18 Javanotes 9.0, Section 6.6 — Complete Programs

Section 6.6

Complete Programs

In this chapter, we have covered many of the

basic aspects of GUI programming. There is still a lot more to learn,

and we will return to the topic in Chapter 13. But you

already know enough to write some interesting programs. In this

section, we look at two complete programs that use what you have

learned about GUI programming in this chapter, as well as what you

learned about programming in general in earlier chapters. Along

the way, we will also encounter a few new ideas.

6.6.1 A Little Card Game

The first program that we will consider is a GUI version

of the command-line card game HighLow.java

from Subsection 5.4.3. In the new version,

HighLowGUI.java, you look at a playing card and try to

predict whether the next card will be higher or lower in value. (Aces have the

lowest value in this game.) In this GUI version of the program,

you click on a button to make your

prediction. If you predict wrong, you lose. If you make three correct

predictions, you win. After completing a game, you can click “New Game”

to start another game. Here is

what the program looks like in the middle of a game:

The complete source code for the program can be found in the file

HighLowGUI.java. I encourage you to compile and run it.

Note that the program also requires Card.java, Deck.java,

and Hand.java, from Section 5.4,

since they define classes that are used in the program. And it requires

the file of card images, cards.png, that was used

in RandomCards.java from Subsection 6.2.4.

The layout of the program should be easy to guess:

HighLowGUI uses a BorderPane as the root

of the scene graph. The center position is occupied by a Canvas

on which the cards and a message are drawn. The bottom position contains an

HBox that in turn contains three Buttons.

In order to make the buttons fill the HBox, I set them

all to have the same width, as discussed in Subsection 6.5.3.

You can see all this in the start() method from the program:

public void start(Stage stage) {

cardImages = new Image("cards.png"); // Load card images.

board = new Canvas(4*99 + 20, 123 + 80); // Space for 4 cards.

Button higher = new Button("Higher"); // Create the buttons, and

higher.setOnAction( e -> doHigher() ); // install event handlers.

Button lower = new Button("Lower");

lower.setOnAction( e -> doLower() );

Button newGame = new Button("New Game");

newGame.setOnAction( e -> doNewGame() );

HBox buttonBar = new HBox( higher, lower, newGame );

higher.setPrefWidth(board.getWidth()/3.0); // Make each button fill

lower.setPrefWidth(board.getWidth()/3.0); // 1/3 of the width.

newGame.setPrefWidth(board.getWidth()/3.0);

BorderPane root = new BorderPane(); // Create the scene graph root node.

root.setCenter(board);

root.setBottom(buttonBar);

doNewGame(); // set up for the first game

Scene scene = new Scene(root); // Finish setting up the scene and stage.

stage.setScene(scene);

stage.setTitle("High/Low Game");

stage.setResizable(false);

stage.show();

} // end start()

Note that the event handlers call methods such as

doNewGame() that are defined elsewhere in the program.

The programming of those methods

is a nice example of thinking in terms of a state machine. (See Subsection 6.3.6.)

It is important to think in terms of the states that the game can be in, how the

state can change, and how the response to events can depend on the state. The

approach that produced the original, text-oriented game in

Subsection 5.4.3 is not appropriate here. Trying to think about

the game in terms of a process that goes step-by-step from beginning to end is

more likely to confuse you than to help you.

The state of the game includes the cards and the message. The cards are

stored in an object of type Hand.

The message is a String.

These values are stored in instance variables. There is also another, less

obvious aspect of the state: Sometimes a game is in progress, and the user is

supposed to make a prediction about the next card. Sometimes we are between

games, and the user is supposed to click the “New Game” button. It’s a good

idea to keep track of this basic difference in state. The program uses a

boolean instance variable named gameInProgress for this purpose.

The state of the game can change whenever the user clicks on a button. The

program has three methods to respond to button clicks:

doHigher(), doLower(), and newGame().

It’s in these three event-handling methods that the action of the game takes place.

