Chapter 12: Urban and Suburban Spaces

12.4 The Evolution of Cities

12.4.1 Urban Origins

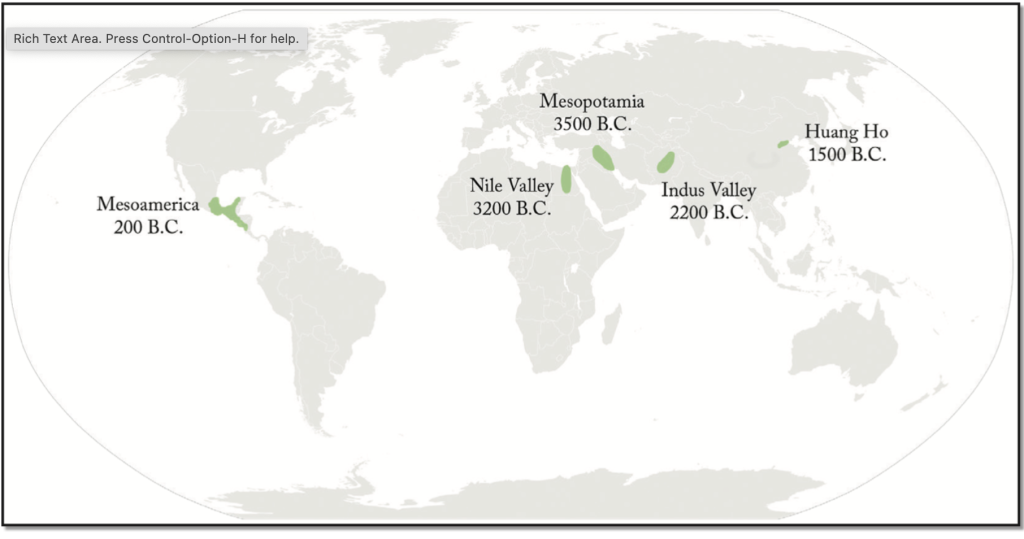

Source: “Five Hearths of Urbanization” by “Canuckguy” and Corey Parson via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The earliest towns and cities developed independently in the various regions of the world. These hearth areas have experienced their first agricultural revolution, characterized by the transition from hunting and gathering to agricultural food production. Five world regions are considered as hearth areas, providing the earliest evidence for urbanization: Mesopotamia and Egypt (both parts of the Fertile Crescent of Southwest Asia), the Indus Valley, Northern China, and Mesoamerica as you can see in Figure 12.4.1. Over time, these five hearths produced successive generations of urbanized world-empires, followed by the diffusion of urbanization to the rest of the world.

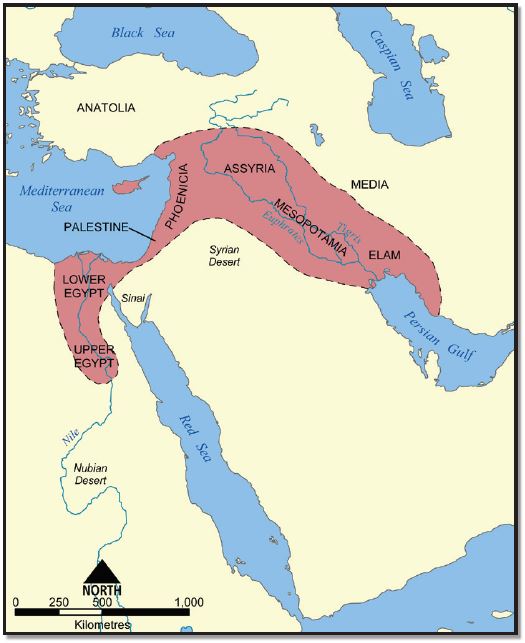

Source: “Fertile Crescent” by NormanEinstein via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

