11 Group Communication

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- Define what constitutes a group and team.

- Understand cultural influences on groups.

- Explain how groups and teams form.

- Identify group roles and norms.

- Understand different styles of leadership in groups.

- Recognize style and options for decision making in groups.

- Explain the impact of technology on group communication.

Have you ever had this happen to you in a college class? At the beginning of the semester your professor hands out the syllabus and explains that a group project is part of the course requirements. You, and others in the class, groan at the idea of this project because you have experienced the difficulties and frustrations of working in a group, especially when your grade depends on the work of others. Does this sound familiar? Why do you think so many students react negatively to these types of assignments? Group work can be fraught with complications. But, the reality is, many companies are promoting groups as the model working environment (Forbes).

“When I die, I would like the people I did group projects with to lower me in to my grave so they can let me down one last time.” – Jessica Clydesdale, frustrated student.

Chances are that a class assignment is not your first and only experience with groups. Most likely, you have already spent, and will continue to spend, a great deal of your time working in groups. You may be involved with school athletics in which you are part of a specialized group called a team. You may be part of a work or professional group. Many of you participate in social, religious, and/or political groups. The family in which you were raised, regardless of the configuration, is also a group. No matter what the specific focus—sports, profession, politics, or family—all groups share some common features.

While group communication is growing in popularity and emphasis, both at the academic and corporate levels, it is not a new area of study. The emergence of group communication study came about in the mid 1950s, following World War II, and has been a focus of study ever since. Group communication is often closely aligned with interpersonal communication and organizational communication which is why we have placed it as a chapter in between these two areas of specialization. In your personal, civic, professional lives, you will engage in group communication. Let’s take a look at what constitutes a group or team.

Defining Groups and Teams

To understand group and team communication, we must first understand the definition of a group. Many people think that a group is simply a collection of people, but that is only part of it. If you walk out your front door and pull together the first ten people you see, do you have a group? No! According to Wilson and Hanna, groups are defined as, “a collection of three or more individuals who interact about some common problem or interdependent goal and can exert mutual influence over one another” (14). They go on to say that the three key components of groups are, “size, goal orientation, and mutual influence” (14). Interpersonal communication is often thought about in terms of dyads, or pairs. Organizational communication might be thought of as a group that is larger than 12 people. While there are exceptions, for the most part, group size is often thought of in terms of 3-12 people.

Case In Point

Astronaut Jim Lovell’s words during the Apollo 13 lunar mission, “Houston, we have a problem,” launched a remarkable tale of effective teamwork and creative problem solving by NASA engineers working to try to save the lives of the jeopardized crew when two oxygen tanks exploded en route to the moon. Details of the dramatic and successful resolution to the problem became widely known in the motion picture Apollo 13, but it’s not just during dramatic moments when the importance of good teamwork is needed or recognized. In fact, some form of team-oriented work is encouraged in most, if not all, organizations today (Hughes, Jones). So if you feel this is unimportant to know, remember that group communication and teamwork skills are critical for your success later in life.

For example, Joseph Bonito, a Communication professor at the University of Arizona, allows no more than five people in a group to ensure that everyone’s opinions are reflected equally in a discussion. (Baughman and Everett-Haynes). According to Bonito, if there are too many people in a group it’s possible that some individuals will remain silent without anyone noticing. He suggests using smaller groups when equal participation is desirable. So, if the ten people you gathered outside of your front door were all neighbors working together as part of a “neighborhood watch” to create safety in the community, then you would indeed have a group.

For those of you who have participated on athletic teams you’ll notice that these definitions also apply to a team. While all of the qualities of groups hold true for teams, teams have additional qualities not necessarily present for all groups. We like to define a team as a specialized group with a strong sense of belonging and commitment to each other that shapes an overall collective identity. Members of a team each have their own part, or role, to fulfill in order to achieve the team’s greater goals. One member’s strengths can be other member’s weaknesses, so working in a team is beneficial when balancing individual input. Take a football team, for example: While all teammates share some degree of athletic ability as well as an appreciation for the sport, each member has a highly specialized skill as indicated in the various positions on the team—quarterback, receiver, and running back. In addition to athletic teams, work and professional teams also share these qualities. Now that you know how to define groups and teams, let’s look at characteristics of groups and teams, as well as the different types of groups and teams.

Characteristics of Groups

What makes groups different than interpersonal communication, organizational communication, or simply talking with a group of friends at dinner? Below we outline characteristics that make groups distinct in terms of their communication.

- Interdependence. Groups cannot be defined simply as three or more people talking to each other or meeting together. Instead, a primary characteristic of groups is that members of a group are dependent on the others for the group to maintain its existence and achieve its goals. In essence, interdependence is the recognition by those in a group of their need for the others in the group (Lewin; Cragon, Wright& Kasch; Sherblom). Imagine playing in a basketball game as an individual against the five members of another team. Even if you’re considered the best basketball player in the world, it’s highly unlikely you could win a game against five other people. You must rely on four other teammates to make it a successful game.

- Interaction. It probably seems obvious to you that there must be interaction for groups to exist. However, what kind of interaction must exist? Since we all communicate every day, there must be something that distinguishes the interaction in groups from other forms of communication. Cragon, Wright and Kasch state that the primary defining characteristic of group interaction is that it is purposeful. They go on to break down purposeful interaction into four types: problem solving, role playing, team building, and trust building (7). Without purposeful interaction a true group does not exist. Roles, norms, and relationships between members are created through interaction. If you’re put into a group for a class assignment, for example, your first interaction probably centers around exchanging contact information, settings times to meet, and starting to focus on the task at hand. It’s purposeful interaction in order to achieve a goal.

“Brittensinfonia concert” by Leftblank , Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Group Communication Then

The first study that was published on group communication in the New School era of communication study was credited to Edwin Black in 1955. He studied the breakdowns in group interactions by looking at communication sequences in groups. However, it wasn’t until the 1960s and 70s that a large number of studies in group communication began to appear. Between 1970 and 1978 114 articles were published on group communication and 89 more were published by 1990 (Stacks & Salwen 360). Study in group communication is still important over a decade later as more and more organizations focus on group work for achieving their goals.