We don’t want to let the user start a new game if a game is currently in

progress. That would be cheating. So, the response in the newGame()

method is different depending on whether the state variable

gameInProgress is true or false. If a game is in progress, the

message instance variable should be set to be an error message. If a

game is not in progress, then all the state variables should be set to

appropriate values for the beginning of a new game. In any case, the board must

be redrawn so that the user can see that the state has changed. The complete

newGame() method is as follows:

/**

* Called by the start() method, and called by an event handler if

* the user clicks the "New Game" button. Start a new game.

*/

private void doNewGame() {

if (gameInProgress) {

// If the current game is not over, it is an error to try

// to start a new game.

message = "You still have to finish this game!";

drawBoard();

return;

}

deck = new Deck(); // Create the deck and hand to use for this game.

hand = new Hand();

deck.shuffle();

hand.addCard( deck.dealCard() ); // Deal the first card into the hand.

message = "Is the next card higher or lower?";

gameInProgress = true;

drawBoard();

} // end doNewGame()

The doHigher() and doLower() methods are almost identical

to each other (and could probably have been combined into one method with a

parameter, if I were more clever). Let’s look at the doHigher()

routine. This is called when the user clicks the “Higher” button. This only

makes sense if a game is in progress, so the first thing doHigher()

should do is check the value of the state variable gameInProgress. If

the value is false, then doHigher() should just set up an

error message. If a game is in progress, a new card should be added to the hand

and the user’s prediction should be tested. The user might win or lose at this

time. If so, the value of the state variable gameInProgress must be

set to false because the game is over. In any case, the board is

redrawn to show the new state. Here is the doHigher() method:

/**

* Called by an event handler when user clicks "Higher" button.

* Check the user's prediction. Game ends if user guessed

* wrong or if the user has made three correct predictions.

*/

private void doHigher() {

if (gameInProgress == false) {

// If the game has ended, it was an error to click "Higher",

// So set up an error message and abort processing.

message = "Click \"New Game\" to start a new game!";

drawBoard();

return;

}

hand.addCard( deck.dealCard() ); // Deal a card to the hand.

int cardCt = hand.getCardCount();

Card thisCard = hand.getCard( cardCt - 1 ); // Card just dealt.

Card prevCard = hand.getCard( cardCt - 2 ); // The previous card.

if ( thisCard.getValue() < prevCard.getValue() ) {

gameInProgress = false;

message = "Too bad! You lose.";

}

else if ( thisCard.getValue() == prevCard.getValue() ) {

gameInProgress = false;

message = "Too bad! You lose on ties.";

}

else if ( cardCt == 4) {

gameInProgress = false;

message = "You win! You made three correct guesses.";

}

else {

message = "Got it right! Try for " + cardCt + ".";

}

drawBoard();

} // end doHigher()

The drawBoard() method, which is responsible for drawing the content

of the canvas, uses the values in the state variables to decide what to show. It displays the

string stored in the message variable. It draws each of the cards in

the hand. There is one little tricky bit: If a game is in progress, it

draws an extra face-down card, which is not in the hand, to represent the next

card in the deck. The technique for drawing the individual cards was

explained in Section 6.2. See the source code

for the method definition.

6.6.2 Menus and Menubars

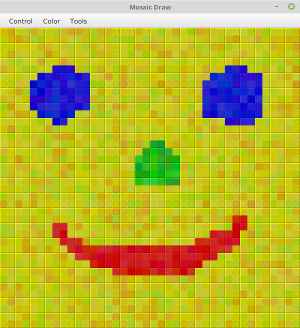

Our second example program, “MosaicDraw,” is a kind of drawing program.

The source code for the program is in the file MosaicDraw.java.

The program also requires MosaicCanvas.java. Here is a half-size

screenshot showing a sample drawing made with the program:

As the user clicks-and-drags the

mouse in the large drawing area of this program, it leaves a trail of little colored

squares. There is some random variation in the color of the squares. (This is meant

to make the picture look a little more like a real mosaic, which is a picture made out of

small colored stones in which there would be some natural color variation.) The program has

one feature that we have not encountered before:

There is a menu bar above the drawing area. The “Control” menu contains

commands for filling and clearing the drawing area, along with a few options that affect

the appearance of the picture. The “Color” menu lets the user select the color that will

be used when the user draws. The “Tools” menu affects the behavior of the mouse.

