Chapter 11: Economy and Development

11.6 Changing Roles of Women in Development

In the world of work there continue to be pronounced imbalances across genders, reflecting local values, social traditions, and historical gender roles. Unpaid care work includes housework, such as preparing meals for the family, cleaning the house and gathering water and fuel, as well as work caring for children, older people and family members who are sick—over both the short and long term. Across most countries in all regions, women work more than men. Women are estimated to contribute 52 percent of global work, men 48 percent.

Source: Screenshot taken from the Sustainable Development Goals – Executive Summary (Oct. 12, 2017).

Of the 59 percent of work that is paid, mostly outside the home, men’s share is nearly twice that of women—38 percent versus 21 percent. The picture is reversed for unpaid work, mostly within the home and encompassing a range of care responsibilities: of the 41 percent of work that is unpaid, women perform three times more than men—31 percent versus 10 percent. Hence the imbalance—men dominate the world of paid work, women that of unpaid work. Unpaid work in the home is indispensable to the functioning of society and human well-being: yet when it falls primarily to women, it limits their choices and opportunities for other activities that could be more fulfilling to them.

Occupational segregation has been pervasive over time and across levels of economic prosperity—in both advanced and developing countries men are overrepresented in crafts, trades, plant and machine operations, and managerial and legislative occupations; and women in mid-skill occupations such as clerks, service workers, and shop and sales workers.

Even when doing similar work, women can earn less—with the wage gaps generally greatest for the highest paid professionals. Globally, women earn 24 percent less than men. In Latin America, top female managers earn on average only 53 percent of top male managers’ salaries. Across most regions women are also more likely to be in “vulnerable employment”—working for themselves or others in informal contexts where earnings are fragile, and protections and social security are minimal or absent.

As a method to measure development progress around the world, the United Nations has created first the Millennium Development Goals which soon changed to the SDGs discussed in chapter 11.6. The goal addresses Gender equity and empowered women – the United Nations uses a Gender Inequality Index (GII). The index uses a variety of methods to determine the inequality of females compared to males including labor, reproductive health, and empowerment. The higher the number that a region receives demonstrates the greater the inequality in that region. Some nations have severe gender inequalities, meaning that women have nearly no legal, social, or economic rights even when they are head of their household. Many argue that if the world focused on gender equality of females, most of our social, economic, and environmental problems would be greatly minimized.

Many societies are experiencing a generational shift, particularly in the educated middle-class households, towards greater sharing of care work between men and women. Legislation and targeted policies can increase women’s access to paid work. Access to quality higher education in all fields and proactive recruitment efforts can reduce barriers, particularly in fields where women are either underrepresented or where wage gaps persist.

Source: Screenshot of the UNICEF Gender Equality website.

UNICEF works to improve conditions for women worldwide. Click on the photo and explore the web site.

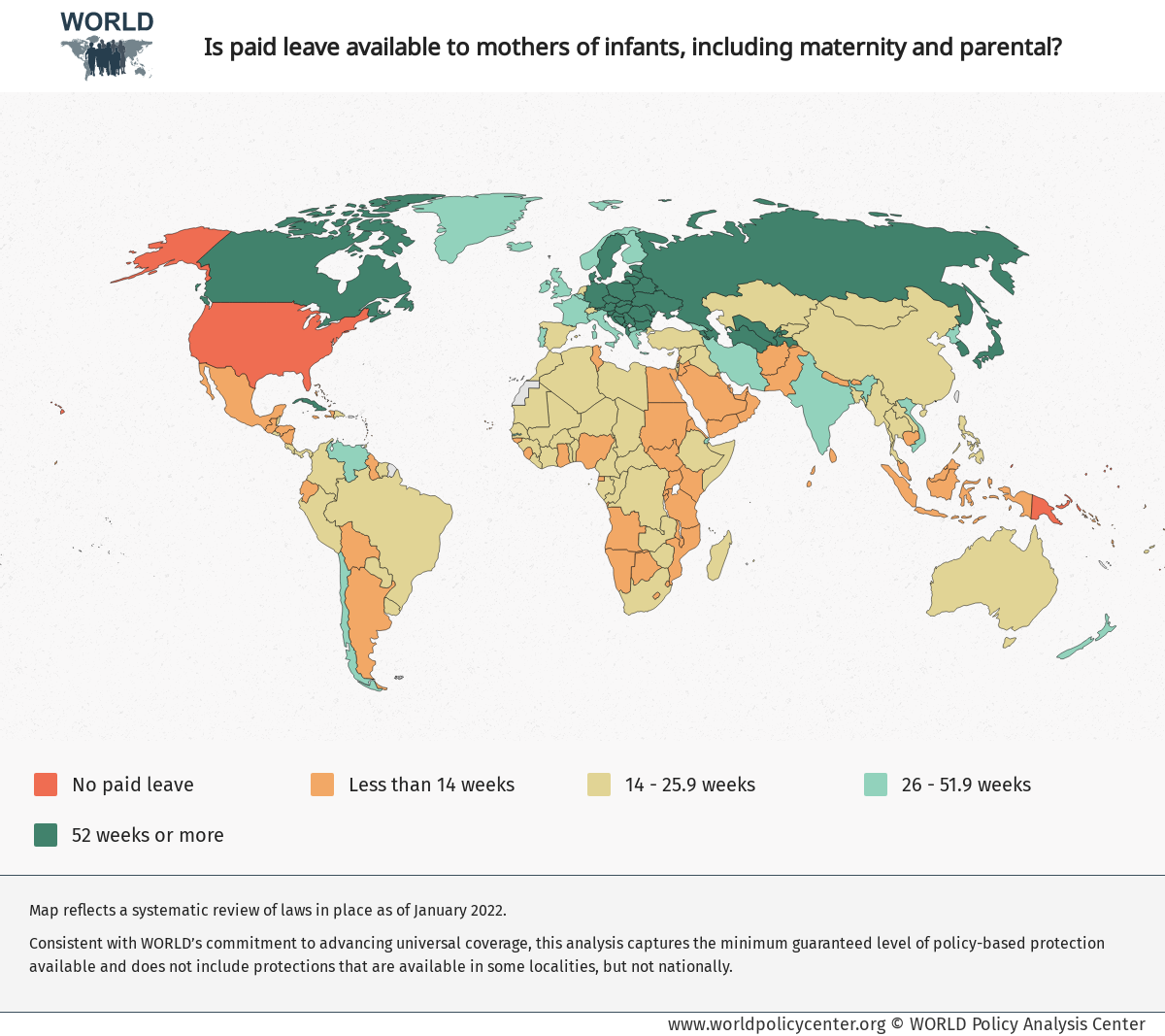

Policies can also remove barriers to women’s advancement in the workplace. Measures such as those related to workplace harassment and equal pay, mandatory parental leave, equitable opportunities to expand knowledge and expertise and measures to eliminate the attrition of human capital and expertise can help improve women’s outcomes at work. Paid parental leave is crucial. More equal and encouraged parental leave can help ensure high rates of female labor force participation, wage gap reductions and better work–life balance for women and men. Many countries now offer parental leave to be split between mothers and fathers.

Figure 11.6.3 above shows paid material leave across the world. Get into the map and check for the length difference – it seems Czechia has the longest duration, possibly. Notice that the US is among those countries between 60-90 days of paid leave which is up to the employer.

Source: “Is paid leave available to mothers of infants, including maternity and parental?” by World Policy Analysis Center.

The map on Figure 11.6.4 is developed and updated by the World Policy Center and shows that most countries in the world have mandatory maternity leave. If you go the site of the World Policy Center by clicking on the map you can discover that in most of the cases there is job protection also.