- Synergy. One advantage of working in groups and teams is that they allow us to accomplish things we wouldn’t be able to accomplish on our own. Remember back to our discussion of Systems Theory in Chapter 5. Systems Theory suggests that “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” This is the very idea of synergy (Sherblom). In an orchestra or band, each person is there to perform in order to help the larger unit make music in a way that cannot be accomplished without each member working together.

- Common Goals. Having interaction and synergy would be relatively pointless in groups without a common goal. People who comprise groups are brought together for a reason or a purpose. While most members of a group have individual goals, a group is largely defined by the common goals of the group. Think of the example at the beginning of the chapter: Your common goal in a class group is to learn, complete an assignment, and earn a grade. While there may be differences regarding individual goals in the group (what final grade is acceptable for example), or how to achieve the common goals, the group is largely defined by the common goals it shares.

- Shared Norms. Because people come together for a specific purpose, they develop shared norms to help them achieve their goals. Even with a goal in place, random interaction does not define a group. Group interaction is generally guided by norms a group has established for acceptable behavior. Norms are essentially expectations of the group members, established by the group and can be conscious and formal, or unconscious and informal. A couple of examples of group norms include the expectation that all members show up at group meeting times, the expectation that all group members focus on the group instead of personal matters (for example, turning cell phones and other distractions off), and the expectation that group members finish their part of the work by the established due date. When members of the group violate group norms, other members of the group get frustrated and the group’s overall goal may be affected.

- Cohesiveness. One way that members understand of the idea of communicating in groups and teams is when they experience a sense of cohesiveness with other members of the group. When we feel like we are part of something larger, we experience a sense of cohesion or wholeness, and may find a purpose that is bigger than our own individual desires and goals. It is the sense of connection and participation that characterizes the interaction in a group as different from the defined interaction among loosely connected individuals. If you’ve ever participated in a group that achieved its goal successfully, you are probably able to reflect back on your feelings of connections with the other members of that group.

You may be asking yourself, what about teams? We have focused primarily on groups, but it’s critical to remember the importance of team communication characteristics as well as group communication characteristics. Check out this article that breaks down team characteristics and skills that ensure team success (we bet you’ll find similarities to the group characteristics that we have just explained).

Types of Groups

Not all groups are the same or brought together for the same reasons. Brilhart and Galanes categorize groups “on the basis of the reason they were formed and the human needs they serve” (9). Let’s take a look!

- Primary Groups. Primary groups are ones we form to help us realize our human needs like inclusion and affection. They are not generally formed to accomplish a task, but rather, to help us meet our fundamental needs as relational beings like acceptance, love, and affection. These groups are generally longer term than other groups and include family, roommates, and other relationships that meet as groups on a regular basis (Brilhart & Galanes). These individuals in your life tend to offer love and support on a meaningful level, and therefore constitute primary groups. Given this factor, primary groups are typically more significant than secondary groups.

- Secondary Groups. Unlike primary groups, we form secondary groups to accomplish work, perform a task, solve problems, and make decisions (Brilhart & Galanes; Sherblom; Cragan, Wright & Kasch). Larson and LaFasto state that secondary groups have “a specific performance objective or recognizable goal to be attained; and coordination of activity among the members of the team is required for attainment of the team goal or objective” (19). An example of this would be a group of students coming together to volunteer at a soup kitchen for Thanksgiving. With so many people that need to be served, it takes coordination and a team mentality for the operation to run smoothly.

- Activity Groups. Activity Groups are ones we form for the purpose of participating in activities. I’m sure your campus has many clubs that are organized for the sole purpose of doing activities. For example, your campus probably has a debate team that meets regularly for the sole purpose of engaging in debates about relevant topics and broadening their own personal knowledge and experience. If it weren’t for that context, the team would have no other reason for meeting.

- Personal Growth Groups. We form Personal Growth Groups to obtain support and feedback from others, as well as to grow as a person. Personal Growth Groups may be thought of as therapy groups. An example that is probably familiar to you is Alcoholics Anonymous, where alcoholics can share their stories and struggles and get support from others affected by alcohol. There are many personal growth groups available for helping us develop as people through group interaction with others, such as book clubs, weight watchers, and spiritual groups.

- Learning Groups. Learning Groups focus mainly on obtaining new information and gaining knowledge. If you have ever been assigned to a group in a college class, it most likely was a learning group with the purpose of interacting in ways that can help those in the group learn new things about the course content.

- Problem-Solving Groups. These groups are created for the express purpose of solving a specific problem. The very nature of organizing people into this type of group is to get them to collectively figure out effective solutions to the problem they have before them. Committees are an excellent example of people who are brought together to solve problems. A great example would be the on-campus group, Check It, which takes action in preventing harm caused by sexual assault.

After looking at the various types of groups, it’s probably easy for you to recognize just how much of your daily interaction occurs within the contexts of groups. The reality is, we spend a great deal of time in groups, and understanding the types of groups you’re in, as well as their purpose, goes a long way toward helping you function as a productive member.

The Importance of Studying Communication in Groups and Teams

One of the reasons communication scholars study groups and teams is because of the overwhelming amount of time we spend interacting in groups in professional contexts. More and more professional organizations are turning to groups and teams as an essential way of conducting business and getting things done. Even professions that are seemingly independent, such as being a college professor, are heavily laden with group work. The process of writing this book was a group effort as the authors and their students worked in groups to bring the book to you. Each of us had specific roles and tasks to perform.

Another vital area of group communication concerns the study of social change or social movement organizations. Groups such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the National Organization of Women (NOW) are all groups bound together by a shared social and political commitment—-to promote the rights of nonhuman animals, African-Americans, and women respectively. While individuals can be committed to these ideas, the social, political, and legal rights afforded to groups like these would not have been possible through individual action alone. It was when groups of like-minded people came together with shared commitments and goals, pooling their skills and resources, that change occurred. Just about any Interest Group you can think of has a presence in Washington D.C. and spends money to maintain that presence. Visit here for more information on Interest Groups.

