7 The Preparation

The Purposes of Public Speaking

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- describe how public speaking differs from Interpersonal Communication and Small Group Communication.

- explain the societal value of public speaking.

- explain the personal benefits to learning public speaking.

- apply the traits of a good speech in creating and presenting a speech.

- describe the general speech purposes.

The oldest form of public communication and the precursor to mass media is the simple act of one person rising and expressing their thoughts to the group. Public discourse is the foundation of society; it is how groups of people address and resolve differences collectively and peacefully. With the rise of democracy in Ancient Greece, the value of public speaking gained prominence. A citizen’s ability to speak their mind in public was highly valued and a sign of civic engagement.

Although we have so many avenues to express ourselves, from in person to online, the ability to craft and share a thoughtful, intelligent message is still an important skill. For a person’s career, civic involvement, and political engagement, becoming proficient in public speaking is a highly valuable.

The Nature of Public Speaking

Public speaking has three striking characteristics that set it off from interpersonal communication and small group communication.

First, public speaking is the act of one person speaking to many. Instead of focusing on an interactive nature, public speaking focuses on one person, the speaker, developing and presenting a message to a group of individuals.

Second, public speaking is a more formal presentation, meaning it is bound by specific strategies and techniques. Good public speaking requires more planning, development, and self-reflexivenessThoughtfully making choices about the most appropriate communication methods. See Module I, Section 1., than the other two contexts.

Third, in the other two contexts, we see all members communicating from a position of shared, equal responsibility. In public speaking, the speaker bears more responsibility as the message is one-directional, and the feedback the speaker receives from the audience is subtler, such as facial expressions, body posture, and fidgeting. Public speaking is still an interaction, just like interpersonal and small group, but the responsibility for success is less balanced with more responsibility being placed on the speaker.

The Value of Public Speaking

Given the fear that most people have of public speaking, it is reasonable to ask why we engage in such an intimidating process. The fear of public speaking is common, often ranked as one of the top fears we have. A Gallup poll from 2001 found that 40% of respondents listed public speaking as their greatest fear, second only to a fear of snakes. Given a choice, people preferred dying over giving a speech. Even with this high degree of anxiety, public speaking retains a valuable place in our culture for several reasons.

Societal Functions

Public speaking has a long, illustrious history in the United States. The very formation of the U.S. political system and society is firmly rooted in wise people speaking their minds in public settings, engaging in spirited debate and discussion, and working collaboratively to find the best path for the country. Our country is founded on the premise that individuals, working together, can govern themselves. Public speaking is the tool by which this process occurs.

Public speaking allows for the relatively quick dissemination of information to a group of individuals.

If a person has much to share with a group, presenting the information via public speaking can be a fast process. A classroom lecture is a typical example. However, a question that begs to be asked is how effective such dissemination is in achieving this goal. In lecture, approximately 5-15% of the material is retained by the student; hence, the speaker (the teacher in this case) must realize this limitation and be willing to use public speaking as a starting point, using other follow up methods to enhance retention of the information.

Public speaking allows individuals or groups to attempt to bring about social or political change.

We have a long history in this country of using our freedom of speech to change what we don’t like. The women’s movement and the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century, and the TEA party movement of the early 21st century are examples of such a process occurring. Individuals see something happening around them they do not like, and they use public speaking to make others aware of the problem and advocate a way to change the situation.

Public speaking allows communities to express common goals, concerns, and values.

We see speeches of commemoration at Memorial Day, Veteran’s Day, and the Fourth of July. The speeches remind us of who we are as a nation, and they express common values. Attending a Sunday sermon is the same. Churches, mosques, and synagogues exist for a group of individuals to share common values and worldviews. The sermon is the central feature which pulls the community members together, the faith leader giving voice to that common world view.

Public speaking allows members of a democratic society, such as the United States, to actively debate issues of concern.

We tend to take for granted our First Amendment right to openly and clearly disagree with our governmental structures on issues of concern. We have the legal right, and obligation some would say, to speak out in opposition to those things with which we disagree. Except for advocating violence, we can speak out against our mayors, governors, and presidents, and no one has the right to squelch our voice. When we speak out in a public forum, we are participating in the process of self-governance by exercising our freedom of speech.

Personal Benefits

In addition, to the role of public speaking in our American society, becoming competent as a public speaker benefits us personally.

Managing Anxiety

Given the anxiety about public speaking, and our need to confront and manage that anxiety, we build self-confidence. Accepting and working with our speech anxiety gives us experience in facing situations in which we are being judged and evaluated. Learning how to confront fear in public speaking gives us tools to use to confront fears in other situations as well.

Managing Our Self-Presentation

We learn to monitor and manage our self-presentation. Since the vast majority of communication occurs nonverbally, a competent public speaker knows how to manage their entire physical package to present themselves most effectively, confidently, and powerfully. Just as with confronting our anxiety, being able to self-reflexively manage our self-presentation carries over into all aspects of our professional and personal lives. Although talent and ability is a significant part of career success, communication ability sets people off as especially competent and professional. The ability to engage in effective self-presentation can be a deciding factor in getting a job, being successful in the job, and advancing in our careers.

Packaging Information for Others

We learn how to package information to benefit others. Good speakers are highly receiver-oriented. We are very concerned about giving thoughtful, well organized, easily followed, and engaging presentations. The ability to create messages fitting these standards will serve any of us well in a variety of professional and personal settings. Many people have good ideas, but not everyone can communicate them well to others. In public speaking, we learn how to package our message to best fit the audience we have at the moment.

A “Good” Speech

Unfortunately, for most people our exposure to public speaking has left us with a distorted view of what makes a “good” speech. Virtually anytime we ask a class, “What is the first thing that comes to mind when you think of listening to a speech,” the answer is “boring.” This does not have to be the case; it is the job of the speaker to make choices that directly influence how interesting or boring a speech is going to be.

As speakers, we have the obligation and ability to choose how effectively and dynamically we will present ourselves and the information to the audience. We can give interesting, dynamic, energetic, and engaging speeches. Each of us has experienced teachers who were boring and monotone, but we have also experienced teachers who were dynamic and energetic. The latter group chose to make the speeches (lectures) more interesting. To make a speech more interesting and effective, we need to understand what makes a good speech:

- A good speech is well structured and signposted to enhance clarity and memory value. A good speech is organized and easily followed with clear, obvious transitions. Our job as speakers is to present a message clearly and thoughtfully, and clear structure facilitates that.

- A good speech sounds like “organized conversation.” The phrase is meant to invoke the image of a speaker presenting naturally and comfortably; just talking to the audience, in an organized, easily followed manner.

- A good speech has a purpose, clear to the audience and to which the speaker adheres. Good speakers make their purpose clear and they fulfill that. They do not wander, drift about, shift purposes, or mislead the audience. They do not start off informing the audience, and then suddenly shift to persuasion.

- A good speaker is active, not passive. Too many speakers, especially novice speakers, tend to use the “open my mouth, let the words fall out” approach to speaking. This thoughtless approach to public speaking is not very effective. Good speakers make choices, determining throughout their speech the best strategy for the given audience. Through the preparation and practice process, we make decisions based on what we think will increase the likelihood of success. Such strategic thinking requires careful consideration of the topic, the audience, the speaker, and knowledge of the interaction of these three components.

- A good speaker works to create immediacy with the audience. Immediacy is a sense of connection; that the speaker, the topic, and the audience are all working together. Good speakers see a speech as a time to share a message with an audience, building a bridge between the speaker and the audience. Too often novice speakers see the audience as a barrier to success, a collective of judgmental individuals out to embarrass the speaker. However, that is simply not true of most audiences. Audiences want the speech to be good because it validates the time spent listening, it is more enjoyable, and it simply makes the time go faster. If a speaker taps into the audience’s interests and personality, they can be quite effective in engaging the audience. Such engagement does not happen automatically; it is the result of thoughtful planning and preparation.

