2 Perception

Section 1: An Introduction to Social Perception

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- define perception.

- illustrate how patternicity drives perception.

- discuss how self-concept, other-concept, and meta-concept influence communication choice.

- explain how impression management is used to impact meta-concept.

Introduction to Social Perception

In looking at the basics of communication theory, we know humans live in a stimulus-thought-response world. We do not experience the world directly. We sense and then think about external experiences. Our senses are stimulated by things we see, hear, touch, taste, or smell, and then our brains sort through our accumulated store of knowledge to determine what it is. As a result, our perception of what we have seen/heard/touched/tasted/smelled is our interpretation of events. We respond to the interpretation of the events, not to the stimuli directly. Understanding this process of abstraction, of converting reality into thought, aids us in managing communication more effectively.

Perception is a process by which we create mental images of the world around us, the world “out there.” Perceptions determine communication choices, so understanding this process helps us to avoid common perceptual problems. We gain greater insight into how there can be multiple, equally valid perceptions of the same stimuli, increasing our ability to respect a range of diverse views. A significant implication of this understanding is it reveals how much responsibility we receiver-based communicators have in the success or failure of an event. We have to be responsible for those perceptions.

Human beings are natural-born pattern-seekers. In his book, The Believing Brain: From Ghosts and Gods to Politics and Conspiracies, Michael Shermer describes this drive as patternicity. He states, “Our brains are belief engines, evolved pattern-recognition machines that connect the dots and create meaning out of the patterns we think we see in nature” (2011, p. 66). This drive to find patterns is far more than just understanding the world; for primitive peoples, it was a key survival skill. Shermer explains that with such discernment, “we have learned something valuable about the environment from which we can make predictions that aid in survival and reproduction. We are descendants of those who were most successful at finding patterns”(2011, p. 66).

Finding out what something is and having it make sense to us decreases uncertainty. We are driven to learn more and more about the world around us, instinctively looking for cause-effect patterns. The more of these cause-effect patterns we learn, the more we can manipulate and control causes to influence effects. For example, as our knowledge increases of how the human body functions, the better we are at making choices to affect our health. We can choose one food over another one, to exercise or not to exercise, select which medications or dietary supplements to take; all based on understanding the cause-effect patterns of good health. In the field of Communication Studies, the more we understand communication and relational dynamics, the better we become (generally) at managing those relationships. We know actively and genuinely listening to others enhances relationships, so we can learn and apply listening skills to positively affect those relationships. This desire to know drives science and inquiry; it leads us to ask questions about ourselves and our world to increase our sense of confidence in being able to discern “the way things are.”

Understanding perception is crucial for effective communication because we need to accept we cannot truly “experience” another person. We cannot feel what they feel, think what they think, or know what they know. All we can do is take in our sensory observations and draw conclusions about what we think they are like. Remember, humans sense-think-respond, so when we interact we are making communication choices based what is in our head, not directly with the person themselves.

As illustrated in the image, during an interaction between two people, six perceptions are used to make communication choices.

First, our self-concept or how we view ourselves, impacts how we communicate. If Jamal sees himself as interesting and outgoing, he is far more likely to initiate conversations, share personal information, and generally engage other people more easily and comfortably. If Darrin believes he is not very interesting, he is far less likely to engage in such conversations. People who are more optimistic and look for the positives of situations will communicate differently than those who are more pessimistic and look for the negatives of situations. Our communication choices are driven, in part, by how we perceive ourselves.

First, our self-concept or how we view ourselves, impacts how we communicate. If Jamal sees himself as interesting and outgoing, he is far more likely to initiate conversations, share personal information, and generally engage other people more easily and comfortably. If Darrin believes he is not very interesting, he is far less likely to engage in such conversations. People who are more optimistic and look for the positives of situations will communicate differently than those who are more pessimistic and look for the negatives of situations. Our communication choices are driven, in part, by how we perceive ourselves.

Second, we choose how to communicate based on our other-concept, which is our perception of the other person. If Jordan believes Alex is unlikely to understand the jargon she is tempted to use, she will select other, less technical language to get her point across. Dealing with children is an excellent example of how other-concepts guide us: we know we must speak differently to children than to adults, so we adapt our language, communication style, topic selection, and other variables to fit the other person.

Third, we all engage in some degree of impression management; an attempt to influence how others perceive us. Since we cannot read each other’s minds and really know what we think of each other, the most we can do is use our perceptual skills to create an image of how it appears we are perceiving each other. This is our meta-concept. We all have significant people and groups with whom acceptance and belongingness are important, and, as a result, we monitor how those people are responding to us and use those clues to create an image of how we believe they are thinking of us. If Jake is hanging out with a reference group of male friends, and they are laughing at his jokes and responding to his comments, he probably feels good about his meta-concept and will continue to use those same behaviors. On the other hand, if Jake feels ignored and not engaged or valued, he will likely alter what he is doing to get a more favorable response.

Third, we all engage in some degree of impression management; an attempt to influence how others perceive us. Since we cannot read each other’s minds and really know what we think of each other, the most we can do is use our perceptual skills to create an image of how it appears we are perceiving each other. This is our meta-concept. We all have significant people and groups with whom acceptance and belongingness are important, and, as a result, we monitor how those people are responding to us and use those clues to create an image of how we believe they are thinking of us. If Jake is hanging out with a reference group of male friends, and they are laughing at his jokes and responding to his comments, he probably feels good about his meta-concept and will continue to use those same behaviors. On the other hand, if Jake feels ignored and not engaged or valued, he will likely alter what he is doing to get a more favorable response.

Consider a couple going on a date. Each of them may think carefully and plan thoughtfully what they are going to wear, do, and say. Looking for feedback from the other that the date is going well, Taylor may do or say things to elicit a favorable response, and her partner, Chris, will do likewise. They are making communication choices based on how they believe they are being perceived by the other. Taylor and Chris are making choices based on their meta-concepts.

