overnight camping, cross-country skiing, or kayaking.The popularity of vast penguin colonies, possibly influenced by the film “March of the Penguins,” has led to some colonies receiving up to three visits daily. This frequent human presence has affected the behavior and breeding patterns of these birds.

Antarctic seabirds also face challenges due to the presence of the many tourist ships in the region. Birds, particularly prions and petrels, are known to land on ships in the Southern Ocean and struggle to take off again because their legs are not adapted for walking.This behavior is exacerbated by ship lights that disorient the birds, worsened by adverse weather conditions like fog and snow. To mitigate these impacts, the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators has implemented protocols for ship crews to minimize disturbances to seabirds.

- https://iaato.org/information-resources/data-statistics/ ↵