Watch The 7 Secrets of the greatest speakers in history | Richard Greene | TEDxOrangeCoast [18:24].

The public speaking situation is quite different from interpersonal communication and small group communication. The degree of advanced planning, of conscious decision making, and of communicator responsibility is much higher when giving a speech. We have been taught when a person goes to the front of the room to speak, the speaker is now “in charge” of the event. We must meet that expectation, take charge of the event, and fulfill our responsibilities for success. Speeches are only as good as the audience thinks they are; the speaker must rise to the challenge of presenting a good speech.

General Speech Purposes

When developing a speech, we need to know why we are speaking. Even before considering the topic, we need to know if our purpose is to inform, to persuade, to entertain, or if it is a special occasion.

Speeches to Inform

Speeches to inform are those in which we are aiming to enlighten or to further educate the audience, but in an objective, non-directive manner. We provide the information about the topic to the audience, but we are not directing the audience to believe, feel, or act in a specific manner.

There are three types of informative speeches.

- Report speech. A speech to report is one in which we take a single body of information, analyze it for the important points, then present a summary of those important points. This is common in a business setting. For example, if ACME Industries is considering making and selling a new product, various divisions will do research to determine the likelihood of the product being a success and profitable. Once this feasibility research is done and compiled into a single report, a single person or a group will then present the key findings to the management so they can decide on the course of action to take.

- Demonstration speech. These are classic “how to” speeches, usually arranged in a step-by-step pattern. For example, Mary may give a speech on how to be creative with Ramen noodles. She will progress, chronologically, through a series of steps the audience can then follow on their own.

- Explanation speech. Speeches of explanation are presentations drawing from multiple sources, designed to generally enlighten the audience about a given topic. They are not designed to show how to do something, but are for generally increasing the audience’s knowledge about the topic. Instead of speaking on how to make Ramen noodles, Mary may explain how good nutrition aids classroom performance in college.

Speeches to Persuade

Speeches to persuade are those in which we are aiming to influence the audience in some fashion. They are subjective and highly directive. The speaker has a bias toward a specific belief, attitude, or action, and the speaker works to direct the audience in what to believe, what opinion to have, or what action to undertake.

In persuasion, the issue of ethics becomes paramount. Some students erroneously believe that speakers always have to give both sides of the issue to be ethical, but that is not true. When Lisa shops for a car, she knows the salesperson is out to persuade her to buy; thus, she expects messages designed to urge her to that action. As long as the salesperson gives accurate, verifiable, and truthful information, there is no ethical violation.

It is our job to provide the audience with the most accurate information we can find, and to present that information honestly, not distorting it. We must cite our sources to give due credit, and the topic should be one that can be justified as beneficial to the audience, not just to the speaker.

There are three types of persuasive speeches.

- Persuasive speeches to influence beliefs. A belief is what we hold to be true or false. For example, the knowledge that the Earth rotates around the sun is a belief; we believe it to be factual information. The idea that smoking can cause cancer is a belief. If we try to persuade the audience consuming too much fat can cause colon cancer, we are trying to get the audience to believe what is true or false about the impact of fat in our diets.

- Persuasive speeches to influence attitudes. We attempt to influence how an audience judges an event or idea; the speaker is trying to influence the audience’s opinion of something. For these speeches, the speaker is attempting to make the audience think of the topic on a scale of good to bad, or desirable to not desirable. To argue the Governor of Minnesota is doing a good job (or a bad job) is an attempt to influence an attitude or opinion. With statements like these it is not a matter of true or false, black or white. It is a matter of placing the Governor on a range of opinion from highly positive to highly negative.

- Persuasive speeches of actuation (or action). We try to get the audience to engage in a specific behavior. Advertising is a prime example. We are asked to have a positive opinion of a product, and then to act by purchasing.

The three types of persuasive speeches build on each other. If Yousef is going to give a speech of actuation calling for the audience to donate blood during Ridgewater College’s annual blood drive, he will need to show the audience there is a need for blood (a belief), that donating blood is a good thing to do (an attitude), and how to participate in the blood drive (an action).

Speeches to Entertain

Although not commonly done in an introductory Communication Studies class, there is a third general speech purpose: a speech to entertain. We would hope all speeches are entertaining in some fashion, whether through humor, interest, or seriousness, so the audience found the speech engaging and intriguing. A true speech to entertain, however, is one in which the primary focus is to generate laughter. In other words, they are speeches intended to be funny.

These are still speeches in that they are organized, have a clear structure, and flow well, but they have as their overall goal the creation of laughter in the audience. The speaker usually has an underlying serious informative or persuasive point, but it is explored and developed through the use of humor. Commencement addresses, especially by those delivered by comedians or comic actors, like Tom Hanks, are typically structured this way. The speaker has a serious point to make but develops it in a humorous manner. These are common at events such as celebratory dinners or awards banquets.

Special Occasion Speeches

A special occasion speech is just what the name states: speeches given at special events. This is actually a very common type of speaking. Special occasion speeches are designed to fit the specific event at which they are being given. While each one has its own unique guidelines, the key point is to develop the speech consistent with that occasion.

Some common special occasion speeches include:

Eulogy: a speech given at a funeral or memorial service to honor the deceased.

Introduction: a speech given to introduce a speaker to an audience.

Toast: a speech given honoring a person or group, such as a wedding toast.

Giving an Award: a speech given to bestow an honor on a person.

Accepting an Award: a speech given to communicate appreciation for an award.

Commencement: a speech given at a graduation, typically addressing the past (the work done to acheive the goal) and the future (challenging the graduates to learn more, help others, get involved in social issues, or otherwise continue personal growth).

Generally special occasion speeches are fairly short and focused on the event at hand. Humor is commonly used, even with many eulogies, but only when appropriate for the event and audience.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

The Value of Public Speaking

References

Gallup. ( 2001, March 19). Snakes Top List of Americans’ Fears. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/1891/snakes-top-list-americans-fears.aspx

Audience Analysis

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- use the three stages of audience analysis to determine the dynamics of a given audience.

- describe the core demographic characteristics of an audience.

- make inferences to describe the key traits of an audience.

- determine how to adapt an informative speech to an audience.

- determine how to adapt a persuasive speech to an audience.

- adapt the presentation to the demands of the venue.

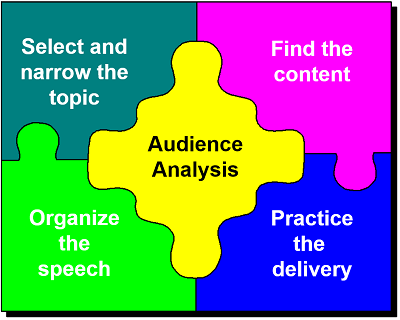

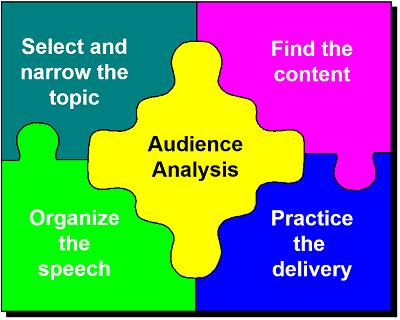

A good way to think of developing a speech is to think of it like a puzzle. There are multiple pieces that all have to fit together, with the driving piece being the audience. The core of a good presentation is an understanding of the audience to whom the speech is targeted. We need to spend some time gaining an understanding of our audience which becomes the criteria to determine the best strategies and approaches to employ.