When we decide what to say or how to say it, we make decisions based on our perception of who we think they are, not who they really are. Compare Image 3 to Image 4. In Image 3, when first meeting, Angelina has very little information about Julian; she does not know him yet. As a result, Angelina’s other-concept of Julian (represented by the blue, dashed figure), is heavily based on Angelina’s assumptions about Julian. But as they get to know each other and Angelina observes Julian’s traits, her other-concept moves closer to the reality of Julian’s personality (Image 4). Since it is now based in direct experience, the image becomes a more accurate perception of Julian. As we get to know others, our other-concepts and meta-concepts become more accurate and well-tested. However, no matter how well we know someone, we cannot experience the world directly from their perspective; we can only operate on our own perceptions.

When we decide what to say or how to say it, we make decisions based on our perception of who we think they are, not who they really are. Compare Image 3 to Image 4. In Image 3, when first meeting, Angelina has very little information about Julian; she does not know him yet. As a result, Angelina’s other-concept of Julian (represented by the blue, dashed figure), is heavily based on Angelina’s assumptions about Julian. But as they get to know each other and Angelina observes Julian’s traits, her other-concept moves closer to the reality of Julian’s personality (Image 4). Since it is now based in direct experience, the image becomes a more accurate perception of Julian. As we get to know others, our other-concepts and meta-concepts become more accurate and well-tested. However, no matter how well we know someone, we cannot experience the world directly from their perspective; we can only operate on our own perceptions.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Perception and Communication Choices

- The 6 images in interaction

- How self-concept impacts communication choices

- How other-concept impacts communication choices

- How meta-concept impacts communication choices

References

Section 2: The Perception Process

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- distinguish between the three stages of the perception process: sensory stimulation and selection, organization, and interpretation.

- identify the influences on sensory selection, organization, and interpretation.

The perception process has three stages: sensory stimulation and selection, organization, and interpretation. Although we are rarely conscious of going through these stages distinctly, they nonetheless determine how we develop images of the world around us.

Stage 1: Sensory Stimulation and Selection

Sensory stimulation is self defining: our senses are bombarded by stimuli. We hear, touch, taste, see, or smell something. The neurological receptors associated with these senses are stimulated, and this stimuli races to the brain for processing. However, there is a problem.

We cannot attend to all the stimuli we experience. Given the sheer quantity of sensory stimulation, we cannot pay attention to all of it. We must engage in sensory selection. Sensory selection is the process of determining which stimulus gets our attention and which stimuli we ignore. As with the rest of the perception process, rarely are we aware of this “weeding” process occurring, yet we must manage the sensory load.

An example of sensory selection is the “cocktail party effect.” When we attend a crowded party, with numerous conversations happening at once, we cannot adequately attend to several conversations simultaneously. Instead, we tune out extraneous sounds in favor of the person we wish to attend to. We select the most important stimuli to attend to, and we eliminate the rest (Hamilton, 2013). Another, somewhat unusual example, is clothing. Rarely are we very aware of how our clothes feel touching our bodies, yet there are countless sensory receptors being stimulated. Since the feel of our clothing is not typically very important, we simply ignore it. Yet if we change the situation, such as trying on a new pair of jeans to see if it they fit, we become much more aware of how those clothes feel. In effect, when trying on clothes prior to purchasing them, we are trying to determine if they are comfortable enough so we can weed out the stimuli of wearing them. So “comfortable” means, “I can ignore how they feel.” Wearing formal attire for a wedding, we may notice how odd the suit or the dress feels in comparison to our typical, daily attire. Because the situation has changed, it is more difficult to weed out the stimuli.

An example of sensory selection is the “cocktail party effect.” When we attend a crowded party, with numerous conversations happening at once, we cannot adequately attend to several conversations simultaneously. Instead, we tune out extraneous sounds in favor of the person we wish to attend to. We select the most important stimuli to attend to, and we eliminate the rest (Hamilton, 2013). Another, somewhat unusual example, is clothing. Rarely are we very aware of how our clothes feel touching our bodies, yet there are countless sensory receptors being stimulated. Since the feel of our clothing is not typically very important, we simply ignore it. Yet if we change the situation, such as trying on a new pair of jeans to see if it they fit, we become much more aware of how those clothes feel. In effect, when trying on clothes prior to purchasing them, we are trying to determine if they are comfortable enough so we can weed out the stimuli of wearing them. So “comfortable” means, “I can ignore how they feel.” Wearing formal attire for a wedding, we may notice how odd the suit or the dress feels in comparison to our typical, daily attire. Because the situation has changed, it is more difficult to weed out the stimuli.

As we experience a flood of stimuli, four factors influence what we pay attention to and what we ignore:

1. Needs. We pay far more attention to things which fill a need or requirement. When hungry, we are far more likely to notice places to eat. If we are not hungry, the restaurants, snack bars, and delicatessens are still there, but we do not pay attention to them as they are not meaningful to us at that time. If we need to get somewhere in a hurry, we become very conscious of slower drivers, stoplights, or other such hindrances we might otherwise ignore. All needs have an ebb and flow to it; as need rises, attention rises, but as needs are fulfilled, attention ebbs.

The same dynamic works with people. The need for acceptance may drive us to focus more on signals affirming acceptance or signals indicating a threat to that acceptance. Early in a relationship, partners tend to be highly tuned into each other for this reason; monitoring clues indicating the status of the relationship. If Marcus feels his relationship with Aliyah is uncertain, he will look for clues suggesting trouble or instability. His needs for acceptance and belongingness are being threatened, so his perceptions of relevant stimuli is heightened.

2. Interests. We pay far more attention to those things we enjoy. Scanning channels on television is a good illustration of this process. We click through numerous channels quite rapidly until something catches our interest. We pause on a channel for a moment, and if the interest continues, we quit changing channels; if not, we continue the search. As we speak face-to-face, we tune in and out of conversations as the topics change. A conversation about a football game may not hold our interest, but a conversation about music may pull us in. A young man infatuated with a young woman will be highly attuned to any signal of interest from her, while comments from a casual friend may be ignored.