The first regions of independent urbanism were in Mesopotamia and Egypt from around 3500 B.C. Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, was the eastern part of the so-called Fertile Crescent (Figure 12.4.2). From the Mesopotamian Basin, the Fertile Crescent stretched in an arc across the northern part of the Syrian Desert as far west as Egypt, in the Nile Valley. In Mesopotamia, the significant growth in size of some of the agricultural villages formed the basis for the large fortified citystates of the Sumerian Empire such as Ur, Uruk, Eridu, and Erbil, in present-day Iraq. By 1885 B.C., the Sumerian city-states had been taken over by the Babylonians, who governed the region from Babylon, their capital city. Unlike in Mesopotamia, internal peace in Egypt determined no need for any defensive fortification. Around 3000 B.C. the largest Egyptian city was probably Memphis (over 30,000 inhabitants). Yet, between 2000 and 1400 B.C., urbanization continued with the founding of several capital cities such as Thebes and Tanis.

Source: “SSA41434” by BrCG2007 via Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain.

About 2500 B.C, large urban settlements were developed in the Indus Valley (Mohenjo-Daro, especially), in modern Pakistan, and later, about 1800 B.C., in the fertile plains of the Huang He River (or Yellow River) in Northern China, supported by the fertile soils and extensive irrigation systems. Other areas of independent urbanism include Mesoamerica (Zapotec and Mayan civilizations, in Mexico) from around 100 B.C. and, later, Andean America from around A.D. 800 (Inca Empire, from northern Ecuador to central Chile). Teotihuacan (12.4.3), near modern Mexico City, reached its height with about 200,000 inhabitants between A.D. 300 and 700.

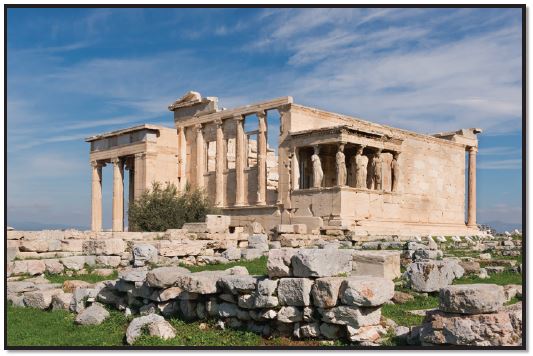

Source: “Erechtheum Acropolis Athens” by Jebulon via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC0 1.0.

