Chapter 12: Urban and Suburban Spaces

12.7 Megacities

Source: “Goal 11 Logo” from the Sustainable Development Goals – Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

This chapter aligns with the UN’s 11th Sustainable Development Goal, which aims to create cities and human settlements that are inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

12.7.1 How do we Define Megacities?

According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs in its 2018 “World Urbanization Prospects” report megacities are urban agglomerations with over 10 million inhabitants. Another term often used to describe this is conurbation, a somewhat more comprehensive label that incorporates agglomeration areas such as the Rhine-Ruhr region in Germany’s west which has 11.9 million inhabitants (part of the ‘Blue Banana’ discussed in Chapter 12.6). Of the 30 biggest megacities worldwide, 20 of them are in Asia and South America alone, including Baghdad, Bangkok, Buenos Aires, Delhi, Dhaka, Istanbul, Jakarta, Karachi, Kolkata, Manila, Mexico City, Mumbai, Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto, Rip de Janeiro, Sao Paulo, Seoul, Shanghai, Teheran, and Tokyo-Yokohama. European megacities include London and Paris, and the UN estimates that the number of megacities worldwide will only increase as discussed in Chapter 12.5.

Source: “Percentage urban and urban agglomerations by size class map” by United Nations, DESA, Population Division is licensed under CC BY 3.0 IGO.

The explosive growth of these and other cities is a result of industrialization and better employment opportunities in cities than in rural areas. In addition, climate change is increasingly becoming a key driver of rural-to-urban migration around the world. As temperatures rise, rural areas are more vulnerable to extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, and storms, which can devastate agricultural productivity—the backbone of many rural economies. For instance, prolonged droughts can lead to water scarcity and crop failure, directly affecting the livelihoods of farmers and those dependent on agriculture. Similarly, rising sea levels and coastal erosion can destroy homes and farmland, making traditional rural living unsustainable. In regions like Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Central America, these climate-induced challenges force people to migrate to urban areas in search of better economic opportunities, more stable living conditions, and access to essential services like healthcare and education. This rural-to-urban migration, however, poses new challenges for both the migrants and the cities they move to.

The megacities of the world differ not only according to whether they lie in the southern or northern hemisphere, but also by country, climatic and political conditions. Megacities can be rich, poor, organized or chaotic. Paris and London are megacities, but it’s difficult to compare them demographically or economically with Jakarta or Lagos. Rich megacities tend to stretch out further than their poorer counterparts: Los Angeles’ settlement area is four times as big as Mumbai’s despite its population being smaller. Rich city inhabitants have a much higher rate of land consumption for apartments, transport, business, and industry. The situation is similar in terms of water and energy consumption, which is much higher in affluent cities. Cairo and Dhaka are without doubt ‘monster cities’ in terms of their population size, spatial and urban planning. But they are also “resourceful cities,” home to millions of people with few resources.

12.7.2 Environmental Concerns for Megacities

The high population levels in megacities and mega urban spaces are leading to a host of problems such as guaranteeing all residents a supply of basic foods, drinking water and electricity. Related to this are concerns about sanitation and disposal of sewage and waste. There isn’t enough living space for incoming residents, leading to an increase in informal settlements and slums. Many urban residents get around via bus, truck or motorized bicycles, leading to chaos on the streets and CO2 emissions leaking into the air.

Source: “Favela-Nova Friburgo” by Nate Cull via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

The faster a city develops, the more critical these issues become. Due to their rapid growth, megacities in developing countries and in the southern hemisphere have to battle in order to provide for their inhabitants. Between 1950 and 2000, cities in the north have grown an average of 2.4 times. In the south they’ve grown more than 7-fold over the same period. Lack of financial resources and sparse coordination between stakeholders at different levels intensify the problems. Megacities usually do not represent one political-administrative unit, instead dividing the city into parts such as with Mexico City, which is made up of one primary core district (Distrito Federal) and more than 20 outlying municipalities (municípios conurbados) where differing planning, construction, tax and environmental laws are carried out than in the core district.