Interest also allows us to perceive more detail in those things we experience. Intense football fans will see details of play development and strategy casual fans may not recognize. The higher interest in the game leads the fan to learn more, and the more the fan learns, the more the fan can perceive. Devoted NASCAR racing fans see strategy and technique when watching a race; non-fans see a bunch of fast cars turning left. Interest not only drives us to pay attention to the stimuli, it also encourages us to learn more about it, and so we learn to see even more detail and specifics. A dancer who performs with the local Somali traditional music and dance group hears the nuances of the songs and sees the variety of steps in the dances; those new to this type of performance may only perceive people bouncing on the stage.

Interest also allows us to perceive more detail in those things we experience. Intense football fans will see details of play development and strategy casual fans may not recognize. The higher interest in the game leads the fan to learn more, and the more the fan learns, the more the fan can perceive. Devoted NASCAR racing fans see strategy and technique when watching a race; non-fans see a bunch of fast cars turning left. Interest not only drives us to pay attention to the stimuli, it also encourages us to learn more about it, and so we learn to see even more detail and specifics. A dancer who performs with the local Somali traditional music and dance group hears the nuances of the songs and sees the variety of steps in the dances; those new to this type of performance may only perceive people bouncing on the stage.

This cycle applies in all facets of our lives. There are people who can discern every spice in a dish simply by tasting; there are musicians who can identify every instrument in a piece of music just by listening. As our knowledge of effective communication rises, we will be better attuned to the dynamics occurring in a given communication situation, so we will be able to more precisely identify what is or is not working.

3. Expectations. We pay more attention to those things we believe we are supposed to experience. There are two sides to this dynamic. On one hand, if we believe we will experience something, we are more likely to focus on the stimuli fulfilling that expectation and ignore contrary input. Prior to traveling to a new place, if George convinces his best friend Josh, Cleveland is a very dirty city, he will likely “see” a lot of evidence fulfilling that expectation. If Mariana’s friend convinces her a certain college is a real party school, she is more likely to see confirming evidence when visiting the dorms. Years ago, one of your authors had the opportunity to take students from Minnesota to New York City. Prior to the trip, the students talked at length about expecting to see homeless people and prostitutes. As soon as the bus emerged from the Lincoln Tunnel, comments like, “There’s a homeless guy,” or “Is that a hooker?” drifted up and down the bus. They were expecting to see something, and that is what they focused on.

The danger of this dynamic, of course, is allowing expectation to override reality. Since the students expected to see the darker side of New York, they may have been blinded to the diversity and dynamic environment of the bustling city. If a student takes a class from a teacher assumed to be “boring,” the student may not even attempt to engage the material or be active in the classroom.

If we expect to not experience something, we are less likely to “see” it. We do not expect our friends to treat us poorly, so we are less likely to notice behaviors others might consider rude or insensitive. The desire for affection and acceptance can often blind us to such things. A young man may not realize his girlfriend is taking advantage of him because he expects she would not treat him badly, even if his friends are trying to get him to see what is really going on. He does not expect to see evidence of her poor treatment so he, in effect, blinds himself to certain stimuli.

4. Physiological Limitations. Physiological limitations refer to basic sensory limitations; one or more of our senses is limited as to how well it will function. For those who wear glasses, the world is blurred without corrective lenses; what they can sense is very limited by a physical problem. Hearing losses, diminishment of taste and smell, and loss of touch sensitivity can all cause us to have limits on what we can experience.

Many who have extreme physiological limitations often compensate by using other senses in a heightened manner. A man who is blind may attend to sounds at a much higher level than a sighted person, using those sounds as a mechanism for discerning his environment. A woman who is deaf may attend to visual cues at a much higher level than a hearing person for the same reason.

Stage 2: Organization

Once our senses have been stimulated, we move to the second stage of perception, organization. Organization is the process of taking the stimuli and putting it into some pattern we can recognize. As an analogy, when we come home from the grocery story with several bags, we sort those bags into the appropriate cabinets, organizing the items so their placement makes sense for later use.

How we understand this process of organization comes from Gestalt theory. Gestalt is German for “pattern” or “shape,” and the theories address how we translate external stimuli into mental images. Developed in the early 20th century, Gestalt theory states how we process stimuli is a complex process blending external stimuli with internal processes (Rock & Palmer, 1990). In other words, how we perceive the external world is heavily determined by internal influences.

There are four variables affecting how we organize the stimuli we encounter:

1. Patterns. Patterns are pre-existing “templates” we use to order stimuli. These are ways of organizing the stimuli that we have learned and carry with us. As children we are taught basic shapes, like “square,” “triangle,” and “circle,” so when we experience a stimulus fitting those templates, we can make sense of what we see. Parents teach children what it means to be “rude” or “nice,” so we learn to make sense of behavior by using these learned templates.

Consider this image on the left. Most U.S. students will see patterns for each of the top three strings of numbers. The top one fits a standard telephone number for us in the U.S. The next fits the number pattern for a U.S. Social Security number, and the third fits the pattern for a credit card number. The last two, however, may be not be immediately apparent, yet they are commonly recognized patterns in other parts of the world. One is a Costa Rican phone number and a Scottish phone number. Of course, unless we have these templates already in place from our past experiences, we would not discern those patterns. Only because of the templates we have learned will we see these patterns, otherwise they would be just a list of random numbers.

Consider this image on the left. Most U.S. students will see patterns for each of the top three strings of numbers. The top one fits a standard telephone number for us in the U.S. The next fits the number pattern for a U.S. Social Security number, and the third fits the pattern for a credit card number. The last two, however, may be not be immediately apparent, yet they are commonly recognized patterns in other parts of the world. One is a Costa Rican phone number and a Scottish phone number. Of course, unless we have these templates already in place from our past experiences, we would not discern those patterns. Only because of the templates we have learned will we see these patterns, otherwise they would be just a list of random numbers.