The study of social movements reveals the importance of groups for accomplishing goals. Bowers, Ochs, Jensen and Schulz, in The Rhetoric of Agitation and Control, explain seven progressive and cumulative strategies through which movements progress as they move toward success. Three of the seven strategies focus explicitly on group communication—-promulgation, solidification, and polarization. Promulgation refers to the “a strategy where agitators publicly proclaim their goals and it includes tactics designed to win public support” (23). Without a sufficient group the actions of individual protestors are likely to be dismissed. The strategy of solidification “occurs mainly inside the agitating group” and is “primarily used to unite followers” (29). The point is to unite group members and provide sufficient motivation and support. The communication that occurs through the collective action of singing songs or chanting slogans serves to unite group members. Because the success of social movements depends in part on the ability to attract a large number of followers, most employ the strategy of polarization, which is designed to persuade neutral individuals or “fence sitters” to join a group (40). The essence of this strategy is captured in the quote from Eldridge Cleaver, “You are either part of the problem or part of the solution.” Taken together these three strategies stress that the key to group success is the sustained effort of group members working together through communication.

Case In Point

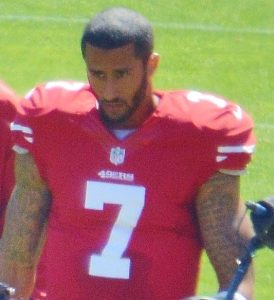

#Take A Knee

On August 27th, Colin Kaepernick, player for the 49ers, drew attention when he took a knee during the National Anthem to display his protest for the injustices faced by African Americans in the USA, namely, police brutality. Though he was fired from his team and the form of protest was thought to be dismantled, many athletes began showing their solidarity to him and the movement by also taking a knee during the National Anthem. This display of group solidarity was incredibly powerful and continues to be a large topic of debate. This social movement effectively displays the strategies of agitation as mentioned above: Promulgation, Solidification, and Polarization, and has only garnered its strength through the unity of athletes prepared to voice their support for a cause.

Not only do Communication scholars focus on work and social movements, we are also interested in the role that one’s cultural identity and membership plays in our communicative choices, and how we interpret the communication of others. This focus sheds interesting insights when we examine membership and communication in groups and teams. One reason for this is that different cultures emphasize the role of individuals while other cultures emphasize the importance of the group. For example, collectivist cultures are ones that place high value on group work because they understand that outcomes of our communication impact all members of the community and the community as a whole, not just the individuals in the group. Conversely, individualistic cultures are ones that place high value on the individual person above the needs of the group. Thus, whether we view group work as favorable or unfavorable may stem from our cultural background. The U.S. is considered an individualistic culture in that we value the work and accomplishments of the individual through ideals such as being able to “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” and create success for yourself.

Power in Groups

Given the complexity of group interaction, it’s short-sighted to try to understand group communication without looking at notions of power (think back to Critical Theories and Research Methods). Power influences how we interpret the messages of others and determines the extent to which we feel we have the right to speak up and voice our concerns and opinions to others. Take a moment to reflect on the different ways you think about power. What images come to mind for you when you think of power? Are there different kinds of power? Are some people inherently more powerful than others? Do you consider yourself to be a powerful person? We highlight three ways to understand power as it relates to group and team communication. The word “power” literally means “to be able” and has many implications.

If you associate power with control or dominance, this refers to the notion of power as power-over. According to Starhawk, “power-over enables one individual or group to make the decisions that affect others, and to enforce control” (9). Control can and does take many forms in society. Starhawk explains that,

- This power is wielded from the workplace, in the schools, in the courts, in the doctor’s office. It may rule with weapons that are physical or by controlling the resources we need to live: money, food, medical care; or by controlling more subtle resources: information, approval, love. We are so accustomed to power-over, so steeped in its language and its implicit threats, that we often become aware of its functioning only when we see its extreme manifestations. (9)

When we are in group situations and someone dominates the conversation, makes all of the decisions, or controls the resources of the group such as money or equipment, this is power-over.

Power-from-within refers to a more personal sense of strength or agency. Power-from-within manifests itself when we can stand, walk, and speak “words that convey our needs and thoughts” (Starhawk 10). In groups, this type of power “arises from our sense of connection, our bonding with other human beings, and with the environment” (10). As Heider explains in The Tao of Leadership, “Since all creation is a whole, separateness is an illusion. Like it or not, we are team players. Power comes through cooperation, independence through service, and a greater self through selflessness” (77). If you think about your role in groups, how have you influenced other group members? Your strategies indicate your sense of power-from-within.

Finally, groups manifest power-with, which is “the power of a strong individual in a group of equals, the power not to command, but to suggest and be listened to, to begin something and see it happen” (Starhawk 10). For this to be effective in a group or team, at least two qualities must be present among members: 1) All group members must communicate respect and equality for one another, and 2) The leader must not abuse power-with and attempt to turn it into power-over. Have you ever been involved in a group where people did not treat each others as equals or with respect? How did you feel about the group? What was the outcome? Could you have done anything to change that dynamic?

Communication is the cornerstone of any group, where group members utilize it to organize and maintain groups. We all have experienced being a part of a group. How are groups formed, and under what circumstances?

Forming Groups

Sometimes we join a group because we want to. Other times, we might be assigned to work in groups in a class or at work. Whether we like it or not, groups are a significant and unavoidable factor of life. Lumsden, Lumsden and Wiethoff give three reasons why we form groups. First, we may join groups because we share similar interests or attractions with other group members. When taking courses that pertain to your chosen college major, chances are you share some of the same interests as your classmates. Likewise, you might find yourself attracted to others in your group for romantic, friendship, political, religious or professional reasons. On our campus, our majors have formed the Communication Club to bring together students in the major. Though students within the group come from a diverse variety of backgrounds, they are able to bond through their shared studies and interests.