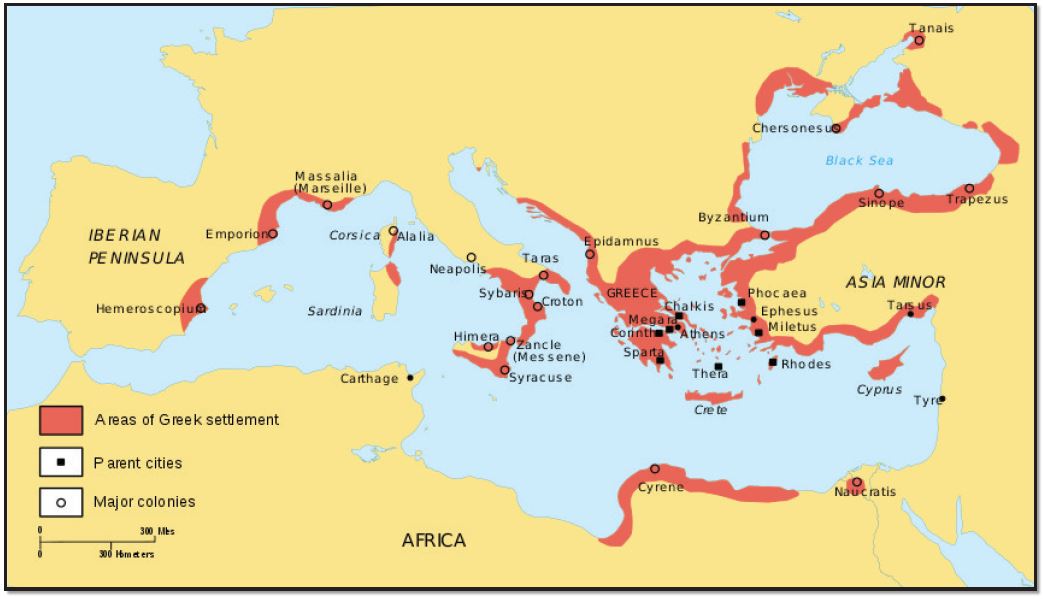

The city-building ideas eventually spread into the Mediterranean area from the Fertile Crescent. In Europe, the urban system was introduced by the Greeks, who, by 800 B.C., founded famous cities such as Athens, Sparta, and Corinth. The city’s center, the “acropolis,” visible in Figure 12.4.4 was the defensive stronghold, surrounded by the “agora” suburbs, all surrounded by a defensive wall. Except for Athens, with approximately 150,000 inhabitants, the other Greek cities were quite small by today’s standards (10,000-15,000 inhabitants). The Greek urban system, through overseas colonization, stretched from the Aegean Sea to the Black Sea, around the Adriatic Sea, and continued to the west until Spain (see the map in Figure 12.4.5). Although the Macedonians conquered Greece during the 4th century BC, Alexander the Great extended the Greek urban system eastward toward Central Asia. The location of the cities along Mediterranean coastlines reflects the importance of long-distance sea trade for this urban civilization.

Source: “Greek Colonization Archaic Period” by Dipa1965 via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Source: “Romancoloniae” by Cresthaven via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

With the impressive feats of civil engineering, the Romans had extended towns across southern Europe (Figure 12.4.6), connected with a magnificent system of roads. Roman cities, many of them located inland, were based on the grid system. The center of the city, “forum,” surrounded by a defensive wall, was designated for political and commercial activities. By A.D. 100, Rome reached approximately one million inhabitants, while most towns were small (2,000-5,000 inhabitants). Unlike Greek cities, Roman cities were not independent, functioning within a wellorganized system centered on Rome. Moreover, the Romans had developed very sophisticated urban systems, containing paved streets, piped water and sewage systems and adding massive monuments, grand public buildings,, and impressive city walls. In the 5th century, when Rome declined, the urban system, stretching from England to Babylon, was a well-integrated urban system and transportation network, laying the foundation for the Western European urban system.

Although urban life continued to flourish in some parts of the world (Middle East, North and sub-Saharan Africa), Western Europe recorded a decline in urbanization after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century. During this early medieval period, A.D. 476-1000, also known as the Dark Ages, feudalism was a rurally oriented form of economic and social organization. Yet, under Muslim influence in Spain or under Byzantine control, urban life was still flourishing. As Rome was falling into decline, Constantine the Great moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Byzantium, renaming the city Constantinople which is current Istanbul in Turkey. With its strategic location for trade, between Europe and Asia, Constantinople became the world’s largest city, maintaining this status for most of the next 1000 years.

Most European regions, however, did have some small towns, most of which were either ecclesiastical or university centers (Cambridge, England and Chartres, France), defensive strongholds (Rasnov, Romania), gateway towns (Bellinzona, Switzerland), or administrative centers (Cologne, Germany). The most important cities at the end of the first millennium were the seats of the world-empires/ kingdoms: the Islamic caliphates, the Byzantine Empire, the Chinese Empire, and Indian kingdoms.

12.4.2 Site and Situation Factors for City Development

Chances are that many different factors are responsible for the rise of cities, with some cities owing to their existence to multiple factors and cities that arose as a result of more specific conditions.

Source: “Praha Petrin Hladova zed” by Che via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5.

Two underlying causal forces contribute to the rise of cities. Site location factors (see chapter 1) are those elements that favor the growth of a city that is found at that location. Site factors include things like the availability of water, food, good soils, a quality harbor, and characteristics that make a location easy to defend from attack. Situation factors are external elements that favor the growth of a city, such as distance to other cities, or a central location. For example, the exceptional distance invading armies have had to travel to reach Moscow, Russia, has helped the city survive many wars. Most large cities have good site and situation factors.

