68 Javanotes 9.0, Section 12.5 — Network Programming Example: A Networked Game Framework

Section 12.5

Network Programming Example: A Networked Game Framework

This section presents several programs that use

networking and threads. The common problem in each application is to support

network communication between several programs running on different computers.

A typical example of such an application is a networked game with two or

more players, but the same problem can come up in less frivolous applications

as well. The first part of this section describes a framework that

can be used for a variety of such applications, and the rest of the section

discusses three specific applications that use that framework. This is

a fairly complex example, probably the most complex

in this book. Understanding it is not essential for a basic understanding

of networking.

This section was inspired by a pair of students, Alexander Kittelberger and

Kieran Koehnlein, who wanted to write a networked poker game as a final project

in a class that I was teaching. I helped them with the network part of the

project by writing a basic framework to support communication between the players.

Since the application illustrates a variety of important ideas, I decided to

include a somewhat more advanced and general version of that framework in

this book. The final example in this section is a networked poker game.

12.5.1 The Netgame Framework

One can imagine playing many different games over the network. As far as the

network goes, all of those games have at least one thing in common: There has

to be some way for actions taken by one player to be communicated over the

network to other players. It makes good programming sense to make that

capability available in a reusable common core that can be used in many

different games. I have written such a core; it is defined by several

classes in the package netgame.common.

We have not done much with packages in this book, aside from using

built-in classes. Packages were introduced in Subsection 2.6.6,

but we have stuck to the “default package” in our programming examples.

In practice, however, packages are used in all but the simplest programming

projects to divide the code into groups of related classes. It makes particularly

good sense to define a reusable framework in a package that can be included as

a unit in a variety of projects.

Integrated development environments such as Eclipse make it very

easy to use packages: To use the netgame package in a project in an IDE, simply

copy-and-paste the entire netgame directory into the

project. Of course, since netgames use JavaFX, you need to use

an Eclipse project configured to support JavaFX, as discussed in

Section 2.6.

If you work on the command line, you should be in a working directory

that includes the netgame directory as a subdirectory.

You need to add JavaFX options to the javac

and java commands. Let’s say that you’ve defined

jfxc and jfx commands that are equivalent

to the javac and java with JavaFX options included, as discussed in

Subsection 2.6.7. Then, to compile

all the java files in the package netgame.common,

for example, you can use the following command in MacOS or Linux:

jfxc netgame/common/*.java

For Windows, you should use backslashes instead of forward slashes:

jfxc netgame\common\*.java

You will need similar commands to compile the source code for the examples in

this section, which are defined in other subpackages of netgame.

To run a main program that is defined in a package, you should again be in

a directory that contains the package as a subdirectory, and you should use the

full name of the class that you want to run. For example, the ChatRoomWindow

class, discussed later in this section, is defined in the package netgame.chat,

so you would run it with the command

jfx netgame.chat.ChatRoomWindow

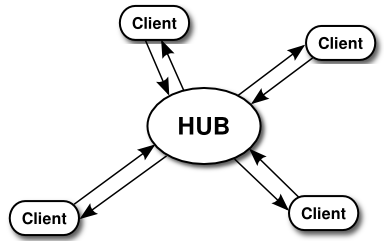

The applications discussed in this section are examples of distributed

computing, since they involve several computers communicating over a network.

Like the example in Subsection 12.4.5, they use a central “server,”

or “master,” to which a number of “clients” will connect. All communication

goes through the server; a client cannot send messages directly to another

client. In this section, I will refer to the server as a hub,

in the sense of “communications hub”:

The main things that you need to understand are that: The hub must be running

before any clients are started. Clients connect to the hub and can send messages to

the hub. The hub processes all messages from clients sequentially, in the order

in which they are received. The processing can result in the hub sending messages

out to one or more clients. Each client is identified by a unique ID number.

This is a framework that can be used in a variety of applications, and the

messages and processing will be defined by the particular application.