A second reason we join groups is called drive reduction. Essentially, we join groups so our work with others reduces the drive to fulfill our needs by spreading out involvement. As Maslow explains, we have drives for physiological needs like security, love, self-esteem, and self-actualization. Working with others helps us achieve these needs thereby reducing our obligation to meet these needs ourselves (Maslow; Paulson). If you accomplished a task successfully for a group, your group members likely complimented your work, thus fulfilling some of your self-esteem needs. If you had done the same work only for yourself, the building up of your self-esteem may not have occurred. A third reason we join groups is for reinforcement. We are often motivated to do things for the rewards they bring. Participating in groups provides reinforcement from others in the pursuit of our goals and rewards.

Much like interpersonal relationships, groups go through a series of stages as they come together. These stages are called forming, storming, norming, and performing (Tuckman; Fisher; Sherblom; Benson; Rose, Hopthrow & Crisp). Groups that form to achieve a task often go through a fifth stage called termination that occurs after a group accomplishes its goal. Let’s look at each of the stages of group formation and termination.

- Forming. Obviously, for a group to exist and work together its members must first form the group. During the forming stage, group members begin to set the parameters of the group by establishing what characteristics identify the members of the group as a group. During this stage, the group’s goals are made generally clear to members, initial questions and concerns are addressed, and initial role assignments may develop. This is the stage when group norms begin to be negotiated and established. Essentially, norms are a code of conduct which may be explicit or assumed and dictate acceptable and expected behavior of the group.

- Storming. The storming stage might be considered comparable to the “first fight” of a romantic couple. After the initial politeness passes in the forming stage, group members begin to feel more comfortable expressing their opinions about how the group should operate and the participation of other members in the group. Given the complexity of meeting both individual goals as well as group goals, there is constant negotiation among group members regarding participation and how a group should operate. Imagine being assigned to a group for class and you discover that all the members of the group are content with getting a C grade, but you want an A. If you confront your group members to challenge them to have higher expectations, you are in the storming stage.

- Norming. Back to our romantic couple example, if the couple can survive the first fight, they often emerge on the other side of the conflict feeling stronger and more cohesive. The same is true in groups. If a group is able to work through the initial conflict of the storming stage, there is the opportunity to really solidify the group’s norms and get to the task at hand as a cohesive group. Norming signifies that the members of a group are willing to abide by group rules and values to achieve the group’s goals.

- Performing. Performing is the stage we most often associate as the defining characteristic of groups. This stage is marked by a decrease in tensions, less conscious attention to norm establishment, and greater focus on the actual work at hand in order to accomplish the group’s goals. While there still may be episodes of negotiating conflict and re-establishing norms, performing is about getting to the business at hand. When you are in a weekly routine of meeting at the library to work on a group project, you are in the performing stage.

- Terminating. Groups that are assigned a specific goal and timeline will experience the fifth stage of group formation, termination. Think about groups you have been assigned to in college. We’re willing to bet that the group did not continue once you achieved the required assignment and earned your grade. This is not to say that we do not continue relationships with other group members. But, the defining characteristics of the group established during the forming stage have come to an end, and thus, so has the group.

Group Communication Now

Technology is changing so many things about the ways we communicate. This is also true in group communication. One of the great frustrations for many people in groups is simply finding a time that everyone can meet together. However, computer technology has changed these dynamics as more and more groups “meet” in the virtual world, rather than face-to-face. But, what is the impact of technology on how groups function? Dr. Kiran Bala argues that “new media has brought a sea of changes in intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, and mass communication processes and content.” With group chat available on almost all social media networks and numerous technological devices, we have a lot to learn about the ways communication technologies are changing our notions of working in groups and individual communication styles.

Now that you understand how groups form, let’s discuss the ways in which people participate in groups. Since groups are comprised of interdependent individuals, one area of research that has emerged from studying group communication is the focus on the roles that we play in groups and teams. Having an understanding of the various roles we play in groups can help us understand how to interact with various group members.

Groups Roles

Take a moment to think about the individuals in a particular group you were in and the role each of them played. You may recall that some people were extremely helpful, organized and made getting the job done easy. Others may have been more difficult to work with, or seemed to disrupt the group process. In each case, the participants were performing roles that manifest themselves in most groups. Early studies on group communication provide an overwhelming number of different types of group roles. To simplify, we provide an overview of some of the more common roles. As you study group roles, remember that we usually play more than one role at a time, and that we do not always play the same roles from group to group.

We organize group roles into four categories—task, social-emotional, procedural, and individual. Task roles are those that help or hinder a group’s ability to accomplish its goals. Social-emotional roles are those that focus on building and maintaining relationships among individuals in a group (the focus is on how people feel about being in the group). Procedural roles are concerned with how the group accomplishes its task. People occupying these roles are interested in following directions, proper procedure, and going through appropriate channels when making decisions or initiating policy. The final category, individual roles, includes any role “that detracts from group goals and emphasizes personal goals” (Jensen & Chilberg 97). When people come to a group to promote their individual agenda above the group’s agenda, they do not communicate in ways that are beneficial to the group. Let’s take a look at each of these categories in more detail.

- Task Roles. While there are many task roles a person can play in a group, we want to emphasize five common ones. The Task Leader is the person that keeps the group focused on the primary goal or task by setting agendas, controlling the participation and communication of the group’s members, and evaluating ideas and contributions of participants. Your associated students president probably performs the task leader role. Information Gatherers are those people who seek and/or provide the factual information necessary for evaluating ideas, problem solving, and reaching conclusions. This is the person who serves as the liaison with your professors about what they expect from a group project. Opinion Gatherers are those that seek out and/or provide subjective responses about ideas and suggestions. They most often take into account the values, beliefs, and attitudes of members. If you have a quiet member of your group, the opinion gatherer may ask, “What do you think?” in order to get that person’s feedback. The Devil’s Advocate is the person that argues a contrary or opposing point of view. This may be done positively in an effort to ensure that all perspectives are considered, or negatively as the unwillingness of a single person to participate in the group’s ideas. The Energizer is the person who functions as the group’s cheer-leader, providing energy, motivation, and positive encouragement.