Using the default “Draw” tool, the mouse leaves a trail of single squares. Using the

“Draw 3×3” tool, the mouse leaves a swatch of colored squares that is three squares wide.

There are also “Erase” tools, which let the user set squares back to their default

black color.

The drawing area of the program is a panel that belongs to the MosaicCanvas

class, a subclass of Canvas that is defined in MosaicCanvas.java.

MosaicCanvas is a highly reusable class for representing mosaics of colored

rectangles. It was also used behind the scenes in the sample program in Subsection 4.7.3.

The MosaicCanvas class

does not directly support drawing on the mosaic, but it does support setting

the color of each individual square. The MosaicDraw program installs mouse handlers on

the canvas. The handlers respond to MousePressed and MouseDragged events on the

canvas by applying the currently selected tool to the canvas at the square

that contains the mouse position. This is a nice example of

applying event listeners to an object to do something that was not programmed into the object

itself.

I urge you to study MosaicDraw.java. I will not be discussing all aspects

of the code here, but you should be able to understand it all after reading this section. As for

MosaicCanvas.java, it uses some techniques that you would not understand at this

point, but I encourage you to at least read the comments in that file to learn about the API

for MosaicCanvas.

MosaicDraw is the first example that we have seen that uses a menu bar. Fortunately,

menus are very easy to use in JavaFX. The items in a menu are represented by objects belonging

to class MenuItem or to one of its subclasses.

(MenuItem and other menu-related classes are in package javafx.scene.control.)

Menu items are used in almost exactly the

same way as buttons. In particular, a MenuItem can be created using

a constructor that specifies the text of the menu item, such as:

MenuItem fillCommand = new MenuItem("Fill");

Menu items, like buttons, can have a graphic as well as text, and there is a second

constructor that allows you to specify both text and graphic.

When the user selects a MenuItem from a menu, an ActionEvent

is generated. Just as for a button, you can add an action event listener to the menu item using its

setOnAction(handler) method. A menu item has a setDisable(disabled) method

that can be used to enable and disable the item. And it has a setText() method for

changing the text that is displayed in the item.

The main difference between a menu item and a button, of course, is that a menu

item is meant to appear in a menu. (Actually, a menu item is a Node

that can appear anywhere in a scene graph, but the usual place for it is in a menu.)

A menu in JavaFX is

represented by the class Menu. (In fact, Menu

is actually a subclass of MenuItem, which means that you can

add a menu as an item in another menu. The menu that you add becomes a submenu of the

menu that you add it to.) A Menu has a name,

which is specified in the constructor. It has an instance method getItems()

that returns a list of menu items contained in the menu. To add items to the

menu, you need to add them to that list:

Menu sampleMenu = new Menu("Sample");

sampleMenu.getItems().add( menuItem ); // Add one menu item to the menu.

sampleMenu.getItems().addAll( item1, item2, item3 ); // Add multiple items.

Once a menu has been created, it can be added to a menu bar. A menu bar is represented

by the class MenuBar. A menu bar is just a container for menus.

It does not have a name. The MenuBar constructor can be called

with no parameters, or it can have a parameter list containing Menus

to be added to the menu bar. The instance method getMenus()

returns a list of menus, with methods add() and addAll()

for adding menus to the menu bar. For example,

the MosaicDraw program uses three menus, controlMenu, colorMenu,

and toolMenu. We could create a menu bar and add the menus to it with

the statements:

MenuBar menuBar = new MenuBar(); menuBar.getMenus().addAll(controlMenu, colorMenu, toolMenu);

Or we could list the menus in the menu bar constructor:

MenuBar menuBar = new MenuBar(controlMenu, colorMenu, toolMenu);

The final step in using menus is to add the menu bar to the program’s

scene graph. The menu bar could actually appear anywhere, but typically,

it should be at the top of the window. A program that has a menu bar

will usually use a BorderPane as the root of

its scene graph, and it will add the menu bar as the top component

in that root pane. The rest of the GUI for the program can be placed

in the other four positions of the border pane.

