Chapter 10: Agricultural and Food Systems

10.8 Food Security and Insecurity

Source: United Nations – The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023

10.8.1 Food Security and Food Insecurity

the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal #2 – Zero Hunger looks to “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture”.

The amount and type of food we consume varies across space as does our safe and secure access to food. This chapter opened by defining food security as having steady, affordable, and safe access to sufficient and nutritious food and food insecurity as just the opposite.

DEEPEN YOUR UNDERSTANDING: Read more about food insecurity as explained by Feeding America here and be sure to view the chart that appears on the linked page.

The National Research Council identifies four major issues that affect food security worldwide:

- Regions and countries that produce agricultural goods do not overlap with where goods are consumed.

- More and more agricultural land converts to urban use (often: urban sprawl in the US).

- More food crops are used for biofuel production / and or other non-food consumption purposes. For example, in the United States in 2020, 35% of corn was grown for animal feed, 31% for biofuel and less than 2% for direct human consumption.

- Producers weigh fluctuating price factors as it obviously impacts their profit. Factors could be: whether they are using hydrocarbons (fossil fuels) to run implements and irrigation systems; buying farm insurance; taking out loans for operations, equipment, or land; taking out a bridge loan to stay afloat; selecting an expensive drought-resistant seed or a less-expensive seed; selecting and applying fertilizers and pesticides; or buying or renting land.

10.8.2 Food Insecure Regions

We can produce enough food in the world as a whole, but there will still be problems of food security at the household or national level. In urban areas, food insecurity usually reflects low incomes, but in poor rural areas, it is often inseparable from problems affecting food production. In many areas of the developing world, the majority of people still depend on local agriculture for food and livelihoods, but the potential of local resources to support further increases in production is very limited, as technology to produce larger crops is limited. Examples are semi-arid areas and areas with problem soils. In such areas, agriculture is often dependent on global policies and the ability to offer economic and technological aid.

FAO estimates that around one billion people are undernourished and that each year more than three million children die from undernutrition before their fifth birthday. In addition, physiological needs of pregnant and lactating women also make them more susceptible to malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. Twice as many women suffer from malnutrition as men, and girls are twice as likely to die from malnutrition than boys. Maternal health is crucial for child survival – an undernourished mother is more likely to deliver an infant with low birth weight, significantly increasing its risk of dying.

Source: “NP Himachal Pradesh 68” by CIAT via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

In low income countries, rural women and men play different roles in guaranteeing food security for their households and communities. While men grow mainly field crops, women are usually responsible for growing and preparing most of the food consumed in the home and raising small livestock, which provides protein. Rural women also carry out most home food processing, which ensures a diverse diet, minimizes losses and provides marketable products. Women are more likely to spend their incomes on food and children’s needs – research has shown that a child’s chances of survival increase by 20% when the mother controls the household budget. Women, therefore, play a decisive role in food security, dietary diversity and children’s health.

But gender inequalities in control of livelihood assets limit women’s food production. In Ghana, studies found that insecure access to land led women farmers to practice shorter fallow periods than men, which reduced their yields, income and the availability of food for the household. In sub-Saharan Africa, diseases such as HIV/AIDS force women to assume greater caretaking roles, leaving them less time to grow and prepare food. Women’s access to education is also a determining factor in levels of nutrition and child health. Studies from Africa show that children of mothers who have spent five years in primary education are 40% more likely to live beyond the age of five.

Having an adequate supply of food does not automatically translate into adequate levels of nutrition. In many societies, women and girls eat the food remaining after the male family members have eaten. Women, girls, the sick and disabled are the main victims of this “food discrimination,” which results in chronic undernutrition and ill health.

A phenomenon found in many regions and countries today is the trend towards the socalled “feminization of agriculture,” or the growing dominance of women in agricultural production and the concurrent decrease of men in the sector. This trend makes it more imperative than ever to take action to enhance women’s ability to carry out their tasks in agricultural production and their other contributions to food security. This development goes hand in hand with the increasing number of femaleheaded households around the world.

A major cause of both these developments is male-out migration from rural areas to towns and cities in their countries or abroad and the abandonment of farming by men for more lucrative occupations. In Africa, where women have traditionally performed the majority of work in food production, agriculture is becoming increasingly a predominantly female sector. Economic policies favoring the development of industry, and the neglect of the agricultural sector, particularly domestic food production, have led to an exodus of rural people to the urban or mining areas, to seek income-earning opportunities in mines; large export-oriented commercial farms, fishing enterprises and other businesses.

While there is still insufficient data to give exact figures on women’s contributions to agricultural production everywhere in the world, collection of data is increasing. This data, together with field studies and gender analyses, make it possible to draw a number of conclusions about the extent and nature of women’s multiple roles in agricultural production and food security. If anything, women’s contributions to farming, forestry, and fishing may be underestimated, as many surveys and censuses count only paid labor. Women are increasingly active in both the cash and subsistence agricultural sectors and much of their work in producing food for the household and community consumption, as important as it is for food security, is not counted in statistics.