The Stages of Audience Analysis

In order to get a sense of the audience’s personality, we do an audience analysis. In such a process, we identify key factors of the audience to help us determine the best approach to take in crafting our message. There are three stages in the audience analysis process.

1. Gathering Information

The first stage, gathering information, can be as simple as observing who is in the audience, or can be a more involved process of formalized data collection. For classroom speeches, simply look around the room and determine some basic data, such as:

Average Age

Gender Distribution

Education Level

Probable Income Level

Relationship Status

Parental Status

For situations in which the speaker is invited to speak, ask the person extending the invitation about the audience: Who are they? Why are they gathered? What are their expectations? With this basic information, we can move to the next stage, making inferences.

2. Making Inferences

At this stage, we are trying to get a handle on the audiences’ collective “personality.” To do this, we make inferences. An inference is an conclusion based on evidence and reasoning. An inference is not a guess; a guess is more random while an inference is based on specific bits of information. For instance, if it is December and the wind is blowing, those of us living in colder climates, like Minnesota, will infer, “It’s cold outside.” That conclusion is based on combining experience with bits of evidence to draw a reasonable conclusion.

At this stage, we are trying to get a handle on the audiences’ collective “personality.” To do this, we make inferences. An inference is an conclusion based on evidence and reasoning. An inference is not a guess; a guess is more random while an inference is based on specific bits of information. For instance, if it is December and the wind is blowing, those of us living in colder climates, like Minnesota, will infer, “It’s cold outside.” That conclusion is based on combining experience with bits of evidence to draw a reasonable conclusion.

We can do the same thing with audiences. Now that we have gathered some demographic data, we can move on and make inferences as to what the data tells us about the audience. The most any speaker can consider are the common denominators, those things we believe are true of the vast majority of our audience members.

For example, one common denominator is they are all in attendance for the speech. Why are they there? Are they attending because they came of their own free will, such as attending a religious service. Or are they in attendance because it is mandated by their job? Or is it somewhere in between, such as a college classroom, in which students voluntarily sign up for the class yet are required to attend by the instructor? Knowing the basis of why they are there gives the speaker a sense of what the audience is expecting and the attitudes they are likey holding. For a truly voluntary audience, the speaker has an audience anxious to hear what they say and will generally be quite attentive to the message. For a mandated audience, the speaker is facing an audience that may resent being present and assumes the presentation will be boring or irrelevant. For such an audience, the speaker will need to focus on gaining interest and building relevance. For the blended audience, the speaker can generally assume a degree of interest if the information is presented in an interesting manner.

For example, one common denominator is they are all in attendance for the speech. Why are they there? Are they attending because they came of their own free will, such as attending a religious service. Or are they in attendance because it is mandated by their job? Or is it somewhere in between, such as a college classroom, in which students voluntarily sign up for the class yet are required to attend by the instructor? Knowing the basis of why they are there gives the speaker a sense of what the audience is expecting and the attitudes they are likey holding. For a truly voluntary audience, the speaker has an audience anxious to hear what they say and will generally be quite attentive to the message. For a mandated audience, the speaker is facing an audience that may resent being present and assumes the presentation will be boring or irrelevant. For such an audience, the speaker will need to focus on gaining interest and building relevance. For the blended audience, the speaker can generally assume a degree of interest if the information is presented in an interesting manner.

Other inferences can be made as well. For example, given a college classroom of thirty, 18-20 year-old students, the following inferences generally hold true:

- Their personal income level is very low.

- They are not parents yet.

- While some may be in longer term relationships, most are not married nor engaged.

- They are interested in completing their education and establishing themselves in a moderately well-paying career.

- They tend to be more liberal than conservative.

- They tend to feel passionate about certain issues.

- While they are likely aware of current events generally, they are not typically aware of specific details.

- Socializing is a important activity.

- They are not very politically active.

Although we know these do not apply to each individual audience member, we are aiming to identify what we think is generally true about the audience overall. By making these inferences, we start to understand what is important to the audience. We have a sense of their values, interests, needs, and expectations which can serve as a target, helping us aim the speaker’s message more precisely. We use this information in the final stage of audience analysis, adapting the speech.

3. Adapting the Speech

The final step, adapting the speech, is the key to using an audience analysis to enhance the chance of success. It really does not matter how well we complete steps 1 and 2, if we do not take the information and act upon it, the speech is much less likely to succeed.

In adapting the speech, we are considering how to package the information for the audience; determining the best approach or strategy for accomplishing the speaker’s goal. This does not mean the speaker must alter their core message. Instead, it means to take the core message and package it in a manner more interesting to the audience.

For example, if doing a speech on sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) to two audiences, 10th graders and college freshmen, the same basic information can be communicated, but it would be packaged differently. For the 10th graders, more formal, medical terms would be used, less humor would be used, and since the speaker needs to consider parents, the speaker should assume the audience is not currently engaging in intercourse. For the college audience, however, more lay terms could be used, more humor could be used, and the speaker could safely assume the audience members, in general, are more sexually active. Notice, the basic information does not change, but the packaging changes.

Everything in the speech should be considered as to its fit with the audience. What kind of attire is the audience expecting: formal, casual, or in-between? Is the audience expecting a very animated, active delivery with lots of movement and energy, or are they expecting a more subdued, more thoughtful delivery style? Is the language level to be formal and high level? Or is a more casual language level acceptable?

Which sources should the speaker seek out? For an audience with a lot of specific knowledge on the speaker’s topic, higher level, very specific, highly qualified sources will be needed. For an audience with less specific knowledge, more casual sources may suffice. If informing an audience of physicians on the latest discoveries in the treatment of lung cancer, very specific medical research sources are needed. However, if informing an audience of college students on the same topic, general interest sources, such as newspapers or magazines, will be sufficient.

Everything in the speech must be considered in light of the audience. Some variables may arise as more important than others. For one audience, the quality of sources may be paramount to the success of the speech, yet for another audience, the quality of delivery may be most important. Through carefully considering the dynamics of the audience, a speaker can make self-reflexive choices to increase the chance of success.

Audience Adaptation for Informative Speaking

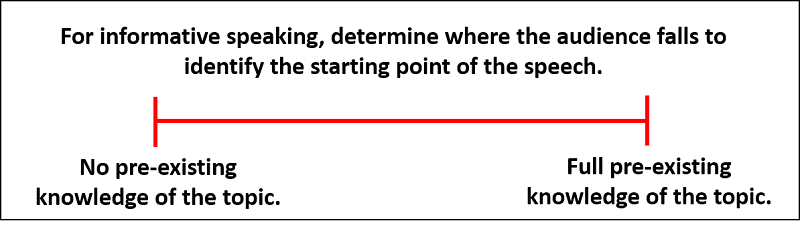

When adapting to an audience for informative speaking, it is vital we have some idea of where the audiences’ existing knowledge is on the topic. Remember, If we were to compare individual audience members, we would find a range, but we have to aim for average or middle ground.

Once we have an idea of what middle ground is, we use that to determine where to focus the speech.

We do not want to focus the speech below the audiences’ existing knowledge level. If we do so, the audience may be bored or may even become offended, perceiving the speaker as being patronizing. Likewise, we cannot start the speech above the audiences’ existing knowledge as they will not know what we are talking about and will not be able to follow the speech. They will not be able to make the leap from their existing knowledge to the starting point of the speech. The ideal place to start is at their existing level of knowledge, and then we move them forward.