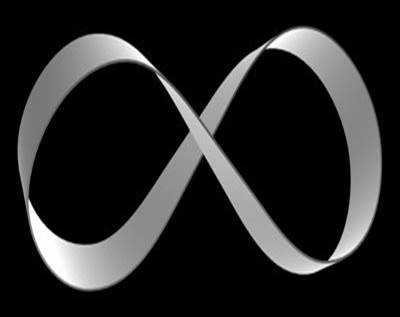

We are always expanding our storehouse of templates. Every time we learn something new, we have created new ways of organizing stimuli. As we learn new words, each word is a new template for that set of sounds or visual shapes. Image 4 is a Mobius Strip. Often used to represent infinity, the ribbon turns so that there is no identifiable inside, outside, up, or down. Once we learn the pattern for “Mobius Strip,” when we see one in the future we are more likely to recognize it. We have learned a new pattern.

We are always expanding our storehouse of templates. Every time we learn something new, we have created new ways of organizing stimuli. As we learn new words, each word is a new template for that set of sounds or visual shapes. Image 4 is a Mobius Strip. Often used to represent infinity, the ribbon turns so that there is no identifiable inside, outside, up, or down. Once we learn the pattern for “Mobius Strip,” when we see one in the future we are more likely to recognize it. We have learned a new pattern.

As discussed with sensory stimulation, the more of an interest we have in something, the more we learn about it, so that means we learn more and more patterns for that subject. Thus, when we experience something in an area of interest, we can discern more detail as we have more patterns to apply.

2. Proximity. Proximity refers to how we see one object in relation to what is around it. We do not just see a person; we see the person within their surroundings which affects our interpretation of that person. A specific dynamic of proximity is the figure-ground relationship. The figure-ground relationship posits that as our focus on the object (the figure) and the background (the surroundings) change, interpretation changes.

2. Proximity. Proximity refers to how we see one object in relation to what is around it. We do not just see a person; we see the person within their surroundings which affects our interpretation of that person. A specific dynamic of proximity is the figure-ground relationship. The figure-ground relationship posits that as our focus on the object (the figure) and the background (the surroundings) change, interpretation changes.

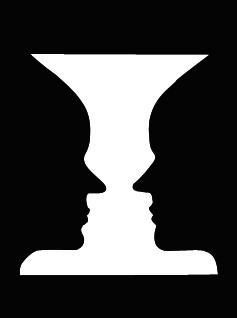

In the classic faces/vase image (Image 5), whether we focus on the background or the figure alters our interpretation. By focusing on the black background, most see the outlines of two faces in profile; by focusing on the white figure, most see a vase. When we shift our focus between the figure and background, our perception changes.

In applying the concept of figure-ground to people, consider professors. Seeing a professor on campus is unremarkable; we think little of it. If, however, we see them late at night coming out of a bar with a questionable reputation, our perception may be altered based on seeing them in that background. Politicians are very aware of this dynamic, avoiding backgrounds that may cause problems. A politician does not want to be seen in a strip club but does want to be seen in church. When the President visits Minnesota, politicians of that party may scramble to be seen with him, while politicians of the opposing party may make a point of staying away. Seeing a young adult with a backpack on the Ridgewater College campus would undoubtedly be interpreted as “student.” Seeing that same person with a backpack at a shopping mall, however, does not automatically lead to the same conclusion due to the differences in proximity.

Another aspect of proximity is grouping. We tend to assign similar traits and characteristics to items that are grouped together. Looking at the groups in the three images above, most will assume each person in the group shares traits with the others in the group. They look similar and they are physically close to each other. We assume these similarities even though we know nothing about the personality traits of the individuals

3. Simplicity. As we now know, we are driven to lower uncertainty and make sense of the world around us. In lowering uncertainty, we tend to favor the easiest, least confusing perception of a person or event; we like simple perceptions. First impressions are so powerful because once we have created an initial perception, it is far simpler to keep it than change it. It is hard for us to change our perceptions because changing our minds causes complexity, and the drive for simplicity is a powerful, countering force.

While a normal process, this drive for simplicity can be dangerous. We can be guilty of oversimplifying complex issues. An anthem of the Sixties was “All You Need is Love,” a 1967 Beatles song written by John Lennon specifically for the first live, global television broadcast (Harrington, 2002). While such sentiments are admirable, the issues facing the world are far more complex. We still see the same drive to take very complex issues and narrow them down to simple solutions. Effective problem solving means identifying the underlying causes, effects, and consequences of a given issue. If we do not acknowledge and work with that complexity, we risk dramatic failures. For example, the U.S. has made efforts to bring democracy to countries dominated by conservative religious groups, such as the Taliban in Afghanistan. Some simplistically assume that since secular democracy works here in the U.S., it will work everywhere. However, in the U.S. we are very comfortable with the separation of church and state, but in some countries, the two are so intertwined they cannot be separated; the church is the state. United States’ efforts to create a secular government fail as the complexities of that culture are not adequately considered. Part of understanding the complexities involved lies in recognizing that culture is visible (clothes, skin color, food) and invisible (values, beliefs, attitudes), both of which are expressed through behavior. Communicating effectively with complex cultures and individuals requires us to accept complexity and to resist over-simplifying.

This drive to simplicity affects how we perceive individuals. The power of stereotyping is simplicity. Stereotypes are generalizations about a group of people categorized by an external marker, like sex, and skin color. Having one way of looking at an entire group is much simpler than treating each member of that group as an individual with a unique personality. It is far simpler to assume that “all blonds are dumb” or “all students are lazy” than to let each individual blond or each individual student emerge as a unique person. Individual perception takes time and effort; group stereotyping is easy. Stereotyping is a simplistic way of perceiving the world around us.

We can see this simplicity at work in popular culture with something called type-casting. In selecting actors for a TV show or movie, it is common that stereotypes come into play. Actors are often cast on their ability to reflect stereotypical representations of different character types. According to Reactions to Counterstereotypic Behavior: The Role of Backlash in Cultural Stereotype Maintenance,

Stereotypes organize information, aid in decision-making, provide norms, and support legitimizing ideologies, among other purposes. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine literature, film, opera, and television sitcoms without their heavy reliance on stereotypes…. The resulting picture is one of a social enterprise in which observers and actors alike conspire to maintain stereotypes by policing others and themselves in order to preserve the social order. The consequences are clearly unfavorable for atypical actors and, ultimately, for a society that constrains people to behave within the limits of stereotypic beliefs (Rudman & Fairchild, 2004).

