35 Javanotes 9.0, Section 8.5 — Analysis of Algorithms

Section 8.5

Analysis of Algorithms

This chapter has concentrated mostly on

correctness of programs. In practice, another issue

is also important: efficiency. When analyzing a

program in terms of efficiency, we want to look at questions such

as, “How long does it take for the program to run?” and “Is there

another approach that will get the answer more quickly?”

Efficiency will always be less important than correctness; if you

don’t care whether a program works correctly, you can make it run

very quickly indeed, but no one will think it’s much of an

achievement! On the other hand, a program that gives a correct

answer after ten thousand years isn’t very useful either, so

efficiency is often an important issue.

The term “efficiency” can refer to efficient use of almost any

resource, including time, computer memory, disk space, or network

bandwidth. In this section, however, we will deal exclusively with

time efficiency, and the major question that we want to ask about

a program is, how long does it take to perform its task?

It really makes little sense to classify an individual program

as being “efficient” or “inefficient.” It makes more sense to

compare two (correct) programs that perform the same task and ask

which one of the two is “more efficient,” that is, which one

performs the task more quickly. However, even here there are

difficulties. The running time of a program is not well-defined.

The run time can be different depending on the number and speed of the

processors in the computer on which it is run and, in the case of Java,

on the design of the Java Virtual Machine which is used to interpret

the program. It can depend on details of the compiler which is

used to translate the program from high-level language to machine

language. Furthermore, the run time of a program depends on

the size of the problem which the program has to solve. It takes

a sorting program longer to sort 10000 items than it takes it

to sort 100 items. When the run times of two programs are

compared, it often happens that Program A solves small problems

faster than Program B, while Program B solves large problems

faster than Program A, so that it is simply not the case that one

program is faster than the other in all cases.

In spite of these difficulties, there is a field of computer science

dedicated to analyzing the efficiency of programs. The field is

known as Analysis of Algorithms. The focus is

on algorithms, rather than on programs as such, to avoid having

to deal with multiple implementations of the same algorithm written

in different languages, compiled with different compilers, and running

on different computers. Analysis of Algorithms is a mathematical

field that abstracts away from these down-and-dirty details.

Still, even though it is a theoretical field, every working programmer

should be aware of some of its techniques and results. This section

is a very brief introduction to some of those techniques and results.

Because this is not a mathematics book, the treatment will be

rather informal.

One of the main techniques of analysis of algorithms is

asymptotic analysis. The term “asymptotic”

here means basically “the tendency in the long run, as the size of

the input is increased.” An asymptotic

analysis of an algorithm’s run time looks at the question of how

the run time depends on the size of the problem. The analysis is

asymptotic because it only considers what happens to the run time

as the size of the problem increases without limit; it is not

concerned with what happens for problems of small size or, in fact,

for problems of any fixed finite size. Only what happens in the

long run, as the problem size increases without limit, is important.

Showing that Algorithm A is asymptotically faster than

Algorithm B doesn’t necessarily mean that Algorithm A will

run faster than Algorithm B for problems of size 10 or size

1000 or even size 1000000—it only means that if you keep

increasing the problem size, you will eventually come to a point

where Algorithm A is faster than Algorithm B. An asymptotic

analysis is only a first approximation, but in practice it often

gives important and useful information.

Central to asymptotic analysis is Big-Oh notation.

Using this notation, we might say, for example, that an algorithm has a running time

that is O(n2) or O(n) or O(log(n)). These notations

are read “Big-Oh of n squared,” “Big-Oh of n,” and “Big-Oh of log n”

(where log is a logarithm function). More generally, we can refer to

O(f(n)) (“Big-Oh of f of n”), where f(n) is some function that

assigns a positive real number to every positive integer n. The “n”

in this notation refers to the size of the problem. Before you can even

begin an asymptotic analysis, you need some way to measure problem size.