Source: “Gibraltar World Wind view annotated” by NASA World Wind (image), Prioryman (annotations) via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC0 1.0.

To provide another example, Gibraltar is on a peninsula which is its site and is located at a strategic position in the south of Spain at the intersection of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean which is its situation factor (see Figure 12. )

12.4.3 Defensible Site Locations

Indeed, the earliest incarnation of cities offered residents a measure of protection against violence from outside groups for thousands of years. Living in a rural area, farming or ranching, made any family living in such isolation vulnerable to attack. Small villages could offer limited protection, but larger cities, especially those with moats, high walls, professional soldiers, and advanced weaponry, were safer.

Source: “Heidelberg Castle in 1620 (redrawing from 1902)” by Matthäus Merian via Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain.

The safest places were cities with quality defensible site locations. Many of Europe’s oldest cities were founded on defensible sites. The European feudal system was built upon an arrangement whereby the local lord/duke/king supplied protection to local rural peasants in exchange for food and taxes. For example, Paris and Montreal were founded on defensible island sites. Athens was built upon a defensible hillside, called an acropolis. The Athenian Acropolis is so famous that it is called merely The Acropolis. On the other hand, Moscow, Russia, takes advantage of its remote situation. Both Napoleon and Hitler found out the hard way the challenges associated with attacking Moscow.

In the United States, the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans have primarily functioned as America’s defensive barriers, and therefore few cities are located on defensive sites. Washington, D.C. has no natural defense-related site or situation advantages. On the only occasion the U.S. was invaded, the city was overrun by the British in the War of 1812. The White House and the Capitol were burned to the ground. The poor defensibility of the American capital led to numerous calls for its relocation to a more defensible site during the 1800s. This is partly the reason, so many state-capitol buildings in the Midwest closely resemble the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C.; many states were trying to lure the seat of the Federal government to their state capital.