So using menus generally follows the same pattern: Create a menu bar. Create menus

and add them to the menu bar. Create menu items and add them to the menus (and set up

listening to handle action events from the menu items). Place the menu bar at the

top of a BorderPane, which is the root of the scene graph.

There are other kinds of menu items, defined by subclasses of MenuItem,

that can be added to menus. A very simple example is SeparatorMenuItem,

which appears in a menu as a line between other menu items. You can see an example

in the “Control” menu of MosaicDraw. To add a separator to

a Menu, menu, you just need to say

menu.getItems().add( new SeparatorMenuItem() );

Much more interesting are the subclasses CheckMenuItem

and RadioMenuItem.

A CheckMenuItem represents a menu item that can be in one

of two states, selected or not selected. The state is changed when the user

selects the item from the menu that contains it.

A CheckMenuItem has the same functionality and is used in

the same way as a CheckBox (see Subsection 6.4.3).

Three CheckMenuItems are used in the “Control” menu

of the MosaicDraw program. One is used to turn the random color variation of

the squares on and off. Another turns a symmetry feature on and off; when symmetry is

turned on, the user’s drawing is reflected horizontally and vertically to produce

a symmetric pattern. And the third CheckMenuItem shows and hides

“grouting” in the mosaic (grouting consists of gray lines drawn around each

of the little squares in the mosaic). The CheckMenuItem that corresponds to the

“Use Randomness” option in the “Control” menu could be set up with the statements:

useRandomness = new CheckMenuItem("Use Randomness");

useRandomness.setSelected(true); // Randomness is initially turned on.

controlMenu.getMenus().add(useRandomness); // Add menu item to the menu.

No ActionEvent handler is added to useRandomness;

the program simply checks its state by calling useRandomness.isSelected()

whenever it is coloring a square, to decide whether to

add some random variation to the color. On the other hand, when the user selects the

“Use Grouting” check box from the menu, the canvas must immediately be redrawn to

reflect the new state. A handler is added to the CheckMenuItem

to take care of that by calling an appropriate method:

useGrouting.setOnAction( e -> doUseGrouting(useGrouting.isSelected()) );

The “Color” and “Tools” menus contain items of type RadioMenuItem,

which are used in the same way as the RadioButtons that were

discussed in Subsection 6.4.3: A RadioMenuItem,

like a check box, can be either selected or unselected, but when several

RadioMenuItems are added to a ToggleGroup,

then at most one of the group members can be selected. In the program, the user

selects the tool that they want to use from the “Tools” menu. Only one

tool can be selected at a time, so it makes sense to use RadioMenuItems

to represent the available tools, and to put all of those items into the same

ToggleGroup. The currently selected option in the “Tools” menu will be

marked as selected; when the user chooses a new tool, the mark is moved. This gives the

user some visible feedback about which tool is currently selected for use.

Furthermore, the ToggleGroup has an observable property

representing the currently selected option (see Subsection 6.3.7). The program

adds a listener to that property with an event handler that will be

called whenever the user selects a new tool. Here is the code that creates the

“Tools” menu:

Menu toolMenu = new Menu("Tools");

ToggleGroup toolGroup = new ToggleGroup();

toolGroup.selectedToggleProperty().addListener(

e -> doToolChoice(toolGroup.getSelectedToggle()) );

addRadioMenuItem(toolMenu,"Draw",toolGroup, true);

addRadioMenuItem(toolMenu,"Erase",toolGroup, false);

addRadioMenuItem(toolMenu,"Draw 3x3",toolGroup, false);

addRadioMenuItem(toolMenu,"Erase 3x3",toolGroup, false);

The addRadioMenuItem method that is used in this code

is a utility method that is defined elsewhere in the program:

/**

* Utility method to create a radio menu item, add it

* to a ToggleGroup, and add it to a menu.