Here are some of the details…

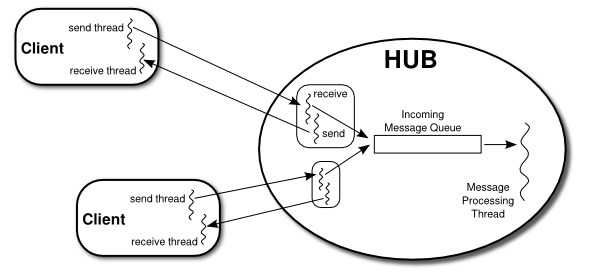

In Subsection 12.4.5,

messages were sent back and forth between the server and the client in a definite,

predetermined sequence. Communication between the server and a client

was actually communication between one thread running on the server and another

thread running on the client. For the netgame framework, however, I want to

allow for asynchronous communication, in which it is not possible to wait for

messages to arrive in a predictable sequence. To make this possible a netgame

client will use two threads for communication, one for sending messages to the hub and

one for receiving messages from the hub. Similarly, the netgame hub will use two threads

for communicating with each client.

The hub is generally connected to many clients and can receive messages

from any of those clients at any time. The hub will have to process each

message in some way. To organize this processing, the hub uses a single

thread to process all incoming messages. When a communication thread

receives a message from a client, it simply drops that message into a

queue of incoming messages. There is only one such queue, which is

used for messages from all clients. The message processing thread runs

in a loop in which it removes a message from the queue, processes it,

removes another message from the queue, processes it, and so on.

The queue itself is implemented as an object of type

LinkedBlockingQueue (see Subsection 12.3.3).

There is one more thread in the hub, not shown in the illustration. This final

thread creates a ServerSocket and uses it to listen

for connection requests from clients. Each time it accepts a connection request,

it hands off the client socket to another object, defined by the nested class

ConnectionToClient, which will handle communication with that client.

Each connected client is identified by an ID number. ID numbers 1, 2, 3, … are

assigned to clients as they connect. Since clients can also disconnect, the clients

connected at any give time might not have consecutive IDs. A variable

of type TreeMap<Integer,ConnectionToClient>

associates the ID numbers of connected clients with the objects that

handle their connections.

The messages that are sent and received are objects. The I/O streams

that are used for reading and writing objects are of type

ObjectInputStream and ObjectOutputStream.

(See Subsection 11.1.6.) The output stream of a socket is wrapped

in an ObjectOutputStream to make it possible to transmit

objects through that socket. The socket’s input stream is wrapped in

an ObjectInputStream to make it possible to receive

objects. Remember that the objects that are used with such streams

must implement the interface java.io.Serializable.

The netgame Hub class is defined in the file

Hub.java, in the

package netgame.common.

The port on which the server socket will listen must be specified as a

parameter to the Hub constructor.

The Hub class defines a method

protected void messageReceived(int playerID, Object message)

When a message from some client arrives at the front of the

queue of messages, the message-processing thread removes it

from the queue and calls this method. This is the point at which

the message from the client is actually processed.

The first parameter, playerID, is the ID number of the client

from whom the message was received, and the second parameter is the message

itself. In the Hub class, this method will simply

forward a copy of the message to every connected client. This defines the default processing

for incoming messages to the hub. To forward the message, it

wraps both the playerID and the message in

an object of type ForwardedMessage (defined in the

file ForwardedMessage.java,

in the package netgame.common). In a simple application such as

the chat room discussed in the next subsection,

this default processing might be exactly what is needed by the application.

For most applications, however, it will be necessary

to define a subclass of Hub and redefine

the messageReceived() method to do more complicated message processing.

There are several other methods in the Hub

class that you might want to redefine in a subclass, including

-

protected void playerConnected(int playerID) — This method is

called each time a player connects to the hub. The parameter playerID

is the ID number of the newly connected player. In the Hub

class, this method does nothing. (The hub has already sent a

StatusMessage to

every client to inform them about the new player; playerConnected()

is for any additional actions that a subclass of Hub

might want to take.) Note that the complete list of ID numbers

for currently connected players can be obtained by calling

getPlayerList(). -

protected void playerDisconnected(int playerID) — This

is called each time a player disconnects from the hub (after the hub sends a

StatusMessage to the clients). The parameter tells

which player has just disconnected. In the Hub class,

this method does nothing.

