Chapter 12: Urban and Suburban Spaces

12.8 Major Elements of the US City

North America’s urban landscape has been shaped both by colonization and by industrialization. Most of the early settlements in the region were small and were located close to the eastern coast. The Appalachian Mountains provided a formidable obstacle for early settlers before 1765. As settlement and colonization expanded, people moved steadily westward, still primarily situating close to waterways. Even today, most urban centers are located close to water.

During this time, immigration and natural growth expanded North America’s population. In 1610, the population of what is now the United States, excluding indigenous groups, was a meager 350 people. In just 200 years, the population reached over 7 million. In 1620, just 60 people occupied what is now the Canadian city of Quebec. Today, the population of the United States stands at over 318 million and Canada’s population is over 35 million and both countries are highly urbanized.

12.8.1 The Central Business District

Source: Photo by Barbara Crain, CC BY 4.0

Central Business Districts (CBDs) in the United States began to take shape in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the rise of industrialization and urbanization. Initially, CBDs emerged as the focal points of cities’ commercial activities, characterized by dense concentrations of office buildings, banks, department stores, and other commercial enterprises. These areas were typically located near major transportation hubs, such as railway stations and ports, facilitating trade and commerce. These areas were often surrounded by worker’s homes.

12.8.2 The City Neighborhood

Where you live or grew up, is an element of your identity. “Where’s your hometown?” is a common question you might hear if you went on vacation or moved away. If you’re from a large city, what side of town, or what neighborhood you come from is another source of identity formation. Exactly what defines a “neighborhood” is open to debate. The US Census Bureau does not define “neighborhood” because they are vernacular regions. Each person has a sense of where neighborhood boundaries are, but those boundaries are largely in the imagination of individuals. Census tracts nd ZIP codes sometimes function as proxies for neighborhoods, but they are oftennarbitrary as well. In some parts of the city, citizens have very specific ideas about neighborhood boundaries. Gangs often use graffiti to mark specific locations to notify others about their opinion on neighborhood boundaries or territories.. In some cities, like Los Angeles, the designation of unofficial neighborhoodboundaries has been the source of angry debates because property values are greatly affected by the simple perceptions of where neighborhood boundaries exist.

Obviously, most neighborhoods don’t have organized gangs, but still, people with long-term commitments to homes and neighbors do engage in numerous group behaviors to protect their “turf”, and indirectly, the value of their property. Most of the time, these behaviors are benign – things like keeping weeds out of the yard, ensuring that local authorities enforce zoning laws about signs, junk cars, or residency restrictions. Neighbors may use the Nextdoor Neighbor app to get to know like-minded neighbors and form friendships. Neighbors may work together to improve local schools, parks, and hospitals. Homeowners may band together to accomplish other goals that might be deemed unsavory. They might want to keep certain businesses, like liquor stores, payday lenders, factories or nightclubs from their neighborhoods. They may even work together to prevent specific individuals, like sex crime offenders or the homeless, from moving in the neighborhood. Because many of these same individuals are less concerned when factories, stores or homeless people come to other neighborhoods, the term “not in my backyard” or “NIMBY” was coined to characterize the militant protectionist attitude. Generally, neighborhoods with wealthier people who are politically active, and have long-term residency patterns exhibit NIMBYism. Wealthier neighborhoods may erect gates and hire guards to prevent easy access to homes.

When residents in a neighborhood lack money, political organizational skills, or the motivation to protect themselves from disamenities, significant neighborhood degradation is possible. When that degradation affects the health of a local population of an ethnic minority, the term environmental racism is sometimes applied to describe the situation. What is racist is often hard to discern because cause and effect are not always obvious. Was a neighborhood polluted before minorities moved there, or did polluters move in after the minorities moved in? Did minorities populate a polluted neighborhood because that was all they could afford or were they forced to live there by law or precedent or proximity to their employment? Poverty is frequently at the root of these issues. Poor people of all ethnicities rarely can afford to live in neighborhoods that have outstanding schools, parks, air quality, etc., and so they are often able to afford to live only in the most dangerous, toxic, degraded neighborhoods.

Environmental Racism and Justice

Environmental justice concerns in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans revealed deep-seated inequalities that exacerbated the impact of the storm on marginalized communities. The Lower Ninth Ward, a predominantly African American neighborhood with high poverty rates, bore the brunt of Katrina’s devastation. Inadequate flood protection infrastructure and levee failures led to catastrophic flooding, displacing thousands of residents who struggled to evacuate due to limited resources and mobility options. The government’s response was widely criticized for its slow and ineffective aid distribution, further compounding the hardships faced by residents.