This chapter has provided language to describe the differences in agricultural practices and unevenness regarding agricultural lifestyles and individual consumptive behavior. To end, watch the videos below, each of which profiles fish cultivation and answer the following questions pertaining to each video:

- What are the processes for securing fish?

- Who is the typical consumer of the fish?

- What types of economic activity (primary, secondary, etc) are present for each process?

- How would you describe each of these fishing landscapes in terms of culture and economy?

- How are the processes in each video related to globalization?

- How could the different ways of fishing relate to food security and insecurity?

10.8.3 Food Waste and Food Loss

Food loss and waste is food that is not eaten.

- Food “loss” occurs before the food reaches the consumer as a result of issues in the production, storage, processing, and distribution phases.

- Food “waste” refers to food that is fit for consumption but consciously discarded at the retail or consumption phases.

The causes of food waste or loss are numerous and occur throughout the food system, during production, processing, distribution, retail and food service sales, and consumption. In the United States, over one-third of all available food goes uneaten through loss or waste. When food is tossed aside, so too are opportunities for improved food security, economic growth, and environmental prosperity.

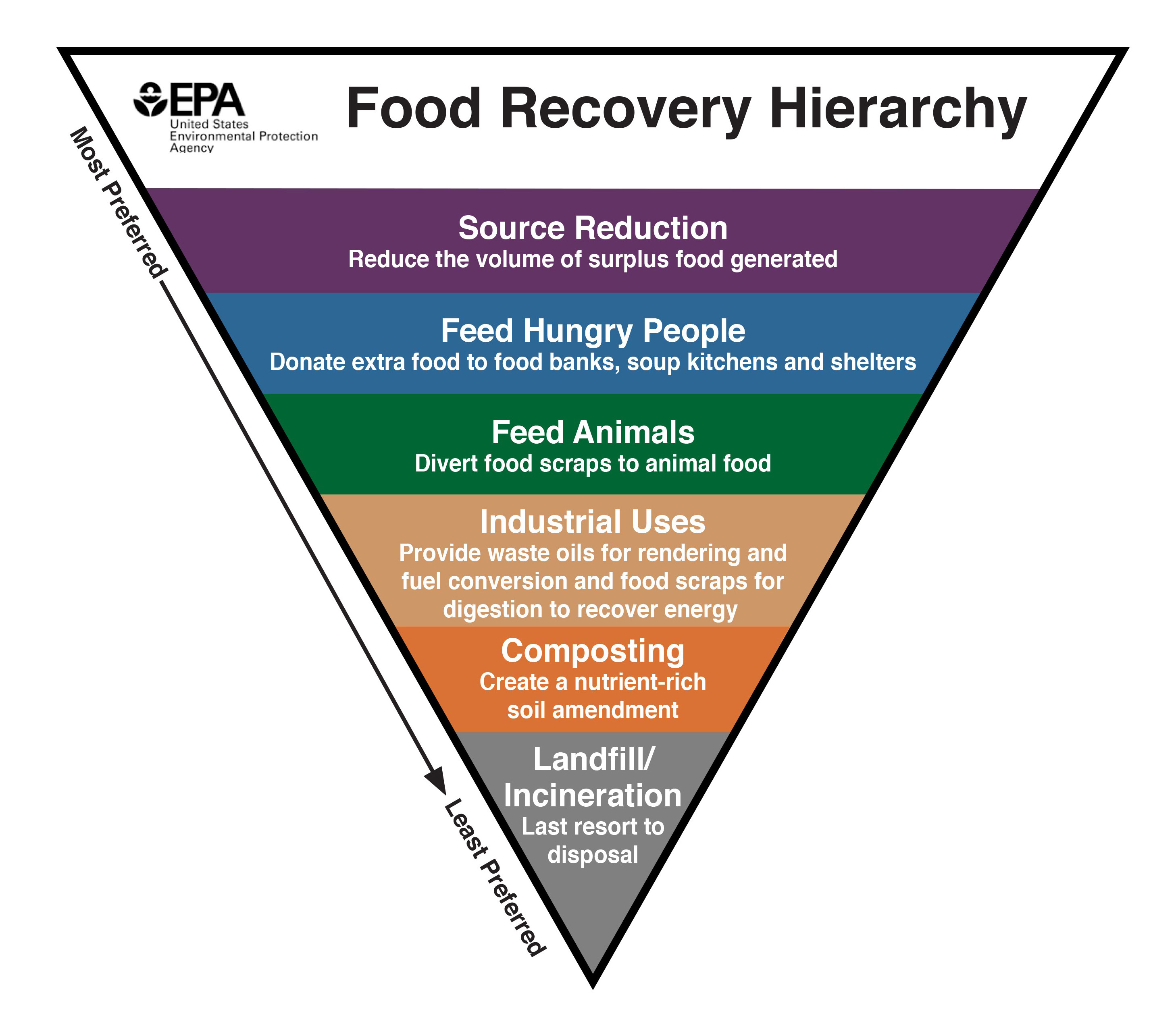

The Food Recovery Hierarchy (graph 10.6 below) prioritizes actions individuals/households and organizations can take to prevent and divert wasted food. Each tier of the Food Recovery Hierarchy focuses on different management strategies for your wasted food.

Source: “Food Recovery Hierarchy” by United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

The United Nations set an International Day of Awareness (Sept 29) on Food Loss and Waste Reduction (this is Goal 12 of the Sustainable Development Goals set by the UN). According to the UN, globally, around 13 percent of food produced is lost between harvest and retail, while an estimated 17 percent of total global food production is wasted in households, in the food service and in retail all together. On their website, the UN provides tips to reduce food waste for individual households.

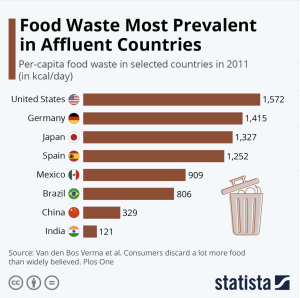

Researchers found that more affluent countries tend to throw out the most food, with Norway, Hong Kong and Germany all on the top of the list and lower income countries wasting much smaller amounts. Out of the 177 countries that were part of the analysis, 40 were identified as not wasting any food per the study setup, since their food availability was below the daily caloric need of their inhabitants.

Source: “Food Waste Most Prevalent in Affluent Countries” by Van den Bos Verma et al. Consumers discard a lot more food than widely believed. Plos One, CC BY SA.