*/

private void addRadioMenuItem(Menu menu, String command,

ToggleGroup group, boolean selected) {

RadioMenuItem menuItem = new RadioMenuItem(command);

menuItem.setToggleGroup(group);

menu.getItems().add(menuItem);

if (selected) {

menuItem.setSelected(true);

}

}

The complete code for creating the menu bar in MosaicDraw can

be found in a method createMenuBar(). Again, I encourage you

to study the source code.

6.6.3 Scene and Stage

Before ending this brief introduction to GUI programming,

we look at two fundamental classes in a little more detail:

Scene, from package javafx.scene,

and Stage, from package javafx.stage.

A Scene represents the content area of a window

(that is, not including the window’s border and title bar),

and it serves as a holder for the root of the scene graph.

The Scene class has several constructors, but they

all require the root of the scene graph as one of the parameters, and the

root cannot be null. Perhaps the most common constructor is

the one that has only the root as parameter: new Scene(root).

A scene has a width and a height, which can be specified as parameters to the

constructor: new Scene(root,width,height). In the typical case

where the root is a Pane, the size of the

pane will be set to match the size of the scene, and the pane will lay out

its contents based on that size. If the size of the scene is not specified in the constructor,

then the size of the scene will be set to the preferred size of the pane.

It is not possible for a program to set the width or

height of a Scene after it has been created, but if the size of the stage that

contains a scene is changed, then the size of the scene is automatically changed

to match the new size of the stage’s content area, and the root node of the

scene (if it is a Pane) will be resized as well.

A Scene can have a background fill color (actually

a Paint), which can be specified in the constructor. Generally, the scene’s

background is not seen, since it is covered by the background of the root node. The default

style sets the background of the root to be light gray. However, you can set the background color

of the root to be transparent if you want to see the scene background instead.

A Stage, from package javafx.stage, represents a

window on the computer’s screen. Any JavaFX Application has at

least one stage, called the primary stage, which is created by the system and passed

as a parameter to the application’s start() method. Although we have not seen any

examples so far in this textbook, many programs

use more than one window. It is possible for a program to create new Stage

objects; we will see how to do that in Chapter 13.

A stage contains a scene, which fills its content area. The scene is installed in the stage by calling the

instance method stage.setScene(scene). It is possible to show a stage

that does not contain a scene, but its content area will just be a blank rectangle.

In addition to a content area, a stage has a title bar above the content. The title bar

contains a title for the window and some “decorations”—little controls that the

user can click to do things like close and maximize the window. The title bar is provided

by the operating system, not by Java, and its style is set by the operating system.

The instance method stage.setTitle(string) sets the text that is shown in

the title bar. The title can be changed at any time.

By default a stage is resizable. That is, the size of the window can be changed by the

user, by dragging its borders or corners. To prevent the user from changing the

window size, you can call stage.setResizable(false). However, a program

can change the size of a stage with the instance methods stage.setWidth(w)

and stage.setHeight(h), and this can be done even if the stage has

been made non-resizable. Usually, the initial size of a stage is determined by the

size of the scene that it contains, but it is also possible to set the initial size before

showing the window using setWidth() and setHeight().

By default, when a stage is resizable, the user can make the window arbitrarily small

and arbitrarily large. It is possible to put limits on the resizability of a window

with the instance methods stage.setMinWidth(w), stage.setMaxWidth(w),

stage.setMinHeight(h), and stage.setMaxHeight(h). The size

limits apply only to what the user can do by dragging the borders or corners of the window.

It is also possible to change the position of a stage on the screen, using the

instance methods stage.setX(x) and stage.setY(y).

The x and y coordinates specify the position of the top left corner of the window,

in the coordinate system of the screen. Typically, you would do this before showing

the stage.

Finally, for now, remember that a stage is not visible on the screen until you

show it by calling the instance method stage.show(). Showing the

primary stage is typically the last thing that you do in a application’s

start() method.