In other words, the use of stereotypes as guidelines for how characters are to be portrayed is seen as more favorable than portraying a character in non-stereotypical ways. We see portrayals of Arabs as either oil billionaires or terrorists; or in the news about a natural disaster in Mexico, the locals are shown as patient and passive, and in need of help from America. African American women used to be portrayed as domestics but now are more likely to be seen in the background as a homeless person, a prostitute, or an angry black woman. Asian Americans are shown as academically gifted or as without friends, and not much else. Caucasions do not escape the broad brush of stereotypes in the media; they may be likewise type cast as the clueless father, the dizzy, frantic mother, or the spoiled child. As these stereotypes fill our televisions and stream to our electronic devices, they reinforce the existence of the stereotype in a powerful cycle.

4. Closure. Closure is the psychological drive for completeness. Again, with our powerful need to lower uncertainty, it is much more comfortable to perceive a whole, complete picture than partial images that do not seem to make sense. As a result, we will fill in missing stimuli to make the incomplete appear whole.

4. Closure. Closure is the psychological drive for completeness. Again, with our powerful need to lower uncertainty, it is much more comfortable to perceive a whole, complete picture than partial images that do not seem to make sense. As a result, we will fill in missing stimuli to make the incomplete appear whole.

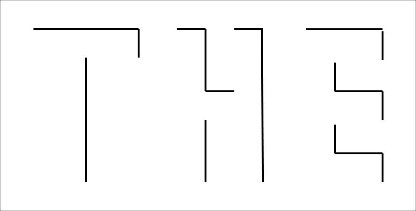

While Image 9 may look like the word THE, note that the letters T, H, and E are not fully present. Instead, due to the proximity of the lines to each other, it is simpler to imagine the missing lines to see a whole word than leaving it as a collection of unrelated lines. In fact, in years of using this example, native English-speaking students always see the word THE. In applying this to people, if a friend does or says something unusual, we will create an explanation that at least temporarily explains what happened. It may not be correct, but being right is not as important as lowering uncertainty. For example, Ashley, whom we think is very open-minded, tells a racist joke. This creates uncertainty in us as it is so out-of-character for Ashley. We will try to determine why she did such a thing, trying to make sense of the inconsistent behavior. We may think, “She didn’t realize how racist that is,” or “She’s being sarcastic.” Until we can ask Ashley directly, we rely on these assumptions to explain the inconsistency and lower the uncertainty.

Engaging in closure, while perfectly natural, also can be dangerous. For some, once they fill in the missing information, they will take it as fact, not supposition. Their assumption becomes a false reality. The number of interpersonal conflicts caused by what we assume about the other is staggering.

Consider the image on the right, what might most assume about this person? Although we know virtually nothing about her, other than what we see in front of us, we immediately have a list of assumptions about this person. And in today’s digital world, we cannot even be confident the image is real, as the photograph may be heavily manipulated.

When we use closure, we assume our internal beliefs are true about external stimuli, and the probability of error is very high. While closure can give us temporary satisfaction, we need to be receiver-based and realize our assumptions can be wrong and must be tested for accuracy. As the reality of the situation emerges, we then alter our perception of the event.

Stage 3: Interpretation

After sensing the stimuli and organizing it into something recognizable, we attach a label; we interpret it. The interpretation stage is where we make sense of what we have experienced; we determine what it means to us. From the communication model, we know how we interpret input is determined by our field of experience; we learn how to see the world. There are a number of processes impacting how we interpret the stimuli.

1. Implicit Personality Theories: In 1954, psychologists introduced the concept of implicit personality theories, suggesting that we do not learn a person’s traits one at a time; rather, we see them in “groups” (Schneider, 2004, p. 173).

Social Psychologist Solomon Asch found that the presence of one trait led people to assume the presence of other traits (McLeod, 2008). When we see one trait, such as gender, we make all sorts of assumptions as what the person is like; we assume the presence of trait A implies the presence of traits B, C, D, and so on. Two types of implicit personality theories are the halo effect and stereotyping.

The halo effect is our belief that traits tend to cluster, that traits “naturally” appear in groups. We tend to assume certain traits just normally go together; once we experience one trait, we assume other traits just fall into place: “It is the idea that global evaluations about a person (e.g. she is likeable) bleed over into judgments about their specific traits (e.g. she is intelligent)” (Psyblog, 2007). This is most noticeable with attractiveness. As Asch discovered, we tend to assume those we see as “attractive” have multiple, positive traits, whether we have directly experienced them or not, and for those we find unattractive, we tend to assume multiple, negative traits. Obviously, our perceptions could be very far off in such a process. Remember the influence of expectations on sensory selection; we are more likely to see what we expect to see. Considering the influence of simplicity, it is far simpler to cluster traits than to allow for a rich diversity of personality types. As a result of these perceptual influences, this tendency to cluster traits is quite strong and can be challenging to counter.