Two key causes behind city growth are high rates of immigration as well as growing birth numbers. People move to the city with the hope of a more prosperous life and leave the country in search of brighter prospects. Without careful planning and infrastructure in place, this road can often lead to another poverty trap. As cities grow, so too do the unplanned and underserved areas, the so-called slums. In some regions of the world, more than 50 percent of urban populations live in slums. In parts of Africa south of the Sahara, that number jumps to around 70 percent. In 2007, a reported one billion people lived in slums and by 2024, that figure grew to 1.1 billion, according to the UN with 2 billion more expected in the next 30 years.

12.7.2.1 Slums and Gated Communities

The UN defines slums as overcrowded, poor, informal forms of housing that lack reasonable access to clean drinking water and sanitary facilities and deprive residents of power of the land. Above all, slums are a structural and spatial expression of lack of housing and growing urban poverty. . The well-known symbols of this are makeshift huts, such as the favelas in Brazil, but also desolate and overcrowded apartment buildings in major Chinese cities where the growing army of migrant workers and workers find makeshift accommodation. A shanty town, also known as a squatter, is a slum settlement that usually consists of building material made from plywood sheets of plastic, cardboard boxes, and other cheap material. They are usually found on the periphery of cities or near rivers

Source: “Principaux Bidonvilles” by Walké via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Check this video for a great view into Brazil’s slums – favelas.

The reasons so many of the residents in these cities are poor is due to underemployment and insufficient pay as well as low productivity within the informal sector. Around half the people in megacities that lie in the southern hemisphere are employed in the informal sector, many of whom are coerced into accepting any kind of employment. They sell various products – cigarettes, drinks, food, bits and pieces – simple services like shoe cleaning and letter writing as well as smuggling goods or ending up in prostitution. Exploitation is at times rife in slum settings due to insecure residences, lack of legal protection, poor sanitation and unstable acquisition conditions.

This video provides some snapshots of life in a slum or slum-like conditions:

Parallel to the growth of slums, gated communities – or exclusive neighborhoods – are also on the rise. These are fenced and well-monitored communities in which affluent members live, further driving the trend towards separation among urban populations.

But it’s not just living spaces splitting the cities – globally, there is a major push towards big new building projects like über-modern banks and business districts which stand in stark contrast to informal areas for the poor. These central business districts (CBD) are often siloed off from the main part of the city and migrate, along with the gated communities, towards the outskirts of town as is the case in Pudong, Shanghai and Beijing. For the most part, urban planning is based on the needs of the consumer and culture-oriented upper classes and economic growth sectors with the result being that the gap between rich and poor continues to grow. Such fragmented cities are a fragile entity in which conflicts are inevitable.

12.7.2.2 Addressing Overcrowding Problems

Urban residents the world over require good air to breathe, clean drinking water, access to proper healthcare, sanitary facilities and a reliable energy supply. The current situation in cities in developing countries can be precarious: the air is thick enough to touch; sewage treatment plants, if any, are overloaded and industrial factories secrete virtually unregulated highly toxic waste and wastewater. In addition, climate change will likely hit poorer cities harder.

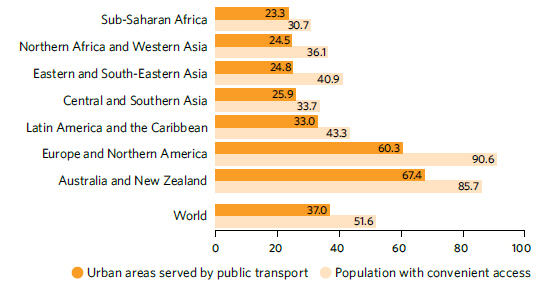

Source: “Coverage of public transport and share of population with convenient access in urban areas, 2022 (percentage)” by United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Considering the fact that most people on the planet are city-dwellers, we need to look at developing and designing urbanization and urban migration in a sustainable way. Since the root problem is poverty and pollution, the UN looks for better public transportation as one key focus as “in 2022, only half of the world’s urban population had convenient access to public transportation. Urban sprawl, air pollution and limited open public spaces persist in cities.” 1 According to UN statistics, people in developed countries, generally have multiple transportation options, though these are not always distributed equitably or with environmental considerations in mind. Conversely, in developing nations, where around 1 billion people still lack access to all-weather roads, the need for mobility for both people and goods is growing rapidly each year. Data from 2022 indicate that only 51.6 percent of the global urban population has convenient access to public transport, with significant regional disparities.