Changing consumer behaviour is particularly challenging. According to Second Harvest, Jan 9, 24 “To make an impact at a household level, France runs national food awareness and education campaigns. It is also enhancing expiration date labels to better guide consumers. The country employs two food labels: DLC (Date Limite de Consommation) for a majority of perishable products and DDM (Date de Durabilité Minimale) for dry, sterilized, and dehydrated products. To convey that these products remain safe beyond the DDM, producers can include wording like “For optimal tasting” or “This product can be consumed after this date” for precision.”

Also in France, for instance, restaurants are encouraged to offer bags for patrons to take home uneaten portions. As of January 1, 2020, supermarkets are required to implement a donation quality management plan to ensure food quality, involving staff training and awareness. Non-compliance may result in fines up to Euro 75,000!

In Korea, it’s illegal to throw food waste in landfills. The country converts a whopping 95% of its food waste into fertilizer, biogas and animal feed. What’s behind this remarkable success? Check out this Lessons from Korea’s Food Waste Policies article –a tax on food waste is part of it!

10.8.4 Food Deserts – Uneven Distribution of Food

Food deserts can be described as geographic areas where residents’ access to affordable, healthy food options (especially fresh fruits and vegetables) is restricted or nonexistent due to the absence of grocery stores within convenient traveling distance.

Often food deserts are identified by the following parameters:

- Urban food desert: distance to nearest grocery store is 1+ miles in area with primarily low-income residents (profiled in the embedded video below)

- Rural Food desert: distance to nearest grocery store is 10+ miles in area with primarily low-income residents

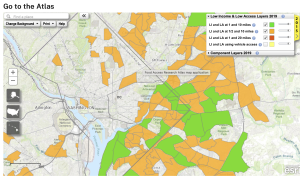

Source: USDA Food Access Research Atlas

Distance from the home location to the food market affects those people that do not own a car, have difficulty walking, and do not have convenient access to public transportation. The factor of distance will most likely be most prominent in rural and suburban areas as urban areas tend to have public transportation. However, supermarkets in cities are often few and far between as economic forces have driven grocery stores out of many cities in recent years. The inner city areas tend to house low-income residents who are often cash-poor and time-poor plus they may not own cars as well. For many residents, convenience stores and fast food chains are the only option. In Figure 10.7 the color green shows Low Income and Low Access at 1 and 10 miles; the color orange depicts Low Income and Low Access at 1/2 and 10 miles.

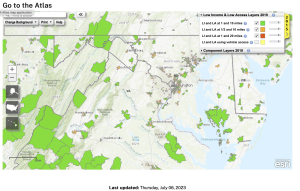

The following map shows the food deserts in Virginia. Rural food deserts can cover large expanses. Rural areas often lack local grocery stores or public transportation to major towns with stores. Some of my students have reported drives to store in excess of 25 miles. You can go to this Food Access Research Atlas map online and figure out whether your particular area shows a food desert and where it might be.