The Hub class also defines a number of useful public

methods, notably

-

sendToAll(message) — sends the specified message

to every client that is currently connected to the hub. The message must be a non-null

object that implements the Serializable interface. -

sendToOne(recipientID,message) — sends a

specified message to just one user. The first parameter,

recipientID is the ID number of the client who will receive the

message. This method returns a boolean value, which is false if

there is no connected client with the specified recipientID. -

shutDownServerSocket() — shuts down the hub’s

server socket, so that no additional clients will be able to connect. This could

be used, for example, in a two-person game, after the second client has connected. -

setAutoreset(autoreset) — sets the boolean

value of the autoreset property. If this property is true,

then the ObjectOutputStreams that are used to transmit

messages to clients will automatically be reset before each message is

transmitted. The default value is false.

(Resetting an ObjectOutputStream is something

that has to be done if an object is written to the stream, modified, and then

written to the stream again. If the stream is not reset before writing the

modified object, then the old, unmodified value is sent to the stream instead of the new value.

See Subsection 11.1.6 for a discussion of this technicality. The preferred solution

is to use only immutable objects for communication; in that case, no resetting is necessary.)

For more information—and to see how all this is implemented—you

should read the source code file Hub.java.

With some effort and study, you should be able to understand everything in that file.

(However, you only need to understand the public and protected interface of

Hub and other classes in the netgame framework

to write applications based on it.)

Turning to the client side, the basic netgame client class is defined in the file

Client.java, in

the package netgame.common.

The Client class has a constructor that specifies

the host name (or IP address) and port number of the hub to which the client will connect.

This constructor blocks until the connection has been established.

Client is an abstract class.

Every netgame application must define a subclass of Client

and provide a definition for the abstract method:

abstract protected void messageReceived(Object message);

This method is called each time a message is received from

the netgame hub. A subclass of client

might also override the protected methods

playerConnected, playerDisconnected,

serverShutdown, and connectionClosedByError.

See the source code

for more information. I should also note that Client

contains the protected instance variable connectedPlayerIDs,

of type int[], an array containing the ID numbers of all the clients

that are currently connected to the hub. The most important public

methods that are provided by the Client class are

-

send(message) — transmits a message to the hub. The

message can be any non-null object that implements the

Serializable interface. - getID() — gets the ID number that was assigned to this client by the hub.

-

disconnect() — closes the client’s connection to the hub.

It is not possible to send messages after disconnecting. The send()

method will throw an IllegalStateException if an attempt is

made to do so.

The Hub and Client classes

are meant to define a general framework that can be used as the basis for

a variety of networked games—and, indeed, of other distributed programs.

The low level details of network communication and multithreading are hidden

in the private sections of these classes. Applications that

build on these classes can work in terms of higher-level concepts such

as players and messages. The design of these classes was developed though several

iterations, based on experience with several actual applications. I urge

you to look at the source code to see how Hub and

Client use threads, sockets, and I/O streams. In the

remainder of this section, I will discuss three applications built on

the netgame framework. I will not discuss these applications in great detail.

You can find the complete source code for all three in the

netgame package.

12.5.2 A Simple Chat Room

Our first example is a “chat room,” a network application

where users can connect to a server and can then post messages

that will be seen by all current users of the room. It is similar

to the GUIChat program

from Subsection 12.4.2, except that any number of

users can participate in a chat. While this application is not

a game, it does show the basic functionality of the

netgame framework.