Usually, this is not a big issue. For example, if the problem is to

sort a list of items, then the problem size can be taken to be the number of

items in the list. When the input to an algorithm is an integer, as in

the case of an algorithm that checks whether a given positive integer is prime,

the usual measure of the size of a problem is the number of bits in the

input integer rather than the integer itself. More generally, the number

of bits in the input to a problem is often a good measure of the size

of the problem.

To say that the running time of an algorithm is O(f(n)) means that

for large values of the problem size, n, the running time of the algorithm

is no bigger than some constant times f(n). (More rigorously, there is a

number C and a positive integer M such that whenever n is greater than M,

the run time is less than or equal to C*f(n).) The constant takes into

account details such as the speed of the computer on which the algorithm

is run; if you use a slower computer, you might have to use a bigger constant

in the formula, but changing the constant won’t change the basic fact that the

run time is O(f(n)). The constant also makes it unnecessary to say

whether we are measuring time in seconds, years, CPU cycles, or any other

unit of measure; a change from one unit of measure to another is just

multiplication by a constant. Note also that O(f(n)) doesn’t depend at

all on what happens for small problem sizes, only on what happens in the

long run as the problem size increases without limit.

To look at a simple example, consider the problem of adding up all

the numbers in an array. The problem size, n, is the length of the array.

Using A as the name of the array, the algorithm can be expressed in Java as:

total = 0; for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) total = total + A[i];

This algorithm performs the same operation, total = total + A[i],

n times. The total time spent on this operation is a*n, where a is the

time it takes to perform the operation once. Now, this is not the only thing

that is done in the algorithm. The value of i is incremented and

is compared to n each time through the loop. This adds an additional

time of b*n to the run time, for some constant b. Furthermore, i and

total both have to be initialized to zero; this adds some constant

amount c to the running time. The exact running time would then be

(a+b)*n+c, where the constants a, b, and c depend on factors such as how the

code is compiled and what computer it is run on. Using the fact that c is less than

or equal to c*n for any positive integer n, we can say that the run time

is less than or equal to (a+b+c)*n. That is, the run time is less than or equal

to a constant times n. By definition, this means that the run time for this

algorithm is O(n).

If this explanation is too mathematical for you, we can just note that for large

values of n, the c in the formula (a+b)*n+c is insignificant compared to the other

term, (a+b)*n. We say that c is a “lower order term.” When doing asymptotic analysis,

lower order terms can be discarded. A rough, but correct, asymptotic analysis of

the algorithm would go something like this: Each iteration of the for

loop takes a certain constant amount of time. There are n iterations of the loop,

so the total run time is a constant times n, plus lower order terms (to account

for the initialization). Disregarding lower order terms, we see that the

run time is O(n).

Note that to say that an algorithm has run time O(f(n)) is to say that its

run time is no bigger than some constant times f(n) (for large values of n). O(f(n)) puts

an upper limit on the run time. However, the run time could be smaller,

even much smaller. For example, if the run time is O(n), it would also be

correct to say that the run time is O(n2) or even O(n10).

If the run time is less than a constant times n, then it is certainly less than the

same constant times n2 or n10.

Of course, sometimes it’s useful to have a lower limit on the run time.

That is, we want to be able to say that the run time is greater than or equal to

some constant times f(n) (for large values of n). The notation for this

is Ω(f(n)), read “Omega of f of n” or “Big Omega of f of n.”

“Omega” is the name of a letter

in the Greek alphabet, and Ω is the upper case version of that letter.

(To be technical, saying that the run time of an algorithm is Ω(f(n)) means that

there is a positive number C and a positive integer M such that whenever n is greater than M,

the run time is greater than or equal to C*f(n).) O(f(n)) tells you something

about the maximum amount of time that you might have to wait for an algorithm to

finish; Ω(f(n)) tells you something about the minimum time.

The algorithm for adding up the numbers in an array has a run time that

is Ω(n) as well as O(n). When an algorithm has a run time that is

both Ω(f(n)) and O(f(n)), its run time is said to be Θ(f(n)),

read “Theta of f of n” or “Big Theta of f of n.”