Audience Adaptation for Persuasive Speaking

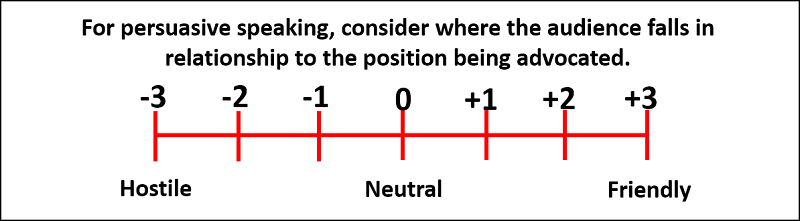

When adapting to an audience for persuasive speaking, it is vital the speaker have an idea of the audiences’ existing attitude or position on the topic, and how that compares with the speaker’s. As with any audience, we know the attitudes will range, but again we are looking for the average attitudinal position.

There are three general types of audiences for persuasion: hostile, neutral and friendly.

- A hostile audience is one that already disagrees with the speaker’s position. With a hostile audience, it is vital to know why they disagree because those are the reasons we need to address. If we do not address the key issues, the audience will be left holding their hostile position. The speaker also needs to consider how to approach the issues to avoid offending the audience. The speaker needs to respect the audience’s position and tactfully offer a contrary position.

- A neutral audience is usually a group who does not really know anything about the topic; they have yet to form an opinion on the topic. We have two jobs: “inform” the audience, and persuade them to accept our position. However, “informing” in this case will not be as objective as a pure informative speech would be. Rather, we introduce the audience to the topic in a manner consistent with the position we are advocating. Then we offer the audience reasons to accept the position being advocated.

- A friendly audience is one who largely agrees with the speaker’s position, but not completely. For these audiences, we must identify, as specifically as possible, why the audience is not in complete agreement, and then focus on those points of difference to move the audience to the position being advocated. For example, most people believe that donating blood is a good idea, yet only a fraction of those eligible actually donate. They are friendly to the idea, but they are not engaging in the action. The speaker needs to determine why they are not taking that final step and focus the speech in those areas.

Keep in mind that if the audience totally agrees with the speaker’s position at the outset, there is little point in trying to “persuade” them as there is no place for them to move, nothing to change, since they already agree with the speaker’s position. In this situation, we would give more of a motivational speech to remind the audience of their agreement with our position.

Consider the Venue

The venue of the speech is the space in which the speech will be given. Each venue will place its own limitations and demands on how the speech will be given. Just as we need to adapt the content of the speech to the audience, we also need to make appropriate plans for the location. The possible factors affecting the speech vary widely, but some common ones include the size of the space, the availability of technology, and arrangement.

The venue of the speech is the space in which the speech will be given. Each venue will place its own limitations and demands on how the speech will be given. Just as we need to adapt the content of the speech to the audience, we also need to make appropriate plans for the location. The possible factors affecting the speech vary widely, but some common ones include the size of the space, the availability of technology, and arrangement.

First, one thing the size of the space will determine is the need for a sound system. If the speaker is to use a microphone, will it be affixed to a lecturn? Will it be handheld? Will it be a body microphone worn like a headset? Is it wireless or wired? The answer to any of these questions impacts how the speech will be given. For instance, if the microphone is attached to the lecturn, the speaker must remain fixed in one location and must be sure to always keep the microphone in front of their mouth. If the microphone is handheld, the speaker will have one hand occupied at all times, so gesturing needs to be adapted.

Second, visual aid capabilities should be considered. If planning to use slideware, is there a projector and screen? How will the speaker get the slides to display: connect their own computer or use one provided by the location? How will they control the slides: a remote? Is the room organized so all audience members will be able to see the screen comfortably?

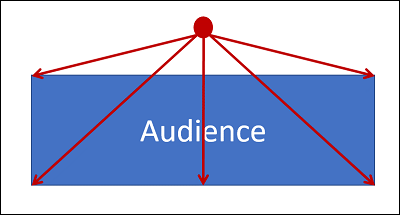

Third, the arrangement of the room may impact how the speaker engages the entire audience. For a flat, wide room, as in Image 8, the speaker will need to focus on scanning far left and far right to take in the entire audience. If possible, the speaker should move across the room to give each area of the audience priority focus for a time. If using a projected visual aid, audience members on the far edges may find it difficult to see, so the speaker will need to focus on making sure all understand what is being show.

Third, the arrangement of the room may impact how the speaker engages the entire audience. For a flat, wide room, as in Image 8, the speaker will need to focus on scanning far left and far right to take in the entire audience. If possible, the speaker should move across the room to give each area of the audience priority focus for a time. If using a projected visual aid, audience members on the far edges may find it difficult to see, so the speaker will need to focus on making sure all understand what is being show.

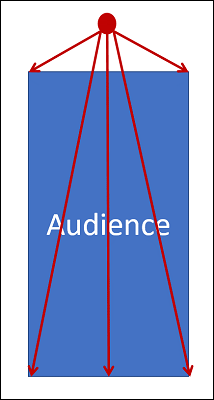

For a narrow, deep room, Image 9, the speaker will need to adjust volume and work to make sure the message, both spoken and visual, can reach the back row. Visual aids, and ideally the speaker, need to be elevated high enough for all to see.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Audience adaptation for informative speaking

Audience adaptation for persuasive speaking

The Topic and Thesis

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- explain how creating a speech is a holistic process.

- develop a speech in the proper order.

- create a speech using the appropriate lengths for sections.

- apply topic selection criteria to the selection of a topic for an audience.

- develop a specific speech purpose.

- translate a specific speech purpose into a properly worded thesis statement.

A Holistic Approach to Speech Development

Although there are “steps” to preparing a speech, a more appropriate way of thinking of speech preparation is as a dynamic process.

Although there are “steps” to preparing a speech, a more appropriate way of thinking of speech preparation is as a dynamic process.

Instead of seeing speech development as a linear process, it is better to see it as a holistic process of creating all components of the speech so they fit together as an effective whole. A puzzle metaphor demonstrates this approach.

As the model illustrates, the core of this dynamic process is the audience analysisSee Module VIII, Section 3, and the speech is built around our understanding of our audience. We then develop the content (selecting the topic, finding the content, and organizing the speech), and prepare the content for presentation (practice the delivery).

Although there is a sense of a linear process, sticking to some sort of artificial step process is not as important as making sure that all the pieces fit together as an effective, unified whole. Although we may have developed one area, as we prepare the whole speech, we may need to revisit earlier parts of the process and alter those to achieve a unified whole.

Parts of the Speech

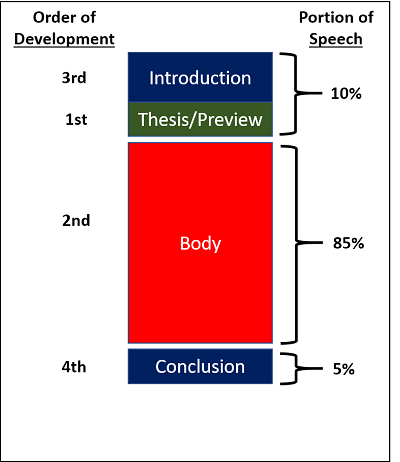

While there are a variety of ways to organize a speech, the most common structure breaks the speech into four parts:

While there are a variety of ways to organize a speech, the most common structure breaks the speech into four parts:

- Introduction

- Thesis/preview

- Body of the speech

- Conclusion

Portions of the Speech

The introduction, ending with the thesis/preview, comprises approximately 10% of the speech. The body of the speech is about 85% of the speech, and the remaining 5% is the conclusion.

The percentages should be used as guidelines for the speaker, not as absolutes. The majority of the speaker’s efforts should be focused on relating the core information or arguments the speaker needs to share and the audience is there to hear. Since the body of the speech contains this core information, most of the time should be spent in that area.

Order of development

In developing the speech, novice speakers often make the mistake of starting with the introduction. Since the introduction comes first, it seems logical to start there; however, this is wrong. Creating the thesis is the first step in good speech development. Until we know what the speech is about, we cannot effectively determine an introduction. Just as we cannot introduce a person we do not know, we cannot introduce a topic not yet developed. The most effective order of preparation is:

- Thesis. Since the thesis defines what the speech is about and what it is not about, developing it first helps guide the speaker in developing the body, doing research, and staying properly focused.