The environmental justice perspective highlighted how these vulnerable communities, historically neglected in terms of infrastructure investment and disaster planning, suffered disproportionately compared to wealthier and predominantly white neighborhoods. Residents in affluent areas had better access to resources such as private transportation, insurance coverage, and quicker evacuation options, buffering them from the worst impacts of the storm. In contrast, neighborhoods like the Lower Ninth Ward faced longer recovery times, housing insecurity, and health risks from exposure to contaminated floodwaters and mold.

Katrina underscored systemic failures in addressing environmental hazards and social vulnerabilities, prompting calls for policy reforms and community empowerment in disaster preparedness and response. Grassroots organizations and advocacy groups mobilized to demand equitable recovery efforts, infrastructure improvements, and investment in affordable housing and healthcare services for affected communities. The event sparked a broader national dialogue on environmental racism and justice, emphasizing the need for inclusive and fair approaches to resilience and disaster management to prevent similar injustices in the future.

The neighborhood life cycle: How people come to occupy specific neighborhoods is a complex process that evolves over time and involves thousands of individual and institutional decisions. Some of these processes such as blockbusting (see Ethnicity chapter) are rooted in systemic ethnic discrimination. However, economic decisions also factor prominently in the lifecycle of a neighborhood. As housing ages, it tends to become less desirable. People with enough money tend to move away wanting more space and buy newer homes elsewhere. The lower classes move into the older homes, frequently as renters. Often poor people wind up occupying older, multi-family dwellings or apartments. Roofs and pipes leak, heating and cooling systems are often inefficient, neighborhoods are congested, etc. Sometimes, entire neighborhoods are abandoned. This process is known as the neighborhood life cycle.

In cities where housing is scarce, the neighborhood cycles of decline is sometimes reversed when wealthier individuals choose to move in, renovate, and sometimes completely rebuild entire blocks or an entire neighborhood. These renovation efforts are referred to as gentrification (discussed in Chapter 12.9)

12.8.3 Suburbs

Between the urban core and the rural hinterland, serving as a kind of buffer and transition zone between the two, are suburbs or suburban spaces. Suburbs first appeared in the United States in the mid-1800s as trolleys and other types of light rail extended beyond the limits of the pre-industrial, pedestrian-oriented cities. Light rail allowed middle-class families to move out beyond the city limits into communities called streetcar suburbs. When automobiles became affordable in the 1920s, suburbanization expanded. The Great Depression and World War II slowed suburbanization in the US, but during the 1950s, suburbs exploded on the American Landscape. The rise of suburbs in the post-WWII era brought profound changes to American cities. Many families found themselves able to exchange an old house in the crowded city for a new one with a bigger yard, near new schools, malls, parks, and hospitals. It was the culmination of the American dream for loads of people. The US and many local governments were eager to help people achieve those dreams, and created numerous financial incentives to make suburban dreams inexpensive, but government policies also created multiple unintended consequences (see Chapter 12.9 on Redlining). The suburbs are primarily residential but also have public services like schools and businesses people need to rely on to go about their daily lives. Plenty of people live and work in the suburbs, but commuting to work in or near the urban center and living in the suburbs is the predominant pattern. With the decrease in housing density and the increase in both home size and acreage, however, came sprawl.

Suburban Problems

Overcrowding in the suburbs has become a problem. Older suburbs, though rarely approaching the mega density of the inner-city core, often come to match (or exceed) the density in the rest of the city proper. One such example is “America’s Suburb”, the San Fernando Valley, that occupies much of the northern half of Los Angeles. It was sparsely settled prior to World War II, yet today, it has several neighborhoods with population densities in excess of 50,000 per square mile. The Los Angeles area highway network, once a model of efficiency, was quickly overburdened by unchecked suburbanization. US Highway 101 which stretches across the southern San Fernando Valley exceeded capacity in 1974, but suburbanization along US 101 continues today with commuters regularly driving on US 101 for 40 miles before even getting to the western edge of the San Fernando Valley. The intersection of US 101 and Interstate 405, in the southeastern corner of the San Fernando Valley consistently ranks as the most congested in the US, at over 350,000 cars per day.

Source: “Bellefonte Pennsylvania” by Dhaluza via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Suburbanization and urban sprawl refers to the expansion of suburbs without a population to match; in other words, infrastructure may have been built, electrical lines may have put up, but the space is not yet occupied with people. If you have ever driven through a neighborhood with brand new houses, usually looking pretty similar to each other (having standardized housing allows for quick construction and can be less expensive to purchase) but only a handful seem to be occupied, you’ve likely witnessed sprawl. An obvious critique of sprawling suburbs is the extreme consumption of land through this development pattern.