(Theta is another letter from the Greek alphabet.)

To say that the run time of an algorithm is Θ(f(n)) means that for large

values of n, the run time is between a*f(n) and b*f(n), where a and b are constants

(with b greater than a, and both greater than 0).

Let’s look at another example. Consider the algorithm that can be expressed in Java

in the following method:

/**

* Sorts the n array elements A[0], A[1], ..., A[n-1] into increasing order.

*/

public static void simpleBubbleSort( int[] A, int n ) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

// Do n passes through the array...

for (int j = 0; j < n-1; j++) {

if ( A[j] > A[j+1] ) {

// A[j] and A[j+1] are out of order, so swap them

int temp = A[j];

A[j] = A[j+1];

A[j+1] = temp;

}

}

}

}

Here, the parameter n represents the problem size. The outer for

loop in the method is executed n times. Each time the outer for loop

is executed, the inner for loop is executed n-1 times, so the if

statement is executed n*(n-1) times. This is n2-n, but since lower order

terms are not significant in an asymptotic analysis, it’s good enough to say that

the if statement is executed about n2 times. In particular,

the test A[j] > A[j+1] is executed about n2 times,

and this fact by itself is enough to say that the run time of the algorithm is

Ω(n2), that is, the run time is at least some constant times

n2. Furthermore, if we look at other operations—the assignment

statements, incrementing i and j, etc.—none

of them are executed more than n2 times, so the run time is also

O(n2), that is, the run time is no more than some constant

times n2. Since it is both Ω(n2) and O(n2),

the run time of the simpleBubbleSort algorithm is Θ(n2).

You should be aware that some people use the notation O(f(n)) as if

it meant Θ(f(n)). That is, when they say that the run time of an algorithm

is O(f(n)), they mean to say that the run time is about equal to

a constant times f(n). For that, they should use Θ(f(n)). Properly

speaking, O(f(n)) means that the run time is less than a constant times

f(n), possibly much less.

So far, my analysis has ignored an important detail. We have looked at how run time

depends on the problem size, but in fact the run time usually depends not just on the

size of the problem but on the specific data that has to be processed. For example, the

run time of a sorting algorithm can depend on the initial order of the items that are

to be sorted, and not just on the number of items.

To account for this dependency, we can consider either the

worst case run time analysis or the

average case run time analysis of an algorithm.

For a worst case run time analysis, we consider all possible problems of size n

and look at the longest possible run time for all such problems.

For an average case analysis, we consider all possible problems of size n

and look at the average of the run times for all such problems.

Usually, the average case analysis assumes that all problems of size n

are equally likely to be encountered, although this is not always realistic—or

even possible in the case where there is an infinite number of different

problems of a given size.

In many cases, the average and the worst case run times are the same to within a

constant multiple. This means that as far as asymptotic analysis is concerned, they

are the same. That is, if the average case run time is O(f(n)) or Θ(f(n)), then

so is the worst case. However, later in the book, we will encounter a few cases where

the average and worst case asymptotic analyses differ.

It is also possible to talk about best case run time

analysis, which looks at the shortest possible run time for all inputs

of a given size. However, a best case analysis is only occasionally useful.

So, what do you really have to know about analysis of algorithms to read the rest

of this book? We will not do any rigorous mathematical analysis, but you should be

able to follow informal discussion of simple cases such as the examples that we

have looked at in this section. Most important, though, you should have a feeling

for exactly what it means to say that the running time of an algorithm is

O(f(n)) or Θ(f(n)) for some common functions f(n). The main point is

that these notations do not tell you anything about the actual numerical value of

the running time of the algorithm for any particular case. They do not tell you

anything at all about the running time for small values of n. What they do tell

you is something about the rate of growth of the running time

as the size of the problem increases.

Suppose you compare two algorithms that solve the same problem. The run time of

one algorithm is Θ(n2), while the run time of the second algorithm

is Θ(n3). What does this tell you? If you want to know which

algorithm will be faster for some particular problem of size, say, 100, nothing

is certain. As far as you can tell just from the asymptotic analysis, either algorithm

could be faster for that particular case—or in any particular case.