- Body. The body of the speech is the key content the audience is there to hear, so the speaker should spend a substantive amount of time researching, organizing, and fine-tuning this core content.

- Introduction. A speech introduction is the most creative part of the process. Since it is intended to pull the audience into the thesis and prepare them for the body, by waiting until after developing the body, the speaker will have a clear sense of what the introduction should do. During research for the body, it is common to come across a quotation, example, or some other idea for the attention getting device of the introduction.

- Conclusion. While it is the shortest part of a speech, it is very important as it is the last thing the audience will hear, leaving the audience with their final impression of the speech. This is developed last as there are ways to conclude a speech that are built on how the speaker begins the speech.

While this order of development is important, always remember the “puzzle” metaphor: we have to work to make all the parts fit together, so there can be a lot of revisiting parts to alter or fine tune them. Speech development is a dynamic process in which changing one part of the speech may have a ripple effect, affecting other parts. In the end, a good speaker makes sure that the speech is consistent, coherent, organized, and flows well for the audience.

One of the most challenging steps classroom students face when given the classic speech assignment is to select and narrow a topic to fit the time limits of the assignment.

Topic Selection

Coming up with a topic “out of the blue” is quite difficult. Realistically, finding a topic for a classroom speech is far more difficult than finding one for a speech in a work or community setting.

Coming up with a topic “out of the blue” is quite difficult. Realistically, finding a topic for a classroom speech is far more difficult than finding one for a speech in a work or community setting.

The vast majority of presentations outside the classroom will be on topics in which the speaker is well versed and comfortable. If asked to speak, it will typically be to share knowledge within their field of expertise. If a business hires a Communication Studies instructor to present at a training session, they are clearly hiring them for expertise in communication. Even then, the speaker still has a responsibility to narrow to a specific topic, to adapt it to their audience and the occasion, and to fit the time limits. So outside of the initial step, determining the overall subject, speakers still have to go through the topic development process.

Topic Selection Criteria

In selecting a topic, one of the most common mistakes novice speakers make to take a sender-based approachSee Module I, Section 1. This is assuming the audience has a strong interest in the same things the speaker feels passionate about. Just because a speaker may be deeply into video gaming does not inherently mean the audience shares that interest. To select a good topic, the speaker needs to be receiver-basedSee Module I, Section 1 and objectively consider what is most likely to be successful. While the speaker’s interest can certainly serve as a good starting point to identify a general topic, the specific topic and approach to the topic must be carefully considered.

There are four criteria to determine the appropriateness of a topic:

- Audience InterestWe need to select a topic we think will appeal to the specific audience. This may be a topic we know the audience will have an immediate interest in, or one in which the audience will have an interest once we develop the topic to some degree. Being receiver-based, the speaker must be honest in their assessment of the topic and the audience, careful not to project their own interests on the audience.

- Speaker InterestAlthough audience interest is certainly key, the speaker must also have an interest in the topic. A lack of speaker interest can be deadly. If the speaker is unmotivated to develop and present the speech, the speech usually sounds as if the speaker is bored and does not care. The speaker loses their own sense of desire to do a good job. A good topic is one that has a healthy balance of audience interest and speaker interest.

- Occasion AppropriatenessWe need to consider why the audience is gathered and select a topic that fits the occasion. If the audience is gathered at a business conference, learning new ways of interacting with clients, an informative topic on some aspect of communication skill may be appropriate. For a commencement address, talking about the dire state of the economy may not fit the celebratory nature of the event; the topic should invoke growth, opportunity, and an optimistic future. We want our topic to complement the reason the audience is gathered.

- Time LimitsThe speaker must fit the speech into the given time limits. The speech needs to fill the allotted time, and yet it cannot exceed that given time. It is a core speaker responsibility to treat the audience with respect and to fill those time limits appropriately. Exceeding time limits is simply not an option. If a topic cannot be covered within a given time, the speaker has two options: limit the topic, or get a new topic.As we know from looking at culture, Americans are quite monochronicSee Module I, Section 1. We see time as a resource, like money, to be budgeted and spent wisely. When speeches end on time, we have gotten what we have paid for. If they run a little short, we may feel we got a deal, but if they run quite short, we feel we got cheated. The audience is spending their time on the speaker; give them their money’s worth. On the other end, if the speech runs overtime, the speaker is “stealing” time from the audience, taking our time resource without our permission. Time limits are very important in a monochronic culture.

Narrowing a Topic

Since the speaker needs to fit the speech into the allotted time, we need to move from a broader topic to a narrower, much more specific topic. Finding a specific topic is a process of analysis, selection, and narrowing. The goal of the process is to find a specific topic that fits the same criteria as discussed above: audience interest; speaker interest; occasion appropriateness; and time limits.

A good way to narrow the topic is to start with a broader topic and brainstorm a large list of sub-topics. Using the previous four criteria, narrow the topic to the best fit. If the topic is still too large, repeat the process as often as needed to reach a manageable size topic.

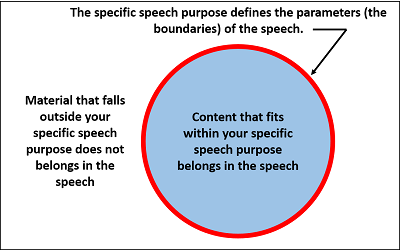

Specific Speech Purpose

After finding that specific topic, develop the specific speech purpose. The specific speech purpose is the narrow, focused direction the speech will be taking. The function of the specific speech purpose is twofold: to identify what goes in the speech, and to identify what does not go in the speech. The specific speech purpose establishes the parameters of the speech. We use the parameters as guidance as to what to include in the speech and what to keep out of the speech. This is an important consideration. Unless the speaker keeps a tight rein on the development of the speech, the speech can get out of control, suddenly diverting into a different area or expanding beyond the time limit.

After finding that specific topic, develop the specific speech purpose. The specific speech purpose is the narrow, focused direction the speech will be taking. The function of the specific speech purpose is twofold: to identify what goes in the speech, and to identify what does not go in the speech. The specific speech purpose establishes the parameters of the speech. We use the parameters as guidance as to what to include in the speech and what to keep out of the speech. This is an important consideration. Unless the speaker keeps a tight rein on the development of the speech, the speech can get out of control, suddenly diverting into a different area or expanding beyond the time limit.

For example:

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of how to write an effective resume.

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of alternative forms of financial aid.

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of creative ways of using macaroni and cheese.

For persuasion, the specific speech purposes would be slightly different, reflecting the idea of changing an audience’s belief, attitude, or action:

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to donate blood.

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to vote for the school referendum.

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to use a designated driver.

The Thesis

Once the specific speech purpose has been developed, we can easily create the thesis. The thesis is the specific, concise statement of intent for the speech. It is the one, single sentence clearly stating exactly what the speech will be addressing. Converting the specific speech purpose to the thesis is simple:

- “After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of how to write an effective resume.”becomes”Today I’ll take you through the steps of writing an effective resume.”

- “After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of alternative forms of financial aid.”becomes”There are several alternate forms of financial aid for you to consider.”

- “After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of creative ways of using macaroni and cheese.”becomes”I’ll show you several creative ways of using macaroni and cheese.”

- “After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to donate blood.”becomes”Today I’ll show you why it is important that you donate blood.”

- “After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to vote for the school referendum.”becomes”Voting for the upcoming school referendum is important for the success of our schools.”

- ” After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to use a designated driver.”becomes”When you go out partying, you should use a designated driver.”