The chat room application consists of two programs. The first,

ChatRoomServer.java,

is a completely trivial program that simply creates a netgame

Hub to listen for connection requests

from netgame clients:

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

new Hub(PORT);

}

catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println("Can't create listening socket. Shutting down.");

}

}

The port number, PORT, is defined as a constant in the

program and is arbitrary, as long as both the server and the

clients use the same port. Note that

ChatRoom uses the Hub class itself, not a subclass.

The second part of the chat room application is the program

ChatRoomWindow.java,

which is meant to be run by users who want to participate in the chat room.

A potential user must know the name (or IP address) of the computer

where the hub is running. (For testing, it is possible to run

the client program on the same computer as the hub, using localhost

as the name of the computer where the hub is running.)

When ChatRoomWindow is

run, it uses a dialog box to ask the user for this information. It

then opens a window that will serve as the user’s interface to the chat

room. The window has a large transcript area that displays messages that

users post to the chat room. It also has a text input box where the

user can enter messages. When the user enters a message, that message

will be posted to the transcript of every user who is connected to the

hub, so all users see every message sent by every user. Let’s look

at some of the programming.

Any netgame application must define a subclass of the abstract

Client class.

For the chat room application, clients are defined by a nested

class ChatClient inside ChatRoomWindow.

The program has an instance variable, connection, of type

ChatClient, which represents the program’s

connection to the hub. When the user enters a message, that message

is sent to the hub by calling

connection.send(message);

When the hub receives the message, it packages it into an object

of type ForwardedMessage,

along with the ID number of the client who sent the message. The hub

sends a copy of that ForwardedMessage to every

connected client, including the client who sent the message. On the client

side in each client, when the message is received from the hub,

the messageReceived() method of the ChatClient

object in that client is called.

ChatClient overrides this method to program it to

add the message to the transcript of the ChatClientWindow.

To summarize: Every message entered by any user is sent to the hub, which

just sends out copies of each message that it receives to every client. Each

client will see exactly the same stream of messages from the hub.

A client is also notified when a player connects to or disconnects from

the hub and when the connection with the hub is lost. ChatClient

overrides the methods that are called when these events happen so that

they post appropriate messages to the transcript. Here’s the complete definition

of the client class for the chat room application:

/**

* A ChatClient connects to the Hub and is used to send messages to

* the Hub and receive messages from the Hub. Messages received from

* the Hub will be of type ForwardedMessage and will contain the

* ID number of the sender and the string that was sent by

* that user.

*/

private class ChatClient extends Client {

/**

* Opens a connection to the chat room server on a specified computer.

*/

ChatClient(String host) throws IOException {

super(host, PORT);

}

/**

* Responds when a message is received from the server. It should be

* a ForwardedMessage representing something that one of the participants

* in the chat room is saying. The message is simply added to the

* transcript, along with the ID number of the sender.

*/

protected void messageReceived(Object message) {

if (message instanceof ForwardedMessage) {

// (no other message types are expected)

ForwardedMessage bm = (ForwardedMessage)message;

addToTranscript("#" + bm.senderID + " SAYS: " + bm.message);

}

}

/**

* Called when the connection to the client is shut down because of some

* error message. (This will happen if the server program is terminated.)

*/

protected void connectionClosedByError(String message) {

addToTranscript(

"Sorry, communication has shut down due to an error:\n "

+ message );

Platform.runLater( () -> {

sendButton.setDisable(true);

messageInput.setEditable(false);

messageInput.setDisable(true);

messageInput.setText("");

});

connected = false;

connection = null;

}

/**

* Posts a message to the transcript when someone joins the chat room.

*/

protected void playerConnected(int newPlayerID) {

addToTranscript(

"Someone new has joined the chat room, with ID number "

+ newPlayerID );

}

/**

* Posts a message to the transcript when someone leaves the chat room.

*/

protected void playerDisconnected(int departingPlayerID) {

addToTranscript( "The person with ID number "

+ departingPlayerID + " has left the chat room");

}

} // end nested class ChatClient

Except for the constructor, none of the methods in the ChatClient

class are called by the ChatRoomWindow program; they are called from

the connection-handling thread in the client object, which was programmed in

Client.java.