- Social-Emotional Roles. Group members play a variety of roles in order to build and maintain relationships in groups. The Social-Emotional Leader is the person who is concerned with maintaining and balancing the social and emotional needs of the group members and tends to play many, if not all, of the roles in this category. The Encourager practices good listening skills in order to create a safe space for others to share ideas and offer suggestions. Followers are group members that do what they are told, going along with decisions and assignments from the group. The Tension Releaser is the person that uses humor, or can skillfully change the subject in an attempt to minimize tension and avoid conflict. The Compromiser is the one who mediates disagreements or conflicts among members by encouraging others to give in on small issues for the sake of meeting the goals of the group. What role do you find yourself most likely to enact in groups? Or, do you find you switch between these roles depending on the group?

- Procedural Roles. Groups cannot function properly without having a system of rules or norms in place. Members are responsible for maintaining the norms of a group and play many roles to accomplish this. The Facilitator acts like a traffic director by managing the flow of information to keep the group on task. Gatekeepers are those group members that attempt to maintain proper communicative balance. These people also serve as the points of contact between times of official group meetings. The Recorder is the person responsible for tracking group ideas, decisions, and progress. Often, a written record is necessary, thus, this person has the responsibility for keeping, maintaining, and sharing group notes. If you’re the person who pulls out a pen and paper in order to track what the group talks about, you’re the recorder.

Case-in-Point

The popular sitcom Workaholics (2011-present) follows three college drop-outs who work in a telemarketing company and are notoriously terrible workers. Always working as a group in their shared cubicle, the three young men are all prime examples of group members who play Individual Roles: Anders as the Aggressor, Blake as the Self-Confessor, Adam as the Blocker, and all three of them as the joker or clown at one point or another. As you might guess, this group is very unproductive and ineffective.

- Individual Roles. Because groups are made of individuals, group members often play various roles in order to achieve individual goals. The Aggressor engages in forceful or dominating communication to put others down or initiate conflict with other members. This communication style can cause some members to remain silent or passive. The Blocker is the person that fusses or complains about small procedural matters, often blocking the group’s progress by not letting them get to the task. They worry about small details that, overall, are not important to achieving the group’s desired outcome. The Self-Confessor uses the group as a setting to discuss personal or emotional matters not relevant to the group or its task. This is the person that views the group as one that is there to perform group therapy. The Playboy or Playgirl shows little interest in the group or the problem at hand and does not contribute in a meaningful way, or at all. This is the person who does essentially no work, yet still gets credit for the group’s work. The Joker or Clown uses inappropriate humor or remarks that can steer the group from its mission.

While we certainly do not have the space to cover every role you might encounter in a group, we’re sure you can point to your own examples of people who have filled the roles we’ve discussed. Perhaps you can point to examples of when you have filled some of these roles yourself. Important for group members to understand, are the various roles they play in groups in order to engage in positive actions that help the group along. One dynamic that these roles contribute to in the process of group communication is leadership in groups. Let’s briefly examine how leadership functions in groups.

Leadership In Groups

While we’ve examined roles we can play in groups, the role that often gets the most attention is that of the leader. Like defining communication, many people have an idea of what a leader is, but can’t really come up with a good definition for the term as there are many ways to conceptualize the role of leader. One way to do this is to think of leaders in terms of their leadership styles. Let’s look at three broad leadership styles to better understand the communication choices leaders can make, as well as the outcome of such choices, in a group.

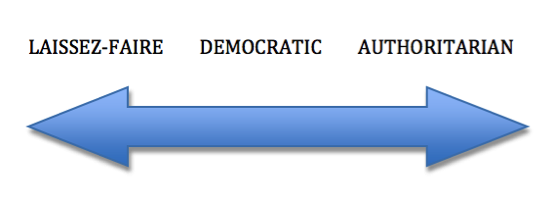

First, let’s visualize leadership styles by seeing them as a continuum. The position to the left (Laissez-faire) indicates a leader who exerts little to no control over a group, while the position on the right (Authoritarian) indicates a leader who seeks complete control. The position in the middle (Democratic) is one where a leader maintains a moderate level of control or influence in a group with the group’s permission (Bass & Stogdill; Berkowitz).

- Laissez-faire is a French term that literally means “let do.” This leadership style is one in which the leader takes a laid back or hands-off approach. For a variety of reasons, leaders may choose to keep their input at a minimum and refrain from directing a group. What do you think some reasons may be for selecting this leadership style? Perhaps a person feels uncomfortable being a leader. Perhaps a person does not feel that she/he possesses the skills required to successfully lead the group. Or, perhaps the group is highly skilled, motivated, and efficient and does not require much formal direction from a leader. If the latter is the case, then a laissez-faire approach may work well. However, if a group is in need of direction then a laissez-faire style may result in frustration and inefficiency. An example of a Laissez-faire leader if Michael Scott from The Office. His laid back attitude and focus on making friends prevents substantial work to occur. The Office is relaxed, unproductive, and distracted by Michael’s shenanigans.

- An authoritarian leadership style is one in which a leader attempts to exert maximum control over a group. This may be done by making unilateral decisions rather than consulting all members, assigning members to specific tasks or duties, and generally controlling group processes. This leadership style may be beneficial when a group is in need of direction or there are significant time pressures. Authoritarian leaders may help a group stay efficient and organized in order to accomplish its goals. However, group members may be less committed to the outcomes of the group process than if they had been a part of the decision making process. One term that you may have heard on your campus is “shared-governance.” In general, faculty do not like working in groups where one person is making the decisions. Instead, most faculty prefer a system where all members of a group share in the leadership process. This can also be called the democratic style of leadership.

- The democratic style of leadership falls somewhere in the middle of laissez-faire and authoritarian styles. In these situations, the decision-making power is shared among group members, not exercised by one individual. In order for this to be effective, group members must spend considerable time sharing and listening to various positions and weighing the effects of each. Groups organized in this fashion may be more committed to the outcomes of the group, creative, and participatory. However, as each person’s ideas are taken into account, this can extend the amount of time it takes for a group to accomplish its goals.