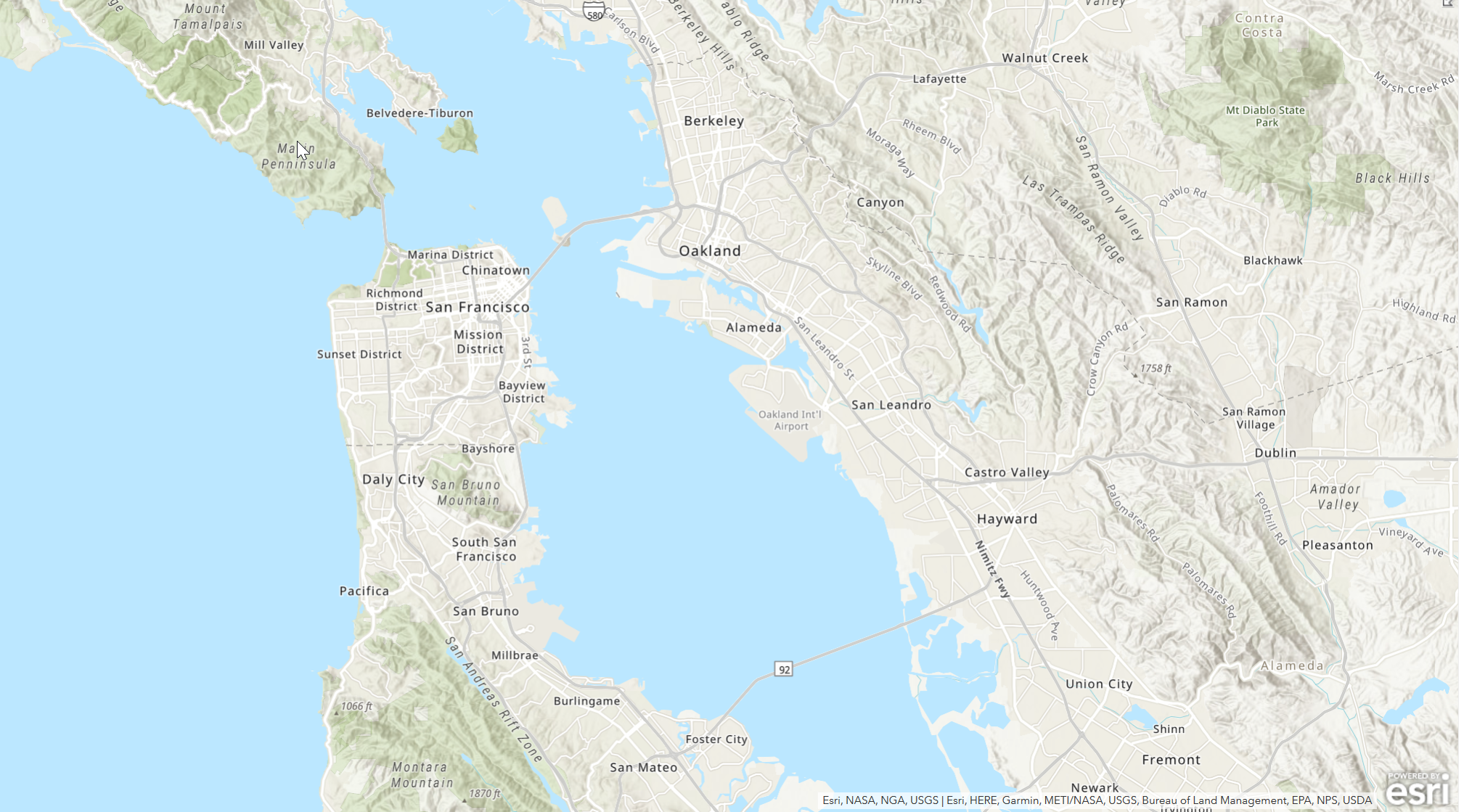

San Francisco is the best example of a large American city founded upon the basis of its defensibility. Located on a peninsula between the Pacific Ocean and a large bay, San Francisco was established where it is because of the military advantage provided by that site. San Francisco boasts two kinds of defensible site advantages. It is both a peninsula site and a sheltered harbor site. Cannons positioned on either side of the Golden Gate could fire upon any enemy ships trying to pass into the San Francisco Bay. Armies coming northward up the peninsula would be forced into a handful of narrow passes where the Spanish Army could focus their defenses. These site advantages led the Spanish to establish the fort, El Presidio Real de San Francisco, there in 1776. The U.S. Army took control of the fort in 1846, and it remained a military base until 1994.

Source: A screenshot of the San Francisco map created using ArcGIS Online by Barbara Crain.

12.4.4 Important Functions as Site Factor

Source: “Paris Île de la Cité Île St Louis Jussieu Jardin des Plantes Panthéon Quartier Latin Louvre Palais Royal Les Halles Hôtel de Ville” by Eric Salard via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

People who possess a specific skill set to become a site factor that can significantly affect the location and growth of a city. One specialized skill set was confined to the priestly class, and proximity to religious leaders is another probable reason for the formation of cities. Priests and shamans would have likely gathered the faithful near to them, so that, as the armies of the lordly class, they could offer protection and guidance in return for food, shelter, and compensation (like tithes). The priestly class was also the primary vessels of knowledge – and the tools of knowledge like writing and science such as astronomy, planting calendars, medicine, so a cadre of assistants in those affairs would have been necessary. Mecca and Jerusalem are probably the best examples of holy cities, but others dot the landscape of the world. Rome existed before the Catholic faith, but it assuredly grew and prospered as a result of becoming the headquarters of Christianity for hundreds of years.