But what you can say for sure is that if you look at larger and larger

problems, you will come to a point where the Θ(n2) algorithm

is faster than the Θ(n3) algorithm. Furthermore, as you continue

to increase the problem size, the relative advantage of the Θ(n2)

algorithm will continue to grow. There will be values of n for which the

Θ(n2) algorithm is a thousand times faster, a million times

faster, a billion times faster, and so on. This is because for any positive

constants a and b, the function a*n3 grows faster than

the function b*n2 as n gets larger. (Mathematically, the limit of the ratio

of a*n3 to b*n2 is infinite as n approaches infinity.)

This means that for “large” problems, a Θ(n2) algorithm will

definitely be faster than a Θ(n3) algorithm. You just don’t

know—based on the asymptotic analysis alone—exactly how large “large” has

to be. In practice, in fact, it is likely that the Θ(n2)

algorithm will be faster even for fairly small values of n, and absent other

information you would generally prefer a Θ(n2) algorithm

to a Θ(n3) algorithm.

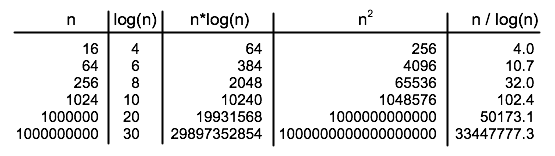

So, to understand and apply asymptotic analysis, it is essential to have some

idea of the rates of growth of some common functions. For the power functions

n, n2, n3, n4, …, the larger the

exponent, the greater the rate of growth of the function. Exponential functions

such as 2n and 10n, where the n is in the exponent, have

a growth rate that is faster than that of any power function. In fact,

exponential functions grow so quickly that an algorithm whose run time grows

exponentially is almost certainly impractical even for relatively modest

values of n, because the running time is just too long. Another function that

often turns up in asymptotic analysis is the logarithm function, log(n).

There are actually many different logarithm functions, but the one that

is usually used in computer science is the so-called logarithm to the

base two, which is defined by the fact that log(2x) = x for

any number x. (Usually, this function is written log2(n),

but I will leave out the subscript 2, since I will only use the base-two logarithm

in this book.) The logarithm function grows very slowly. The growth

rate of log(n) is much smaller than the growth rate of n. The growth rate

of n*log(n) is a little larger than the growth rate of n, but much smaller

than the growth rate of n2. The following table should help you

understand the differences among the rates of growth of various functions:

The reason that log(n) shows up so often is because of its association

with multiplying and dividing by two: Suppose you start with the number

n and divide it by 2, then divide by 2 again, and so on, until you get

a number that is less than or equal to 1. Then the number of divisions

is equal (to the nearest integer) to log(n).

As an example, consider the binary search algorithm from Subsection 7.5.1.

This algorithm searches for an item in a sorted array. The problem size, n, can be

taken to be the length of the array. Each step in the binary search algorithm

divides the number of items still under consideration by 2, and the algorithm

stops when the number of items under consideration is less than or equal to 1

(or sooner). It follows that the number of steps for an array of length n

is at most log(n). This means that the worst-case run time for binary search

is Θ(log(n)). (The average case run time is also Θ(log(n)).)

By comparison, the linear search algorithm, which was also presented in

Subsection 7.5.1 has a run time that is Θ(n).

The Θ notation gives us a quantitative way to express and to understand

the fact that binary search is “much faster” than linear search.

In binary search, each step of the algorithm divides the problem size by 2.

It often happens that some operation in an algorithm (not necessarily a single step)

divides the problem size by 2. Whenever that happens, the logarithm function

is likely to show up in an asymptotic analysis of the run time of the

algorithm.

Analysis of Algorithms is a large, fascinating field. We will only use

a few of the most basic ideas from this field, but even those can be very helpful

for understanding the differences among algorithms.