8 Javanotes 9.0, Section 5.7 — Interfaces

Section 5.7

Interfaces

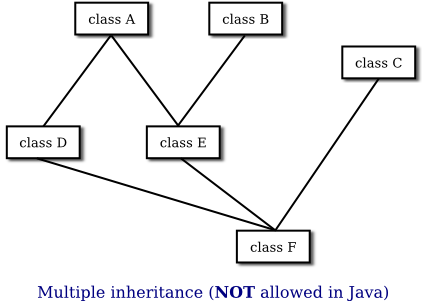

Some object-oriented programming languages, such as C++, allow a class to

extend two or more superclasses. This is called multiple inheritance.

In the illustration below, for example, class E is shown as

having both class A and class B as direct superclasses, while class F has three

direct superclasses.

Such multiple inheritance is not allowed in Java. The

designers of Java wanted to keep the language reasonably simple, and felt that

the benefits of multiple inheritance were not worth the cost in increased

complexity. However, Java does have a feature that can be used to accomplish

many of the same goals as multiple inheritance: interfaces.

We have already encountered “functional interfaces” in Section 4.5

in connection with lambda expressions. A functional interface specifies

a single method. However, interfaces can be much more complicated than

that, and they have many other uses.

You are not likely to need to write your own interfaces until you get to the

point of writing fairly complex programs. However, there are several interfaces

that are used in important ways in Java’s standard packages, and you will need

to learn how to use them.

5.7.1 Defining and Implementing Interfaces

We encountered the term “interface” in other contexts, in connection with black

boxes in general and subroutines in particular. The interface of a subroutine

consists of the name of the subroutine, its return type, and the number and

types of its parameters. This is the information you need to know if you want

to call the subroutine. A subroutine also has an implementation: the block of

code which defines it and which is executed when the subroutine is called.

In Java, interface is a reserved word with an additional, technical

meaning. An “interface” in this sense consists of a set of instance method

interfaces, without any associated implementations. (Actually, a Java interface

can contain other things as well, as we’ll see later.)

A class can implement

an interface by providing an implementation

for each of the methods specified by the interface. Here is an example of a

very simple Java interface:

public interface Strokeable {

public void stroke(GraphicsContext g);

}

This looks much like a class definition, except that the implementation of

the stroke() method is omitted. A class that implements the

interface Strokeable must provide an implementation for

stroke(). Of course, the class can also include other methods and variables. For

example,

public class Line implements Strokeable {

public void stroke(GraphicsContext g) {

. . . // do something—presumably, draw a line

}

. . . // other methods, variables, and constructors

}

Note that to implement an interface, a class must do more than simply provide

an implementation for each method in the interface; it must also state that

it implements the interface, using the reserved word implements as

in this example: “public class Line implements Strokeable“.

Any concrete class that implements the Strokeable interface must define a

stroke() instance method. Any object created from such a class includes

a stroke() method. We say that an object implements an

interface if it belongs to a class that implements the interface. For

example, any object of type Line implements the Strokeable

interface.

While a class can extend only one other class, it can

implement any number of interfaces. In fact, a class can both extend

one other class and implement one or more interfaces. So, we can have things

like

class FilledCircle extends Circle

implements Strokeable, Fillable {

. . .

}

The point of all this is that, although interfaces are not classes, they are

something very similar. An interface is very much like an abstract class, that

is, a class that can never be used for constructing objects, but can be used as

a basis for making subclasses. The subroutines in an interface are abstract

methods, which must be implemented in any concrete class that implements the

interface. You can compare the Strokeable

interface with the abstract class

public abstract class AbstractStrokeable {

public abstract void stroke(GraphicsContext g);

}

The main difference is that a class that extends AbstractStrokeable

cannot extend any other class, while a class that implements Strokeable

can also extend some class, as well as implement other interfaces. Of course, an

abstract class can contain non-abstract methods as well as abstract methods.

An interface is like a “pure” abstract class, which contains only abstract methods.

Note that the methods declared in an interface must be public and abstract. In fact,

since that is the only option, it is not necessary to specify either of these modifiers in

the declaration.

In addition to method declarations, an interface can also include variable

declarations. The variables must be “public static final”

and effectively become public static final variables in every class that implements

the interface. In fact, since the variables can only be public and static and final,

specifying the modifiers is optional. For example,

public interface ConversionFactors {

int INCHES_PER_FOOT = 12;

int FEET_PER_YARD = 3;

int YARDS_PER_MILE = 1760;

}

This is a convenient way to define named constants that can be

used in several classes. A class that implements ConversionFactors

can use the constants defined in the interface as if they were defined in the

class.

Note in particular that any variable that is defined in an interface is

a constant. It’s not really a variable at all. An interface cannot add

instance variables to the classes that implement it.