Cities may have evolved as small trading posts where local farmers and wandering nomads exchanged agricultural and craft goods. The surplus wealth generated through trade required protection and fortifications, so cities with walls may have been built to protect marketplaces and vendors.

Throughout history, cities, big and small, have served market functions for those who live in adjacent hinterlands. Some market cities grow much more substantial than others because they are more centrally located. Central location relative to other competing marketplaces is another example of an ideal situation factor. Large cities have excellent site and situation characteristics. Every major US city, including New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Houston is located ideally for commerce and industry.

Some cities grow large because of specific site location advantages that favor trade or industry. All cities compete against one another to attract industry, but only those with quality site factors, like excellent port facilities and varied transportation options, grow large. Cities ideally located between significant markets for exports and imports have unique situation factor advantages versus other competing cities and will grow most.

12.4.4.1 Transportation Advantages and Break of Bulk

Most large cities in the United States emerged where two or more modes of transportation intersect, forming what geographers call a break of bulk point. Breaking bulk happens whenever cargo is unloaded from a ship, truck, barge, or train. Until the 1970s, unloading (and reloading) freight required a vast number of laborers, and therefore any city that had a busy dock or port or station attracted workers. Los Angeles, Chicago, New Orleans, and Houston all grew very large because multiple transportation modes well served each.

New York City is the largest city in the United States, but it was not always that way. It outgrew competitors on the East Coast because of the specific advantages of transportation. Early on, Boston and Philadelphia were more significant, but New York City’s break of bulk advantages helped it immensely. Key among the factors helping New York out-compete rivals were its additional transportation options. First, it had a port on the Atlantic Ocean. Second, it had the navigable Hudson River, which served inland cities far from the ocean via riverboat and barge. Then, in 1825, the Erie Canal opened, effectively connecting the Atlantic Ocean with Lake Erie and all the markets of the Great Lakes Region via New York City. The canal was a massive advantage. With the opening of the canal, agricultural products coming from the Midwest could be transported across the Great Lakes and Erie Canal to New York City, where it was off-loaded from riverboats to ocean-going ships headed for Europe. Simultaneously, goods coming from Europe and destined for any location in the Midwest had to be unloaded at the port in New York City. The additional jobs working at docks and warehouses attracted other industries, and a snowball effect was achieved by the mid- 1850s that made New York City, for a time, the largest city in the world.

With all of this in mind, it is possible to develop a view of cities that is based on innovations and diffusions of technology. This is what was done by the geography of John R. Borchert[1] during the 1960s. Borchert developed a view of the urbanization of the United States that is based on the epochs of changing technology, i.e. the changing means of transportation. As the components of technology wax and wane, the urban landscape undergoes dramatic changes.

- Stage 1: Sail-Wagon Epoch (1790–1830); the only means of international trade was sailing ships. Once goods were on land, they were hauled by wagon to their final destination.

- Stage 2: Iron Horse Epoch (1830–70); characterized by the impact of steam engine technology, and development of steamboats and regional railroad networks.

- Stage 3: Steel Rail Epoch (1870–1920); dominated by the development of long-haul railroads and a national railroad network.

- Stage 4: Auto-Air-Amenity Epoch (1920–70); with growth in the gasoline combustion engine.

- Stage 5: Satellite-Electronic-Jet Propulsion (1970–?), also called the High-Technology Epoch. This stage has continued to the present day as both transportation and technology improves.

12.4.4.2 Head of Navigation

Source: “Piedmont province within Appalachians Highlands division physiographic division” by Deanrah via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Rivers have also played an essential role in the establishment of cities. Most cities are established along rivers of some sort. Rivers provide fresh water for drinking (and irrigation), but the effect navigable rivers have had on urban growth is hard to overstate. Before the age of trains and highways, rivers were by far the most efficient way to transport heavy cargo, especially over long distances. Interestingly, the interruptions to river navigation were most often responsible for creating conditions that attracted settlement and favored growth. Waterfalls were for many years a complete nuisance to river traffic, but they also are responsible for several cities. Not only do waterfalls provide a source of power for industry (see fall line cities below), but they also create a special kind of break of a bulk point called a head of navigation. At a waterfall, people had to stop, get out of their boats and carry the boat, and their cargo.

