10 Intercultural Communication

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- describe what it means to be a provisional communicator.

- define culture and co-culture.

- explain how culture may impact communication choices.

- apply Hofstede’s dimensions of culture to oneself and a group.

- show how Hall’s cultural variations apply to oneself and a group.

- identify barriers to intercultural competence.

Humans are naturally egocentric. Since we can exist only within our own heads, it is perfectly natural for us to assume everyone else thinks, perceives, and communicates as we do. The only world we can experience is the world as we see it, and it can be very challenging to understand that varied perceptions, values, and beliefs exist which are equally valid.

Being a provisional communicator can be challenging. Provisionalism is the ability to accept the diversity of perceptions and beliefs, and to operate in a manner sensitive to that diversity. Being provisional does not mean we abandon our own beliefs and values, nor does it mean we have to accept all beliefs and values as correct. Instead, provisionalism leads us to seek to understand variations in human behaviors, and to understand the field of experienceSee Module I, Section 2 for a discussion of field of experience. out of which the other person operates. This adds an extra step to the interpretation process:

- We interpret the world within our own life experiences, but then

- We stop and consider, “How was the message intended?” or “What other factors may be motivating this behavior?”

For example, in the dominant U.S. culture, we are taught it is rude to stare at people, especially those markedly different from ourselves. We consider such extended gazes unsettling, and we question why the person is doing it. This is not true, however, in all cultures. When Keith was in China several years ago (Image 1), he had

For example, in the dominant U.S. culture, we are taught it is rude to stare at people, especially those markedly different from ourselves. We consider such extended gazes unsettling, and we question why the person is doing it. This is not true, however, in all cultures. When Keith was in China several years ago (Image 1), he had

to acclimate to this cultural difference. Since he stood out as markedly different; lighter skinned, bald, taller, and larger than the average Chinese, he would regularly catch people staring at him, and many were doing so quite openly and obviously. If he had simply used an egocentric interpretation, interpreting them according to his own culture, he would have drawn the conclusion they were very rude. Since Keith knew from various travel books of this cultural difference, he was able to be provisional and understand their behavior was perfectly appropriate within the context of their culture. If he had not learned about the culture, he might have experienced even greater culture shock. This term refers to the discomfort felt when interacting in a new environment with few familiar cues to guide our communication behaviors (Martin & Nakayama, 2018).

In addition to cultural differences, we also experience variations in communication behaviors between men and women. For example, Keith’s wife and her sister can talk for hours about all sorts of relational issues with co-workers, with family members, and with friends while he finds such extensive conversations exhausting. Since female communication is far more focused on relationship development and maintenance, such conversations are consistent with the feminine communication style. The masculine style is far more focused on action and the bare details of events, who did what to whom, and not as focused on the nuances of relational dynamics. As someone who uses the masculine style, once Keith gets the basic details, he thinks he is informed and does not feel a need to dissect the smaller details of the event. Note that the masculine and feminine communication styles are not based on biology; men can use a feminine style and women can use a masculine style. In Module III, Section 2 See Module III, Section 2 , you will learn more about these styles and how we move between them depending on the situation.

Culture and gender impact communication. As with all human behavior, when we address such variations, we always speak of tendencies, not absolutes: men tend to communicate one way, and women tend to communicate somewhat differently. Imagine if a visitor from another culture was to ask you, “What are Americans like?” Chances are you could identify a few characteristics but would also qualify your statements with, “But not everyone….”

Each of us exists within a dominant culture and is a member of several co-cultures. Our culture is the broad set of shared beliefs and values that form a collective vision of ourselves and others. Culture is learned, and it can be so ingrained it becomes challenge to identify how it influences our thoughts and behaviors. For example, in U.S. culture, we place a high value on self-determination: we have a fundamental right to make choices we deem best for us. As long as our actions do not harm others or inhibit their choices, we feel free to follow the life path of our choosing. If others attempt to force us to act or think in certain ways, we tend to rebel. Other cultures are more collectivist, and the emphasis is placed on doing what is best for the group. In such cultures, engaging in individual behaviors that reflect poorly on the group is a powerful social taboo. For example, in some Asian cultures if a student performs poorly academically, it is seen as a reflection on the entire family, bringing shame to all. The pressures to succeed are based not on personal achievement but on maintaining the honor of the entire family. Contrast that to dominant U.S. culture in which students are generally seen as failing, or succeeding, on their own merit.