Urban sprawl’s broader definition includes in addition to the extension of low-density residential also extension of commercial, and industrial development into areas beyond a city’s boundaries that occur unplanned or uncoordinatedly (Figure 12. ). It is generally characterized by the following:

- low-density development that is dispersed and situated on large lots (greater than one acre)

- geographic separation of essential places such as work, home, school, and shopping

- high dependence on automobiles for travel

- increased impervious surface area in watersheds

- habitat fragmentation and degradation

Click on the link for a good story map on urban sprawl.

Source: “Map of Golden Triangle from OpenStreetMap” by Open Street Map contributors via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Cities and suburbs in the United States exhibit distinct characteristics shaped by their unique layouts and lifestyles. Urban areas typically follow a grid system, with straight streets intersecting at right angles, facilitating efficient navigation and accessibility. This design supports a dense population, allowing for diverse amenities, robust public transportation networks, and a vibrant, walkable environment. The concentration of businesses, cultural institutions, and entertainment options in cities creates a dynamic atmosphere where people can live, work, and socialize in close proximity. However, this density can also lead to congestion, higher living costs, and limited green spaces.

Urban sprawl combines low density and fragmentation of the urban area increases the average travel distances for daily trips. The 1950s and 1960s in the United States are classically considered major periods of suburban development. This was in part due to changes in transportation which made it possible to more easily commute in and out of the city center, the culture of consumerism, and also because it was during the post-war era when families were reunited and expanding, and the government had programs incentivizing the construction and selling of houses for veterans. The creation of the Interstate system in particular changed the paradigm of commuting over long distances. Interstates not only connected major cities to each other, but cut through many cities themselves. As a result, suburbanites could live dozens of miles from the center of the city, but still commute via personal automobile in a reasonable time frame.

One such effort can be seen in Levittown, a planned community in Pennsylvania which had cookie-cutter houses specifically built for veterans. The video below shows historical footage of a house going up in a day in Levittown.

12.8.4 Exurbs

An additional patterns of suburban development are exurbs. Exurbs are residential, prosperous, but rural areas beyond the suburbs. In the United States, the Census Bureau defines areas as either urban or rural mostly on the basis of population density. There is no definition for suburbs or exurbs at the federal government level. Generally, most suburbs maintain a high enough population density (roughly 1000 people per square mile or more) that the Census Bureau categorizes them as ‘urban’. But, there are large swaths of land within commuting distance of cities that are defined as rural; in fact, the majority of land inside metropolitan areas is actually rural. This does not mean agricultural, however; there are many that live lifestyles quite connected to the nearby urban core but live in low population regions in the metropolitan area. These areas are the exurbs and the people are exurbanites. A major way of distinguishing between exurban areas and what we colloquially think of as rural is to understand the development pattern and the people occupying the space. Exurbs are generally affluent, shown by statistics on income levels or observing the large footprints of houses. Exurbanites are largely still connected to urban living via commuting and culture.