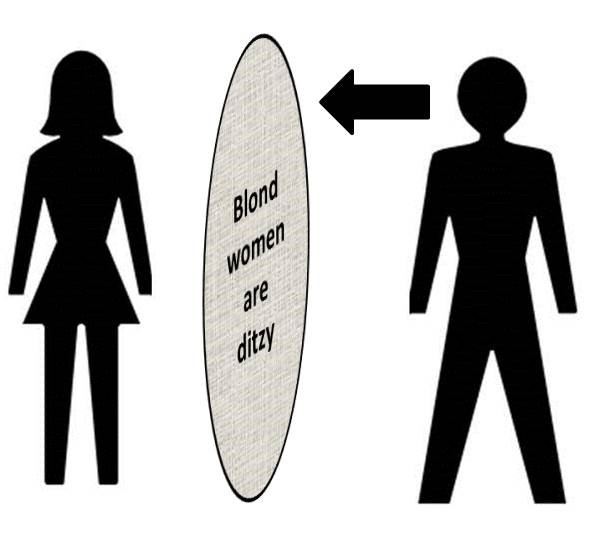

Stereotyping is a more extreme type of implicit personality theory. While the halo effect links traits to each other, stereotyping links traits to people. Stereotyping is the association of traits with a group of people usually categorized by an external marker. We group people most often by some trait we can observe, such as gender, race, skin color, weight, height, or hair color, and then, we assume what we think is true of that group is true of each individual. If Doug believes the stereotype, “All blond females are dumb,” he is using two external markers, “blond,” and “female.” When he sees a blond female, he assumes she is dumb regardless of what she is really like. Doug sees two traits, and then he assumes other traits based on those external markers. Our assumptions dictate what a person is like rather than drawing our image of them from actual experience. As illustrated in image 11, stereotypes place themselves between us and the other person, severely distorting our perception of the other.

Stereotyping is a more extreme type of implicit personality theory. While the halo effect links traits to each other, stereotyping links traits to people. Stereotyping is the association of traits with a group of people usually categorized by an external marker. We group people most often by some trait we can observe, such as gender, race, skin color, weight, height, or hair color, and then, we assume what we think is true of that group is true of each individual. If Doug believes the stereotype, “All blond females are dumb,” he is using two external markers, “blond,” and “female.” When he sees a blond female, he assumes she is dumb regardless of what she is really like. Doug sees two traits, and then he assumes other traits based on those external markers. Our assumptions dictate what a person is like rather than drawing our image of them from actual experience. As illustrated in image 11, stereotypes place themselves between us and the other person, severely distorting our perception of the other.

The danger with stereotyping is believing and acting as if our stereotype is true, regardless of actual, direct experience. A frequent complaint of people of color is being treated with suspicion in stores. “Shopping While Black” refers to experiencing discriminatory behaviors while shopping, such as being followed, not being helped, or being erroneously accused of shoplifting (Williams, Henderson, & Harris, 2001).

2. Assumed Similarity/Assumed Dissimilarity. When first meeting people, we make a very quick assessment of how similar or different we are. We see similarities or differences in gender, age, body size, demeanor, dress and other such superficial features. If Megan’s initial assessment is that she is similar to Lindsey, she will assume they share many traits beyond these; Megan assumes similarity. If her initial assessment is they are different, Megan will assume what is true of her is not true of the other; she assumes dissimilarity. It is important to emphasize that these are still our internal assumptions based on very limited information, and that we may very well be wrong in our perceptions.

Assumed similarity/dissimilarity is quite noticeable in attraction. Juan sees a girl, Magdalena, to whom he is quite attracted. In an effort to connect with her, Juan will focus on what he and Magdalena have in common, even if it means ignoring obvious differences. Juan assumes similarity with Magdalena in order to encourage the relationship. On the other hand, if Magdalena finds Juan annoying, she will emphasize dissimilarity to discourage the relationship, even if it means ignoring obvious similarities.

3. Self-fulfilling Prophecies. A self-fulfilling prophecy has three stages: prediction, action, and verification. We predict something. We then act, often unconsciously, in a manner that makes it come true. Once it comes true, we have then verified our prediction. If Sterling says to himself, “I can’t pass the test,” he is less likely to study. This inadequate preparation leads Sterling to fail, thus verifying the initial prediction. If Lee decides to go with his girlfriend to see what he thinks is a “chick flick,” he may very well go into the theatre with the assumption, “This movie will be stupid, and I will not enjoy it.” Lee will then tend to focus on anything he sees as “stupid,” reinforcing his initial assumption. Because he focused on parts of the movie fulfilling his prediction, Lee ends up experiencing a “stupid” movie in his mind. If a student has a firmly held expectation about an instructor being boring, they are more likely to look for evidence the teacher is boring instead of allowing their perception of the instructor to be based on what the teacher actually does in the classroom. Self-fulfilling prophecies distort perceptions by distorting our focus.

4. Perceptual Defense. Perceptual defense is our drive to maintain existing or strongly desired interpretations. The power of simplicity tells us that changing interpretations can be very discomforting. We do not like to change how we look at something, especially when the required change is from a comfortable, less troubling interpretation to a more troubling one. The first step for a person to seek help for alcoholism is to change their self-perception from “I don’t have a problem” to “I do have a problem.” This is a very difficult and disconcerting perceptual shift, and accordingly it is a challenging first step in seeking help.

Our tendency to look for evidence supporting what we want to be true is confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is our tendency to emphasize and attend to evidence that supports conclusions we favor, and conversely our tendency to minimize and ignore evidence that is contrary to our desired perceptions (RationalWiki, 2013). If Aila does not want to accept that her son, Rashid, is a bully and trouble-maker at school, she will reject, minimize, or dismiss any evidence the school presents her supporting that view. Since it is more comfortable to maintain the perception that Rashid is a good student, she defends her perception by discounting the evidence that questions her viewpoint. Parents do not like to see their children having trouble socially or physically, but if they do not shift their perception and acknowledge reality, they will not be driven to seek help for their child. As our parents age, we do not wish to see them beginning to fail physically or mentally. We do not like to see our loved ones moving toward death, yet if we do not acknowledge those changes, we cannot take measures to aid our parents in their advanced years.

With the advent of the internet, we have seen a dramatic growth in the tendency of people to exist in an echo chamber to fulfill their confirmation biases (DiFonzo, 2011). An echo chamber is a virtual space in which we receive only information which confirms positions and beliefs we prefer. In the 2012 election, many Republicans were taken aback by the loss of Mitt Romney to Barack Obama. After the election, some suggested the reason they were surprised is they were getting all of their news and information from conservative information sources, like Fox News, World News Daily, and other heavily biased sources. To maintain audience ratings, these sources would only report information the audience wanted to hear, information that confirmed their bias. When the election results came in, many were simply not aware of the support for Obama as their sources had not reported that information, or at least had done so in a distorted way. Limiting oneself to an echo chamber can happen with any group anywhere on a value spectrum, and the internet has made living in such echo chambers extremely easy.