Each of us exists within a dominant culture and is a member of several co-cultures. Our culture is the broad set of shared beliefs and values that form a collective vision of ourselves and others. Culture is learned, and it can be so ingrained it becomes challenge to identify how it influences our thoughts and behaviors. For example, in U.S. culture, we place a high value on self-determination: we have a fundamental right to make choices we deem best for us. As long as our actions do not harm others or inhibit their choices, we feel free to follow the life path of our choosing. If others attempt to force us to act or think in certain ways, we tend to rebel. Other cultures are more collectivist, and the emphasis is placed on doing what is best for the group. In such cultures, engaging in individual behaviors that reflect poorly on the group is a powerful social taboo. For example, in some Asian cultures if a student performs poorly academically, it is seen as a reflection on the entire family, bringing shame to all. The pressures to succeed are based not on personal achievement but on maintaining the honor of the entire family. Contrast that to dominant U.S. culture in which students are generally seen as failing, or succeeding, on their own merit.

Cultures do not have static sets of beliefs and values; instead they will evolve over time. In the U.S. we have seen large cultural shifts in the past 50 years. Sexual mores have changed quite dramatically, as have our attitudes about individual rights. While in the past women were restricted to a narrow range of careers, today we assume men and women are equally able to pursue the career of their choice. We continue to evolve attitudes toward minorities and immigrants. During the past 10 years, the changes in attitudes toward homosexuality and the civil rights of same-sex couples are quite striking.

It is also important to note a broad culture, like the U.S., will also have a number of cultural groups within it, sometimes called co-cultures. This refers to an identifiable group with their own unique traits operating within the larger culture, such as Native Americans, African Americans, Latinos, and similar groups with their own distinct cultures. In addition to culture and co-culture, others terms are used to refer to this aspect of cultures, such as majority and minority cultures or dominant and nondominant cultures or macro- and micro-cultures. These terms attempt to reflect the importance of culture in the broader sense and the reality of the greater power that some cultures have within a society. Some groups within a larger culture relate to the social identities of those involved. These may be based on regions (the old South, the East Coast, urban, rural), religion or beliefs: (Catholics, Southern Baptists, Lutherans, Buddhists, Muslims, atheists), or affiliation (street gangs, NASCAR fans, college students). Such groups are not cultures per se but groups of people who share concerns and who might perceive similarities due to common interests or characteristics (Lustig & Koester, 2010).

It is also important to note a broad culture, like the U.S., will also have a number of cultural groups within it, sometimes called co-cultures. This refers to an identifiable group with their own unique traits operating within the larger culture, such as Native Americans, African Americans, Latinos, and similar groups with their own distinct cultures. In addition to culture and co-culture, others terms are used to refer to this aspect of cultures, such as majority and minority cultures or dominant and nondominant cultures or macro- and micro-cultures. These terms attempt to reflect the importance of culture in the broader sense and the reality of the greater power that some cultures have within a society. Some groups within a larger culture relate to the social identities of those involved. These may be based on regions (the old South, the East Coast, urban, rural), religion or beliefs: (Catholics, Southern Baptists, Lutherans, Buddhists, Muslims, atheists), or affiliation (street gangs, NASCAR fans, college students). Such groups are not cultures per se but groups of people who share concerns and who might perceive similarities due to common interests or characteristics (Lustig & Koester, 2010).

Within each of the social groups, communication is influenced. Consider:

- The use of specific gestures, colors, and styles of dress in inner city gangs;

- The classic Southern Accent;

- The use of regional sayings, such as “you betcha,” or “whatever” in rural Minnesota;

- The more quiet nature of Native Americans who may prefer to listen and observe.

These cultural groups and social identities operate within the larger culture while maintaining the traits that make these smaller groups unique. These variations in lifestyle, communication behaviors, values, beliefs, art, food, and such provide a rich quilt of human experience, and for the provisional communicator, one who can accept and appreciate these difference, it can be an invigorating experience to move among them.