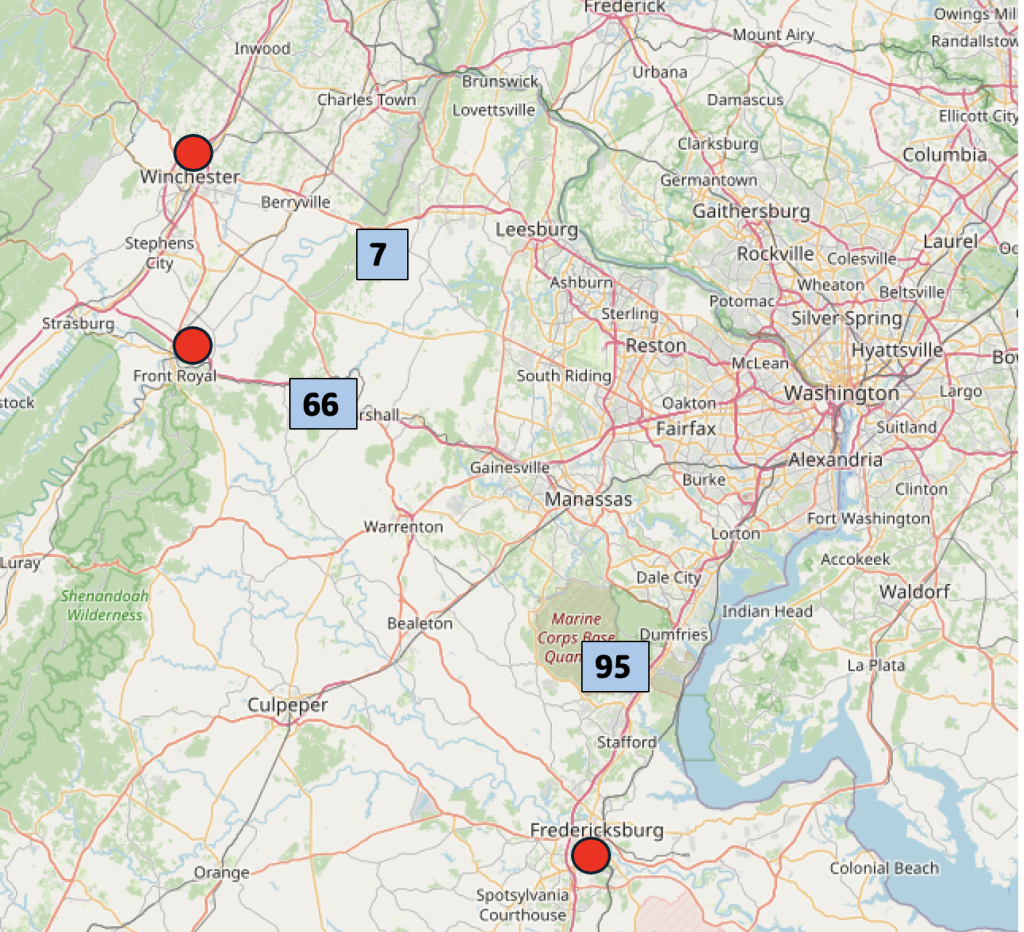

Front Royal and Winchester, both located in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, can be considered exurbs to some extent, though there are differences in their development patterns and proximity to major urban centers. Front Royal (driving distance measured to the DC mall is 1 hr 15 min, 68 miles), situated at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, is removed from major urban areas like Washington, D.C., and Northern Virginia yet is well connected via Route 66. While it has experienced some suburbanization and population growth over the years, it retains a more rural character with larger lots, open spaces, and a slower pace of life compared to closer-in suburbs.

Winchester, located a little further north in Virginia (driving distance to DC mall: 1 hr 31 min/ 75 miles), is even further away from the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area but has seen more substantial suburban development. It is possible that the university and the accompanying urban life attracts young Virginians and commuters. Compared to Front Royal it serves as a regional hub with a larger population, more extensive commercial and retail amenities, and a greater degree of urbanization .

Fredericksburg, situated in Spotsylvania County (driving distance to DC mall: 1 hr 30 min/ 51 miles) is closer to the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area and has seen more significant suburban development. It offers a mix of suburban amenities such as shopping centers, residential neighborhoods, and commuter options, making it a popular choice for those seeking a balance between urban access and suburban living. Fredericksburg is often included within what is called the ‘Greater Washington Area’.

12.8.5 Edge Cities

Another urban phenomenon is that of edge cities. Edge cities are new concentrations of business, retail, and residences outside of the urban core. They are so named edge cities as they are located on the edge of the traditionally denser development of a major city, but edge cities themselves are starting to be centers in their own right. The classic example of an edge city is Tyson’s Corner in Northern Virginia or Short Pump around Richmond, VA. Tyson’s Corner started at a crossroads of Rt. 7 and Rt. 123 along with a few buildings such as a country store and surrounded by mostly farmland. Once the Capital Beltway was built smack in that area in the early 1960’s, development occurred in the form of a new mall in 1969. From then on, development occurred quickly and it really took off once it was known that the metro would connect Tysons (as it is now known) to DC and now to Dulles Airport as well.

Edge cities are distinguishable from the surrounding suburbia by possessing development density (as viewed through taller buildings) and the presence of service/retail and office employment. However, edge cities do not have the density of ‘traditional’ urban cores. Other ways in which edge cities are unique compared to traditional cities are that edge cities:

- Are often unincorporated, meaning they lack municipal borders and local government;

- Tend to have spread out, car-centric development;

- Are often sited at the junctions between highways and expressways.

Emphasizing the first point above, most edge cities are not legally-defined cities!

Edge cities developed in three waves. First, there was suburbanization of the population. People moved from the urban core into suburban developments. Then, retail suburbanized in new developments in malls. This ‘malling of America’ brought retail from the urban core to locations closer to the stores’ affluent customer base. Third, companies and industry moved to these areas as the rent is cheaper and the labor force is easily available.. White collar employers found cheaper land to build headquarters or to otherwise expand their business footprint within the region. As the third point above details, malls and employers tended to concentrate near junctions of large roads, facilitating the personal automobile as the primary means of transportation into these new centers.