For the full source code of the chat room application, see the

source code files, which can be found in the package

netgame.chat.

Note: A user of my chat room application is identified only by an ID number that

is assigned by the hub when the client connects. Essentially, users are

anonymous, which is not very satisfying. See Exercise 12.7

at the end of this chapter for a way of addressing this issue.

12.5.3 A Networked TicTacToe Game

My second example is a very simple game: the familiar children’s game

TicTacToe. In TicTacToe, two players alternate placing marks on a

three-by-three board. One player plays X’s; the other plays O’s.

The object is to get three X’s or three O’s in a row.

At a given time, the state of a TicTacToe game consists of

various pieces of information such as the current contents of

the board, whose turn it is, and—when the game is over—who

won or lost. In a typical non-networked version of the game,

this state would be represented by instance variables. The

program would consult those instance variables to determine

how to draw the board and how to respond to user actions such

as mouse clicks. In the networked netgame version, however,

there are three objects involved: Two objects belonging to a

client class, which provide the interface to the two players

of the game, and the hub object that manages the connections to the

clients. These objects are not even on the same

computer, so they certainly can’t use the same state variables!

Nevertheless, the game has to have a single, well-defined

state at any time, and both players have to be aware of

that state.

My solution for TicTacToe is to store the “official” game state in

the hub, and to send a copy of that state to each player

every time the state changes. The players can’t change

the state directly. When a player takes some action, such

as placing a piece on the board, that action is sent

as a message to the hub. The hub changes the state to

reflect the result of the action, and it sends the new

state to both players. The window used by each player will

then be updated to reflect the new state. In this way, we

can be sure that the game always looks the same to both players.

(Instead of sending a complete copy of the state each time the state

changes, I might have sent just the change. But that would require

some way to encode the changes into messages that can be sent

over the network. Since the state is so simple, it seemed easier

just to send the entire state as the message in this case.)

Networked TicTacToe is defined in several classes in the

package netgame.tictactoe. The class

TicTacToeGameState

represents the state of a game. It includes a method

public void applyMessage(int senderID, Object message)

that modifies the state of the game to reflect the effect of a message

received from one of the players of the game. The message will

represent some action taken by the player, such as clicking

on the board.

The basic Hub class knows nothing about TicTacToe.

Since the hub for the TicTacToe game has to keep track of the state

of the game, it has to be defined by a subclass of Hub.

The TicTacToeGameHub

class is quite simple. It overrides the messageReceived() method

so that it responds to a message from a player by applying that message

to the game state and sending a copy of the new state to both players. It

also overrides the playerConnected() and playerDisconnected()

methods to take appropriate actions, since the game can only be played when

there are exactly two connected players. Here is the complete source code:

package netgame.tictactoe;

import java.io.IOException;

import netgame.common.Hub;

/**

* A "Hub" for the network TicTacToe game. There is only one Hub

* for a game, and both network players connect to the same Hub.

* Official information about the state of the game is maintained

* on the Hub. When the state changes, the Hub sends the new

* state to both players, ensuring that both players see the

* same state.

*/

public class TicTacToeGameHub extends Hub {

private TicTacToeGameState state; // Records the state of the game.

/**

* Create a hub, listening on the specified port. Note that this

* method calls setAutoreset(true), which will cause the output stream

* to each client to be reset before sending each message. This is

* essential since the same state object will be transmitted over and

* over, with changes between each transmission.

* @param port the port number on which the hub will listen.

* @throws IOException if a listener cannot be opened on the specified port.

*/

public TicTacToeGameHub(int port) throws IOException {

super(port);

state = new TicTacToeGameState();

setAutoreset(true);

}

/**

* Responds when a message is received from a client. In this case,

* the message is applied to the game state, by calling state.applyMessage().

* Then the possibly changed state is transmitted to all connected players.