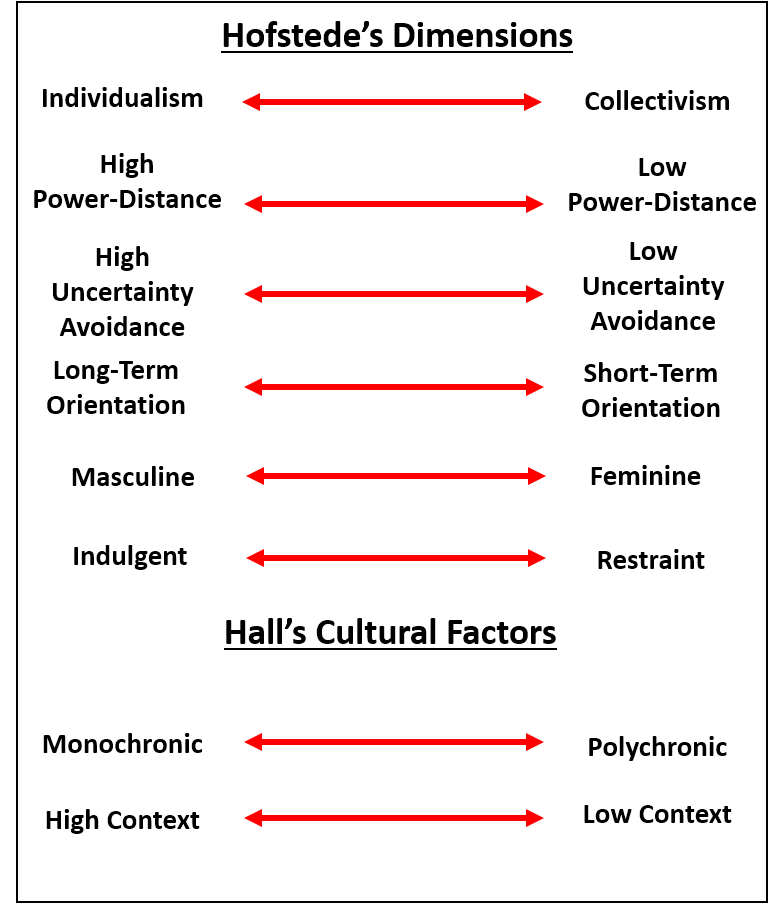

Individualism and Collectivism

According to Hofstede,

According to Hofstede,

The left side of this dimension, called Individualism, can be defined as a preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of themselves and their immediate families only. Its opposite, Collectivism, represents a preference for a tightly-knit framework in society in which individuals can expect their relatives or members of a particular in-group to look after them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. A society’s position on this dimension is reflected in whether people’s self-image is defined in terms of “I” or “we” (Hofstede, 2012a).

In a highly individualistic culture, members are able to make choices based on personal preference with little regard for others, except for close family or significant relationships. They can pursue their own wants and needs free from concerns about meeting social expectations. The United States is a highly individualistic culture. While we value the role of certain aspects of collectivism such as government, social organizations, or other forms of collective action, at our core we strongly believe it is up to each person to find and follow their path in life.

In a highly collectivistic culture, just the opposite is true. It is the role of individuals to fulfill their place in the overall social order. Personal wants and needs are secondary to the needs of the society at large. There is immense pressure to adhere to social norms, and those who fail to conform risk social isolation, disconnection from family, and perhaps some form of banishment. China is typically considered a highly collectivistic culture. In China, multigenerational homes are common, and tradition calls for the oldest son to care for his parents as they age.

High Power-Distance and Low Power-Distance

Power is a normal feature of any relationship or society. How power is perceived, however, varies among cultures:

Power is a normal feature of any relationship or society. How power is perceived, however, varies among cultures:

The power distance dimension of culture expresses the degree to which the less powerful members of a society accept and expect power to be distributed unequally. The fundamental issue is how a society handles inequalities among people. People in societies exhibiting a large degree of power distance accept a hierarchical order in which everybody has a place and which needs no further justification. In societies with low power distance, people strive to equalize the distribution of power and demand justification for inequalities of power (Hofstede, 2012a).

In high power-distance cultures, the members accept some having more power and some having less power, and that this power distribution is natural and normal. Those with power are assumed to deserve it, and likewise those without power are assumed to be in their proper place. In such a culture, there will be a rigid adherence to the use of titles, “Sir,” “Ma’am,” “Officer,” “Reverend,” and so on. The directives of those with higher power are to be obeyed, with little question.