Bolivia Leading the Way at Innovative Means of Transportation

Source: “Mi Teleférico – Linea Naranja” by Adelina Herbas via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Bolivia addressed the public transportation problem by investing heavily into a cable car system, known as Mi Teleférico. It soars above the city, providing a unique and efficient mode of transportation that connects La Paz with El Alto and other urban areas. Overall, this system stretches over 32 km and has 38 stations. Launched in 2014, this extensive network has transformed the daily commute for thousands of residents. The cable cars glide over the rugged Andean terrain significantly reducing travel time. What once took hours on congested roads can now be traversed relatively quickly, making the system not only a marvel of engineering but also a vital component of urban mobility.

One major drawback to such an installation is the high cost of construction and maintenance, which can strain public finances. The initial investment required for such infrastructure is substantial, and ongoing operational expenses can be significant, potentially diverting funds from other critical public services. Other concerns include issues of accessibility, as the system may not be affordable for all residents due to fare costs. Additionally, the coverage may be limited, and there may be physical accessibility challenges for the elderly and disabled. Furthermore, the cable cars do not address the broader transportation needs of the entire city, particularly in areas not serviced by the system.

The success of Mi Teleférico has inspired similar projects demonstrating the potential of cable cars to address urban transportation challenges:

- Medellín, Colombia: The Metrocable system in Medellín was one of the first urban cable car projects aimed at improving transportation in hilly areas. It has significantly enhanced connectivity for residents in impoverished neighborhoods, integrating seamlessly with the city’s metro system.

- Caracas, Venezuela: The Metrocable system in Caracas connects the hillside barrios to the city center, providing residents with a safer and more efficient mode of transportation. This system has been instrumental in reducing travel times and improving access to essential services.

- Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: The Complexo do Alemão cable car system was built to serve the residents of the favelas, offering a quick and reliable transportation option over difficult terrain. Although the system has faced operational challenges, it remains a critical part of the city’s transport network. This system was suspended because of lack of funding.

- Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: The Teleférico da Providência in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, was designed to improve transportation for residents of the Providência favela, connecting the hilltop community to the central railway station Central do Brasil. Opened in 2014, it aimed to reduce travel time and provide a reliable transportation option. However, the system faced criticisms regarding maintenance, operational reliability, and actual usage by residents. Consequently, it was closed for several years. After being shut down for around seven years, the cable car system was reopened in 2023, with renewed efforts to address its previous shortcomings and better serve the community’s needs.

-

Figure 12.7.7 Cablebus in Mexico City (Click the image to see it on Wikimedia.)

Source: “Inauguración Tlalpexco-Campos Revolución (60417cb7b69fc936233884)” by Jefatura de Gobierno de la Ciudad de México / Gobierno de la Ciudad de México via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 4.0.Mexico City, Mexico: The Cablebús system in Mexico City, inaugurated in 2021, aims to connect underserved areas with the rest of the city. It reduces commute times and provides a more comfortable and scenic alternative to traditional road transport.

- Toulouse, France: The Téléo cable car system in Toulouse is one of Europe’s longest urban cable car lines. It connects different parts of the city, including a university campus and medical centers, providing a sustainable and efficient transport solution. The system became operational in 2022. Here is an article on the subject.

On an international level, there are countless efforts currently being undertaken to support sustainable urban development. A number of large UN projects, such as the UN-HABITAT-Program, Sustainable Urban Development Network (SUD-Net) or the Urban Management Program (UMP), are endeavoring to improve and strengthen governmental and planning abilities. One of the goals of the UMP is to also implement the Sustainable Development Goals at the city level. Many urban problems can be explained not only at the city level, but must be regarded as results of political disorder and economic instability on a global and national level – and that this is where the solutions lie.