There are several traits of a good speech thesis:

- Concise. The thesis is a simple, straightforward sentence clearly telling the audience what the speech is going to be about.

- Grammatically simple. There is one subject and one predicate; it is not a compound sentence, nor a compound-complex sentence. The thesis is not a question.

- Blatant. A speech thesis is more blunt and obvious than what we might use in writing.

- Identifies the parameters of the speech. It tells the audience what the speaker will be doing; which, by definition, also tells the audience what the speaker is not doing.

- Consistent with the speaker’s overall speech purpose. The wording reflects the proper informative or persuasive tone.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

The Body

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- explain the difference between writing a speech and constructing a speech.

- determine main points for a thesis.

- explain the importance of clear organization.

- use the appropriate pattern of arrangement for the body of the speech.

- use subordination and coordination to organize the body of the speech.

- incorporate transitions.

After doing an audience analysis, selecting a topic considering the audience’s needs and interests, and creating the thesis, we need to develop the body of the speech. The body is the largest component of the speech, about 85 percent, and where we actually do what the thesis says. In the body, the speaker gives the information or arguments necessary to fulfill the intention of the thesis.

When a student says, “I’m going to write my speech,” we cringe. The way we use language is different when spoken versus when written. Inevitably, if a student sits down to write a speech, they will slip into a written style of language, like they are writing a paper for class. However, when this written speech is presented orally, it will sound dull, awkward, and artificial; it will sound like someone reading a paper for class. Instead, we develop or create speeches. We work from outlines to plan the flow of ideas and to keep the oral style of language. Avoid writing out any more than necessary to keep the speech in a conversational style of language.

Read more about the differences between speaking and writing.

Most commonly, speeches are broken into 2-4 main points. Main points are the major subdivisions of the thesis. Having too many main points can be overwhelming to the audience; fewer main points are more manageable for the speaker and the listener. Imagine hearing a speaker say, “Today I want to review 14 types of financial aid.” Chances are most audience members would feel a sense of dread over how long they assume the speech will be. If, however, that speaker groups those 14 types into 4, saying “Today I want to review four categories of financial aid,” most would find the thesis far less overwhelming.

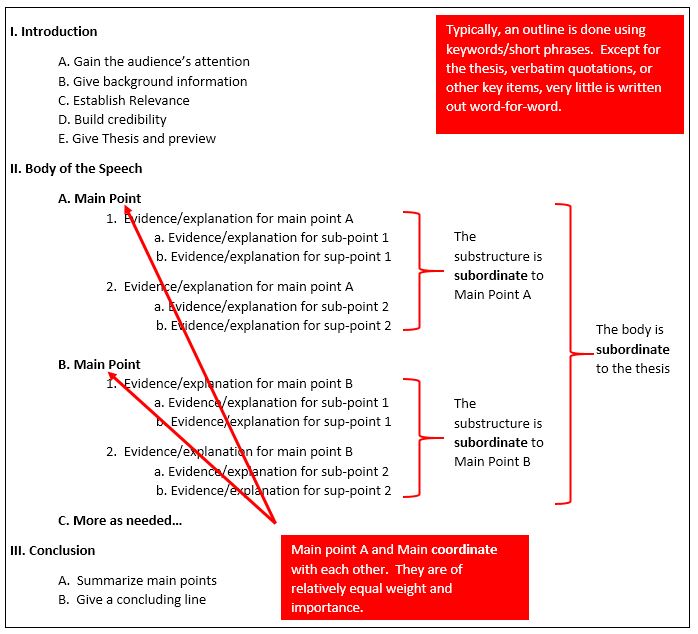

Coordination and Subordination

Main points have two key issues. First, the main points are coordinate with each other. The main points are of relatively equal importance, justifying them being set off as separate points. Second, each main point is part of the thesis, and once they are addressed, they fulfill the thesis. The main points are subordinate to the thesis; they fit within it and are part of it.

This image is a generic sample of an outline demonstrating coordination and subordination. There are many different formats for outlines, so be aware that specific expectations for instructors will vary.

Organizing the Main Points

When developing the speech, an important step is to decide the order in which to present the main points. Speakers need to remember although they will have a thorough understanding of the content, they need to stop and think what will work well with the given audience. Just because the speaker is well versed in the information does not mean the audience will understand it clearly, unless the speaker presents it in a well-planned structure based on the audience’s needs.

Clear organization is important for three reasons:

- It makes the information much more memorable for the audience. To remember information, we need it organized, and it is up to the speaker to provide the organization.

- It reduces the chance of the audience getting lost or confused. Once they are lost, it is very hard to get the audience back on track. Creating confusion is easy; reducing confusion is difficult.

- A well-organized speech is easier for the speaker to better recall the order of the ideas to be presented.

In ordering the main points, use a logical idea development pathway. The speaker considers which order of presentation will be most effective with the audience in leading them to an understanding of the material. There are no concrete rules about what does/does not work because it depends on the topic and audience, but there are some common ways to do this:

- Present the information chronologically. For a process speech, take us through it in time-order, e.g., first step, second step, etc.

- Present the information spatially. In describing a place, take us through it by location. For example, if describing vacation opportunities in Minnesota, dividing the state into southern, central, and northern Minnesota provides structure to the information.

- Present the information topically. Divide the speech into major subtopics, and order them in a logical pattern. Start from specific and go broad, or start broad and move to specifics. To inform about financial aid, perhaps start with the most common to the least common. Or for a speech on iPads, the speaker might begin with what an iPad is and how it developed, then on to the ways students are using them, and then look at some unique and different ways iPads are being employed.

- Use a problem/solution format. Show us the problem being addressed, and then lay out the solution that is being used or advocated. The problem/solution format is commonly used in persuasion. For example, if a student wants to argue that college textbook prices are too high, they might first explain why they are expensive, then offer an alternative to using traditional bookstore texts. The format can also be used for informative speaking if the purpose of the speech is to discuss a problem and how it was solved, not advocating a solution, just telling us about what others did.

- Use a cause/effect format. For speeches attempting to show two things are linked causally, tell us about the causes and the impacts of those causes. This can be used in either informative or persuasive speaking. For example, a speaker could inform an audience on how caffeine affects memory by discussing how caffeine works chemically and then how it interacts with the body. For a persuasive speech, the speaker could attempt to persuade the audience that artificial sweeteners are bad for a person using the same structure; talk about how they work and how they impact the body.

Regardless of how the speaker orders the main point, the goal is always the same, move the audience along an idea development pathway that is logical, easy to follow, enhances memory value and understanding.

The Substructure

The substructure of the speech is the content included within each main point. The substructure contains the actual information, data, and arguments the speaker wishes to communicate to the audience. Within the substructure, the speaker must continue to determine the best order for items to be presented so the speaker and the audience can follow the development of ideas. This is the core of the speech. How to use evidence and sources will be addressed in a later sectionSee Module VIII, Section 4.

Incorporating Transitions

Transitions are a vital component of any good speech. Their role is to verbally move the audience from point to point, keep the audience on track, and to clearly lead the audience through the organization. It is important to have the audience on track from the start, and to keep them on track. If a reader gets lost, they can simply go back and re-read, but in speaking, if the audience gets lost, it can be very hard to get them back on track.

In public speaking, we like to use signpost transitions which are blatant transitions, such as “My second point is….” We are far less subtle in speaking than in writing.

There are five types of transitions we use in speaking:

- Thesis/Preview: This is a special transition used immediately after the thesis to preview the main points. Each point is briefly mentioned to let the audience know what is coming. For example,

- Single Words/phrases:The Purdue Online Writing Center lists several categories of transitional terms that can be used to guide your audience through the speech. These are general transition terms used throughout the speech, but mainly in the substructure. These include terms and phrases such as “also,” “in addition to,” “furthermore,” “another,” and so on.