In low power-distance cultures, the distribution of power is considered far more arbitrary and viewed as a result of luck, money, heritage, or other external variables. For a person to be seen as having power, something must justify their power. A wealthy person is typically seen as more powerful in western cultures. Elected officials, like United States Senators, will be seen as powerful since they had to win their office by receiving majority support. In these cultures, individuals who attempt to assert power are often faced with those who stand up to them, question them, ignore them, or otherwise refuse to acknowledge their power. While some titles may be used, they will be used far less than in a high power-distance culture. For example, in colleges and universities in the U.S., it is far more common for students to address their instructors on a first-name basis, and engage in casual conversation on personal topics. In contrast, in a high power-distance culture like Japan, the students rise and bow as the teacher enters the room, address them formally at all times, and rarely engage in any personal conversation.

High Uncertainty Avoidance and Low Uncertainty Avoidance

As you have already learned in this course, humans do not like uncertainty, and the drive to lower uncertainty to increase predictability and comfort is quite strong. How cultures handle uncertainty varies:

As you have already learned in this course, humans do not like uncertainty, and the drive to lower uncertainty to increase predictability and comfort is quite strong. How cultures handle uncertainty varies:

The uncertainty avoidance dimension expresses the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. The fundamental issue here is how a society deals with the fact the future can never be known: should we try to control the future or just let it happen? Countries exhibiting strong [uncertainty avoidance] maintain rigid codes of belief and behavior and are intolerant of unorthodox behavior and ideas. Weak [uncertainty avoidance] societies maintain a more relaxed attitude in which practice counts more than principles (Hofstede, 2012a).

Consider how one avoids uncertainty: by limiting change, adhering to tradition, and sticking to past practice. High uncertainty avoidance cultures place a very high value on history, doing things as they have been done in the past, and honoring stable cultural norms. Even though the U.S. is generally low in uncertainty avoidance, we can see some evidence of a degree of higher uncertainty avoidance related to certain social issues. As society changes, there are many who will decry the changes as they are “forgetting the past,” “dishonoring our forebears,” or “abandoning sacred traditions.” In the controversy over same-sex marriage, the phrase “traditional marriage” is used to refer to a two person, heterosexual marriage, suggesting same-sex marriage is a violation of tradition. Changing social norms creates uncertainty, and for many change is very unsettling.

In a low uncertainty avoidance culture, change is seen as inevitable, normal, and even preferable to stasis. In such a culture innovation in all areas is valued, whether it be in technology, business, social norms, or human relationship. Businesses in the U.S. that can change rapidly, innovate quickly, and respond immediately to market and social pressures are seen as far more successful. While Microsoft™ has long dominated the world market in computer operating systems, they are regularly criticized for being slow to change and to respond to changing consumer demands, which suggests a high uncertainty avoidance culture within that business. Apple™, on the other hand, has been praised for its innovation and ability to respond more quickly to market demands, suggesting a low uncertainty avoidance culture.

Long-Term Orientation and Short-Term Orientation

People and cultures view time in different ways. For some, the “here and now” is paramount, and for others, “saving for a rainy day” is the dominant view.

People and cultures view time in different ways. For some, the “here and now” is paramount, and for others, “saving for a rainy day” is the dominant view.

The long-term orientation dimension can be interpreted as dealing with society’s search for virtue. Societies with a short-term orientation generally have a strong concern with establishing the absolute Truth. They are normative in their thinking. They exhibit great respect for traditions, a relatively small propensity to save for the future, and a focus on achieving quick results. In societies with a long-term orientation, people believe that truth depends very much on situation, context and time. They show an ability to adapt traditions to changed conditions, a strong propensity to save and invest, thriftiness, and perseverance in achieving results (Hofstede, 2012a).

In a long-term culture, significant emphasis is placed on planning for the future. For example, the savings rates in France and Germany are 2-4 times greater than in the U.S., suggesting cultures with more of a “plan ahead” mentality (Pasquali & Aridas, 2012). These long-term cultures see change and social evolution are normal, integral parts of the human condition.

In a short-term culture, emphasis is placed far more on the “here and now.” Immediate needs and desires are paramount, with longer-term issues left for another day. The U.S. falls more into this type. Legislation tends to be passed to handle immediate problems, and it can be challenging for lawmakers to convince voters of the need to look at issues from a long-term perspective. With the fairly easy access to credit, consumers are encouraged to buy now versus waiting. We see evidence of the need to establish “absolute Truth” in our political arena on issues such as same-sex marriage, abortion, and gun control. Our culture does not tend to favor middle grounds in which truth is not clear-cut.