5. Social pressure. Acceptance and belongingness are fundamental human drives. One way to meet these needs is to share perceptions. In the 1950s, Solomon Asch found that in many instances, we will conform to perceptions different than our own, at least temporarily, to avoid threats to our sense of acceptance (McLeod, 2008). We will tend to laugh along with others, even if we are not exactly sure what is funny. As we talk to our friends, we naturally share how we see the world, they share how they see the world, and we tend to adapt to each other. A reference group of five high school guys will have very similar interpretations of what it means to be “cool,” what it means for a girl to be attractive, and what movies or music are good. Of course, this holds true for female groups or mixed gender groups as well. When confronted with the choice of having a different perception and risking acceptance, or having a similar perception and enhancing acceptance, we often gravitate to the shared perception.

Actions based on this drive for acceptance is commonly called herd mentality. Dr. Conlin Torney of the University of Exeter explains:

Social influence is a powerful force in nature and society. Copying what other individuals do can be useful in many situations, such as what kind of phone to buy, or for animals, which way to move or whether a situation is dangerous. However, the challenge is in evaluating personal beliefs when they contradict what others are doing. We showed that evolution will lead individuals to overuse social information, and copy others too much [sic] than they should. The result is that groups evolve to be unresponsive to changes in their environment and spend too much time copying one another, and not making their own decisions (University of Exeter, 2014).

As with other perceptual processes, the danger with social pressure and a herd mentality is not realizing how our personal beliefs, values, and behaviors may be compromised. We may act in ways that, upon reflection, are inconsistent with long-held beliefs. For example, a common issue for new college students is balancing finding a place of acceptance and inclusion on campus without giving in to social pressures to act in uncomfortable ways such as drinking alcohol. Sometimes the conflict of social pressures to drink and one’s personal belief in moderation becomes quite strong and can lead to some compromising decisions.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Sensory Stimulation and Selection

References

Section 3: Perception of self

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- define self-perception and how it is comprised of self-concept and self-esteem.

- explain how self-image is comprised of self-appraisal and feedback.

- explain how self-esteem is the developed via the application of a criterion.

- differentiate between internal standards and external standards in the development of self-esteem.

- describe how the fallacy of oughts and musterbation impact self-esteem

Self-Perception

How we perceive others has a direct impact on how we choose to communicate with them. Recalling the six images conceptSelf-concept, other-concept, and meta-concept. Module II, Section 1, the first image that comes into play is actually our perception of self. Our self-perception influences how we choose to present ourselves to those around us. If Bev sees herself as confident and interesting, she is more likely to be outgoing and talkative. If Ruth sees herself as uninteresting, she is more likely to be shy and more hesitant to engage others.

Self-Perception is an image we hold about our self and our traits and the judgements we make about those traits. Self-perception includes two, core perceptual processes: our self-concept, or the picture we have in our heads of who we are; and our self-esteem, or how we judge and evaluate those traits.

A note of caution before we continue. Self-concept and self-esteem are complex, psychological dynamics with a myriad of influences. The intention here is introduce a basic, perception-based way to view self-concept and self-esteem. In other words, this is a simplified look at a complex human dynamic. Realize that to understand this topic, there is far more to learn from fields such as psychology and sociology.

Self-Concept

Our self-concept is our perception of the traits we have, a list of the characteristics we see in ourselves. This list is not positive nor negative, but it is just a list of what we believe is true about ourselves. We create our list through self-appraisal and feedback from others. Our self-appraisal is our perception of our traits and behaviors.  It is like looking in a mirror and using our own senses to perceive what we are. We must realize, however, that the perceptual processes that influence our interpretation of others applies to us as well. Those influences can lead to a distorted picture. As teenagers, we all went through the acne stage, and at times we became overly focused on a single spot to the point that it was all we could see in the mirror, when others may have barely noticed it. A young man distraught about his family’s history of male-patterned baldness may be hyper-attuned to his hair and any changes, over emphasizing slight variations in thickness. On a more serious note, an individual with anorexia nervosa will perceive herself as “fat” when, in fact, she may be dangerously underweight. As we know about the perception process, we cannot always believe our own eyes, so we need to be kind to ourselves, realizing our perceptions can easily be distorted.

It is like looking in a mirror and using our own senses to perceive what we are. We must realize, however, that the perceptual processes that influence our interpretation of others applies to us as well. Those influences can lead to a distorted picture. As teenagers, we all went through the acne stage, and at times we became overly focused on a single spot to the point that it was all we could see in the mirror, when others may have barely noticed it. A young man distraught about his family’s history of male-patterned baldness may be hyper-attuned to his hair and any changes, over emphasizing slight variations in thickness. On a more serious note, an individual with anorexia nervosa will perceive herself as “fat” when, in fact, she may be dangerously underweight. As we know about the perception process, we cannot always believe our own eyes, so we need to be kind to ourselves, realizing our perceptions can easily be distorted.

The feedback we get from others is a way we can check and validate our self-appraisal. If Todd sees himself as a very funny person, people laughing at his jokes would validate his self-appraisal. He would see evidence that he is viewed by others the same way he views himself. If Marjorie sees herself as a caring friend, having others seek her out for comfort and support validates that self-appraisal. Marjorie sees evidence that others see her as a caring person.

Sometimes we may see an incongruity between our self-appraisal and feedback from others. For instance, Don may think he is an interesting conversationalist, yet no one seems to want to carry on a conversation with him. When faced with this sort of disparity, Don can either reevaluate his self-appraisal, or he can choose to ignore the feedback. The origin of the feedback makes a difference. Feedback from our reference groups will usually be harder to ignore, while feedback from strangers can be more easily dismissed. While ignoring feedback from trusted individuals may be risky, being overly sensitive to the reactions of others is likewise unhealthy. In our western culture, we tend to emphasize traits we see as negative, so reevaluating our self-appraisal in light of this feedback can be a healthy way to keep our self-image in check.