- Numerical terms: Numbering is a common and very effective way to aid an audience in keeping track of a series of points. Terms such as “first,” “second,” and “third,” can be very effective in clearly identifying major points. The major danger with these is their overuse. If a speaker uses numerical terms as transitions between main points, then uses them again in the substructure, the audience is likely to get confused.

- Parallel Structure: Parallel structure is mainly used as main point transitions. The main point statements are worded very similarly. Once the audience hears the similarly worded statements, they know they are moving into a new topic. For example, referring to the earlier example, the three main points could be worded as:

- Summary/Preview: Summary/Preview transitions are an excellent choice for moving between main points. At the end of the main point, the speaker says one sentence in which the first half summarizes what was just covered, and the second half previews what is coming up. For example, “Now that we have looked at special scholarships, we can move on and consider reimbursements you can get from your workplace.” This is a very distinct, clean, and effective transition. Also, by stating the focus of the next main point, the speaker can now move directly into the sub-structure of the main point.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Writing a speech versus Developing a speech

Incorporating Evidence

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- explain how using support materials impacts speaker credibility.

- differentiate between internal and external evidence.

- distinguish the three types of testimony.

- distinguish the three types of examples.

- differentiate between descriptive and inferential statistics.

- cite a source appropriately.

- judge the validity of a source.

Once we have a good idea of what we want to say in the speech, we need to find and include support materials. Support materials refer to any type of evidence, explanation, or illustration we use in the speech to enhance the likelihood the audience will accept and believe what we say.

Credibility

We use support materials because we need to enhance the credibility, the believability, of our message with the audience. Our audiences will only believe our messages if they can have faith that what we are saying is reflective of the truth or the best ideas. Audiences should believe in us as speakers and in our message. The use of support materials builds our credibility and the credibility of our message.

In today’s political climate, the ability to identify quality evidence is extremely important. With claims of “fake news” being used to dismiss any information not meeting one’s pre-existing beliefs, our ethical obligation to identify the very best sources of information is greater than ever. Compounding this challenge is the plethora of web sites established to advocate certain viewpoints, to cherry-pick news stories for the most sensational tidbits, or to outright fabricate news stories. More than ever we must be critical consumers of information, carefully assessing what we are reading and hearing to separate truth from fiction, and reality from sensationalism. As speakers, we must use that same critial process to insure we are presenting evidence to our audience that can withstand scrutiny. To that end, later in this section, we present the CRAAP test for evaluating sources.

When using evidence, especially from outside our own experiences, we rely on credibility transfer. We select good, quality sources we anticipate the audience will find credible, with the hope that by using that source, the credibility attributed to the source will transfer to us as speakers. That is why good, clear source citations are so important. By citing the source, we are giving information to the audience to allow them to establish the credibility of the source and to enhance our credibility as the speaker.

There are two broad categories of evidence: internal and external. Internal evidence refers to our own personal experiences, knowledge and opinions. The evidence can be strong if the audience sees us as having expertise in the area. As the audience’s perception of the speaker’s credibility increases, the speaker can rely more on internal evidence and less on external. However, even highly credible speakers will still use external evidence as well to enhance their expertise.

External evidence is the experiences, information and opinion from someone other than the speaker. For external evidence to carry weight with the audience, they must view these external sources as credible.

Types of External Evidence

There are three types of evidence: testimony, examples, and statistics. Each one has its strengths and weaknesses.

Testimony

Testimony refers to quotations by others about the topic. When quoting someone, we can either quote verbatim, or we can paraphrase. When quoting verbatim, the speaker is quoting the person exactly as the person said it. This works well if the quotation is worded in a very powerful, memorable, impactful manner. Paraphrasing is restating what the source said in the speaker’s own words, but keeping the intent of what was said. Paraphrasing is especially valuable when dealing with longer quotations, or with quotations in which the wording is confusing or not as engaging as the speaker wants. Regardless of why the information is paraphrased, the speaker has an ethical obligation to make sure the quotation is translated in a manner keeping the intent of the original.

There are three types of testimony: lay, prestige, and expert.

- Lay testimony refers to statements by the “person on the street.” These can be effective as audience members may relate more to “someone like me.” Infomercials use lay testimony heavily to try to prove the advertised product will work for “someone just like you.” It is important to remember a lay person is not an expert, so the proof value may not be as high as the speaker assumes.

- Prestige testimony is from someone who is well known, but is not considered an expert in their field. Examples would include statements by celebrities like John Stewart, Stephen Colbert, or from the world of movies, television, or literature. They are usually used because of their interesting, engaging nature, although their ability to seriously prove a point is not strong. These are virtually always quoted verbatim.

- Expert testimony is from someone who is an expert in the topic. These quotations carry the most weight of the three types of testimony ifthe audience sees this person as being highly credible. Expert testimonies are usually found in newspapers, magazines, journals, or off internet research sites. Their weakness is often the wording can be dry and “academic” in tone, so frequently the speaker will need to paraphrase the quotation to have it carry more “punch” with the audience.

Examples

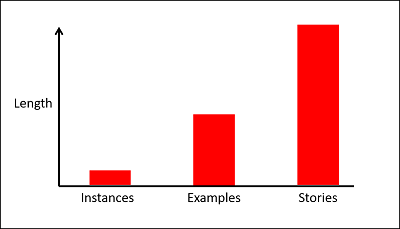

Examples are narratives relating to the topic. They can range from instances to examples to stories, depending on length.

An instance is a quick reference, usually in a word or two, about a specific occurrence. For example, “D-Day” would remind the audience of a larger specific event, or “9/11” would remind the audience of the attacks on the World Trade Centers. Be sure the audience understands the reference. For example, for many people today, making a reference to “Columbine” may not be as effective as it was a few years ago.

On the other end of the continuum are stories. Stories are fully developed narratives with a beginning, middle, and end. They can be used for longer speeches, but are usually too involved for shorter speeches. The advantage of stories, if given well, they can be very involving and interesting. If they are not told well, they can end up being boring. The keys to using stories effectively are that the speaker tells the story well, and the story has a point that adds significantly to the purpose of the speech.

On the other end of the continuum are stories. Stories are fully developed narratives with a beginning, middle, and end. They can be used for longer speeches, but are usually too involved for shorter speeches. The advantage of stories, if given well, they can be very involving and interesting. If they are not told well, they can end up being boring. The keys to using stories effectively are that the speaker tells the story well, and the story has a point that adds significantly to the purpose of the speech.

In the middle is the more common example. When using an example, the speaker gives the pertinent details, but does not develop it as a full-blown story. For example, to illustrate a speech on drinking and driving, a speaker might give some examples of individuals who were injured and the long-lasting effects. Saying only the name of the victim would not work, nor would the speaker want to tell the whole story of each person. The speaker gives the important details of each example, enough so the audience understands the point of the example.

Generally, examples are a very effective form of proof with an audience, although by themselves they do not often prove the breadth of the problem; after all, one or two examples do not prove there is a widespread problem. However, due to the human interest we experience with examples, they have the ability, when well delivered, to involve the audience more on a human, emotional level than on a rational, cognitive level.

Statistics

Statistics refer to the numerical representation of data. Statistics can be the most powerful form of evidence to prove the extent of a problem; however, they can also be horrendously misused. In western culture, we tend to believe once a problem has been quantified and expressed in statistics, the statistics are inherently truthful. Statistics can be manipulated, misused, and misrepresented just as any other evidence can be misused. Speakers must be especially cautious when selecting statistics to be sure the numbers come from a quality source and are accurate reflections of reality.