Masculine and Feminine

Expectations for gender roles are a core component of any culture. All cultures have some sense of what it means to be a “man” or a “woman.” Masculine cultures are traditionally seen as more aggressive and domineering, while feminine cultures are traditionally seen as more nurturing and caring. Hofstede (2012a) states:

Expectations for gender roles are a core component of any culture. All cultures have some sense of what it means to be a “man” or a “woman.” Masculine cultures are traditionally seen as more aggressive and domineering, while feminine cultures are traditionally seen as more nurturing and caring. Hofstede (2012a) states:

The masculinity side of this dimension represents a preference in society for achievement, heroism, assertiveness and material reward for success. Society at large is more competitive. Its opposite, femininity, stands for a preference for cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life. Society at large is more consensus-oriented.

In a masculine culture, such as the U.S., winning is highly valued. We respect and honor those who demonstrate power and high degrees of competence. Consider the role of competitive sports such as football, basketball, or baseball, and how the rituals of identifying the best are significant events. The 2017 Super Bowl had 111 million viewers, (Huddleston, 2017) and the World Series regularly receives high ratings, with the final game in 2016 ending at the highest rating in ten years (Perez, 2016).

More feminine societies, such as those in the Scandinavian countries, will certainly have their sporting moments. However, the culture is far more structured to provide aid and support to citizens, focusing their energies on providing a reasonable quality of life for all (Hofstede, 2012b).

Indulgence and Restraint

A more recent addition to Hofstede’s dimensions of culture, the indulgence/restraint continuum addresses the degree of rigidity of social norms of behavior. He states:

A more recent addition to Hofstede’s dimensions of culture, the indulgence/restraint continuum addresses the degree of rigidity of social norms of behavior. He states:

Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms (Hofstede, 2012a).

Indulgent cultures are comfortable with individuals acting on their more basic human drives. Sexual mores are less restrictive, and one can act more spontaneously than in cultures of restraint. Those in indulgent cultures will tend to communicate fewer messages of judgment and evaluation. Every spring thousands of U.S. college students flock to places like Cancun, Mexico, to engage in a week of fairly indulgent behavior. Feeling free from the social expectations of home, many will engage in some intense partying, sexual activity, and fairly limitless behaviors.

Cultures of restraint, such as many Islamic countries, have rigid social expectations of behavior that can be quite narrow. Guidelines on dress, food, drink, and behaviors are rigid and may even be formalized in law. In the U.S., a generally indulgent culture, there are sub-cultures that are more restraint focused. The Amish are highly restrained by social norms, but so too can be inner-city gangs. Areas of the country, like Utah with its large Mormon culture, or the Deep South with its large evangelical Christian culture, are more restrained than areas such as San Francisco or New York City. Rural areas often have more rigid social norms than do urban areas. Those in more restraint-oriented cultures will identify those not adhering to these norms, placing pressure on them, either openly or subtly, to conform to social expectations.

In addition to these 6 dimensions from Hofstede, anthropologist Edward T. Hall identified two more significant cultural variations (Raimo, 2008).

Monochronic and Polychronic

Another aspect of variations in time orientation is the difference between monochronic and polychronic cultures. This refers to how people perceive and value time.

Another aspect of variations in time orientation is the difference between monochronic and polychronic cultures. This refers to how people perceive and value time.

In a monochronic culture, like the U.S., time is viewed as linear, as a sequential set of finite time units. These units are a commodity, much like money, to be managed and used wisely; once the time is gone, it is gone and cannot be retrieved. Consider the language we use to refer to time: spending time; saving time; budgeting time; making time. These are the same terms and concepts we apply to money; time is a resource to be managed thoughtfully. Since we value time so highly, that means:

- Punctuality is valued. Since “time is money,” if a person runs late, they are wasting the resource.