While we’ve certainly oversimplified our coverage of the complex nature of group leaders, you should be able to recognize that there are pros and cons to each leadership style depending on context. There is not one right way to be a leader for every group. Effective leaders are able to adapt their leadership style to fit the needs of the group. Furthermore, as a group’s needs and members change over time, leadership styles can accommodate natural changes in the group’s life cycle. Take a moment to think of various group situations in which each leadership style may be the most and the least desirable. What are examples of groups where each style of leadership could be practiced effectively?

Group Norms

Every group in which we participate has a set of norms like we discussed in the “norming” stage. Each group’s rules and norms are different, and we must learn them to be effective participants. Some groups formalize their norms and rules, while others are less formal and more fluid. Norms are the recognized rules of behavior for group members. Norms influence the ways we communicate with other members, and ultimately, the outcome of group participation. Norms are important because, as we highlighted in the “norming” stage of group formation, they are the defining characteristics of groups.

Brilhart and Galanes divide norms into two categories. General norms “direct the behavior of the group as a whole” (130). Meeting times, how meetings run, and the division of tasks are all examples of general norms that groups form and maintain. These norms establish the generally accepted rules of behavior for all group members. The second category of norms is role-specific norms. Role-specific norms “concern individual members with particular roles, such as the designated leader” (130).

Not only are there norms that apply to all members of a group, there are norms that influence the behaviors of each role. Consider our brief discussion on leadership. If a group’s members are self-motivated, and do not need someone imposing structure, they will set a norm that the group leader should act as a laissez-faire or democratic leader rather than an authoritarian leader. Violation of this norm would most likely result in conflict if leaders try to impose their will. A violation like this will send a group back to the “storming” stage to renegotiate the acceptable norms of the group. When norms are violated, group members most often will work to correct the violation to get the group back on task and functioning properly. Have you ever been in a group in which a particular group member did not do the task that was assigned to them? What happened? How did the group handle this situation as a whole? What was the response of the person who did not complete the task? In hindsight, would you have handled it differently? If so, how?

As groups progress through the various stages, and as members engage in the various roles, the group is in a continual process of decision making. Since this is true, it makes sense to ask the question, “How is it that groups make decisions?”

Decision Making In Groups

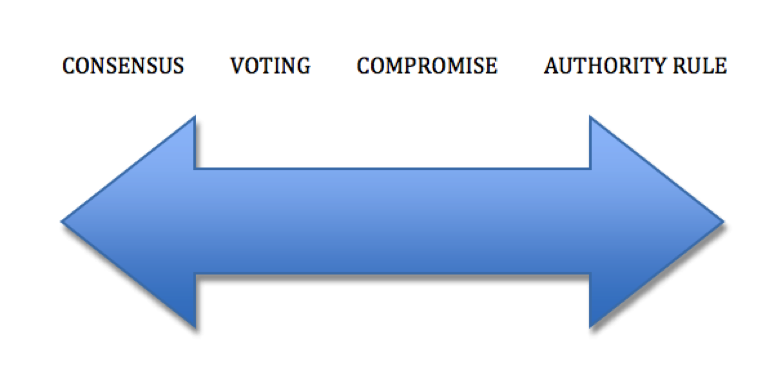

When groups need to get a job done they should have a method in place for making decisions. The decision making process is a norm that may be decided by a group leader or by the group members as a whole. Let’s look at four common ways of making decisions in groups. To make it simple we will again use a continuum as a way to visualize the various options groups have for making decisions. On the left side are those methods that require maximum group involvement (consensus and voting). On the right are those methods that use the least amount of input from all members (compromise and authority rule).

The decision-making process that requires the most group input is called consensus. To reach consensus group members must participate in the crafting of a decision and agree to adopt it. While not all members may support the decision equally, all will agree to carry it out. In individualistic cultures like the U.S., where a great deal of value is placed on independence and freedom of choice, this option can be seen by group members as desirable, since no one is forced to go along with a policy or plan of action to which they are opposed. Even though this style of decision making has many advantages, it has its limitations as well—it requires a great deal of creativity, trust, communication, and time on the part of all group members. When groups have a hard time reaching consensus, they may opt for the next strategy which does not require buy-in from all or most of the group.

Group Communication and You

Okay, you’re a Communication major and this whole idea of working in groups really appeals to you and seems to come naturally. But perhaps you’re not a Communication major and you’re thinking to yourself that your future career isn’t really going to require group or team work. Well, you might want to think again. Forbes magazine released an article titled The Ten Skills Employers Most Want in 2015 Graduates which stated that technical knowledge related to the job is not nearly as important as effective teamwork and communications skills. In fact, the top three skills listed include, 1) ability to work in a team structure, 2) ability to make decisions and solve problems, and 3) ability to communicate verbally with people inside and outside an organization. Even non-Communication majors need to develop effective group communication skills to succeed at work.

Even non-Communication majors need to develop effective group communication skills to succeed at work.

Voting by majority may be as simple as having 51% of the vote for a particular decision, or may require a larger percentage, such as two-thirds or three-fourths, before reaching a decision. Like consensus, voting is advantageous because everyone is able to have an equal say in the decision process (as long as they vote). Unlike consensus, everyone may not be satisfied with the outcome. In a simple majority, 49% of voters may be displeased and may be resistant to abide by the majority vote. In this case the decision or policy may be difficult to carry out and implement. For example, our campus recently had a department vote on whether or not they wanted to hire a particular person to be a professor. Three faculty voted yes for the person, while two faculty voted no. Needless to say, there was a fair amount of contention among the professors who voted. Ultimately, the person being considered for the job learned about the split vote and decided that he did not want to take the job because he felt that the two people that voted no would not treat him well.

Toward the right of our continuum is compromise. This method often carries a positive connotation in the U.S. because it is perceived as fair since each member gives up something, as well as gains something. Nevertheless, this decision making process may not be as fair as it seems on the surface. The main reason for this has to do with what is being given up and obtained. There is nothing in a compromise that says these two factors must be equal (that may be the ideal, but it is often not the reality). For individuals or groups that feel they have gotten the unfair end of the bargain, they may be resentful and refuse to carry out the compromise. They may also foster ill will toward others in the group, or engage in self-doubt for going along with the compromise in the first place. However, if groups cannot make decisions through consensus or voting, compromise may be the next best alternative.