*/

protected void messageReceived(int playerID, Object message) {

state.applyMessage(playerID, message);

sendToAll(state);

}

/**

* This method is called when a player connects. If that player

* is the second player, then the server's listening socket is

* shut down (because only two players are allowed), the

* first game is started, and the new state -- with the game

* now in progress -- is transmitted to both players.

*/

protected void playerConnected(int playerID) {

if (getPlayerList().length == 2) {

shutdownServerSocket();

state.startFirstGame();

sendToAll(state);

}

}

/**

* This method is called when a player disconnects. This will

* end the game and cause the other player to shut down as

* well. This is accomplished by setting state.playerDisconnected

* to true and sending the new state to the remaining player, if

* there is one, to notify that player that the game is over.

*/

protected void playerDisconnected(int playerID) {

state.playerDisconnected = true;

sendToAll(state);

}

}

A player’s interface to the game is represented by the

class TicTacToeWindow.

As in the chat room application, this class defines a nested subclass

of Client to represent the client’s connection

to the hub. When the state of the game changes, a message is sent

to each client, and the client’s messageReceived() method

is called to process that message. That method, in turn, calls a

newState() method in the TicTacToeWindow

class to update the window. That method is called on the JavaFX

application thread using Platform.runLater():

protected void messageReceived(Object message) {

if (message instanceof TicTacToeGameState) {

Platform.runLater( () -> newState( (TicTacToeGameState)message ) );

}

}

To run the TicTacToe netgame, the two players should each run the program

Main.java

in the package netgame.tictactoe.

This program presents the user with a window where the user can

choose to start a new game or to join an existing game. If the user

starts a new game, then a TicTacToeHub is created

to manage the game, and a second window of type TicTacToeWindow is opened

that immediately connects to the hub. The game will start as soon as a second

player connects to the hub. On the other hand, if the user running

Main chooses to connect to an existing

game, then no hub is created. A TicTacToeWindow is created,

and that window connects to the

hub that was created by the first player. The second player has to know

the name of the computer where the first player’s program is running.

As usual, for testing, you can run everything on one computer and use

“localhost” as the computer name.

(This is the first program that we have seen that uses two different windows.

Note that TicTacToeWindow is defined as a subclass of

Stage, the JavaFX class that represents windows.

A JavaFX program starts with a “primary stage” that is created by the system

and passed as a parameter to the start() method. But an application

can certainly create additional windows.)

12.5.4 A Networked Poker Game

And finally, we turn very briefly to the application that inspired the

netgame framework: Poker. In particular, I have implemented a

two-player version of the traditional “five card draw” version of

that game. This is a rather complex application, and I do not

intend to say much about it here other than to describe the general

design. The full source code can be found in the package

netgame.fivecarddraw.

To fully understand it, you will need to be familiar with the

game of five card draw poker.

In general outline, the Poker game is similar to the TicTacToe game.

There is a Main

class that is run by both players. The first player starts a new game; the second

must join that existing game. There is a class

PokerGameState

to represent the state of a game. And there is a subclass,

PokerHub,

of Hub to manage the game.

But Poker is a much more complicated game than TicTacToe, and the

game state is correspondingly more complicated. It’s not clear that we

want to broadcast a new copy of the complete game state to the players

every time some minor change is made in the state. Furthermore, it

doesn’t really make sense for both players to know the full game state—that

would include the opponent’s hand and full knowledge of the deck from which

the cards are dealt. (Of course, our client programs wouldn’t have to show

the full state to the players, but it would be easy enough for a player to

substitute their own client program to enable cheating.) So in the Poker

application, the full game state is known only to the PokerHub.

A PokerGameState object represents a view of the

game from the point of view of one player only. When the state of the game

changes, the PokerHub creates two different

PokerGameState objects, representing the state of the

game from each player’s point of view, and it sends the appropriate game state

object to each player. You can see the source code

for details.

(One of the hard parts in poker is to implement some way to compare

two hands, to see which is higher. In my game, this is handled by the

class PokerRank.

You might find this class useful in other poker games.)