An interface can extend one or more other interfaces. For example, if

Strokeable is the interface given above and Fillable

is an interface that defines a method fill(g), then we could define

public interface Drawable extends Strokeable, Fillable {

// (more methods/constants could be defined here)

}

A concrete class that implements Drawable must then

provide implementations for the stroke() method from

Strokeable and the fill() method from

Fillable, as well as for any abstract methods specified

directly in the Drawable interface.

An interface is usually defined in its own .java file, whose

name must match the name of the interface. For example,

Strokeable would be defined in a file named

Strokeable.java. Just like a class, an

interface can be in a package and can import

things from other packages.

This discussion has been about the syntax rules for interfaces.

But of course, an interface also has a semantic component. That is,

the person who creates the interface intends for the methods that

it defines to have some specific meaning. The interface definition

should include comments to express that meaning, and classes that implement the

interface should take that meaning into account. The Java compiler,

however, can only check the syntax; it can’t enforce the meaning. For example,

the stroke() method in an object that implements Strokeable

is presumably meant to draw a graphical representation of the object by

stroking it,

but the compiler can only check that the stroke() method exists

in the object.

5.7.2 Default Methods

Starting in Java 8, interfaces can contain default methods.

Unlike the usual abstract methods in interfaces, a default method has an implementation. When a class

implements the interface, it does not have to provide an implementation for the

default method—although it can do so if it wants to provide a different implementation.

Essentially, default methods are inherited from interfaces in much the same way that

ordinary methods are inherited from classes. This moves Java partway towards supporting

multiple inheritance. It’s not true multiple inheritance, however, since interfaces

still cannot define instance variables. Default methods can call abstract methods that

are defined in the same interface, but they cannot refer to any instance variables.

Note that a functional interface can include default methods in addition to

the single abstract method that it specifies.

A default method in an interface must be marked with the modifier default.

It can optionally be marked public but, as for everything else in interfaces,

default methods are automatically public and the public modifier can be omitted.

Here is an example:

public interface Readable { // represents a source of input

public char readChar(); // read the next character from the input

default public String readLine() { // read up to the next line feed

StringBuilder line = new StringBuilder();

char ch = readChar();

while (ch != '\n') {

line.append(ch);

ch = readChar();

}

return line.toString();

}

}

A concrete class that implements this interface must provide an implementation for

readChar(). It will inherit a definition for readLine() from the interface,

but can provide a new definition if necessary. When a class includes an implementation

for a default method, the implementation given in the class overrides the

default method from the interface.

Note that the default

readLine() calls the abstract method readChar(),

whose definition will only be provided in an implementing class. The reference

to readChar() in the definition is polymorphic.

The default implementation of readLine() is one that would make

sense in almost any class that implements Readable. Here’s

a rather silly example of a class that implements Readable,

including a main() routine that tests the class. Can you figure out

what it does?

public class Stars implements Readable {

public char readChar() {

if (Math.random() > 0.02)

return '*';

else

return '\n';

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

Stars stars = new Stars();

for (int i = 0 ; i < 10; i++ ) {

String line = stars.readLine(); // Calls the default method!

System.out.println( line );

}

}

}

Default methods provide Java with a capability similar to something called

a “mixin” in other programming languages, namely the ability to mix functionality from

another source into a class. Since a class can implement several interfaces,

it is possible to mix in functionality from several different sources.

5.7.3 Interfaces as Types

As with abstract classes, even though you can’t construct an

object from an interface, you can declare a variable whose type is given by the

interface. For example, if Strokeable is the interface given above, and if

Line and Circle are classes that implement

Strokeable, as above, then you could say:

Strokeable figure; // Declare a variable of type Strokeable. It

// can refer to any object that implements the

// Strokeable interface.

figure = new Line(); // figure now refers to an object of class Line

figure.stroke(g); // calls stroke() method from class Line

figure = new Circle(); // Now, figure refers to an object

// of class Circle.

figure.stroke(g); // calls stroke() method from class Circle

A variable of type Strokeable can refer to any object of any class

that implements the Strokeable interface. A statement like

figure.stroke(g), above, is legal because figure is of type

Strokeable, and any

Strokeable object has a stroke()

method. So, whatever object figure refers to, that object must

have a stroke() method.

Note that a type is something that can be used

to declare variables. A type can also be used to specify the type of a

parameter in a subroutine, or the return type of a function. In Java, a type

can be either a class, an interface, or one of the eight built-in primitive

types. These are the only possibilities (given a few special cases, such

as an enum, which is considered to be a special kind of class).

Of these, however, only classes can be used to construct new objects.

An interface can also be the base type of an array. For example, we can

use an array type Strokeable[] to declare

variables and create arrays. The elements

of the array can refer to any objects that implement the Strokeable

interface:

Strokeable[] listOfFigures; listOfFigures = new Strokeable[10]; listOfFigures[0] = new Line(); listOfFigures[1] = new Circle(); listOfFigures[2] = new Line(); . . .

Every element of the array will then have a stroke() method, so that

we can say things like listOfFigures[i].stroke(g).