6.6.4 Creating Jar Files

Java classes and resource files are often distributed in jar (“java archive”) files.

For a program that consists of multiple files, it can make sense to pack them

into a single jar file. As the last topic for this chapter, we look at how to do that.

The program can be run directly from the jar file, without unpacking it. However, for

JavaFX programs, the user will still need access to the JavaFX SDK.

A jar file can be “executable,” meaning that it specifies the class that

contains the main() routine that will be run when the jar file is

executed. If you have an executable jar file that does not require JavaFX or

other external resources, you can run it on the command line using a command

of the form:

java -jar JarFileName.jar

and you might even be able to run the jar file by double-clicking its icon in

a file browser window. If an executable jar file requires JavaFX, you will need

to add the same options to the java command that were discussed in

Subsection 2.6.7. For example,

java -p /opt/jfx17/lib --add-modules=ALL-MODULE-PATH JarFileName.jar

The question, then, is how to create a jar file. The answer depends on what

programming environment you are using. The two basic types of programming environment—command line

and IDE—were discussed in Section 2.6. Any IDE (Integrated Development Environment)

for Java should have a command for creating jar files. In the Eclipse IDE, for example,

it can be done as follows: In the Package Explorer pane, select the programming project (or just

all the individual source and resource files that you want to include). Right-click on the selection, and

choose “Export” from the menu that pops up. In the window that appears, select “JAR file”

and click “Next”. In the window that appears next, enter a full path name for the jar file in

the box labeled “JAR file”. (Click the “Browse” button next to this box to select the

file name using a file dialog box.) The name of the file should end with “.jar”.

If you are creating a regular jar file, not an executable

one, you can hit “Finish” at this point, and the jar file will be created. To create an

executable file, hit the “Next” button twice to get to the “Jar Manifest

Specification” screen. At the bottom of this screen is an input box labeled “Main class”.

You have to enter the name of the class that contains the main() routine

that will be run when the jar file is executed. If you hit the “Browse” button next to

the “Main class” box, you can select the class from a list of classes that contain

main() routines. Once you’ve selected the main class, you can

click the “Finish” button to create the executable jar file.

It is also possible to create jar files on the command line. The Java Development Kit

includes a command-line program named jar that can be used to create jar files.

If all your classes are in the default package (like most of the examples in this book), then

the jar command is easy to use. To create a non-executable jar file on the command line,

change to the directory that contains the class files that you want to include in the jar.

Then give the command

jar -c -f JarFileName.jar *.class

where JarFileName can be any name that you want to use for the jar file.

The -c option is used to create a jar file. The -f is followed by

the name of the jar file that is to be created.

The “*” in “*.class” is a wildcard that makes *.class match every class

file in the current directory. This means that all the class files in the directory will be

included in the jar file. If you want to include only certain class files, you

can name them individually, separated by spaces. You can also list the class file names separately.

If the program uses resource files, such as images, they should

also be listed in the command. (Things get more complicated if your classes and resources are not in the

default package. In that case, the files must be in subdirectories of the

directory in which you issue the jar command, and you have to include the path to

the file in the name. For example: textio/TextIO.class on MacOS and Linux,

or textio\TextIO.class on Windows.)

Making an executable jar file on the command line is only a little more complicated.

There has to be some way of specifying which class contains the main()

routine. This can be done by adding the -e option to the command,

with a value giving the full name of the class that is to be executed when the

jar file is run. For example, if the name of the class is MyMainClass,

then the jar file could be created with:

jar -c -f JarFileName.jar -e MyMainClass *.class

For a program defined in two packages, grapher.ui and grapher.util,

with a main class defined in the file Main.java in package grapher.ui,

the command would become

jar -c -f Grapher.jar -e grapher.ui.Main grapher/ui/*.class grapher/util/*.class

except that on Windows, the slashes would be replaced by backslashes.

(The options -c, -f, and -e are abbreviations

for the longer forms –create, –file, and –main-class,

and you can use the longer forms, if you prefer clarity to brevity.)