Source: Source: USDA Food Access Research Atlas

The following two maps show the consequences of uneven distribution of food: undernourishment in a world that would have enough food if distribution were simplified primarily in lower income countries.

Source: “Percentage population undernourished world map” by Fnweirkmnwperojvnu via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

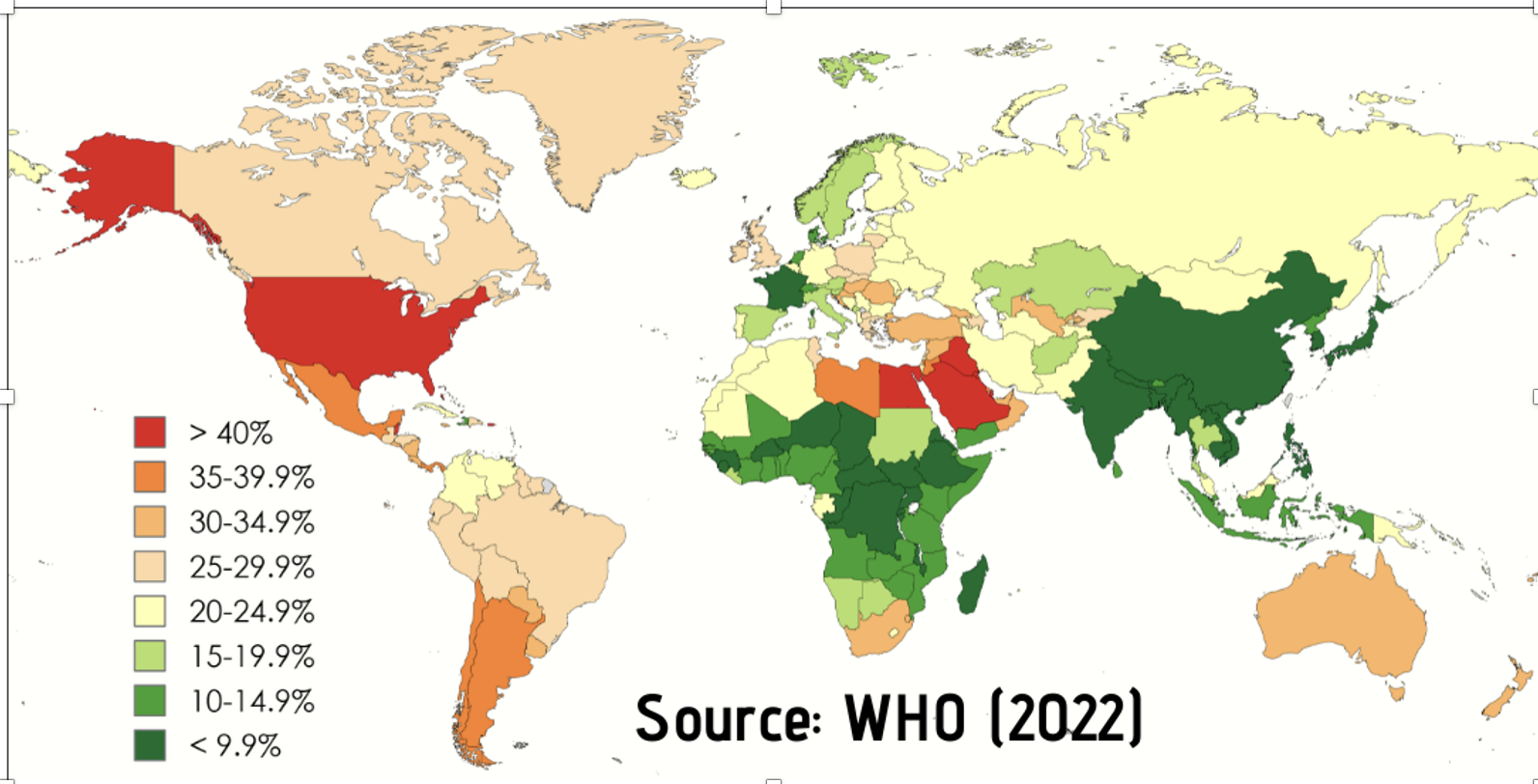

Food distribution within any country is often quite uneven. In areas where people have sufficient funds to purchase affordable meals, there is a tendency to choose unhealthy foods. This is because inexpensive food options are often processed and high in calories, fats, sugars, and sodium, making them less nutritious. As a result, even in wealthier regions, dietary habits can be poor due to the availability and consumption of low-cost, unhealthy food choices. This disparity highlights the complex relationship between economic status, food accessibility, and dietary health within a nation.

Source: “Obesity rate (WHO, 2022)” by Ly.n0m via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 4.0.