Richmond, VA, exemplifies a head-of-navigation site, having developed adjacent to the falls of the James River. Here, the James River cascades over a waterfall, necessitating that boats stop and unload their cargo. This activity created jobs at the docks and in warehouses, while also stimulating manufacturing. Richmond is just one of many cities that emerged along the Piedmont fall line, as illustrated on the map above.

12.4.4.3 Portage Sites

The process of carrying boats and/cargo between two navigable stretches of the river (or to another river) is called Portage. Towns evolve where important portages zones arose. Indiana, New York, Ohio, Wisconsin, Michigan and Maine all have municipalities named “Portage,” but the most important portage zone in the United States appeared in Chicago, Illinois. Just southwest of what is now downtown Chicago, near Midway Airport was a portage zone where the Chicago River, which flows north into the Lake Michigan nearly intersected the Des Plaines River, which flows southward into the Mississippi River system. Around 1850, the people of Chicago built a canal connecting America’s two greatest navigable water systems, and by doing so gave Chicago an enormous transportation advantage over other locations in the Midwest.

12.4.4.4 Ford Sites

Rivers also create chokepoints for the movement of goods and people traveling by land. Rivers are often difficult to cross in many locations because the water either the water is too deep or the river too wide. In such places, before bridges were common, those trying to cross a river would seek out a ford, which is a shallow place to cross the river without a boat. City names like Stratford, Oxford, and Frankfurt all contain clues that they were once good places to cross a river. These fording sites often were simultaneously ideal locations for bridge construction because engineering a bridge across a shallow part of a wide river is simpler at a ford. Bridges funnel overland traffic to specific points, and provide another break of bulk opportunity, especially if the river is navigable.

12.4.4.5 Water Advantage

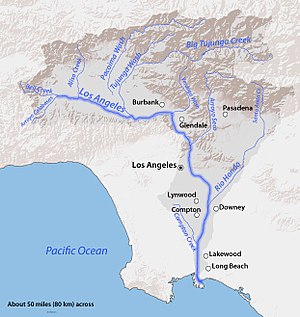

Source: “Los Angeles River from Fletcher Drive Bridge 2019” by Downtowngal via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Los Angeles (L.A.) is the great metropolis on the west coast of the United States. The Spanish chose a location near what is now downtown L.A. for a pueblo (town) because they found fertile soil and a consistent source of water there alongside a large population of Indians that they hoped would form the core of a vibrant Spanish colony. As years went by, Los Angeles’ only significant advantage over potential competitors in Southern California was its river. Spanish water law declared all the water in the L.A. River belonged to the people of Los Angeles. This law prevented other towns from forming either upstream or downstream from the original pueblo. People living along the L.A. River and hoping to use its precious waters were forced by Los Angelenos to become part of L.A. Los Angeles remained a small town until the Santa Fe/Southern Pacific Railroad opened a second transcontinental railroad terminus in L.A. in 1881.

Source: “LARmap” by USGS, everything else by Shannon1 via Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain.

Not long afterward, the local port facilities at San Pedro were upgraded, and L.A. began competing with San Francisco for business. With the invention of refrigerated boxcars and the discovery of oil in the region, L.A. grew quickly. Good weather helped encourage migrants to journey westward to take jobs in the petroleum and citrus industries. The same great weather helped attract the movie and aeronautical industries decades later. Water resources though have remained a problem. The Los Angeles River was never sufficient to serve the needs of a large city, so a series of canals and pipelines have been constructed over the years to bring fresh water from vast distances into the Los Angeles region.

- Palm, Risa, "John Borchert’s “American Metropolitan Evolution”" (2010). Geosciences F aculty Publications. 16. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/geosciences_facpub/16 ↵