- Scheduling is valued. Since time is finite, only so much is available, we need to plan how to allocate the resource. Monochronic cultures tend to let the schedule drive activity, much like money dictates what we can and cannot afford to do,

- Handling one task at a time is valued. Since time is finite and seen as a resource, monochronic cultures value fulfilling the time budget by doing what was scheduled. Compare this to a financial budget: funds are allocated for different needs, and we assume those funds should be spent on the item budgeted. In a monochronic culture, since time and money are virtually equivalent, adhering to the “time budget” is valued.

- Being busy is valued. Since time is a resource, we tend to view those who are busy as “making the most of their time;” they are seen as using their resources wisely.

In a polychronic culture, like Spain, time is far, far more fluid. Schedules are more like rough outlines to be followed, altered, or ignored as events warrant. Relationship development is more important, and schedules do not drive activity. Multi-tasking is far more acceptable, as one can move between various tasks as demands change. In polychronic cultures, people make appointments, but there is more latitude for when they are expected to arrive. David’s appointment may be at 10:15, but as long as he arrives sometime within the 10 o’clock hour, he is on time.

Consider a monochronic person attempting to do business in a polychronic culture. The monochronic person may expect meetings to start promptly on time, stay focused, and for work to be completed in a regimented manner to meet an established deadline. Yet those in a polychronic culture will not bring those same expectations to the encounter, sowing the seeds for some significant intercultural conflict.

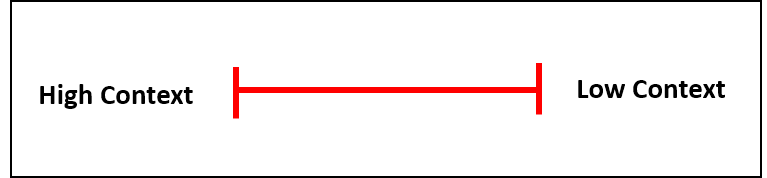

High Context and Low Context

The last variation in culture to consider is whether the culture is high context or low context. To establish a little background, consider how we communicate. When we communicate we use a communication package, consisting of all of our verbal and nonverbal communication. Our verbal communication refers to our use of language, and our nonverbal communication refers to all other communication variables: body language, vocal traits, and dress.

The last variation in culture to consider is whether the culture is high context or low context. To establish a little background, consider how we communicate. When we communicate we use a communication package, consisting of all of our verbal and nonverbal communication. Our verbal communication refers to our use of language, and our nonverbal communication refers to all other communication variables: body language, vocal traits, and dress.

In low-context cultures, verbal communication is given primary attention. The assumption is that people will say what they mean relatively directly and clearly. Little will be left for the receiver to interpret or imply. In the U.S. if someone does not want something, we expect them to say, “No.” While we certainly use nonverbal communication variables to get a richer sense of the meaning of the person’s message, we consider what they say to be the core, primary message. Those in a high-context culture find the directness of low-context cultures quite disconcerting, to the point of rudeness.

In high-context cultures, nonverbal communication is as important, if not more important, than verbal communication. How something is said is a significant variable in interpreting what is meant. Messages are often implied and delivered quite subtly. Japan is well known for the reluctance of people to use blunt messages, so they have far more subtle ways to indicate disagreement than a low-context culture. Those in low context cultures find these subtle, implied messages frustrating.

In summary, Hofstede’s Dimensions and Hall’s Cultural Variations give us some tools to use to identify, categorize, and discuss diversity in communication. As we learn to see these differences, we are better equipped to manage inter-cultural encounters, communicate more provisionally, and adapt to cultural variations.

While intended to show only broad cultural differences, these eight variables also can be useful tools to identify variations among individuals within a given culture. We can use them to identify sources of conflict or tension within a given relationship. For example, Keith tends to be a short-term oriented, indulgent, monochronic person, while his wife tends be long-term oriented, restrained, and more polychronic. Needless to say, they frequently experience their own personal “culture clashes.”

In our effort to become better communicators, understanding a few additional concepts is helpful. One of those is the distinction between race and ethnicity. Both of these terms are used in varied ways; neither is distinctly defined. Race is seen as a social construct that developed based on biological traits. Current findings in genetic studies show those traits are not as distinct as once thought. However, many communities and co-cultures have been based on race, and some of them developed distinct communication patterns in response to interactions with the dominant culture. People in those communities rely on codeswitching to alter their language use and behavior as they interact within their co-culture or within the dominant culture. Ethnicity is generally used to refer to traits associated with country of birth which may encompass language, religion, customs, or geographic location. Some people identify closely with their ethnic heritage, especially if their immigrant experience is more recent. Other aspects of cultural identity that play an important role in understanding intercultural communication are gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, social class, and generation. Students interested in learning more about those components may begin by identifying the values of their own cultures (both dominant and co-cultures).