At the far right of our continuum is decision by authority rule. This decision-making process requires essentially no input from the group, although the group’s participation may be necessary for implementing the decision. The authority in question may be a member of the group who has more power than other members, such as the leader, or a person of power outside the group. While this method is obviously efficient, members are often resentful when they feel they have to follow another’s orders and feel the group process was a façade and waste of valuable time.

During the decision making process, groups must be careful not to fall victim to groupthink. Groupthink happens when a group is so focused on agreement and consensus that they do not examine all of the potential solutions available to them. Obviously, this can lead to incredibly flawed decision making and outcomes. Groupthink occurs when members strive for unanimity, resulting in self-deception, forced consent, and conformity to group values and ethics (Rose, Hopthrow & Crisp). Many people argue that groupthink is the reason behind some of history’s worst decisions, such as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, The Pearl Harbor attack, The North Korea escalation, the Vietnam escalation, and the Bush administration’s decision to go to war with Iraq (Rose, Hopthrow & Crisp). Let’s think about groupthink on a smaller, less detrimental level. Imagine you are participating in a voting process during a group meeting where everyone votes yes on a particular subject, but you want to vote no. You might feel pressured to conform to the group and vote yes for the sole purpose of unanimity, even though it goes against your individual desires.

As with leadership styles, appropriate decision making processes vary from group to group depending on context, culture, and group members. There is not a “one way fits all” approach to making group decisions. When you find yourself in a task or decision-making group you should consider taking stock of the task at hand before deciding as a group the best ways to proceed.

Group Work and Time

By now you should recognize that working in groups and teams has many advantages. However, one issue that is of central importance to group work is time. When working in groups time can be both a source of frustration, as well as a reason to work together. One obvious problem is that it takes much longer to make decisions with two or more people as opposed to just one person. Another problem is that it can be difficult to coordinate meeting times when taking into account people’s busy lives of work, school, family, and other personal commitments. On the flip side, when time is limited and there are multiple tasks to accomplish, it is often more efficient to work in a group where tasks can be delegated according to resources and skills. When each member can take on certain aspects of a project, this limits the amount of work an individual would have to do if he/she were solely responsible for the project.

For example, Alex, Kellsie and Teresa all had a project to work on. The project was large and would take a full semester to complete. They had to split up the amount of work equally to each person as well as based on skills. The thought of doing all the work alone was daunting in terms of the required time and labor. Being able to delegate assignments and work together to achieve a professional result for their project indicated that the best option for them was to work together. In the end, the group’s work produced different results and views that you wouldn’t have necessarily come to working alone. On the flip side, imagine having to work in a group where you believe you could do just the same on your own. When deciding whether or not to work in groups, it is important to consider time. Is the time and effort of working in a group worth the outcome? Or, is it better to accomplish the task as an individual?

Groups and Technology and Social Media

Social media and technology are changing the ways we communicate in groups. There is no doubt that technology is rapidly changing the ways we communicate in a variety of contexts, and group communication is no exception. Many organizations use computers and cell phones as a primary way to keep groups connected given their ease of use, low cost, and asynchronous nature. In fact, it’s likely that your course web pages also have “group forums” for class groups to deal with the complexities of finding times to meet. In fact, the group that worked on this chapter used Google Docs to have live chats online, transfer documents back and forth, and form messages to achieve the group’s goals–all without ever having to meet in person. As you enter the workforce, you’ll likely find yourself participating in virtual groups with people who have been brought together from a variety of geographical locations.

Group Communication and You

Today, we know that social media has the power to bring people together and drive change. Sports fans flock to Twitter and other social media outlets to follow their favorite teams and athletes. Less than 5 percent of TV is sport, but 50 percent of what is tweeted is about sports. And if there was any thought that this phenomenon was only for Americans that is quickly debunked by the worldwide usage statistics.

“The power to create the global sports village and encourage the next generation of pro-social media sports fans is at our fingertips.” -Adam C. Earnheardt

While communication technologies can be beneficial for bringing people together and facilitating groups, they also have drawbacks. When we lack face-to-face encounters, and rely on asynchronous forms of communication, there is greater potential for information to be lost and messages to be ambiguous. The face-to-face nature of traditional group meetings provides immediate processing and feedback through the interaction of group members. When groups communicate through email, threads, discussion forums, text messaging, etc., they lose the ability to provide immediate feedback to other members. Also, using communication technologies takes a great deal more time for a group to achieve its goals due to the asynchronous nature of these channels.

Nevertheless, technology is changing the ways we understand groups and participate in them. We have yet to work out all of the new standards for group participation introduced by technology. Used well, technology opens the door for new avenues of working in groups to achieve goals. Used poorly, technology can add to the many frustrations people often experience working in groups and teams.

Summary

We participate in groups and teams at all stages and phases of our lives, from play groups, to members of an athletic team, to performing in a band, or performing in a play. We form groups based on personal and professional interests, drive reduction, and for reinforcement. Through group and team work we can save time and resources, enhance the quality of our work, succeed professionally, or accomplish socio-political change.

As you recall, a group is composed of three or more people who interact over time, depend on each other, and follow shared rules and norms. A team is a specialized group which possesses a strong sense of collective identity and compatible and complimentary resources. There are five general types of groups depending on the intended outcome. Primary groups are formed to satisfy our long-term emotive needs. Secondary groups are more performance based and concern themselves with accomplishing tasks or decision making. Personal growth groups focus on specific areas of personal problem solving while providing a supportive and emotionally positive context. Learning groups are charged with the discovery and dissemination of new ideas while problem solving groups find solutions.

Once a group comes together they go through typical stages (forming, storming, norming, performing, and terminating) to develop roles, create a leadership strategy, and determine the process for decision making. While numerous specific group roles exit, the four categories of roles include: task, social-emotional, procedural, and individual roles. It is likely that members will occupy multiple roles simultaneously as they participate in groups.