Statistics are used in two ways: descriptively and inferentially. Descriptive statistics describe what was true at a given moment in time. They describe data from the past. The past can be distant, such as in years, or recent, such as hours or days. The statistics reflect what was found when the statistics were gathered. For example, if a poll is taken on a Monday to determine which of two candidates is ahead in a political race, the statistics reflect what was found on the day. If on Wednesday, the media reports one candidate was arrested for drug dealing 10 years earlier, the results of Monday’s poll become worthless as they reflected the results prior to the revelation of the drug dealing. When asked what the enrollment of Ridgewater College is, we usually refer to what is called “10th day enrollment.” The enrollment of Ridgewater on the 10th day of the semester is used as the official attendance figure, but since students tend to drop out throughout the semester even on the 11th day the number may be wrong. Descriptive statistics report what was found on the day at the time. Descriptive statistics are the type we encounter most of the time.

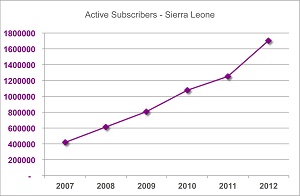

Inferential statistics are used to predict what may happen in the future. Simply taking descriptive statistics and assuming what they report will be true in the future is a faulty assumption. Rather, inferential statistics are specifically developed to predict behavior. For example, if a study establishes through valid research that as the poverty rate increases crime increases, we could infer if a community experiences a rise in the poverty rate, they are likely to experience a rise in the crime rate. The statistics link behaviors together. Physicians use statistics inferentially daily. As medications are tested, statistical relationships between variables, such as weight, and therapeutic effect are determined. Doctors then use the statistics to determine the appropriate dosage for a given patient, predicting with a high degree of confidence the medical outcome.

Whether used descriptively or inferentially, statistics have some distinct issues:

- The Source: Hundreds of organizations in the U.S. have the goal of persuading the American people and American government to a specific position. Since their goal is inherently biased to one position, statistics released by the organizations are inherently biased. Even if the statistics they release were gathered and processed properly, they will be selective in which statistics they release, publishing only ones supporting their position.

- Gathering/Processing: Gathering and processing statistics have distinct guidelines. If statistics are not gathered using the guidelines, the quality of the statistics is highly questionable. Get statistics from reliable sources to produce quality statistical data.

- Interpretation: It is important speakers use statistics honestly, not inferring conclusions from them the statistics may not support. For example, if a speaker has statistics that 60% of Americans favor hand gun control, they should not use those to claim that the majority of Americans favor gun control; the statistics are specific to hand gun control, not gun control in general.

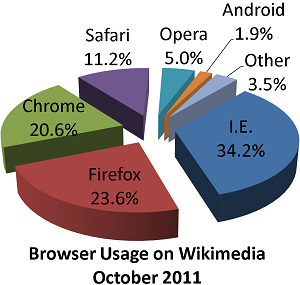

- Presentation: Statistics can be very confusing. The use of graphs helps immensely in clarifying numbers. It is up to the speaker to make sure the audience understands what the statistics are saying.

Evaluating Sources

Regardless of the type of evidence used, a core ethical speaker responsibility is presenting the audience with quality, trustworthy information. One way to do this is apply the CRAAP Test to sources. Adapted from “Evaluating Information—Applying the CRAAP Test, “ from the Meriam Library of California Sate University, Chico, there are five criteria to apply to when evaluating sources:

Currency: The timeliness of the information.

- When was the information published or posted?

- Has the information been revised or updated?

- Does the topic require current information, or will older sources work as well?

- Are the links functional?

Relevance: The importance of the information for the speech.

- Does the information relate to the specific purpose of the speech?

- Who is the intended audience for the information?

- Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e. not too elementary or advanced for the needs)?

- Is this the best of several sources reviewed?

- Will providing this information from this source increase the likelihood that the audience will accept the speech content as valid and credible?

Authority: The source of the information.

- Who is the author/publisher/source/sponsor?

- What are the author’s credentials or organizational affiliations?

- Is the author qualified to write on the topic?

- Is there contact information, such as a publisher or email address?

- Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source? Examples: .com .edu .gov .org .net

- Will this source be viewed as credible by the audience?

Accuracy: The reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content.

- Where does the information come from?

- Is the information supported by evidence?

- Has the information been reviewed or refereed?

- Can the information be verified in another source or from personal knowledge?

- Does the language or tone seem unbiased and free of emotion?

- Are there spelling, grammar or typographical errors?

- Can the accuracy of this source be easily defended?

Purpose: The reason the information exists.

- What is the purpose of the information? Is it to inform, teach, sell, entertain or persuade?

- Do the authors/sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear?

- Is the information fact, opinion or propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

- Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional or personal biases?

Source Citations

Whenever a speaker uses any external sources, a source citation must be given. One major reason is to avoid plagiarism, presenting others’ ideas and words as one’s own. Citing sources also facilitates the credibility transfer process discussed earlier. If the speaker does not cite the sources, the audience will not know the sources were used; hence, the credibility transfer process will not occur.

In a speech, sources are cited differently than in writing. Obviously, we cannot use footnotes or give a list of works cited at the end of our speech. Instead, the speaker should verbally cite the sources where they are used.

Speakers can be creative and vary how the source is cited and when it is cited. They should be cited smoothly, fitting into the overall flow of the speech. When citing the source, give enough information an audience member could reasonably locate the source and the audience can make a determination of credibility.

Here are some examples of typical source citations:

- “According to the May 3, 2009, Star Tribune article by Dr. Amy Fisher…”

- “Dr. Dana Brown, Director of the Breast Cancer Research Fund, said in last week’s Time magazine, that…”

- “John Gray, in his 1992 book, Men are From Mars, Women are From Venus, explained…”

- “Just last month in Esquire magazine, Stephen Colbert said…”

They are more casual and succinct than citations in a research paper would be. Some instructors require students to hand in a typed bibliography and will usually want it in either MLA or APA format. Students should pay attention to their instructor’s expectations.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Types of External Evidence

References

Meriam Library, California State University, Chico. (2010). Evaluating Information—Applying the CRAAP Test. Retrieved from https://www.csuchico.edu/lins/handouts/eval_websites.pdf

Introductions and Conclusions

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- use the Primacy-Recency Effect to explain the importance of introductions and conclusions.

- construct an introduction fulfilling the purposes of an introduction.

- select, develop, and use an attention-getting device.

- identify methods to build speaker credibility.

- employ methods to enhance speaker and topic relevance.

- develop a summary of the speech.

- employ a concluding method to end a speech.

Introductions

Regardless of how well developed the body of the speechSee Module VIII, Section 5. is, the speaker has to be able to grab and keep the audience’s interest. The speaker gets them to want to listen. How well a speaker starts and ends the speech will significantly affect how the audience attends to the message and remembers the message.

The Primacy-Recency Effect

A phenomenon called the primacy-recency effect is a theory that argues we are most struck by and retain as most memorable the first and last things we experience about a situation, person, or event. Primacy refers to the first things we experience. We know first impressions are powerful and long lasting. They are our primary experiences with others, and set an overall tone for what to expect from this person in later interactions. Since we are so strongly driven to make sense of the world around us, once we make an initial assessment of what a person is like, it is very hard to change those initial perceptions. In public speaking, the introduction is the primary, initial encounter with the speaker. The audience quickly forms powerful first impressions of the speaker and the speech itself.

We know from our understanding of perceptionSee Module II, Section 2. that if our initial impression of something is positive, we then expect the subsequent experiences to likewise be positive. So if the introduction is strong, establishing a positive initial impression, the audience will assume the rest of the speech will be good. Since we are driven to find evidence affirming our expectations, the audience will tend to focus on the positive, minimizing the negative. The reverse is also true; if the beginning of the speech is poor, we then expect a poor speech, and we tend to highlight the speaker’s mistakes to prove our assumption to be true.