Self-Esteem

After we become aware of our traits, we evaluate them; we judge whether we like a specific trait or behavior. For instance, Gabrielle may evaluate her weight as undesirable; thus, her self-esteem in this aspect of her self-concept is lower. However, she may also evaluate her relationship with her partner as a very good and healthy, so she has higher self-esteem in this aspect of her self-concept.

In order to evaluate anything, including our traits and behaviors, we must compare those traits and behaviors to something. We use criteria, standards by which we measure something. If we are interested in buying a certain car, the only way we can evaluate the price is by comparing it to other cars of similar value. We may shop around at various dealers, or perhaps we look up the suggested retail price from Kelley’s Blue Book. That suggested price is a criterion, a measure, by which we can determine if the offered price is appropriate.

Our self-esteem works the same way. Our fields of experience contain standards by which we measure and judge ourselves. For Esther to evaluate her weight, she can compare herself to those in her reference group, to her relatives, to medical height/weight charts, to celebrities, and so on. As the criteria, the thing to which she compares herself, changes, her evaluation will likely change. If weight issues run in her family, in comparison to them she may see her current weight favorably. If she compares her weight to what the medical community deems appropriate for her height, however, that evaluation may be less positive. We all have ideas of what it means for a person to be attractive, and we use those as standards to judge ourselves as well. So if Esther’s sense of attractive body size is the unrealistically thin nature of many models and celebrities, she may judge her weight quite severely.

Self-esteem, then, is a function of the perceived distance between our criteria and our current selves. As we move closer and closer to our goals, our self-esteem strengthens. Too often we assume the only way to improve self-esteem is to change the reality of ourselves, such as losing weight, to be closer to our ideal. However, another avenue is to re-evaluate and re-consider the criteria itself. Often, the standards we hold for ourselves are unrealistic and unattainable. The type of standard we use to evaluate ourselves is crucial in maintaining healthy self-esteem. There are two sources for these criteria: internal standards, and external standards.

Internal standards are standards we have decided are right and reasonable for us individually. We use these to set goals and direction in our lives. If Khalid has decided that earning a college degree is right for him, that standard helps him have a clear goal; it can give a sense of direction and purpose. Khalid can evaluate his behavior based on how well it aids him in reaching his goal. If Juliana decides that losing 20 pounds is a proper goal for her, she has a concrete, measurable target. She can measure herself by her progress in reaching that goal. These are goals to reach, and they are realistic and attainable.

Internal standards are standards we have decided are right and reasonable for us individually. We use these to set goals and direction in our lives. If Khalid has decided that earning a college degree is right for him, that standard helps him have a clear goal; it can give a sense of direction and purpose. Khalid can evaluate his behavior based on how well it aids him in reaching his goal. If Juliana decides that losing 20 pounds is a proper goal for her, she has a concrete, measurable target. She can measure herself by her progress in reaching that goal. These are goals to reach, and they are realistic and attainable.

External standards, however, can be dangerous. When we fall prey to standards that are thrust upon us by societal forces, such as family, friends, and media, we are in dangerous territory. Consider the unrealistic standards our entertainment industry sets for physical appearance for both males and females. We see highly manipulated images of attractiveness, and through constant exposure to those images we can begin to feel they embody the criteria we need to reach. The Dove Campaign for Real Beauty (Dove 2013) is an example of an attempt to counter these overwhelming external pressures, and to emphasize the need to measure oneself internally, not on what others say we should be. Focused on young women, the program works to make people aware of those external pressures and, as a result, to reduce the influence of such societal images.

These external, social pressures are very powerful, and they are not accidental. In The Poverty of Affluence, Paul Wachtel (1988) argued that advertising deliberately works at keeping those standards just out of reach. Advertising creates ever-moving standards of beauty, wealth, health, or other such measures. By constantly changing the standards, we keep buying their products to try to meet those false standards. We can always be thinner, have more/better hair, look sexier, or act cooler. Continually setting new standards for dress and appearance drive purchasing.

Wachtel goes on to explain that this constant inadequacy leads to us to measure ourselves in terms of material possessions or money. If we do not have the right type of car, house, clothing, hair style, and on and on, we are not “with it.” The way to be “with it” is to buy something that someone else says we ought to have, wear, or use. This is such a danger to our self-esteem because as one matures, the search for higher self-esteem can lead us into a more and more frantic attempt to meet these unrealistic standards.

In this frantic attempt, we easily fall prey to the fallacy of oughts. The fallacy of oughts is the mistaken belief that we must satisfy everything we ought to be, ought to do, ought to buy. These oughts are the products of our society, our peers, our colleagues and advertising. These are the standards we mistakenly feel we must live up to. Once we get caught in the trap, we start what Albert Ellis labelled musterbating, the act of attempting to meet this powerful and overwhelming world of oughts (Nemade, Staats Reiss, & Dombeck, 2007). We constantly strive to fulfill the external standard, ignoring our internal standards.

Although the external pressures to measure up to social standards can be very powerful, as we become aware of those influences, we can combat them. We can use our internal standards to evaluate the external ones, assimilating those we find appropriate for us, but tossing aside those that are not. However, if we are under the influence the external standards, our internal ones often fall by the wayside, buried in the onslaught of external forces.

Perception of self is the same process as perception of others, just turned on oneself. We sense information about ourselves, either through self-appraisal or from the feedback from others. We use this information to create our self-image, a list of our traits and characteristics. And we interpret what that self-image means to us; we measure how much we like those traits, developing our self-esteem.

As mentioned at the beginning of this section on self-concept, self-esteem issues can be quite complex, influenced by a multitude of factors in one’s life. To learn more about self-concept issues, consider an appropriate psychology class to investigate the deeper dynamics of self-concept.

We see that perception of self is subject to the pressures of variables that can cause distortions in that perception. By recognizing those pressures, we can moderate the effects of those pressures.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

References

2101 15th Ave NW

Willmar, MN 56201

(320) 222-5200

Keith Green, Ruth Fairchild, Bev Knudsen, Darcy Lease-Gubrud

Last Updated: June 17, 2019

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.