6.6.5 jpackage

You can collect the class files and resource files for a program into a jar file,

and you can give that jar file to someone who would like to use your

program. However, that person will still need to have Java installed on their

computer—something that is really not very likely these days, unless that person

is a Java developer. A possible solution is to bundle a Java virtual machine

along with your program. The Java Development Kit includes the jpackage

command to make that possible.

The jpackage command can create an installer that will install your

program along with as much Java support as is needed to run it. It has some

significant limitations. It can only make an installer for the type of computer

and operating system that you are using; for example, it is not possible to use jpackage

on Linux to make an installer for Windows. And the files that it makes are very

large, since they have to include large parts of a Java execution environment.

So jpackage is really meant for packaging large, serious applications.

But if you want to try it, here is a basic example, using only a few of the

options that are available for jpackage. For the example,

I made an installer for the network poker game from Subsection 12.5.4.

This might also help you understand how to work with packages in general.

To apply jpackage to a program that uses JavaFX, you have to make

Java packages available to the jpackage command. For this purpose,

you can’t use the JavaFX SDK. Instead, you need the JavaFX “jmods”. See

Subsection 2.6.7 for a discussion of the JavaFX SDK. For jpackage,

you will need to download the jmods for your operating system from

https://gluonhq.com/products/javafx/.

For my computer, I extracted the downloaded file into /opt/javafx-jmods-17.0.2.

(The jmods are required because they include specific operating system support that is not in

the SDK jar files.)

To use jpackage, you need a jar file that contains the classes and resource files for your

program. The poker game uses classes from the packages netgame.common and

netgame.fivecarddraw, plus a resource image file cards.png

in netgame.fivecarddraw. To make the jar file, I first compiled

the Java files for the program. Since the poker game uses JavaFX, I included the

necessary options in the javac command.

I used the following command in the directory that contained

the netgame directory, typed all on one line:

javac --module-path /opt/jfx17/lib --add-modules=ALL-MODULE-PATH

netgame/common/*.java netgame/fivecarddraw/*.java

I then created a jar file, Poker.jar, with this command,

typed all on one line:

jar -c -f Poker.jar netgame/common/*.class netgame/fivecarddraw/*.class

netgame/fivecarddraw/cards.png

It is important to include the image resource file along with the class files.

(Note that on Windows, the slashes, “/”, would be replaced by backslashes, “\”.)

I moved Poker.jar to a new directory. Working in that new directory,

I used the following very long jpackage command, again typed all on one line:

jpackage --input . --main-jar Poker.jar

--main-class netgame.fivecarddraw.Main --name NetPoker

--module-path /opt/javafx-jmods-17.0.2

--add-modules javafx.base,javafx.controls,javafx.graphics

The value for the –input option is a period, which represents the current working

directory; it could be replaced by a path to the directory that contains Poker.jar.

The value for the –main-class option is the full name of the class that

contains the main program; this option is not needed if the jar file is executable.

The value of the –name option is used to name the installer and

to name the executable file that it will install. The –module-path

refers to the directory that contains the JavaFX jmods. And the added modules

are just those JavaFX modules that are needed for this program.

When used on my computer, running Linux Mint, this produced a file named

netpoker_1.0-1_amd64.deb that I could

then install in the usual way. It installed the poker executable

as /opt/netpoker/bin/NetPoker.

On MacOS 10.15, using the JDK from adoptium.net (see Subsection 2.6.1),

I found that jpackage was installed as part of the

JDK, but it was not made available on the command-line. I was able to define it

myself as an alias:

alias jpackage=

"/Library/Java/JavaVirtualMachines/temurin-17.jdk/Contents/Home/bin/jpackage"

Again, type this all on one line. With that done, I used the same commands

as given above, with appropriate directory names for the JavaFX SDK and jmods.

The result was a .dmg file containing a program, netpoker.app,

that could be run by double-clicking. (The jpackage command might be properly set up

in newer versions of MacOS.)

The jpackage command should also work on Windows, but it requires

something called the “WiX toolset” in addition to the JDK. I have not tried it.