There are three broad leadership styles ranging from least to most control—laissez faire, democratic, and authoritarian. Also related to power and control are options for decision making. Consensus gives members the most say, voting and compromise may please some but not others, and authority rule gives all control to the leader. None of the options for leadership styles and decision making are inherently good or bad—the appropriate choice depends on the individual situation and context. It is important for groups not to become victims of groupthink as they make decisions.

New technologies are continually changing how we engage in group communication. The asynchronous nature of communication technologies can facilitate group processes. However, they also have the potential to slow groups down and make it more difficult to accomplish group goals.

Discussion Questions

- What are the differences between the terms “team” and “group?” Write down a team you have been a part of and a group you have been a part of. In what ways were they effective or not effective?

- Review all the different types of group roles. Reflect back on a time when you worked in a group and discuss the role(s) you played. If there were any individuals in this group that prevented the group’s progress, identify their role and explain why it was problematic.

- Think of all the groups you participate in and the roles you take on. Do different groups call for different variations of roles? Do you find yourself taking on the same or different roles for each group?

- What are the potential strengths of group discussions? What are the potential limitations of group discussions? What are some strategies to enhance a group’s cohesion?

- Reflect back on a time when you were working on a group project in class. Discuss each stage of development (forming, storming, norming, performing, and terminating) as it applied to this group.

- How were/are decisions made in your family? Has the process changed over time? What kinds of communication surround the decision making?

Key Terms

- activity groups

- aggressor

- authoritarian

- authority rule

- blocker

- brainstorming

- climate

- cohesiveness

- collectivist

- common goals

- compromise

- consensus

- democratic

- devil’s advocate

- drive reduction

- encourager

- energizer

- facilitator

- followers

- forming

- gatekeepers

- general norms

- group

- groupthink

- individualistic

- individual roles

- information gatherers

- interaction

- interdependence

- interests/attraction

- joker/clown

- laissez-faire

- leadership

- learning groups

- norming

- norms

- opinion gatherers

- performing

- personal growth groups

- playboy/playgirl

- polarization

- power

- power-from-within

- power-over

- power-with

- primary groups

- problem solving groups

- procedural roles

- promulgation

- recorder

- reinforcement

- role-specific norms

- secondary groups

- self-confessor

- shared norms

- social-emotional roles

- social-emotional leader

- solidification

- storming

- synergy

- task leader

- task roles

- teams

- tension releasers

- terminating

- voting

References

Adams, Susan. “The 10 Skills Employers Most Want In 2015 Graduates.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 12 Nov. 2014. Web.

Bala, Kiran. “Social Media and Changing Communication Patterns” Global Media Journal-Indian Edition 5.1. 2014. Web.

Bass, Bernard M., and Ralph M. Stogdill. Handbook of leadership. Vol. 11. New York: Free Press, 1990.

Baughman, Rachel & Everett-Haynes, La Monica. “Understanding the How-To Of Effective Communication in Small Groups” UANews, 2013. n. pag. Web.

Benson, Jarlath F. Working More Creatively with Groups. 3rd ed. Abingdon, England: Routledge, 2010. Print.

Berkowitz, Leonard. “Sharing leadership in small, decision-making groups.” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 48.2 (1953): 231.

Bowers, John W., et al. The Rhetoric of Agitation and Control. Waveland Press, 2010.

Brilhart, J., and G. Galanes.Group discussion (1998).

Cragan, John, and David W. Wright, and Chris Kasch. Communication in Small Groups: Theory, process, and skills. Cengage Learning, 2008.

Earnheardt, Adam C., Ph.D. “On Becoming a (Pro) Social Med#a Sports Fan.” Spectra 50.3 (2014): 18-22. Print. National Communication Association

Fisher, B. Aubrey. “Decision emergence: Phases in group decision‐making.” Communications Monographs 37.1 (1970): 53-66.

Heider, John. The Tao of Leadership: Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching Adapted for a New Age. 1st ed. Green Dragon, (2005). 178. Print.

Hughes, Richard L., and Steven K. Jones. “Developing and Assessing College Student Teamwork Skills.” New Directions For Institutional Research (2011). Wily Periodicals. Web.

Jensen, Arthur D., and Joseph C. Chilberg. Small group communication: Theory and application. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1991.

Larson, Carl E., and Frank MJ LaFasto. Teamwork: What must go right/what can go wrong. Vol. 10. Sage, 1989.

Lewin, Kurt. Field Research in Social Science. New York: Harper, 1951. Print.

Lumsden, Gay, Donald Lumsden, and Carolyn Wiethoff. Communicating in groups and teams: Sharing leadership. Cengage Learning, 2009.

Maslow, Abraham Harold. Motivation and Personality. 2nd Ed. New York, London: Harper & Row, 1970. Print.

PAC, WIPP, ed. “America Turns the Page: Historic Number of Women in the 113th Congress.” (2013): 1-2. America Turns the Page: Historic Number of Women in the 113th Congress. WIPP/PAC. Web. 7 Dec. 2014.

Paulson, Edward. “Group Communication and Critical Thinking Competence Development Using a Reality-Based Project.” Business Communication Quarterly 74.4 (2011): 399-411.

Richards, Amy, and Jennifer Baumgardner. Manifesta: Young Women, Feminist, and the Future. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000. Print.

Rose, Meleady, Hopthrow, Tim, Crisp, Richard J. “The Group Decision Effect: Integrative Processes and Suggestions for Implementation.” Personality and Social Psychology Review (2012). Sage. Web.

Sherblom, John C. Small Group and Team Communication. Allyn & Bacon, 2002.

Stacks, Don W., and Michael B. Salwen, eds. An integrated approach to communication theory and research. Routledge, 2014.

Starhawk. Truth or Dare: Encounters with Power Authority, and Mystery. San Francisco: Harper, 1987. Print.

Tuckman, Bruce W. “Developmental sequence in small groups.” Psychological bulletin 63.6 (1965): 384.

Wilson, Gerald L., and Michael S. Hanna. Groups in context: Leadership and participation in small groups. McGraw-Hill, 1990.

Last Updated: April 29, 2022

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

WikiBooks: Open books for an open world