Before looking at how to be more competent in intercultural interactions, it is important to identify some of the barriers. Verderber and MacGeorge (2016) give six:

- Anxiety:

While an intercultural situation will not necessarily result in culture shock, it is not unusual to experience some level of discomfort in such situations. The apprehension we feel can make the interaction awkward or can lead us to avoiding situations that we deem too unfamiliar. - Assumed similarity or difference:

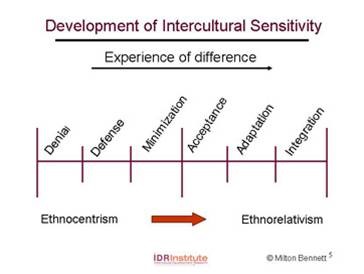

If we expect that restaurants will be the same in Asia as they are in the U.S., we are likely to be disappointed. Likewise, if we think no one in another country will understand us, we might miss the opportunity to connect with others who share similar interests. - Ethnocentrism:

Assuming our culture is superior to or more important than all others will make it difficult to successfully engage with people from other cultures. - Stereotyping:

We can create stereotypes of people within our culture or of people from other cultures. Either way it stops us from seeing people as individuals, and we instead see them as a certain age, race, gender, ability, or whatever. Stereotyping is a process of judging that we all need to work to avoid. - Incompatible communication code:

Even within our own language, we may have trouble understanding the messages of others. When the languages are different, it may be more difficult. Nonverbal communication also varies between cultures, so it is not always a good substitute for verbal communication. - Incompatible norms and values: People of one culture may be offended by the norms or values of another culture. For example, less-significant differences in values, such as which foods are most desired, may be offensive. For example, in India, cows are considered sacred, yet in the U.S., beef is widely consumed. However, different cultural values about business practices or expansion of territory can lead to international conflict.

Moving beyond those barriers and toward ethnorelativism is at the core of becoming a more competent intercultural communicator. Ethnorelativism is the knowledge that “cultures can only be understood relative to one another, and that particular behavior can only be understood within a cultural context” (Bennett, 1993, p. 46). The image below shows the Bennett Model that begins on the left with denial, meaning the person is unware the cultural differences exist or is avoiding contact with other cultures or worldviews (Bennett, 2011). As they progress to the right, individuals may move through phases of actually belittling other cultures (defense), indifference to cultural differences (minimization), accepting cultural differences without judging them, and adapting thinking and behaviors to operate successfully in a new culture before reaching integration in which one is comfortable interacting in a variety of cultures.

While few people truly reach the integration stage, anyone can strive to increase their intercultural communication competence. It takes time and effort, beginning with having an attitude of openness, respect, and curiosity. That leads to a desire to learn more about culture in general and about specific cultures, as well as an interest in learning new communication skills. Different cultures have different expectations for language use, nonverbals, and relationships. These can be learned through observation, language study, formal cultural study, or cultural immersion. The ultimate goals are to embrace a point of view that encourages you to see the value in other cultures, a provisional or ethnorelative view, and to be able to communicate effectively and appropriately in a new culture (Deardorff, 2006). To achieve this, it is key to value other cultures and respect people from all cultures.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture

- Individualism and Collectivism

- Power Distance

- Uncertainty Avoidance

- Time Orientation

- Masculine and Feminine

- Indulgence and Restraint

Barriers to Intercultural Competence

- Anxiety

- Assumed similarity or difference

- Ethnocentrism

- Stereotyping

- Incompatible communication code

- Incompatible norms and values

References

Research Institute. Retrieved 4/4/2017 from http://www.idrinstitute.org/allegati/IDRI_t_Pubblicazioni/47/FILE_Documento_Bennett_DMIS

12pp_quotes_rev_2011.pdf

hofstede.com/sweden.html

6th edition. New York: McGraw Hill.

2101 15th Ave NW

Willmar, MN 56201

(320) 222-5200

Keith Green, Ruth Fairchild, Bev Knudsen, Darcy Lease-Gubrud

Last Updated: August 7, 2018

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.